Continuity and Diversity: The Art of Arthur Amiotte – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Summer 2002

Continuity and Diversity: The Art of Arthur Amiotte

By Emma I. Hansen

Curator Emerita, Plains Indian Museum

Note: In 2002, the Buffalo Bill [Center of the West] hosted a special exhibition titled The Arthur Amiotte Retrospective: Continuity and Diversity, then the most comprehensive exhibition to date of the work of the internationally noted Lakota artist. Beginning with his early work as a young student of the Yanktonai Dakota painter Oscar Howe, and following his personal journey as an artist, scholar, writer, and educator, the exhibition included paintings, textile and fiber art, and collages produced from 1965 to 1999. The exhibition was a joint project of the Akta Lakota Museum at St. Joseph’s Indian School, The Heritage Center at Red Cloud Indian School, the Journey Museum, Northern Galleries at Northern State University, The University Art Galleries at the University of South Dakota, and The Visual Arts Center at the Washington Pavilion.

Below is an excerpt from a Points West article published at the time of the exhibition.

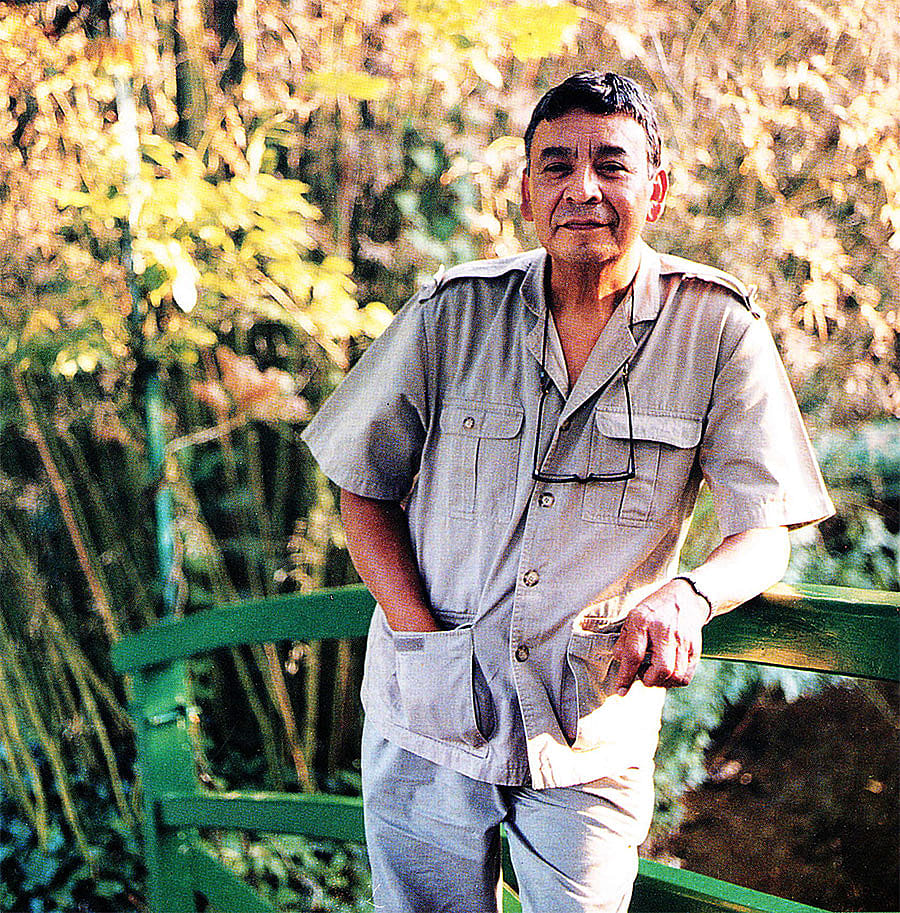

Born in 1942 on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota, Arthur Amiotte earned a Bachelor of Science degree in art education and a Master’s of Interdisciplinary studies in Anthropology, Religion, and Art. He has also received three honorary doctorates. As an educator, he has taught all aspects of Native traditional and contemporary studio fine arts. As a scholar, he has numerous publications on Native art and culture and has lectured throughout the United States and Europe. He has earned numerous awards including an Arts International Lila Wallace Readers Digest Artists at Giverny Fellowship, a Getty Foundation Grant, a Bush Leadership Fellowship, the South Dakota Governor’s Award for Outstanding Creative Achievement in the Arts, and the Lifetime Achievement Award as Artist and Scholar from the Native American Art Studies Association. As a Lakota traditionalist, he was mentored by his grandmother Christina Standing Bear and respected Oglala spiritual leader, Pete Catches, Sr. in artistic techniques and sacred ceremonies.

