Joseph Henry Sharp brings the Arts and Crafts Movement West – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Spring 2010

Joseph Henry Sharp brings the Arts and Crafts Movement West

By Laura Fry

Former Education and Curatorial Assistant, Whitney Western Art Museum

In opposition to the industrial revolution of the mid-1800s, leaders of the American Arts and Crafts Movement encouraged a return to good craftsmanship, individual creativity, and unique American designs—values they felt were lost due to mass production. When artist Joseph Henry Sharp designed his small, sturdy log home on the Crow Agency in Montana, he incorporated those principles. With his new home, Sharp moved his everyday life closer to his work as an artist, painting the cultures and land¬scapes of the American West.

Absarokee Hut

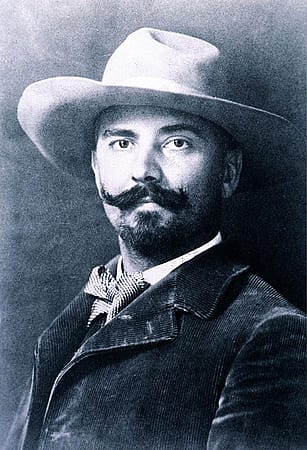

Sharp was born in Bridgeport, Ohio, in 1859, and as a young man studied art at the McMicken School of Design (later the Cincinnati Art Academy). He completed his training as a painter by traveling and studying in Europe, and in 1892 he accepted a teaching position at the Cincinnati school.

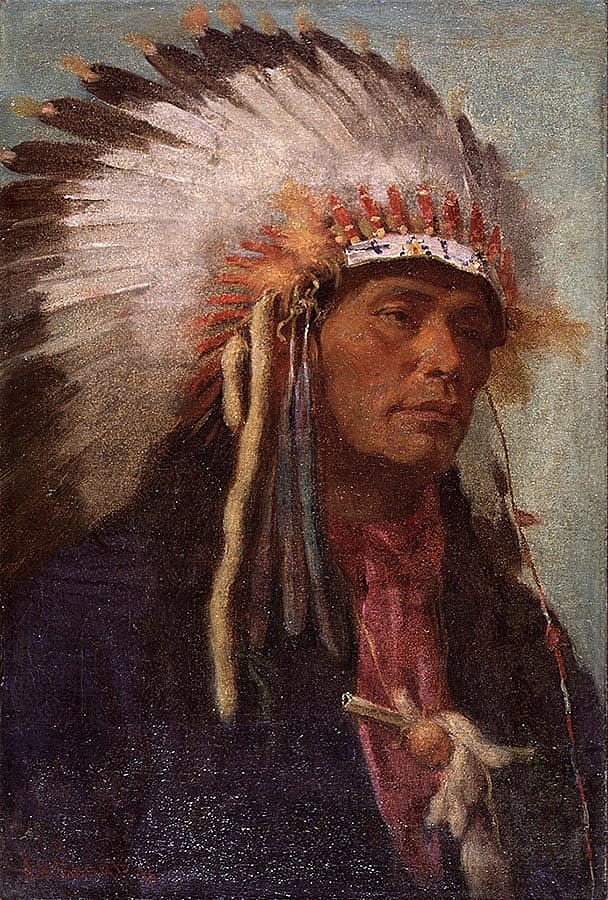

In 1899, Sharp traveled to the Crow reservation in southern Montana for the first time. He admired the artistry and beauty of the Crow people, and he started a series of Native American portraits. In 1903, he left his position at the Cincinnati Art Academy, moved to the Crow Agency with his wife Addie, and devoted himself to painting.

Sharp designed his log home in 1905, and he found working on the cabin more demanding than painting. Sharp explained, “I have ‘calouses’ on my hands, ‘charley-horses’ in both arms, and various cuts and bruises from hatchet, saw, and chisel. It’s lots of fun.” He named his home “Absarokee Hut,” after the Crow people’s name for themselves. For the concept and design of the cabin, Sharp used the ideas of the American Arts and Crafts Movement.

