Revisiting “The Flamboyant Fraternity”

This article was originally authored by former Curator of History Paul Fees, and was published in a 1981 Buffalo Bill [Center of the West] newsletter.

When the Hon. William F. Cody took his Wild West to England in 1887 and to France in 1889, he was an immediate hit. In a short time he would become probably the best known and best loved American in Europe since Benjamin Franklin, who had conquered French society with suavity, wit, and coonskin cap a century before. For Buffalo Bill was another of America’s “Nature’s Noblemen,” reared in the wilderness yet endowed with the graces of civilization. For Europeans, there was something more in Buffalo Bill’s persona and his reputation that made him universally and instantly recognizable. He was the very picture of the romantic cavalier. “The Bayard of the Plains” a British newspaper dubbed him after the legendary 16th century French “chevalier sans peur et sans reproche,” the knight without fear or blame.

Buffalo Bill was undoubtedly aware of the impression his appearance would make as he rode into the arena with his thigh-high boots and vast sombrero, moustache, goatee, and dark flowing hair.

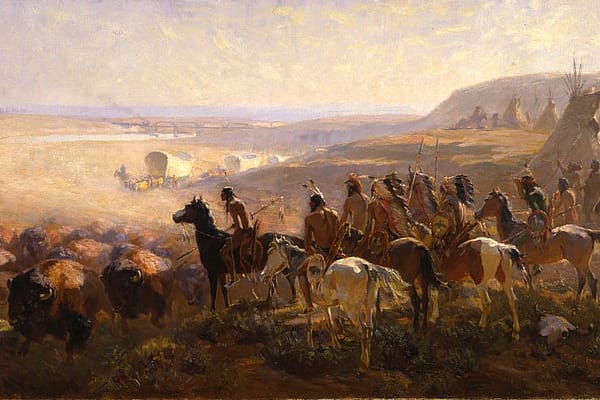

As a prairie scout in the 1860s and 1870s, he had been part of a self-consciously extravagant brotherhood—extravagant in dress, name, and gesture.

Because they were civilian employees of the army and employment was spotty, scouts remained largely independent. They were well-paid because they were highly skilled and possessed insiders’ knowledge of Indian culture. They asserted their special status by donning eccentric or splendid attire, by growing their hair to their shoulders, by wearing nicknames as “titles.” And why not? Theirs was an uncertain and extremely hazardous profession. Many of Buffalo Bill’s confreres—among them, California Joe Milner, Buffalo Chips White, and Medicine Bill Comstock—died violently during the Indian wars.

Some scouts apparently cast themselves in the mold of romantic chivalry. One impetus may have been their familiarity with the cavalier tradition of the ante-bellum South. Another may have been their close association with gentlemen officers of the U.S. Cavalry.

Wealthy Englishmen who were guided on big game hunts by scouts such as Jim Bridger and Buffalo Bill were often purveyors of adventurous romance. Sir George Gore in 1853 used to read aloud around the campfire from such chivalric stuff as the novels of Sir Walter Scott. It is not unlikely that Alexandre Dumas’ The Three Musketeers reached the plains within a few years after it was published in 1844.

Kit Carson’s life, already memorialized in dime novels and sensational biographies by the 1860s, provided a model of gallantry and modesty for his frontier successors. Buffalo Bill, for one, idolized the great scout and named his only son Kit Carson Cody.

The romantic appeal of the scout cavalier was recognized, even encouraged, by contemporaries. A member of the Earl of Dunraven’s hunting party wrote of young Bill Cody and Texas Jack: “If Buffalo Bill belongs to the school of Charles I, pale, large-eyed, and dreamy, Jack, all life, and blood, and fire, blazing with suppressed poetry, is Elizabethan to the backbone!”

Amateur drama was a favorite diversion at frontier military posts, and not surprisingly quite a few scouts found their way easily and naturally into the flamboyant world of the theater—Texas Jack Omohundro, Wild Bill Hickok, Captain Jack Crawford, Buckskin Sam Hall, and others. But none matched the success of Buffalo Bill.

His stature was heroic, his demeanor modest and courteous, his bravery and generosity unquestioned. Perhaps more important, he understood the link with the chivalric past and institutionalized it. The title of his popular Prentiss Ingraham drama of 1879 was “The Knight of the Plains.” He wrote a story the same year called “Gold Bullet Sport; or, the Knights of Chivalry.” His press and public frequently pointed out romantic and classical predecessors. One reporter even termed Buffalo Bill “the rival of Horatius Cocles,” the Roman hero remembered as “Horatio at the Bridge.”

