A Living Tradition: Plains Indian Food and Medicine – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Fall/Winter 2018

A Living Tradition: Plains Indian Food and Medicine

By Hunter Old Elk & Liz Bowers

“Whatever type of healer you become, remember this truth: There can be no healing without heartfelt love and compassion for the person to be healed.” — Alma Snell (Crow Nation), Montana

When one hears the phrase “Plains Indian,” it is very likely that he or she immediately thinks of brightly colored adornment such as clothing, bonnets, and horse decoration, or cultural activities such as buffalo hunts, warfare, and nomadic tipi camps. While these are certainly a part of the tribal history and culture of many Plains Indian tribes, there is a much lesser known culture: the agrarian or gardening culture of tribes such as the Hidatsa, Mandan, and Arikara (the Three Affiliated Tribes), and the foraging activities of other nomadic groups.

The Three Affiliated Tribes cultivated intricate gardens to provide food for their families alongside hunting buffalo and other game, but they were not nomadic as one might expect. They lived in great earth lodges, rarely moving their villages. The Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara settled along the Knife River, in what is present-day North Dakota, until about 1839 when white traders brought a smallpox epidemic that wiped out more than half of each tribe.

Banding together, the tribes eventually moved closer to the Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota where the United States government attempted to enforce the individual allotment of land instead of the communal agrarian style they traditionally held. In those days, researchers studying Native cultures were convinced that the Native way of life was becoming extinct as the tribes assimilated into white culture. For this reason, they gathered immense amounts of anthropological and material culture data to preserve the Native knowledge for future generations.

Buffalo Bird Woman

In 1906, the anthropologist Dr. Gilbert L. Wilson (1868–1930) met with the Hidatsa Maxi’diwiac, otherwise known as Buffalo Bird Woman (ca. 1839–1932), and her son Edward Goodbird who served as translator. From their village along the Knife River to Like a Fishhook village, she described in intricate detail how her family prepared, planted, cared for, and harvested their garden.