Arthur Amiotte is a founding member of the Plains Indian Museum Advisory Board, which guided the design and first exhibitions of the Museum opened in 1979. In 2000 as a member of the Advisory Board, he again was involved in the planning and creation of the reinterpretation of the Plains Indian Museum. The Lakota log house in the Adversity and Renewal Gallery is based on Amiotte’s in-depth research of such reservation houses, in particular the home of his great-grandfather Standing Bear. The house represents continuity, adaptation, and innovation that occurred in the lives of Lakota people during the early reservation period of 1880 to 1930. As Amiotte describes in his Artist’s Statement, his recent collage work has focused on this period of great change for Lakota people as they struggled to preserve their cultural identity in the new environment of the reservation.

Artist’s Statement of Arthur Amiotte[1]

In the past (1964–1985), I had always sustained my art production career by teaching in both public schools and universities. Even while teaching, however, it was most important for me to keep producing and exhibiting. I left university teaching in 1985, at age forty-three, to devote my full time to making art and have freelanced since then, having established my studio in 1986. I have continued to make art, to research as an art historian, lecturer, consultant, and arts judge based on my academic scholarship.

The most recent works from my thirty-five year career were inspired in 1988 when I completed the section-chapters on Sioux art for the centennial book, An Illustrated History of the Arts in South Dakota. I discovered contemporary Sioux artists were still romanticizing nineteenth century Sioux life and ideals in pretty, stylized forms; in reproductions of hide paintings; and, in Russell and Remington style paintings and forms influenced by southwest Indian art.

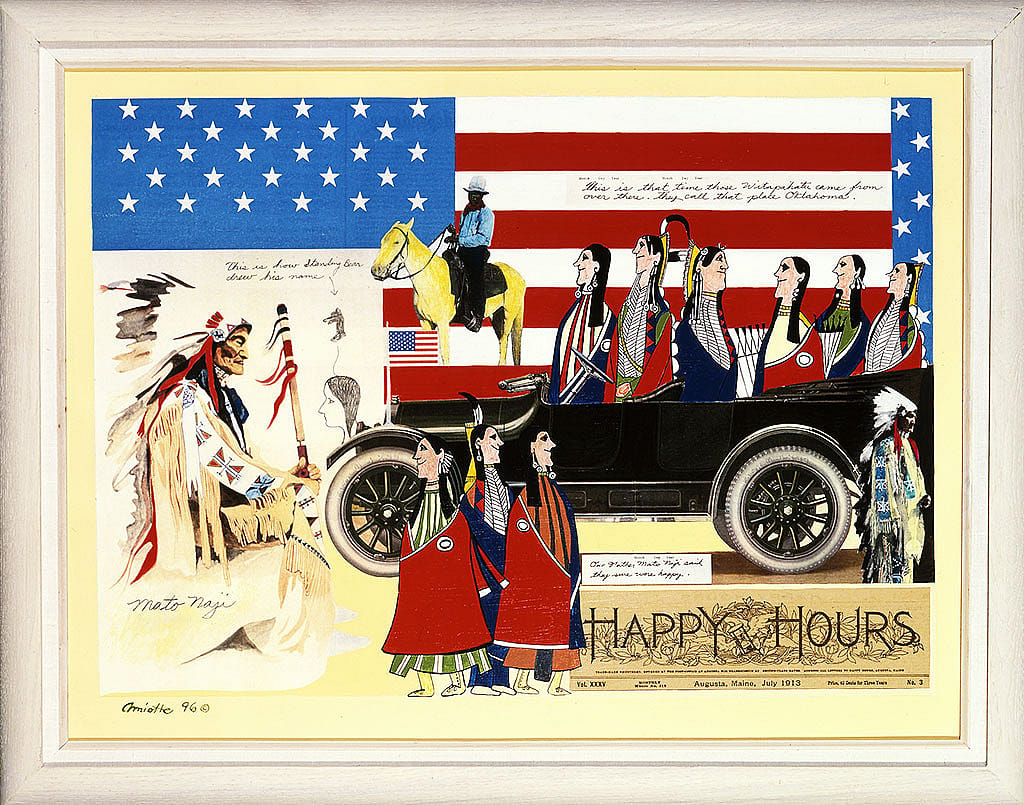

I purposefully decided to treat Sioux life from the periods of approximately 1880 to 1930, a period when culture change and adaptation were drastically taking place in the areas of technology; printed media and language; fashion; social and sacred traditions; education; and, for Sioux people, an entirely different world view.