Arts and Crafts, from England to America

The Arts and Crafts Movement began in England in the mid-nineteenth century, while the country was in the midst of increasing industrial mass-production. The early Arts and Crafts reformers believed that the industrial revolution turned creative craftsmen into anonymous laborers. The reformers rejected mass-produced goods and favored a return to individual handwork. William Morris, a leader in the Arts and Crafts Movement in England, reunited art and labor by starting a company where workers produced creative, handmade goods. Morris & Co. inspired many similar organizations in England and the United States.

The principles of the Movement first found a wide American audience at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. From 1876 to roughly 1920, Arts and Crafts ideals influenced a variety of American artists, designers, and companies. The American movement advocated using local materials and simple, utilitarian designs without excess ornament. To develop a truly “American” style, some designers incorporated geometric motifs from Native American pottery and basketry into their goods. Periodicals such as the Craftsman promoted the idea of a “Craftsman home,” designed to integrate life and work.

Joseph Henry Sharp came into contact with the Arts and Crafts Movement when he visited the international expositions of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. As he built his Montana home, he embraced those ideals. While mass-produced board lumber was available on the Crow Agency, Sharp chose to build a log cabin, an older, simpler, and distinctly American style of architecture. In a letter to Craftsman magazine, Sharp wrote, “From the start we planned our house for comfort and for roominess…with a view to harmonious effects so far as color and line were concerned.”

Sharp hand-stained the interior woodwork and the bricks of the fireplace, and decorated the walls with a variety of Native American objects. He finished Absarokee Hut with items produced by Rookwood Pottery, Roycroft, and Craftsman Workshops—all leading companies of the American Arts and Crafts Movement.

Rookwood Pottery

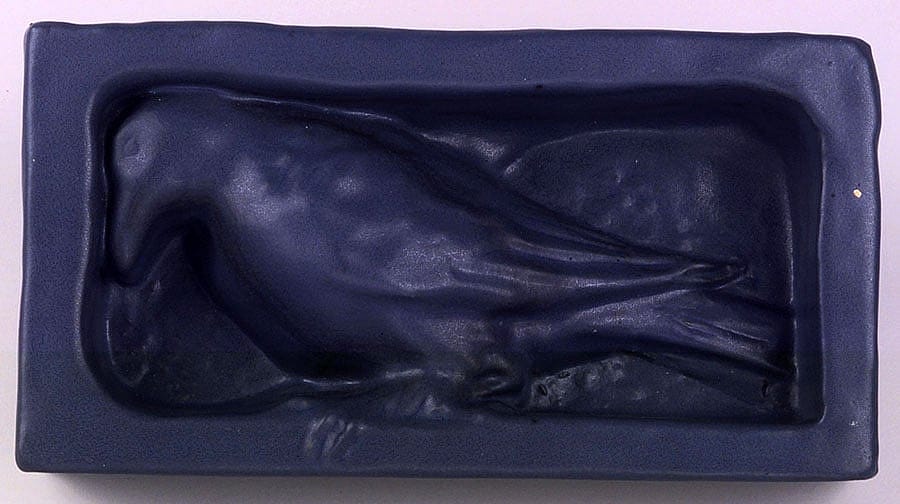

Inside the house, directly above the entry, Sharp placed a sculpture of a large crow, made by Rookwood Pottery of Cincinnati. The crow was hand-modeled in rough, architectural clay, and covered in a matte blue glaze. As a young artist in Cincinnati, he probably became familiar with the company soon after it opened.

Maria Longworth Nichols, a woman from a wealthy Cincinnati family, founded Rookwood in 1880 to produce artistic pottery. She hired local artists as full-time decorators and encouraged the decorators to sign each piece. While Rookwood combined industry and art, the company promoted individual creativity and craftsmanship—central ideas of the Arts and Crafts Movement. Many of Rookwood’s artists received formal training at the Cincinnati Art Academy. When Sharp taught there from 1892 to 1903, several of his students later became Rookwood decorators.