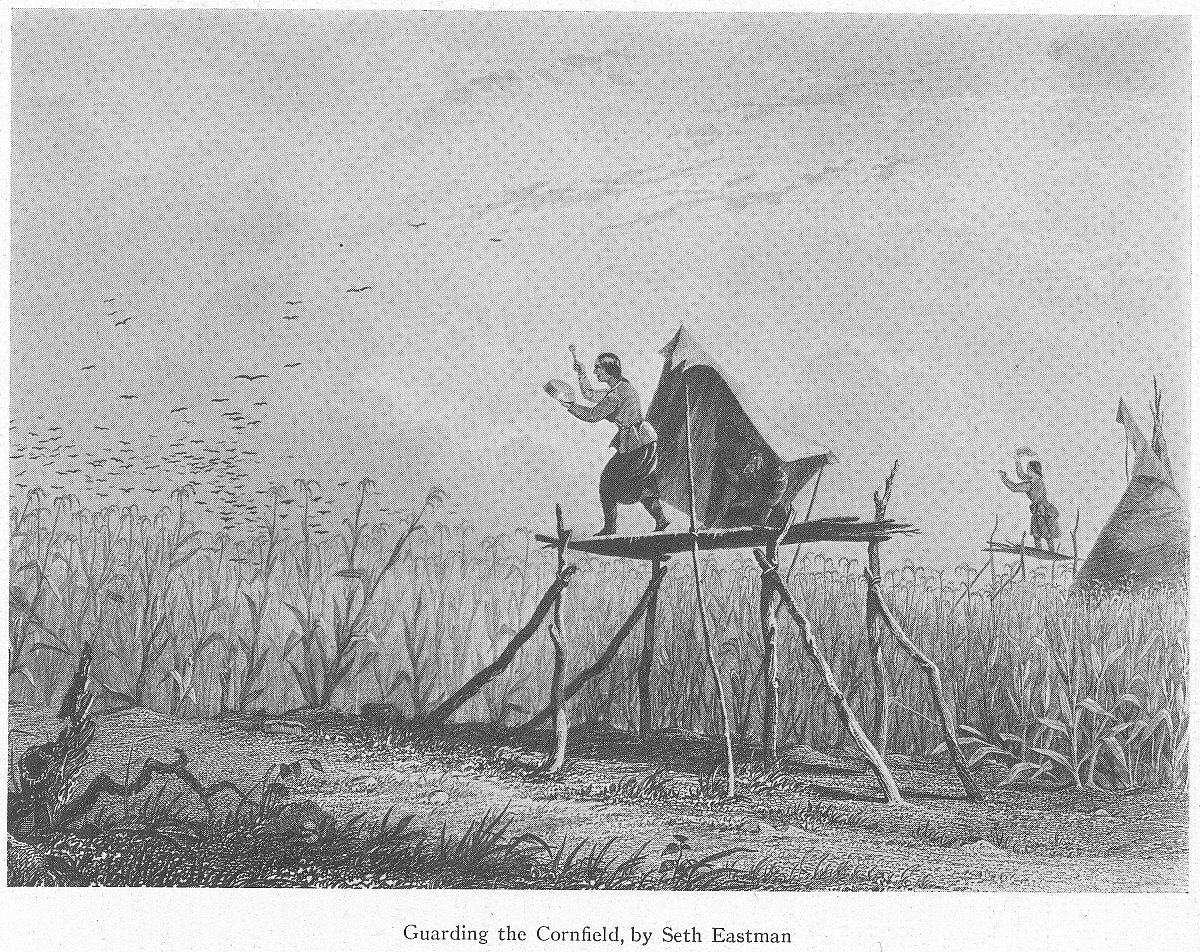

Watching the change of the seasons, the gardeners knew exactly when it was time to begin their planting. Starting with sunflowers in April, the women would later plant corn, squash, and beans from May to mid-June. The women of Buffalo Bird Woman’s village guarded their gardens zealously, building a watcher’s stage at one end of the garden where they would watch over the field, scaring away birds, other animals, and boys who would try to steal the corn. The women sang love songs teasing the boys who came to their fields, but they did not speak to the boys unless they were family.

In August, when the time came to harvest the ripe corn, the family would organize a corn-husking feast, taking a meal of buffalo meat to the field for the young men who came to help them. Young men would especially come out to help in the gardens of their sweethearts. Whether sunflower seeds, corn, squash, or beans, every plant was harvested with love and preserved to last the family through the winter.

Nomadic Tribes: Living With the Land

Nomadic tribes, like the Flathead (Montana) and Crow (Yellowstone River Valley), also used plants as a great source of food and medicine. However, unlike the Hidatsa, Mandan, and Arikara tribes, the nomadic cultures did not rely on permanent gardens. Instead, they would gather what the earth provided in each season. The women, midwives, herbalists, and healers of the tribes gathered berries, nuts, roots, and herbs as the plants were ready to harvest.

Some of these plants were more sacred than others, and each had to be gathered in its own specific way. The gatherers would also have to know which part of the plant was useful to them and which varieties were unsafe to consume. Common plants gathered by these tribes include yarrow, bear root, echinacea, arrow leaf balsamroot, and wild berries such as chokecherries, buffalo berries, and wild plums. Over time, the gatherers also adapted to what was available around them. For example, they began gathering dandelions to use in salads and medicine poultices in the same way they used yarrow. Dandelions were not native to the plains but were brought to the area by white traders and settlers.

The Plains Indians adapted to their changing environment and found what was useful in it. Where Buffalo Bird Woman’s people exchanged bone hoes for those made of iron, the nomadic tribes learned to gather new food and medicine resources. In the mid-twentieth century, these practices and adaptations continued to thrive. Alma Snell (1923–2008) of the Crow Nation in Montana dictated in detail the cultural heritage of how she was taught to use the plants all around her for food and medicine in her daily life. As a healer, she continued to gather the natural remedies that others had shown her. For instance, yarrow is used externally to ease the pain of bites and stings, heal wounds, soothe burns, and stop bleeding. Used internally it supports urinary tract health, is good for the liver, calms the stomach, and cleanses the kidney and prostate. Bear root helps with birthing and menstrual flow and pain and alleviates toothaches, arthritis, sore throats, respiratory problems, and spider bites.

