The Congress to William F. Cody

This article was originally written by Paul Fees, former Buffalo Bill Museum curator, and featured in a summer 1984 newsletter.

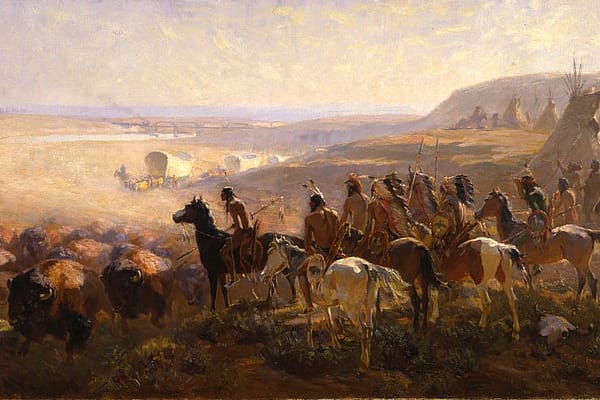

William F. Cody, guide, age 26, was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor on May 22, 1872. The Medal of Honor was, and still is, the nation’s highest decoration for gallantry. Aside from the written commendations of his comrades and commanders, the Medal of Honor is the most important emblem of Cody’s valorous services as cavalry scout and guide during the Indian Wars.

In 1916, because of abuses in the awarding of medals, Congress ordered the War Department to review the cases of Medal of Honor winners. The Adjutant General’s Office (AGO) required that three criteria be applied to the investigations: first, that the action took place in time of war; that the recipient distinguished himself above his fellows (the phrase “above and beyond the call of duty” did not gain currency until after 1897); finally, that the recipient was a member of the armed forces.

The Judge Advocate General’s (JAG) report to the AGO on November 3, 1916, concluded in Cody’s case that all three conditions were met.

First, though war had not been declared, a general state of hostilities existed on the plains in 1872. Second, the JAG concluded that the report of Cody’s actions “shows skill, bravery and leadership to a greater degree than is ordinarily expected of a scout” and that “the officer making the report deemed his act one of special gallantry.”

Finally, though Cody was a civilian scout under contract to the Army, the JAG wrote, “I have no doubt that Cody was serving in the military service of the United States at the time he distinguished himself in action.” Accordingly, on November 6, 1916, the secretary of War authorized the Medal of Honor Certificate be sent to Cody and enrolled him on the new Army Medal of Honor Roll. On November 29, just six weeks before he died, Cody acknowledged (on Irma Hotel stationary) his receipt of the Certificate.

Subsequently, under congressional mandate, the War Department revised the rules of eligibility for the medal to include, retroactively, only “officers and enlisted men.” In 1917, only because he had been a civilian at the time of the action, William F. Cody’s name was stricken from the Medal of Honor roll.

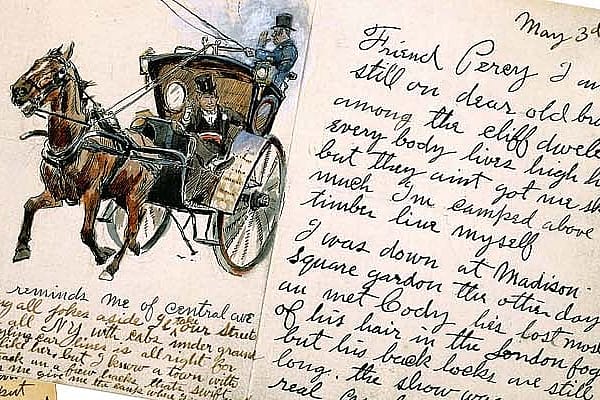

The medal itself was not recalled by the Army. Two versions were thought to exist. In fact, Cody’s foster son, Johnny Baker, had one in his collection. According to specialist in the Army’s heraldry department, the engraving on the Baker medal is of a later style. This has led to speculation that Cody’s medal had been prepared and delivered to him several years after the action in 1872. However, letters ordering the medal to be engraved (May 22, 1872) and to be conveyed through Col. J.J. Reynolds, commander of the 3rd U.S. Cavalry (May 31, 1872), survive in the National Archives. It is now speculated that Cody acquired a replacement outside normal channels, perhaps through the offices of his good friend, Nelson Miles, who became commander in chief of the Army in 1895.

Because he was naturally diffident about his wartime accomplishments (a surpise to those who expected him to be boastful), Cody seldom wore his medal publicly and almost never talked about it. The engagement for which he was decorated was a relatively minor skirmish compared to other in which he took prominent part. He did not even mention it in his autobiography, but he acknowledged and grew to appreciated the high honor that the nation had extended him.

In 1983 the Buffalo Bill [Center of the West] acquired the “lost” Congressional Medal of Honor, judged by U.S. Army historians to be likely the one presented to Cody in 1872. We are honored to exhibit it, not only for its importance in chronicling the career of William F. Cody, but because it is an American symbol recalling two centuries of duty and patriotic sacrifice.

Written By

Michaela Jones

Michaela, a Cody, Wyoming native, is the Centennial Media Intern at the Center of the West for the summer of 2017. She recently graduated from the University of Wyoming with a bachelor's degree in English and minors in professional writing and psychology. She's interested in writing for digital spaces, producing social media content, and learning about technology's impact on communication. In her spare time, she enjoys reading non-fiction, exploring the mountainous Wyoming regions, and spending time with family and friends.