The Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara People

“A ball of mud was divided between Lone Man and First Creator. They first created a river as a dividing point. First Creator took the west and Lone Man took the east. First Creator made the mountains, hills, coulees, and running streams on the west side of the river. Lone Man made most flat lands with lakes and ponds on the east side. Then they created the four-leggeds, the swimmers of the waters, and those that crawl over the creation, the winged beings of the skies, and finally the two-leggeds. The west side of the Missouri River is rugged and hilly with badlands suited to cattle ranching. The east side has rich, level soil well suited to fields and farming.” -Mandan Origin Story as told by Marilyn Hudson (Hidatsa Tribe)

The Mandan:

The Mandan presently call themselves Nueta, which is translated as “our people.” The Mandan historically lived along the banks of the Missouri River and two of its tributaries—the Heart and Knife Rivers—in present-day North and South Dakota. Speakers of Mandan, a Siouan language, developed permanent settlements and culture in contrast to that of more nomadic tribes in the Great Plains region.

Prior to settling on the Heart and Knife Rivers as early as the seventh century, the Mandan may have migrated from the mid-Mississippi River and Ohio River valleys, then going north towards the Missouri River Valley. The Mandan established permanent villages of large, round, Earth Lodges some 40 feet in diameter arranged around a central ceremonial plaza. The villages were set within naturally defensive features, like ravines or riverbanks, or they built protective walls or ditches.

While the buffalo was essential to the daily life of the Mandan, it was supplemented by agriculture and trade. Women controlled the bountiful gardens that were near the villages, which brimmed with corn, squash, and beans. Corn has always been the mainstay of Mandan agriculture remaining a vital symbol of creation, revitalization, and survival.

The Mandan created trade through the French and Natives of the region serving as middlemen in the market of trading furs, horses, firearms, crops, and buffalo products. In 1804, when Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark and the Corps of Discovery encountered the tribe; the number of Mandan had been greatly reduced by smallpox epidemics and warring bands of Assiniboine, Lakota, and Arikara. (Later they joined with the Arikara in defense against the Lakota.) The nine villages had been consolidated into two. The Lewis and Clark expedition met with such hospitality in the Upper Missouri River villages that the expedition wintered over. In honor of their hosts, the expedition dubbed the settlement they constructed Fort Mandan. It was here that Lewis and Clark first met Sacagawea, a Shoshone woman who had been captured. Sacagawea assisted the expedition with information and translating skills as they traveled westward towards the Pacific Ocean. Upon their return to the Mandan villages, Lewis and Clark took the Mandan Chief Sheheke (Coyote or Big White) with them to Washington to meet with President Thomas Jefferson. In 1812, Sheheke was killed in battle.

American artist George Catlin visited the Mandan near Fort Clark in 1833; drawing and painting portraits and scenes of Mandan life. His skill at portrayal so impressed MatóTópe, that he invited Catlin as the first Euro-American to be allowed to watch the Okipa ceremony, an intricate series of rites linking all of creation to seasonal conditions. As part of the earth-renewal practices, the Okipa emphasized the renewal of game animals in the Buffalo Dance ceremonies. The winter months of 1833 and 1834 brought Prince Maximilian of Wied-Neuwied and the Swiss artist Karl Bodmer to stay with the Mandan. Bodmer made detailed sketches and paintings of the cultures, dress, and appearance of the Mandan and their allies, which are still used today as references for scholars. Bodmer and Catlin documented the Upper Missouri River cultures in their peak, just before they were devastated by disease.

In June 1837, an American Fur Company steamboat traveled westward up the Missouri River from St. Louis. Its passengers and traders aboard infected the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara tribes. There were approximately 1,600 Mandan living in the two villages at that time. The disease effectively destroyed the Mandan settlements. The thirteen clans were reduced to two divisions. Almost all the tribal members, including MatóTópe, died. Estimates of the number of survivors vary from only 27 individuals to up to 150, though most sources usually give the number at 125. The survivors banded together with the nearby Hidatsa in 1845 and created Like-a-Fishhook Village.

The Hidatsa:

The Hidatsa are made up of three closely related bands: the Hidatsa Proper, the Awatixa, and the Awaxawi. The Hidatsa Proper call themselves Hiraacá—traditionally thought to mean “willow.” Having originally lived in the Devil’s Lake region in what is now eastern North Dakota, by the early 1600s, the Hidatsa had moved to settle along the Missouri River in west-central North Dakota—near the Mandan. The two tribes were usually on good terms, both speaking Siouan dialects, although the languages were not mutually intelligible. The Hidatsa lived near the junction of the Knife and Missouri Rivers, about sixty miles up from the Mandan.