Sometimes, one person or another would call Snell after seeing the doctor. They disliked what the doctor suggested they do to get better, and hoped that Snell would have a better solution. Instead, however, she taught them to obey, saying, “Most of the time doctors know what they are doing, and besides, there is power in obedience. When your doctor or nurse advises you about what to do and what not to do, stick to it. Be obedient. Obedience is power. It will make you healthy. It will make you happy. Maybe it will make you better. Listen. Be obedient.”

The twenty-first century has found a new trend in searching for natural remedies and foods. This makes it all the more important that we understand and honor the traditional history and culture of food and medicine of the Plains Nations.

A Living Tradition

Still today, landscape and food are concepts synonymous with Indigenous identity for First Nation groups of Canada, Alaska Natives, and Native Americans. Individuals in these groups maintain cultural knowledge of their food systems and medicinal needs. For thousands of years, tribes of the Great Plains and the Northwest Plateau depended on hunting, fishing, and foraging of tribal territories. These cultural activities provided nourishment and spiritual health.

In contemporary culture, groups in the Plains such as the Lakota, Nakota, Dakota, Crow, Cheyenne, Blackfeet, Arapaho, and Shoshones rely on their protected rights to hunt and fish in their tribal homelands. With the seasons, these groups also forage for flora such as wild turnips, bitterroot, onions, and berries, as well as plants used in ceremonies like sacred tobacco, sweetgrass, bear root, cedar, sage, and mint. Southern Plains groups, such as the Omaha and the Cherokee, cultivate and collect Native seeds to garden corn, squash, lentils, and wildflowers. Plateau tribes— Yakama, Cayuse, Salish, Kootenai, Nez Perce, and the Warm Springs bands, etc.—depend on hunting, foraging, and salmon and steelhead fishing to ensure sustainability.

Health Disparities in Native Communities

![2016 USDA map. According to the Medley [Florida] Food Desert Project, Florida International University Department of Biological Sciences, nearly 24 million Americans live in food deserts. The map presents percentages of people without cars living in areas with no supermarket within a mile.](https://centerofthewest.org/cdn-cgi/image/width=1034,height=556,fit=crop,quality=80,scq=60,gravity=auto,sharpen=1,metadata=none,format=auto,onerror=redirect/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/08-Food-desert-map.png)

Currently, tribes in the United States and Canada combat “food deserts” and poverty in their communities by enforcing their food sovereignty efforts. Food deserts are low-income communities which lack access to healthy and affordable foods because of distance and lack of transportation. Indigenous food sovereignty is the process by which communities address health issues and access to nourishment through culturally responsive action and the reintroduction to traditional food systems.

Native Americans, Alaska Natives, and Canada First Nations people are twice as likely as non-Natives to develop diabetes and kidney failure from diet. Other alarming issues in these communities are the associated factors of obesity and mental health. The reasoning points to a lack of access to whole foods and other food insecurities in Native communities. Often, poverty is the underlying issue for citizens who reside on reservations and reserves. Recognizing a call to action, government agencies and non-profit groups seeking to alleviate many of the factors that result in food insecurity. The government puts aside monies for food distribution programs and childhood intervention programs on reservations. Non-profit programs and activists also have a call to action which directly supports Indigenous food sovereignty.

Using traditional knowledge, environmentalism, and conservation efforts, groups such as Native American Food Sovereignty Alliance (NAFSA), Native Food Systems Resource Center of Canada, and Intertribal Agriculture Council supports and develops Indigenous food practices and policies to combat food insecurities. Their strategies support cultural identity through health, spirituality, economics, and connections to the natural world as a means of sustainable tribal growth.

From the Roots of the People

Today, there are many individuals working tirelessly to maintain tribal culture as they pursue sustainability in providing for the health and well-being of their citizens. As examples, we highlight the work of four people, each with a story that demonstrates their commitment to the very roots of their Native culture.

Winona LaDuke

Winona’s Hemp and Heritage. Winona LaDuke (Anishinaabe, White Earth Ojibwe) received her BA in economics from Harvard University in 1982, followed by an MA in community economic development from Antioch University. LaDuke has a long career in environmentalism and policymaking. She is the Program Director of Honor the Earth, a Native environmental advocacy organization focusing on climate change, renewable energy, sustainable development, food systems, and environmental justice.

