Plains Indian Weapons—Part I: Bow and Arrows

In a series of blogs on men’s weaponry on the plains, I will discuss several different weapons, beginning with perhaps the most well-known: the bow and arrow.

For the Nakoda, like most Plains Nations, the bow, idazipa, and the arrow, wohiŋkpe, are indispensable weapons. Their origins are sacred, as the use of them was handed down from Iŋkdomi (our name for the Trickster, who was also involved in earth’s re-creation). The bow and arrows both fed and protected the people. Because of their importance, young men learned from the time that they could stand how to handle them, and were also taught how to construct them from their older male relatives. Plains bows are commonly made of ĉaŋsuda (ash), ĉaŋpá (chokecherry), or watʾéyaga (juniper) in the north, and osage orange in the south. Arrows are constructed from ĉaŋŝaŝa (red osier dogwood), or sometimes made of wiŋbazogaŋ (juneberry) or ĉaŋpá (chokecherry).

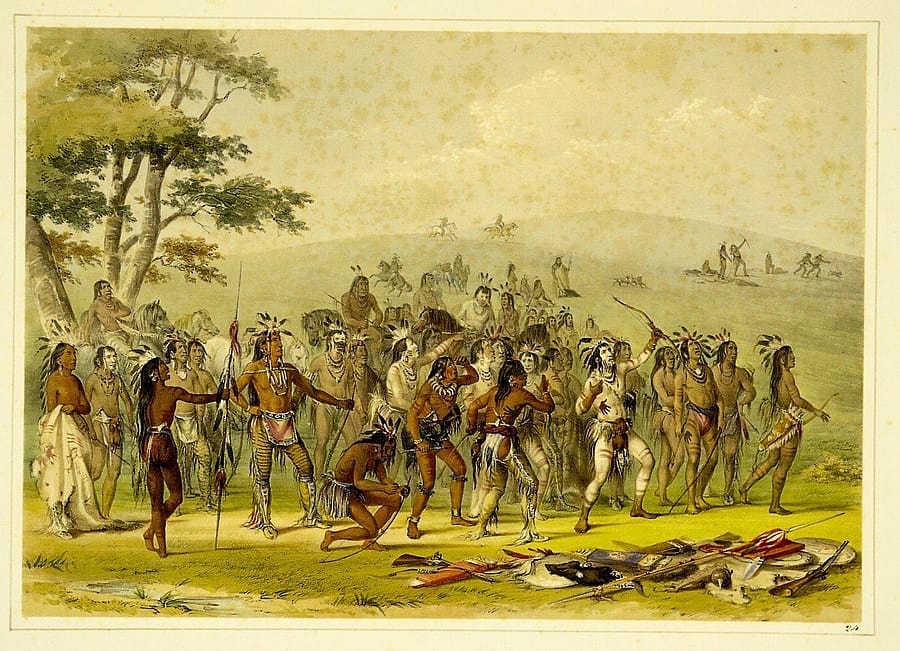

Early immigrant-travelers on the plains, such as Alexandre Henry, noted that even after the introduction of firearms, men never went anywhere without a bow and arrows. Many chroniclers left accounts of just how proficient the people were with them. George Catlin, for example, spoke of men at the Missouri River villages playing an “arrow game,” where they competed for speed, shooting as many arrows into the air as they could before the first one hit the ground. He noted that men could often let fly eight arrows before the first one reached the ground![1]

The bows were also powerful, as mentioned by Paul Kane in his travels. Of Nakoda bows and arrows, he wrote, “these they use with great dexterity and force; I have known an instance of the arrows passing through the body of an animal [buffalo], and sticking in the ground at the opposite side.”[2]

To enable men to efficiently use bows and arrows from horseback (once horses were available), Plains bows and arrows are uniquely designed and constructed for mounted use. For maneuverability they are short (~42-48″), and often reflexed with a distinctive “gull-wing” profile that gives a short bow the maximum amount of power for its size. The bows are often further strengthened by being “sinew-backed.”

The sinews of buffalo or elk are dried, pounded into fine threads, and glued to the back of the bow in layers using glue made from hide scrapings/sinew scraps mixed with water. This layering of sinew and glue has the effect of making the bow faster-shooting, more powerful, and sturdier against breakage (avg. draw-weight of 50-70 lbs). Some men would even go a step further by gluing rattlesnake skins over-top of the sinew backing, to protect the backing from the weather.

Truly a weapon for any age, there are men from many of our Buffalo-Nations that continue to make and use our distinctive archery equipment of the Plains.

For more info on Plains Indian bows:

- [email protected] [Nakoda bow/arrow maker Ernest Gendron]

- https://www.facebook.com/lakotabows/ [Lakota bow/arrow maker Richard Giago]

- www.plainsindianbows.com/ [Chickasaw bow/arrow maker Eric Smith]

[1] Catlin, George. Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Condition of the North American Indians: Written During Eight Years’ Travel in 1832-1839. Vol. 1. Tilt and Bogue, 1842, p. 141-142.

[2] Kane, Paul. Wanderings of an Artist among the Indians of North America. Courier Corporation, 1996, p.96.

Written By

Ernest Gendron

Ernest is a Nakoda-Cree educator working seasonally at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West with both the education department and the Plains Indian Museum. He is a craftsman of Nakoda-Cree ‘male’ arts, such as bows and arrows, clubs, horn spoons, etc. He is also a consultant on Plains Indian history. When not on site, he is working on his thesis in pursuit of a Master’s degree in Heritage Management.

![idazipa [bow--note gull-wing form/reflex]. NA.102.41](https://centerofthewest.org/cdn-cgi/image/width=1200,height=150,fit=crop,quality=80,scq=50,gravity=auto,sharpen=1,metadata=none,format=auto,onerror=redirect/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/na.102.41-idazipa.jpg)

![idazipa [bow--note rattlesnake skin]. NA.102.219](https://centerofthewest.org/cdn-cgi/image/width=900,height=308,fit=crop,quality=80,scq=50,gravity=auto,sharpen=1,metadata=none,format=auto,onerror=redirect/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/na.102.219-idazipa.jpg)

![Wahúkeza [lance]. NA.108.159](https://centerofthewest.org/cdn-cgi/image/width=600,height=400,fit=crop,quality=80,scq=50,gravity=auto,sharpen=1,metadata=none,format=auto,onerror=redirect/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/NA.108.159.jpg)