June 2, 1924: 93 Years of Native American Citizenship

BE IT ENACTED by the Senate and house of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That all non citizen Indians born within the territorial limits of the United States be, and they are hereby, declared to be citizens of the United States: Provided That the granting of such citizenship shall not in any manner impair or otherwise affect the right of any Indian to tribal or other property.

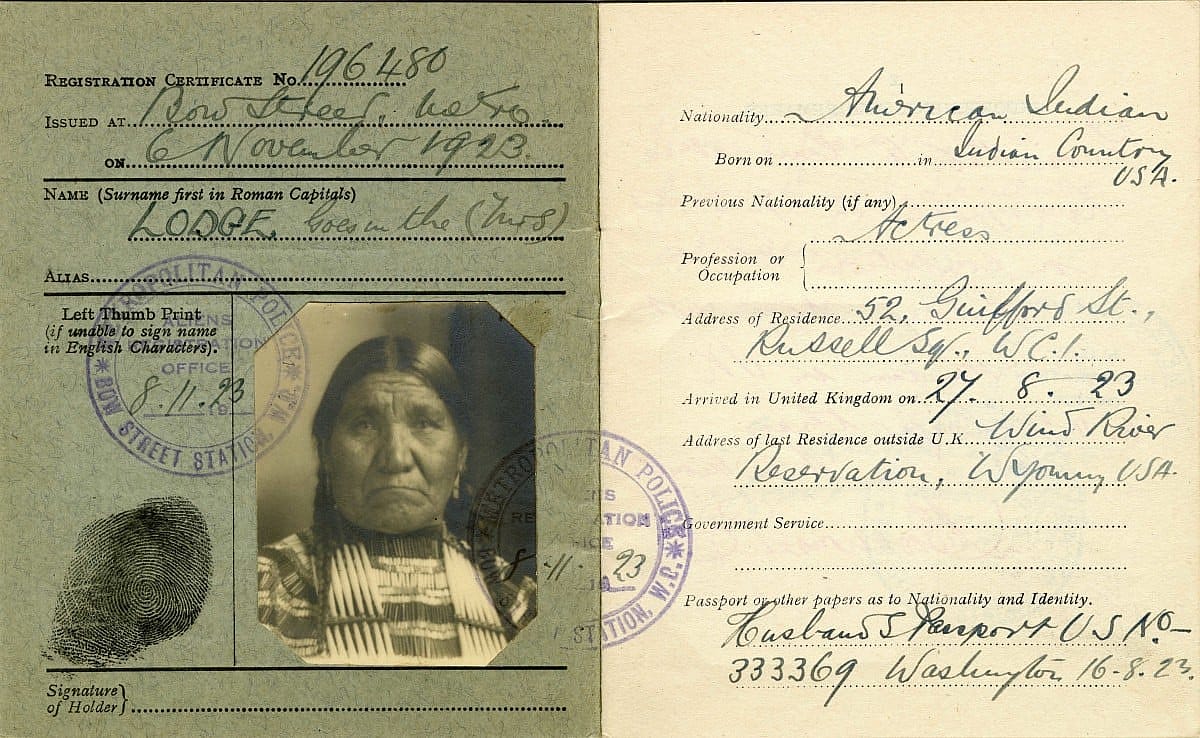

On this day, June 2nd, 1924, the United States granted Native Americans citizenship to the indigenous peoples in its territorial limits. The Indian Citizenship Act of 1924, also known as the Snyder Act, was proposed by New York Republican Representative Homer P. Snyder. Until 1924, the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution defined citizenship as those individuals born in the U.S., with the exclusion of indigenous persons. In recognition of thousands of Natives who joined the armed forces in World War I, President Calvin Coolidge signed into law the Snyder Act. At the time, nearly:

Two out of every three Native Americans already had been accorded this status including those who had taken allotments or who had served in World War I. Citizenship in and of itself surely did not change the economic difficulties plaguing Indian communities, and many Indians regarded the matter as irrelevant because of their perspectives on sovereignty.[1]

The Citizenship Act of 1924 granted approx. 250,000 Native Americans U.S. citizen status. Some scholars suggest that citizenship was intended to assimilate Natives into modern American life. Although this may have been the case, citizenship was important for many individuals who felt alienated from basic rights such as political participation and voting. For many tribes, members also maintained citizenship within their own tribal sovereign nations. Today, American Indians and Alaska Natives alone account for 2.9 million people or 2% of the United States population.[2]

[1] Peter Iverson and Wade Davies, “We Are Still Here: American Indians since 1890,” (Wiley Blackwell, 2015): 68.

[2] “The American Indian and Alaska Native Population: 2010,” U.S. Department of Commerce Economics and Statistics Administration: U.S. Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-10.pdf.

Written By

Hunter Old Elk

Hunter Old Elk (Crow & Yakama) of the Plains Indian Museum at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, grew up on the Crow Indian Reservation in Southeastern Montana. Old Elk earned a bachelor's degree in art with a focus on Native American history at Mount St. Mary’s University in Maryland. Old Elk uses museum engagement through object curation, exhibition development, social media, and education to explore the complexities of historic and contemporary Indigenous culture. She is especially inspired by the stories of Native American women who lived and thrived on the Plains. Facebook/ Instagram: @plainsindianmuseum