Native American Servicemen and World War I

APRIL 6, 1917: UNITED STATES ENTERS WORLD WAR I

In Plains Indian culture, military endeavors for men were considered one of the most honorable deeds. War achievements such as “counting coup” granted men certain rites within his society. The act of counting coup required tasks such as capturing an enemy horse; touching the first enemy in battle with his coup stick; disarming an enemy of his knife, tomahawk, spear, firearm, or bow; and leading a successful war party. According to the late Dr. Joseph Medicine Crow, “the most respected coup was to sneak into an enemy camp at night and capture a prized horse, perhaps a buffalo horse, a warhorse, even a parade horse.”[1] Young men were disciplined in these warrior traditions on the Plains. Worthy deeds such as counting coup allowed men an individualist experience and sense of responsibility to his tribe and family members.

“How I wished to count coup, to wear an eagle’s feather in my hair, to sit in the council with my chiefs holding an eagle wing in my hand”- Plenty Coups of the Crow

At the time when many Native American men and women were assimilated and forced to move to reservations, an entire tradition of military activities ended. Plains Indian men lost a major sense of identity and purpose. For the first two generations of Plains Indians on reservations, nations with a history of nomadic movement on the Plains especially struggled with confinement to their reservations.[2] Iverson and Davies suggests, “A colonial mentality persisted. Indian peoples hated being dependent for rations, being told where they could live, and being commanded how they should worship.”[3]