In collage and over-painting, I utilize old family photographs—photographs I have personally taken; photographs from historical collections; laser copies of photographs of original paintings I have done in my past career; text and advertisements from antique magazines and books; pages from antique ledger books; and, copies of my hand-drawn copies or reproductions of original drawings by my great-grandfather, Standing Bear (1859–1933) who illustrated the well-known book, Black Elk Speaks, by J. Neihardt.

Handwritten text on the compositions is reminiscent of that found in old ledger books of drawings done in the aboriginal style by Sioux and other Northern and Southern Plains tribal men from the 1870s to the 1930s. The voice of the written texts is sometimes that of my great-grandfather, grandfather, grandmother, or an anonymous male or female of their generation, all reflecting on the newness of living in a white world and adapting to these strange and new ways. By synthesizing all these components and media into compositions, I feel I have created a combination of works on paper, which culminates as a work on canvas and as a painting once the over-painting, including original painted images, is completed.

I began this series in 1988 but took two years off to work on an entire room with three-dimensional collage treatments for the inaugural exhibit of the new National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, New York City Branch, and I employed the same principles as my two-dimensional works. In retrospect, all of this is also an exercise in recycling, an older practice of my people, and one all people are in need of doing at this time. In 1997, I received a Lila Wallace Reader’s Digest/Arts International Fellowship, one of five awarded from more than one thousand applicants. The beginning of this artist’s statement was part of that application. I spent from July 1 to October 27, 1997, residing and working at the last residence of Claude Monet at Giverny, France—the location of the famous gardens.

My intention was to continue with the collage series I began in 1988. In this instance, I intended to deal explicitly with the presence of Plains Indians in Europe while performing with the Buffalo Bill and other western life shows from 1887 to 1906. I researched and found images in old bookstores, in stalls on the Left Bank in Paris, and in some historical archives. I combined these images with photos and pictographic images from ledger books and muslin paintings done by my great-grandfather, the Oglala Sioux, Standing Bear, who had traveled with Buffalo Bill from 1887 to 1891 and several times later.

Great-grandfather and other local Sioux people from the Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota who had performed in Europe told many stories of having been guests of Europeans who saw the Wild West show performances and invited Indians to their homes. Sometimes, they traveled long distances from major cities where performances took place. Indian people were thus able to experience European cities and countrysides while traveling by carriage and by train. These tribal elders (by the time my generation would hear these accounts) told of the wonders they saw—palaces, castles, cathedrals, gardens, villages, rivers, and bridges—and of the spectacle of performing before royalty, including Queen Victoria in London.

In the collages I did that summer are composites of materials I used previously and photographs I took in Paris and in the countryside near Giverny, Vernon, and other parts of France. I imagined what my forebearers would have thought and experienced. I have also lived on the reservation and practiced the traditions, and now, one hundred years later, I was experiencing and wondering about this foreign land. Certain landscapes and architectural sites have remained the same over hundreds of years.

On several occasions while driving or hiking in the countryside, I would come upon a scene—a field with a barbed wire fence, a dusty narrow dirt road with muddy ruts, crops of corn or sunflowers, and even an occasional cow that had escaped its fenced-in meadow. These scenes struck me with nostalgia and a sense of deja vu since they reminded me so much of home on the reservation and certain parts of the West. Even the sounds and smells were the same. I imagined since this was happening to me, it may well have happened to my forebearers when they, too, were a little lonely in a foreign land thousands of miles away from their reservation farms, ranches, and homesteads.

Reflecting on all of this, I remembered that the old-fashioned automobile that appears in so many of my collages, sometimes anachronistically, is really a symbol of modernity—both technological and social—into which my people have been thrust and expected to master as modern citizens of the United States. The automobile is the symbolic vehicle of social and cultural change my people have had to ride in order to survive in a world order driven by change and progress. Since our white contact, it is impossible to be Noble Redmen or any other stereotypical American Indian.

One purpose of allowing Indians to leave the reservation and to travel throughout the United States and Europe with the Wild West shows was to expose them to the larger world and its powers and wonders to convince them that their indigenous ways were useless in the face of the changes wrought by the culture of the non-Indian, those who would soon overtake everything in the West. We struggle as modern Indian peoples to maintain as many vestiges of our tradition that we can.

Note:

1. John A. Day, Editor, Arthur Amiotte in Arthur Amiotte Retrospective Exhibition; Continuity and Diversity. (Pine Ridge, South Dakota: The Heritage Center, Inc. Red Cloud Indian School), p. 5–6.

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.