The Hidatsa lived in substantial earth-covered lodges clustered in villages of several hundred to more than a thousand individuals. These stable communities were perched on the rims of terraces overlooking the Missouri River floodplains. In the lowlands, the Hidatsa grew bountiful gardens of corn, beans, squash, and sunflowers all owned and tended to by the women, while the men hunted white-tailed deer and other woodland animals. Behind the villages were the river bluffs that separated the valley from the rolling, upland plains, where they hunted pronghorn and the massive herds of buffalo. The products produced denoted the Hidatsa villages as major part of the ancient Indigenous trading center of the Plains—and later when the Euro-Americans arrived.

Hidatsa society is matrilineal—meaning descent is traced from the mother’s side of the family. Hidatsa says that a person comes into the world through their mother’s clan, and leaves through their father’s clan. Meaning that the mother’s clan bestows membership and belonging; while the father’s clan gives them distinct rights and responsibilities. The clan structure arranged an individual’s participation in life events and ceremonies.

After a smallpox epidemic in 1781, the Mandan moved upriver to live near the Hidatsa, as their numbers had been so reduced, they were no longer able to defend their villages. Farther downriver, near the mouth of the Grand River, lived the Arikara, the third group of Earth lodge dwelling Natives. Although they spoke a different language (being related to the Pawnee of Nebraska), their villages and way of life were much the same as those of the Hidatsa and Mandan. The Hidatsa also maintained relationships with their relatives to the west, the Crow.

The American artist George Catlin visited the tribes in 1832 and remained with them for several months in 1832. In 1833 – 1834, the Swiss artist Karl Bodmer, traveling with German explorer Prince Maximilian zu Wied-Neuwied, drew and painted the clothing and people and cultures of the villages.

Both Catlin and Bodmer’s artworks recorded the Hidatsa and Mandan societies, that where were rapidly changing under pressure from encroaching settlers, infectious disease, and government restraints. After an 1834 attack by the Dakota and the 1837 smallpox epidemic that reduced the Hidatsa to about 500 people, the three groups merged with the Mandan at Like-a-Fishhook Village in 1845. The Arikaras joined them in 1856. Further reading: A Living Tradition: Plains Indian Food and Medicine.

The Arikara:

The Arikaras, who call themselves Sahnish, migrated from present-day eastern Texas and nearby parts of Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Louisiana to the central Plains (ca. 1400), primarily now Nebraska. This is where their earth lodge development and agricultural knowledge of corn developed. Later they moved further north to build villages on the Grand and Cannonball Rivers in what is now northern South Dakota. In the 1700s, the Arikaras controlled land along the Missouri River for one hundred miles. Arikaras are closely related to the Skiri Pawnees; they split when both groups were settled on the Loup River in Nebraska. Both groups share linguistic characteristics of the Caddoan language family—but the Pawnee and Arikara languages are not mutually understandable.

The Arikara were farmers, raising corn, beans, tobacco, and squash both for food and to trade with other tribes in the area. Like the Hidatsa, the women worked and owned the gardens. Corn was such an important staple of Arikara society that is was referred to as “Mother Corn.” The Mother Corn Ceremony centered on the theme of world renewal and linked the universe through Mother Corn (represented by a cedar tree) to the keepers of sacred bundles and their kin. In everyday life, Mother Corn instructed the people in the right ways of living in the world. They also had seasonal buffalo hunts, tracking the herds while utilizing easily portable tipis. Their agricultural success also balanced the power with the non-farming Lakota, neighbors who traded for the commodities the Arikara produced.

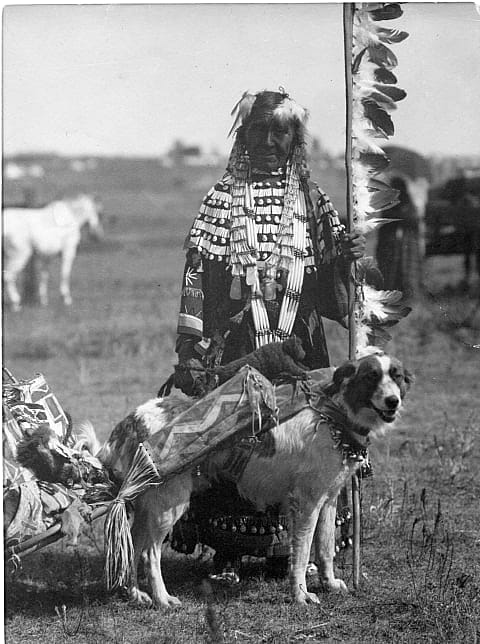

Traditionally an Arikara family owned 30–40 dogs. The people used them for hunting and as sentries, but most importantly for transportation, before Plains tribes adopted the horse. Many of the Plains tribes had shared the use of the travois, a transportation device to be pulled by dogs. It consisted of two long poles attached by a harness at the dog’s shoulders, with the butt ends dragging behind the animal; midway, a ladder-like frame of hide strips was stretched between the poles; it held loads that might exceed 60 pounds. Women used dog-pulled travois to haul firewood or infants. These were also used for meat transport during the seasonal hunts; a single dog could pull a quarter of a buffalo. The introduction of the horse in the mid-18th century changed everything, from transportation to hunting and warfare.