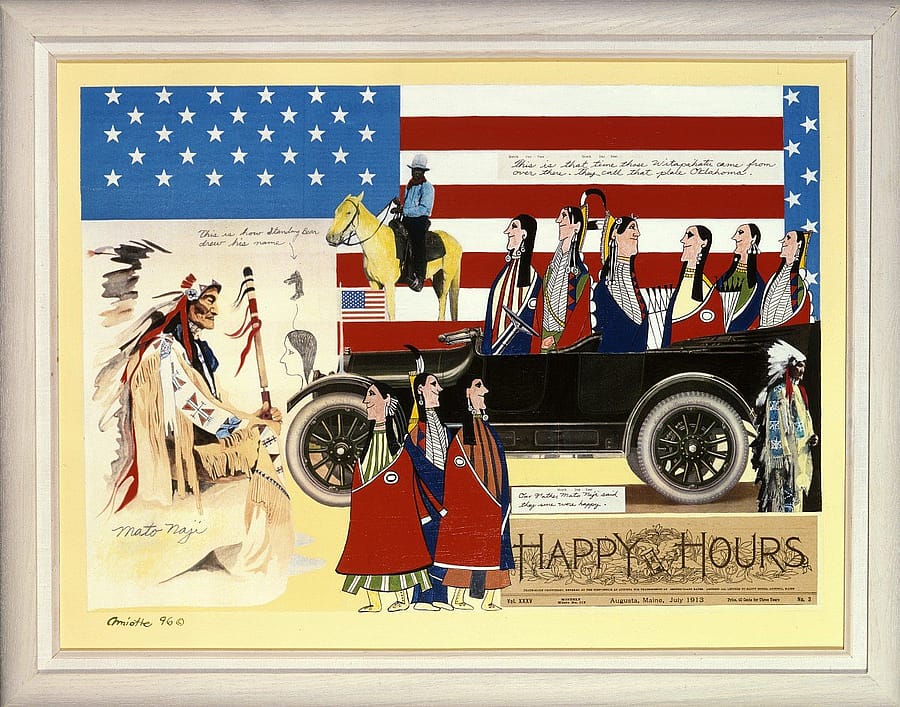

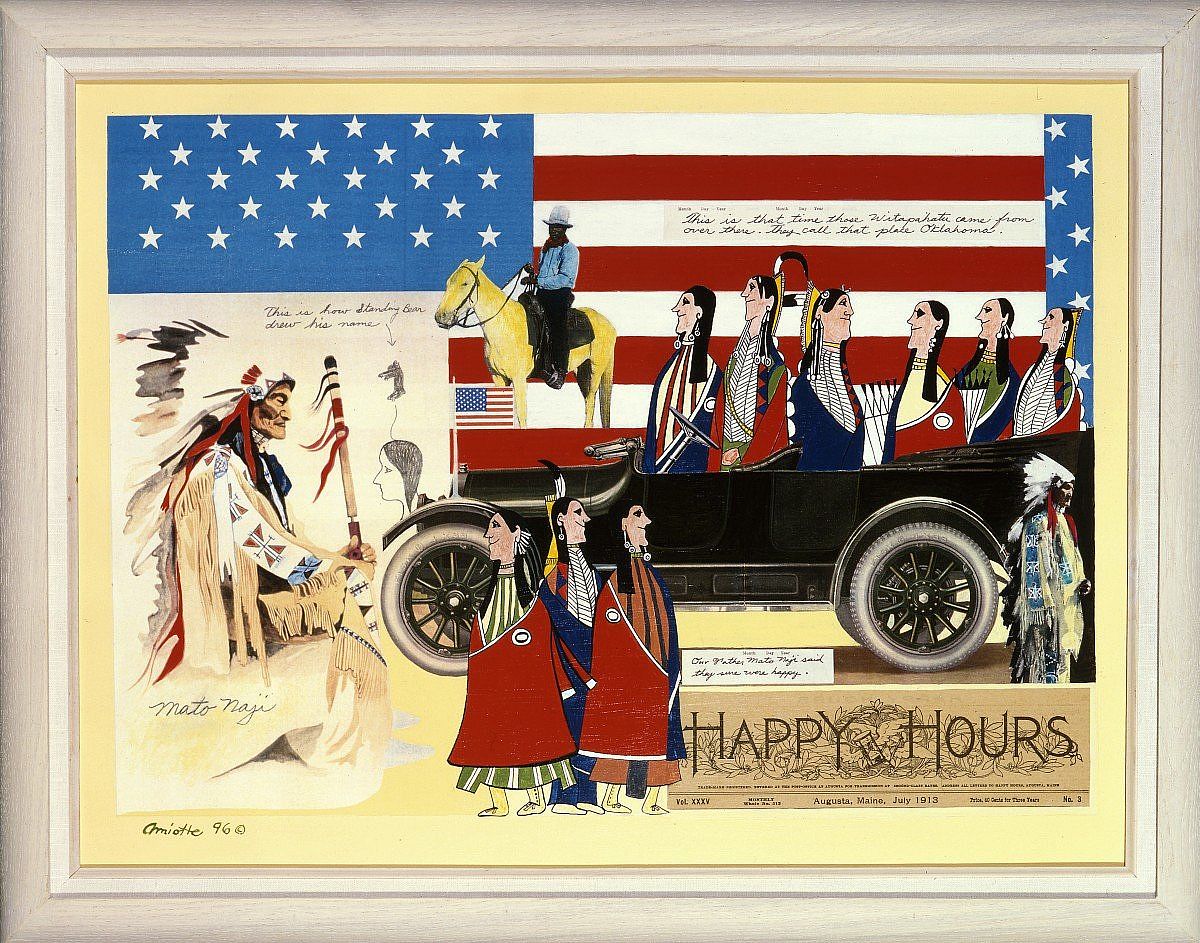

Men sought an opportunity to renew their former warrior traditions in 1917 when the United States entered World War I. Service and duty appealed to American men. This sense of responsibility was also shared in Native American communities and, encouraged by Bureau of Indian Affairs agents, federal officials, and assimilationists. Some argued that “war would accelerate assimilation and permit Indians to demonstrate their ability to contribute to American society.”[4] This unique opportunity for service was exploited, as Native Americans were not granted American citizenship and therefore ineligible for the draft. However Native men were asked to register with selective services.[5]

Native Americans experienced a few challenges while oversees. It was a belief among military leaders that Native American men possessed extraordinary abilities. Commanding officers were convinced that Natives were “natural” scouts.[6] Some men and women were also referred to by their non-Indian peers as “chief,” or in some cases, “The Indian.”[7] Others were celebrated for their cultural differences such as the use of Native code talkers representing twenty-six languages.

Some struggled with fighting for the United States because they were not considered citizen, or had experienced mistreatment from the United States. By the end of World War I, those who had served in the armed forces were offered United States citizenship. In 1924, the Snyder Act granted all Native Americans United States citizenship.

It is estimated that over 12,000 Native Americans served in World War I. Many Native communities celebrated with a resurgence of tribal warrior ceremonies before shipping abroad and upon returning. Several men earned coups against their enemies and were gifted with honor songs and rites to join tribal warrior societies. In contemporary life, Native American men and women have the highest per-capita participation in the armed forces. Indian Country Today reports:

Warrior Homecoming Honoring

According to the Department of Defense, in 2010 22,569 enlisted service members and 1,297 officers on active duty were American Indian. Considering the population of the United States is approximately 1.4 percent Native and the military is 1.7 percent Native (not including those that did not disclose their identity) Native people have the highest per-capita involvement of any population to serve in the U.S. Military.[8]

Military service is of the highest honorable tasks Native Americans participate in. Veterans are held in the highest regard. This respect is a continuation of the traditions long ago.

Notes

[1] Joseph Medicine Crow, Counting Coup: Becoming a Crow Chief on the Reservation and Beyond, (Washington D.C.: National Geographic, 2003): 10.

[2] Peter Iverson and Wade Davies, “We Are Still Here: American Indians since 1890,” (Wiley Blackwell, 2015): 41

[3] Iverson and Davies, 41.

[4] Iverson and Davies, 53.

[5] Iverson and Davies, 54.

[6] Iverson and Davies, 54.

[7] Allison R. Berstein, American Indians and World War II, (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1991): 40.

[8] Vincent Schilling, “By the Numbers: A Look at Native Enlistment During the Major Wars,” Accessed 6 April 2017. https://indiancountrymedianetwork.com/news/veterans/by-the-numbers-a-look-at-native-enlistment-during-the-major-wars/

Written By

Hunter Old Elk

Hunter Old Elk (Crow & Yakama) of the Plains Indian Museum at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, grew up on the Crow Indian Reservation in Southeastern Montana. Old Elk earned a bachelor's degree in art with a focus on Native American history at Mount St. Mary’s University in Maryland. Old Elk uses museum engagement through object curation, exhibition development, social media, and education to explore the complexities of historic and contemporary Indigenous culture. She is especially inspired by the stories of Native American women who lived and thrived on the Plains. Facebook/ Instagram: @plainsindianmuseum