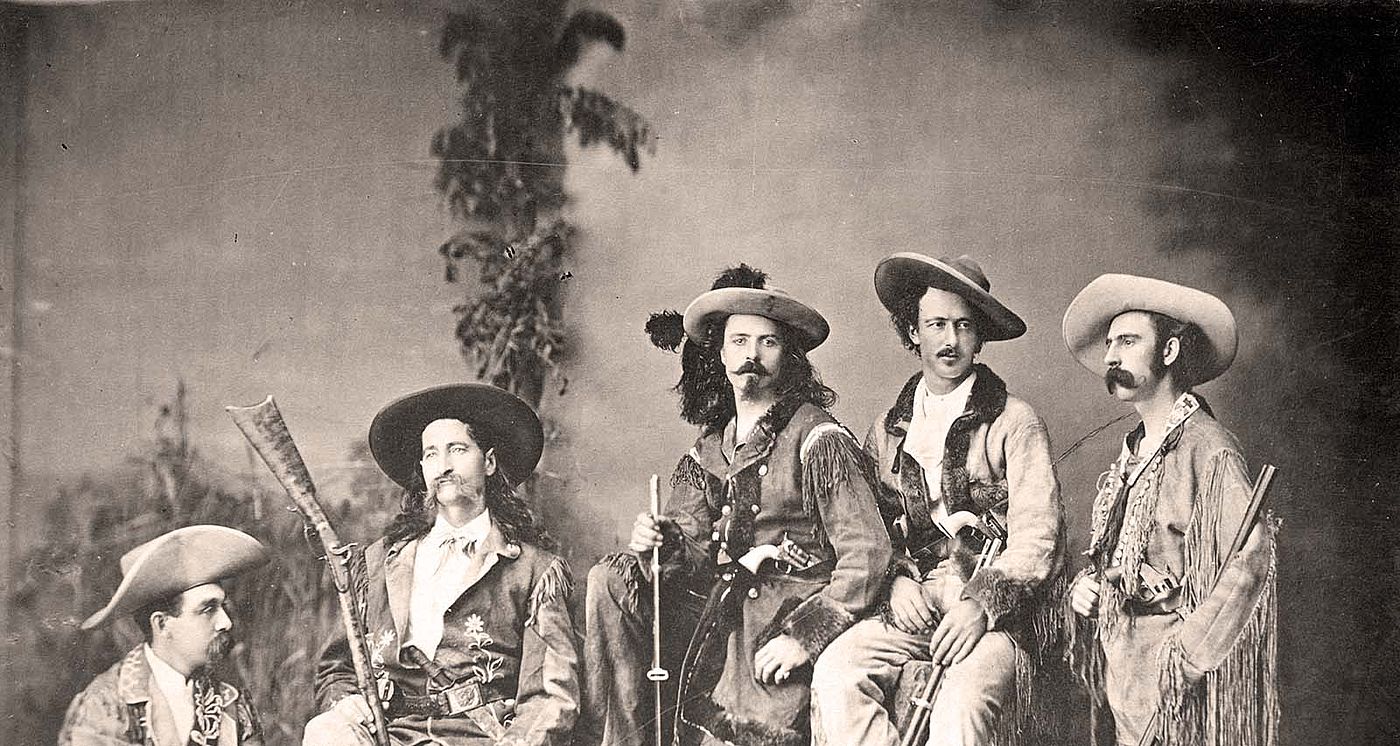

When the photograph above was taken in 1873, Buffalo Bill and his fellow scouts were already comfortable in their resplendent knighthood. An English newspaperman was only confirming the obvious for his readers when he said of Buffalo Bill in 1887, “his life is a history of hairbreadth escapes, and deeds of daring, generosity, and self-sacrifice, which compare very favorable with the chivalric actions of romance.” He looked the cavalier; he was the cavalier.

Written By

Michaela Jones

Michaela, a Cody, Wyoming native, is the Centennial Media Intern at the Center of the West for the summer of 2017. She recently graduated from the University of Wyoming with a bachelor's degree in English and minors in professional writing and psychology. She's interested in writing for digital spaces, producing social media content, and learning about technology's impact on communication. In her spare time, she enjoys reading non-fiction, exploring the mountainous Wyoming regions, and spending time with family and friends.