Part II: Beautiful, Daring Western Girls

“Beautiful, Daring Western Girls,” by Sarah Wood-Clark, former assistant registrar, was originally published in a 1983 Buffalo Bill [Center of the West] newsletter. This blog post is the second post of two. To read the first post, click here.

Etheyle Parry and her twin sister, Juanita, left their homes in Riverhead, Long Island, as teenagers to become trick riders with the 101 Ranch Real Wild West. Programs for the exhibition claimed they were born on an Oklahoma ranch. A friend later described Etheyle as “the boarding school type.”

Lillian Ward, a Brooklyn socialite, went to a Texas ranch for her health and later joined Buffalo Bill’s Wild West as a bronc rider. Adele Parker was raised in New Jersey.

Although some materials seldom directly address the issue, these equestriennes must have experienced conflict between society’s expectations of them as women and their chosen occupations. For example, Della Ferrell, described as a rough rider with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, noted that she found it very difficult to learn to ride astride. Although it is a more natural and comfortable riding style, the custom of riding sidesaddle, several centuries old, was not easily abandoned.

Orilla Downing, a distaff rider with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, apparently had mixed feelings about her experience as a cowgirl. She reportedly never discussed it unless asked. Her recollections of performing were limited to vignettes such as “Pride of the Prairie,” which featured the cowgirls sitting around a campfire singing western songs. She said her husband, a bronc rider, asked her to join the show and because she could ride well she consented.

Roughly 10 percent of the caster members of a Wild West exhibition were women employed as performers. Oddly enough, very few women were hired for cooking, laundry or other traditionally feminine chores.

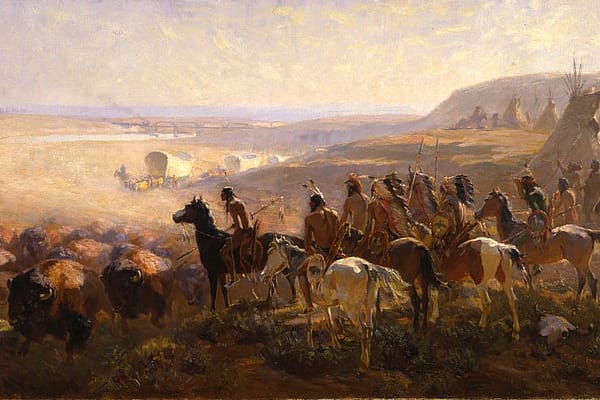

The first lady star was Annie Oakley. As early as 1880s, lady sharpshooters enjoyed immediate public acceptance. At that time the other female employees were actresses in stagecoach or train robbery scenes and enactments of Indian attacks. They were domestic women, victimized and then rescued by men in the popular melodramatic style.

In the early 1890s they began to participate in races, bronc riding, trick riding and fancy roping events. They adopted divided skirts which were more practical for these activities and developed colorful and distinctive arena attire. Each costume was truly unique—handmade and decorated with fringe, beads, conchos, coins, quillwork and painted designs. Tailors would not make divided skirts so individual women designed their own.

Indian women were also an integral part of the Wild West exhibitions. They traveled with their families and attracted attention and acclaim simply by carrying on day-to-day chores on the backlot. Indian village life was a popular feature in performances. While the itinerant lifestyle allowed some of the same advantages as the white women, they were not given or did not choose breakaway roles.

Each Wild West exhibition featured specialized events. Doc Carver’s Wild West had a woman on a driving horse. Lillian Ward and her horse jumped a table of seated diners. Zach Mulhall’s exhibition at the 1900 St. Louis World’s Fair had a Mexican woman steer riding and Pawnee Bill’s Far East show included lady elephant riders. Audiences thrilled to see each variation performed by individuals, proud of their talents and walking the same fine line as Adele Parker, who remembered all her life her mother’s advice: “No matter what you do, always be a lady.”

Written By

Michaela Jones

Michaela, a Cody, Wyoming native, is the Centennial Media Intern at the Center of the West for the summer of 2017. She recently graduated from the University of Wyoming with a bachelor's degree in English and minors in professional writing and psychology. She's interested in writing for digital spaces, producing social media content, and learning about technology's impact on communication. In her spare time, she enjoys reading non-fiction, exploring the mountainous Wyoming regions, and spending time with family and friends.