From its founding, the “rook” or crow was the symbol of Rookwood Pottery. Sharp’s Rookwood “rook” symbolized both his past and his present—as a symbol of Rookwood Pottery and Cincinnati, and also as the bird representing the Crow people in Montana.

Roycroft Furniture

Sharp filled the main room of Absarokee Hut with sturdy, handcrafted oak furniture produced by the Roycroft community in East Aurora, New York. Sharp may have met Roycroft’s founder Elbert Hubbard at the 1901 Pan American Exposition in Buffalo, New York. Sharp exhibited a collection of his paintings at the Buffalo Exposition, and possibly visited the nearby Roycroft community in East Aurora.

Hubbard, a charismatic businessman, writer, and lecturer, founded Roycroft in 1895 as a small printing press, which led to a book bindery, and soon expanded into workshops for furniture, metalwork, and stained glass. Roycroft grew into an arts community of more than four hundred workers who learned various crafts through an apprentice system. The well-crafted, solid oak Roycroft furniture followed a simple, Arts and Crafts “mission” style, loosely derived from furniture found in the Spanish Franciscan missions in California.

Like Sharp, Hubbard was fascinated by the American West. According to Roycroft scholar Robert Rust, from 1899 until his death in 1915, Hubbard traveled to the West at least once a year to deliver lectures in Denver. On his western lecture tour in September 1905, he visited the Crow Agency in southern Montana—and crossed paths with Joseph Henry Sharp.

“I helped steer Mr. Hubbard around the reservation for a couple days,” Sharp wrote to Joseph Gest of Cincinnati. “He was very much interested in my work.” They agreed on a trade: Sharp sent several paintings east to Hubbard, and in exchange, Hubbard sent Sharp a collection of superb Roycroft furniture for his Absarokee Hut.

Gustav Stickley and the Craftsman Shops

While Sharp used Roycroft furniture in the main room of the cabin, he also ordered green curtains for the windows and portieres to cover open doorways from Roycroft’s main competitor, the Craftsman Shops, founded by Gustav Stickley in 1898, in Syracuse, New York. By the turn of the century, Stickley’s “mission” style of oak furniture became the primary product of the Craftsman Shops. To promote the philosophy of the Arts and Crafts Movement and the products of his own company, Stickley began publishing Craftsman magazine in 1901. The publication discussed the English roots of the Arts and Crafts Movement, advocated for labor and social reform, and promoted unique American styles of architecture and design.

Once Absarokee Hut was completed, Sharp sent photographs and a letter to the magazine, describing his Arts and Crafts home on the Crow Agency. In June 1906, the Craftsman published excerpts from Sharp’s letter and praised the cabin, proclaiming, “This little house standing alone in the heart of a great western plain is in spirit if not in letter a Craftsman house.”

Sharp, however, neglected to mention that his “Craftsman” home was actually furnished with items from Stickley’s primary competitor, Roycroft. Nonetheless, the Craftsman article applauded Sharp’s simple yet comfortable design. The Craftsman concluded, “It is the building of just such homes as this, born of necessity and finished as a witness to the taste of the owner, that is helping to bring about a reformation in American architecture.”

Living on the Crow Agency

In addition to encouraging good craftsmanship and American design, the Arts and Crafts Movement also promoted the concept that work should be the creative essence of everyday life, rather than just an act of sustenance. When he built Absarokee Hut, Sharp embraced the idea of joining his life with his work. He wrote Craftsman magazine, “We decided that we ought to build a house so that where we were working best we should also live best.”