The Arikara War took place in August 1823 between the United States and the Arikara Nation near the Missouri River in present-day South Dakota. Arikara warriors had previously attacked General Ashley’s fur trading expedition traveling to the Yellowstone (Elk) River to establish trade. The U.S. responded with 230 soldiers, 750 Sioux warriors and 50 of Ashley’s trappers, all under the command of Col. Henry Leavenworth. This conflict was the first United States military conflict with Western Native people and set the tone for future American encounters between the Crow and Blackfeet further to the west.

In June 1833, the American artist George Catlin passed the Sahnish villages at the Grand River but did not go ashore because he considered them “hostile.” That same year, the Arikara left the banks of the Missouri River after two successive crop failures and conflicts with the Mandan. They rejoined the Pawnees for three winters at the Loup River. However, this location made them susceptible to attack by Euro-Americans and the Lakota, causing a move back to the Missouri River region.

In June 1837, an American Fur Company steamboat traveled westward up the Missouri River from St. Louis. Its passengers and traders aboard infected the Arikara, Mandan, and Hidatsa tribes with the third smallpox outbreak in the region. The tribe was decimated. In 1856, a fourth smallpox outbreak occurred in the Star Village at Beaver Creek (across from Fort Berthold). This last outbreak and the constant raids by the Lakota forced the move of some Arikara to Like-a-Fishhook village near Fort Berthold, but some did remain at Star Village.

In 1862, the Arikara joined the Hidatsa and Mandan at Like-a-Fishhook Village in what is now North Dakota. For work, many Arikara and Crow men scouted for the U.S. Army at nearby Fort Stevenson against their traditional enemies the Sioux. In 1874, the Arikara guided the Army on the Black Hills Expedition. The Arikara Scouts were also present at the 1876 Little Big Horn Expedition with Geo. A. Custer.

By the time of the Corps of Discovery in 1803, smallpox epidemics, that had also affected the Mandan and Hidatsa, reduced the Arikara population to approximately 2,000 living in three smaller villages in 60 earth lodges on an island in the Grand River. The Corps stayed at the Arikara villages for five days, discussing trade issues and the possibilities of Arikara peace with the Mandan and Hidatsa. The Arikara agreed to consider peace with the tribes to the north.

Contemporary People:

The Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara—the Three Affiliated Tribes—share the Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota. By the second half of the nineteenth century, the holdings of the Three Affiliated Tribes gradually decreased. Going from 12 million acres in 1851 established under the Fort Laramie Treaty to 8 million acres as the Fort Berthold Reservation in 1870. By 1910 it was down to 900,000 acres.

In 1951, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began construction of Garrison Dam on the Missouri River. This dam created Lake Sakakawea, which flooded portions of the Fort Berthold Reservation including the villages of Fort Berthold and Elbowoods as well as several other villages. The former residents of these villages were moved and New Town was established. The Mandan, Arikara, and Hidatsa had many losses of their hereditary land area. The Garrison Dam impacted the tribes, having been compared as to being equal in its severity as the 1837 smallpox epidemic that nearly reduced the tribes to cultural extinction. The flooding claimed approximately one-quarter of the reservations land. It not only flooded and destroyed the fertile bottomlands they farmed, but it also fractured the communities separating them across wide distances. In addition, the flooding claimed the sites of historic villages and archaeological sites. While New Town was constructed for the displaced tribal members, much damage was done to the social and economic foundations of the reservation. Once nearby neighbors, they were now surrounded by immense lakes cutting them off from one another. This story is told in Earth Lodge exhibition in the Plains Indian Museum.

Today the Three Affiliated Tribes are an united sovereignty and about half of the members still, reside in the area of the reservation. The heart of the Mandan community is Twin Buttes. The Hidatsa have their distinct communities at Shell Creek and Mandaree. The Hidatsa are emphasizing the need to retain Native speakers of their language through projects like the Hidatsa Language Program at Mandaree, and through their website. Around 6,300 people live on the Fort Berthold Reservation, and there are over 12,000 enrolled members of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation today.

This text was originally published with research done by scholar Anne Marie Shriver of the Paul Dyck Buffalo Culture Collection. Hunter Old Elk is the editor but not the original author.

Written By

Hunter Old Elk

Hunter Old Elk (Crow & Yakama) of the Plains Indian Museum at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, grew up on the Crow Indian Reservation in Southeastern Montana. Old Elk earned a bachelor's degree in art with a focus on Native American history at Mount St. Mary’s University in Maryland. Old Elk uses museum engagement through object curation, exhibition development, social media, and education to explore the complexities of historic and contemporary Indigenous culture. She is especially inspired by the stories of Native American women who lived and thrived on the Plains. Facebook/ Instagram: @plainsindianmuseum