Please, Mr. Custer

This article was originally published in a 1986 Center of the West newsletter and written by former curator Paul Fees.

When you say “Custer,” what comes to mind?

His power as a symbol is such that most of us immediately conjure up a strong, often complex picture—flamboyant Civil War hero, boy general, controversial victor at the Washita, invader of the Black Hills, star witness in a War Department probe, reckless fool, glorious hero, dead at 36.

“This thing about being a hero is to know when to die,” said Will Rogers.

Certainly Custer was at the pinnacle of fame when he was killed. But the events of 1876 and the demands of America’s western mythology helped determine his immorality.

The theme of the Centennial year, 1876, was Progress. At the national exposition in Philadelphia, the star exhibit was the gigantic Corliss steam dynamo which inspired historian Henry Adams and others with visions of unlimited machine power.

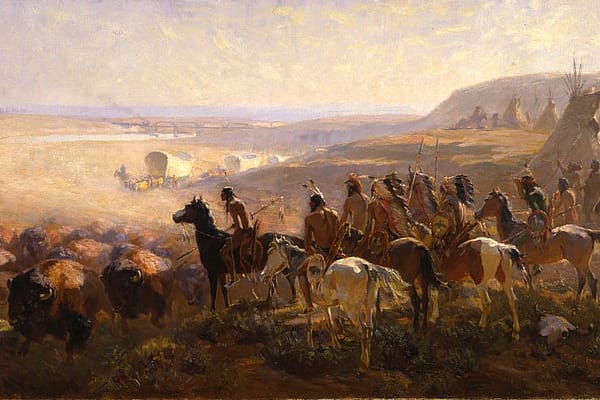

The paintings selected for the art show at Philadelphia celebrated sentimental and pastoral landscapes and a benign wilderness. In art as well as science, Americans felt they had conquered nature.

Custer’s Last Stand proved them wrong.

The news from the Little Big Horn shattered American complacency. Hordes of half-naked savages, so it seemed, had overwhelmed the flower of U.S. fighting men—and all within a few days’ ride of railroads, telegraphs, and modern cities.

Custer and his men, defenders of civilization, were America’s blood sacrifice to Progress, to the Winning of the West.

Within days of the disaster, Walt Whitman, describing the western plains as “the fatal environment,” wrote: Continues yet the old, old legend of our race, the loftiest of life upheld by death, the ancient banner perfectly maintained, O lesson opportune, O how I welcome thee!

Custer’s Last Stand was already performing a mythic function. It admonished Americans, as the chosen bearers of the torch or civilization. Never to relax in the face of darkness and barbarism.

Custer has since become a symbol of many other things, of course, from chivalry to racism to comical overconfidence.

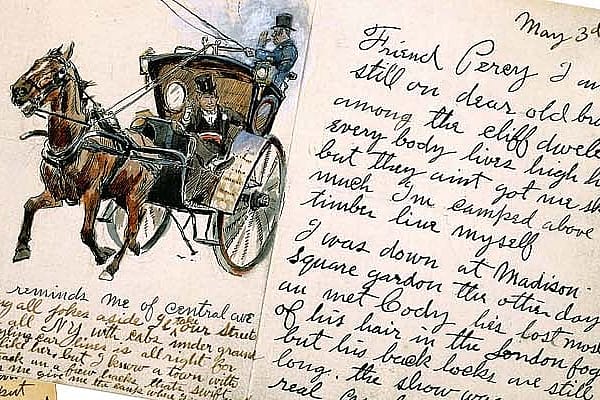

“Please, Mr. Custer,” implores one popular song. “I don’t want to go.” His image in prints, pulp novels, comic books, movies and other popular arts, has changed over time to reflect prevailing public values.

The Custer mystique is manifested in endless debates and archaeological digs, all trying to reconstruct a day over a century ago. Toys, puzzles, mugs, cigars, books, calendars, decanters, cartoons, graffiti, jokes, bumper stickers and posters are visible evidence of an American obsession.

It has been Custer’s fate to be a counterpoint to success in America’s western myth. Without Custer’s loss, conquest of the West would have somehow seemed too easy.

Winner or loser, Custer’s mystique endures. The more we examine it, the more we learn about ourselves.

Written By

Michaela Jones

Michaela, a Cody, Wyoming native, is the Centennial Media Intern at the Center of the West for the summer of 2017. She recently graduated from the University of Wyoming with a bachelor's degree in English and minors in professional writing and psychology. She's interested in writing for digital spaces, producing social media content, and learning about technology's impact on communication. In her spare time, she enjoys reading non-fiction, exploring the mountainous Wyoming regions, and spending time with family and friends.