Mysterious Plains Borderlands

In the Nakoda (Assiniboine) language, the border separating the U.S. and Canada is sometimes referred to as the Ĉaŋgú Wakaŋ, which can be roughly translated as the “mysterious road/trail.” When this border was created in the second half of the 19th century, it cut through the middle of lands that the Nakoda have called home since Creation. One of the characteristics that make this trail mysterious is that it is invisible. Another is that, despite its invisibility, it had the power to stop any group of charging mina hanŝka (“long knives”—the name we used to describe U.S. soldiers) right in their tracks. Lastly, the Ĉaŋgú Wakaŋ had—and still has—the power to separate and segregate communities and families under the jurisdiction of entirely different countries and beliefs.

The Nakoda are not the only Plains Indian community that is bisected by the international Ĉaŋgú Wakaŋ border with Canada. The Niitsiitapi (Blackfoot community), nehiyâw (Plains Cree), Lakota (Sioux), and Dakota (Sioux) communities are also divided, with reserves/reservations on both sides of the border. During the late 19th century, the U.S. Army was charged with enforcing this invisible trail by, among other ways, deporting the “British (Canadian) Indians” vs. “American Indians” (since Canada was a dominion of Britain then).

During deportations in the late 19th century, the nehiyâw (Cree) and Nakoda were particularly targeted, as they were erroneously and unjustly perceived as having little attachment to U.S. soil. Anyone even suspected as being a “British Indian” was deported and had their arms and horses confiscated by the military. Sometimes the people deported had never even spent time on ‘Canadian’ soil before. This was problematic for many reasons.

For one thing, people’s identities during this time were fluid, as many Nakoda were bilingual in both Nakoda and nehiyâw (Cree) languages and were heavily intermarried with their nehiyâw (Cree) relations. A Nakoda individual, for instance, may reside in a “Nakoda band” (a band is just a tribal subdivision) for part of his/her life, then later switch affiliation due to a change in leadership or a marriage, and thus now reside in a “nehiyâw band” for the remainder of his/her life. Furthermore, many bands had migratory movements that would seasonally take them from what is now one side of the U.S.-Canada border to the other.

The Síhabi Nakoda (Foot People) bands and especially the Ĥebina Nakoda (Rock Mountain People) bands that my relations are descended from, for example, would often hunt buffalo and establish winter camps along the Ogíĉiza Wakpá (Battle River) in the area southeast of present-day Edmonton, Alberta. At the same time, however, it was necessary for us to hunt and trade, as well as fight enemies, south of the Ĉaŋgú Wakaŋ along the Miníšoše (Missouri River). Not just my relatives but other bands of Nakoda and nehiyâw peoples would do the same. This illustrates the impossible imposition of a ‘Canadian’ or ‘American’ title to our people.

The imposition of the U.S.-Canada border is still felt today, as Nakoda, nehiyâw, Niitsiitapi, Lakota, and Dakota communities are divided by land and designations of either “American Indian” or “First Nations.” And due to the government’s difficulty in restricting the movement of Nakoda and nehiyâw peoples from crossing the Ĉaŋgú Wakaŋ in the 19th century, today most Canadian reserves are located far along the northernmost part of our range, further isolated by a multitude of various tiny reserves contrasting to the large, more consolidated reservations that are in the U.S. The strategy of making various tiny separated reserves, along with a pass system that prevented people from leaving their reserves, was Canada’s way of “securing the border” and opening lands for immigrant settlement.

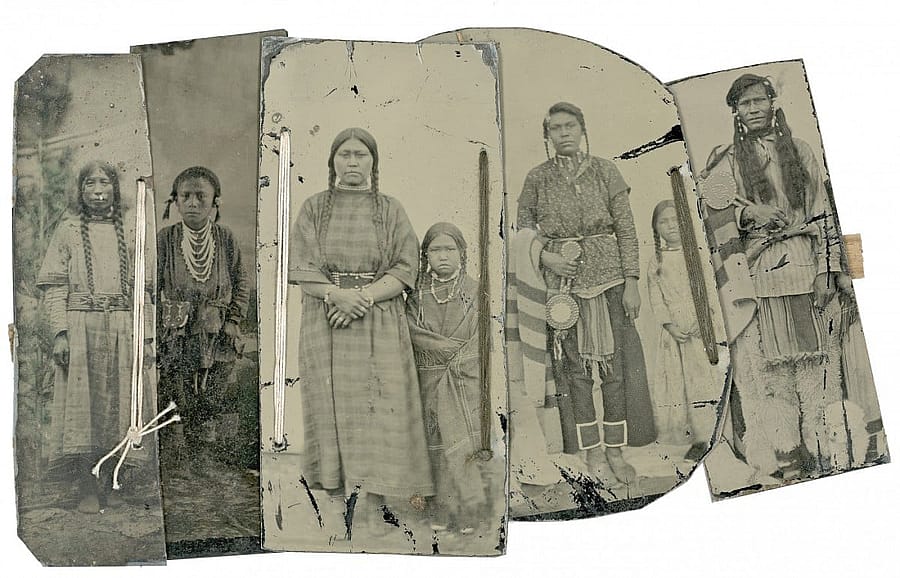

Today, people are allowed to move within the lands that we were made a part of, and here at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West’s Plains Indian Museum, visitors can learn from objects that belong to the people from Canada and the U.S. The Paul Dyck Collection exhibition, in particular, features an abundance of objects from both “Canadian” and “American” peoples side by side, as Paul Dyck lived and acquired objects from both countries during his life. I invite the readers to visit the different exhibits in the Plains Indian Museum and the other museums here at the Center, and learn more about the fluidity of us Plains peoples through our objects and stories.

Written By

Ernest Gendron

Ernest is a Nakoda-Cree educator working seasonally at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West with both the education department and the Plains Indian Museum. He is a craftsman of Nakoda-Cree ‘male’ arts, such as bows and arrows, clubs, horn spoons, etc. He is also a consultant on Plains Indian history. When not on site, he is working on his thesis in pursuit of a Master’s degree in Heritage Management.

![Wahúkeza [lance]. NA.108.159](https://centerofthewest.org/cdn-cgi/image/width=600,height=400,fit=crop,quality=80,scq=60,gravity=auto,sharpen=1,metadata=none,format=auto,onerror=redirect/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/NA.108.159.jpg)