LaDuke is currently pursuing a personal project called Winona’s Hemp and Heritage to grow hemp in the state of Minnesota. Her goal is to use hemp fibers in commercial clothing production to reduce synthetic materials and synthetic waste. winonashemp.com

Dr. Rosalyn LaPier

Plants That Purify. Dr. Rosalyn LaPier (Blackfeet) is an award-winning Indigenous writer and ethnobotanist (one who studies how people of a particular culture and region make use of native plants) with a BA in physics and a PhD in environmental history. She is an associate professor of environmental studies at the University of Montana. LaPier studies the intersection of traditional ecological knowledge learned from elders, with the academic study of environmental history

She gained her ethnobotany education from her maternal grandmother, Annie Mad Plume Wall, and her aunt Theresa Still Smoking. LaPier is the author of several books on Blackfeet history and is currently working on a new book, Plants that Purify: The Natural and Supernatural History of Smudging. The volume is a study of traditional Blackfeet women and their use of plants in ceremony. www.rosalynlapier.com

Sean Sherman

The Sioux Chef. Sean Sherman (Oglala Lakota) is the Founder and CEO Chef of The Sioux Chef based in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His goal is to revitalize Native American Cuisine through a modern Indigenous lens. Sherman has an extensive career of more than thirty years cooking across the United States. His culinary passion is the revitalization and awareness of Native food systems. In his practice, he uses traditional Native knowledge, regional and seasonal access to foods, land stewardship through hunting and fishing, foraging, natural salt and sugar making, and food preservation to create meals decolonized of global influence.

The Sioux Chef is a team of indigenous chefs from the Anishinaabe, Dakota, Navajo, Northern Cheyenne, Oglala Lakota, and Dakota tribes. They are also intentional about purchasing from Indigenous food producers and other sustainable partners in their catering business and food educator efforts—and soon in their new restaurant. Their cookbook, The Sioux Chef’s Indigenous Kitchen, is available online at Sioux-chef.com

Taylor Keen

Sacred Seed. Taylor Keen (Omaha/ Cherokee) is the founder of Sacred Seed and is a business instructor at Creighton University in Omaha, Nebraska. He is also an active member of the Plains Indian Museum Advisory Board at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. His work combines traditional knowledge and ceremonial practices of the biological cultures of the Omaha and Cherokee with modern conservation efforts.

Sacred Seed is a non-profit organization based in Omaha whose aim is to collect, grow, and preserve ancestral seeds native to the Plains. Keen’s group grows genetically diverse seeds of corn, squash, beans, and sunflowers, also known as the “four sisters.” Keen envisions an Indian Country planting in traditional ways and using the biological knowledge to achieve sustainability and cultural preservation.

These are but a few examples of the many who preserve the living tradition of hunting, gathering, and gardening cultural methods for food and medicine—all of which continue to be an important part of Indigenous life today.

Hunter Old Elk (Crow/Yakama) of the Plains Indian Museum at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West holds a bachelor’s degree in art (with a focus on Native American history) from Mount St. Mary’s University, Emmitsburg, Maryland. Old Elk assists Curator Rebecca West in object curation and exhibition development. She uses museum engagement through research and social media to explore the complexities of historic and contemporary Indigenous cultures.

Elizabeth Bowers, Social Media Specialist at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, is a senior at the University of Wyoming with a focus in communications. Bowers studies the interactions of audiences and the content they engage with online. Through the Public Relations Department, she presents this content to Center of the West audiences, inviting them to engage with museum collections and the cultures they represent.

Written By

Hunter Old Elk

Hunter Old Elk (Crow & Yakama) of the Plains Indian Museum at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, grew up on the Crow Indian Reservation in Southeastern Montana. Old Elk earned a bachelor's degree in art with a focus on Native American history at Mount St. Mary’s University in Maryland. Old Elk uses museum engagement through object curation, exhibition development, social media, and education to explore the complexities of historic and contemporary Indigenous culture. She is especially inspired by the stories of Native American women who lived and thrived on the Plains. Facebook/ Instagram: @plainsindianmuseum