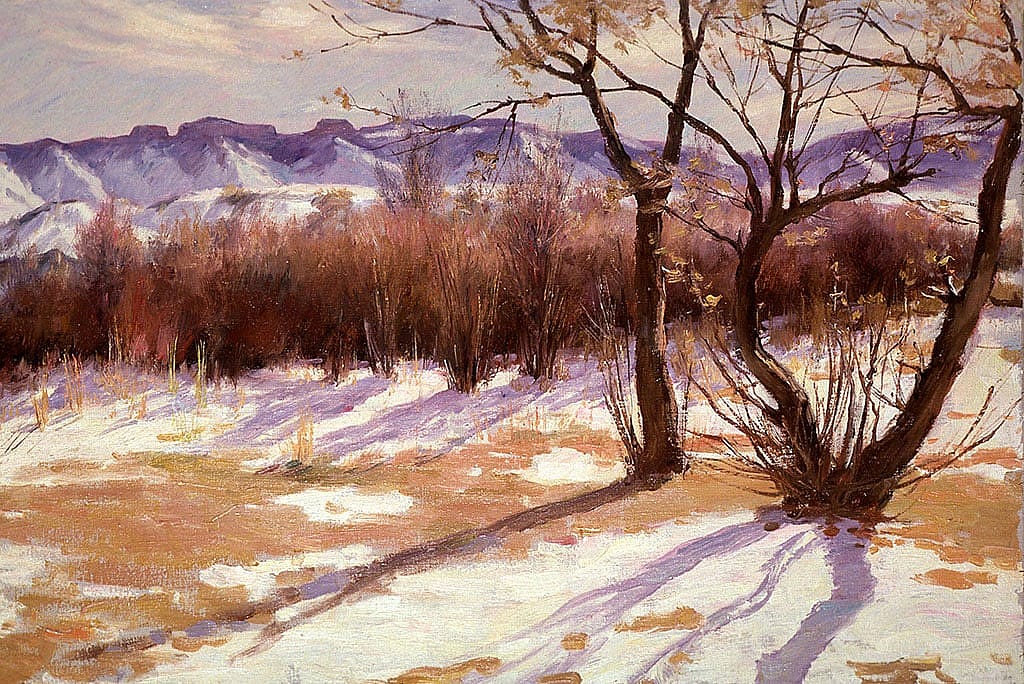

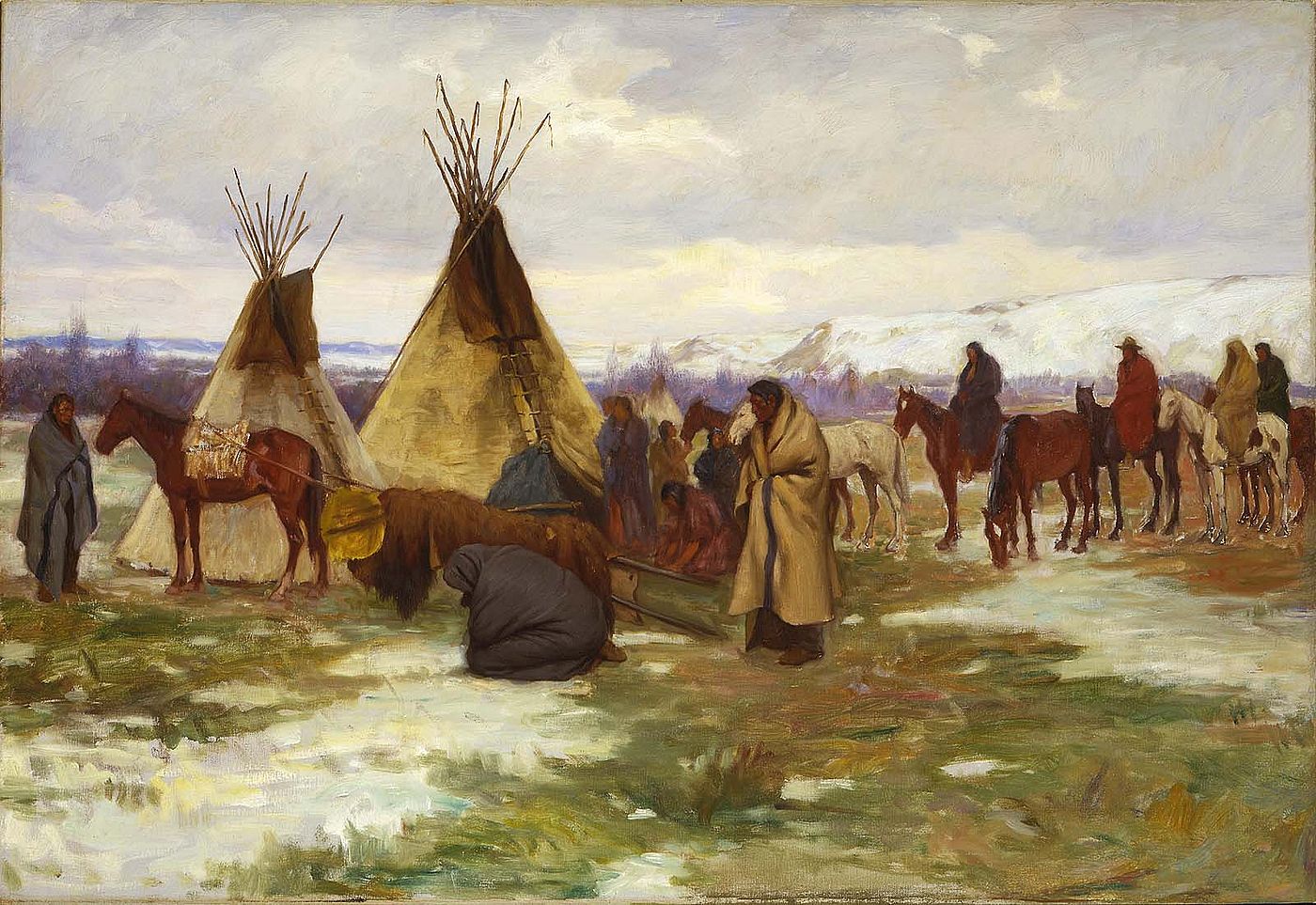

After he finished Absarokee Hut, Sharp could comfortably live in Montana through the winter. His home on the Crow Agency gave him a greater opportunity to paint the people and landscapes of the Northern Plains. While Sharp continued to paint Native American portraits, he experimented with larger compositions and poetic scenes of everyday life on the reservations. Sharp loved the subtle winter colors in Montana, and he endured considerable cold to paint the winter landscape.

From 1905 to 1910, Sharp and his wife Addie spent every fall and winter at Absarokee Hut; in the summer they traveled to Pasadena, California, and Taos, New Mexico. During their years at the Crow Agency, Sharp and Addie gained an increasing respect for Native American traditions. However, as conditions for the Crow people continued to change, Sharp had difficulty finding models for his paintings. By 1910, he changed his primary focus from the Crow Agency in Montana to Taos, New Mexico. He had purchased a home in Taos in 1908, and by 1913 he rented Absarokee Hut to family friends.

Even as Sharp became a founding member of the Taos Society of Artists, he continued to visit the Crow Agency nearly every year until 1920. Sharp brought his collection of Plains Indian objects with him to Taos, and he often reconstructed scenes from Montana by painting the Taos Indians wearing Plains clothing. While his painting career centered in Taos after 1910, Sharp’s experience living in Absarokee Hut remained a lasting influence on his work.

The fully restored Absarokee Hut now stands on the grounds of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, a generous donation from Joseph Henry Sharp scholar Forrest Fenn. In the summer, museum visitors can view the interior of the cabin with many of Sharp’s original Arts and Crafts furnishings.

About the author

Laura Fry worked as the Education and Curatorial Assistant for the Whitney Western Art Museum. She earned a master’s degree in art history from the University of Denver, where she studied the art of the American West with western scholar [and now Center of the West Director Emeritus and Senior Scholar] Peter Hassrick. A Cincinnati native, she wrote her master’s thesis on the early years of Rookwood Pottery. [Since this article was published in 2010, Fry has worked at the Tacoma Museum of Art in Washington, and at the time of this republication in 2018 is the Senior Curator a Curator of Art at Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma.]

All objects and photos are gifts of Mr. and Mrs. Forrest Fenn unless otherwise noted. For suggested reading or a list of references, contact the editor.

Post 185

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.