Originally published in Points West magazine

Spring 2015

A Leap But Not a Stretch: Buffalo Bill and La Rana nel Wild West, Part 1

By Mary Robinson & Robert W. Rydell

Close your eyes and imagine a typical poster or illustration of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. What comes to mind? Is it Buffalo Bill’s silhouette on a charging bison with the announcement, “Je Viens”? Or is it perhaps a colorful poster that advertises the Congress of Rough Riders and the reenactments of battles between cowboys and Indians set against landscapes of magnificent prairies and mountains?

Our bet is that as you conjure up these images, you are unlikely to have in your memory bank the image that stopped us in our tracks—a lithograph that hangs in the Buffalo Bill Museum. It was originally produced on the occasion of Buffalo Bill’s one-night appearance in Bologna, Italy, on April 8, 1906, for an Italian magazine called La Rana (The Bullfrog). The lithograph, La Rana nel Wild West (The Bullfrog in the Wild West) does indeed depict Buffalo Bill riding, of all things, a bucking bullfrog…

Yes, a bucking bullfrog! Look carefully at the illustration. It is, to say the least, curious. Leave aside the Italian words around the borders for a moment and look at the color of Buffalo Bill’s boots! Are they really lapis lazuli? And look at those playful brush strokes that produce a decorative palette of oblong shapes. Is this really Buffalo Bill (and a frog) done up in the art nouveau style? And is that kicking bullfrog really larger than Cody himself?

What’s more: Why was this image created? Who was the artist? And, how on earth did this lithograph find its way to the Buffalo Bill Museum?

These are serious questions, and never mind any impulse you might have to make jokes about Hopalong Cassidy, at least until we get to the end of our story. Leave the jokes to us or, better yet, to La Rana—the Giornale Umoristico Politico, or Journal of Political Humor—that commissioned the artist, Mario Cetto, to produce this lithograph to advertise its special issue dedicated to the Wild West’s appearance in Bologna, Italy.

All kidding aside, we still have many unresolved questions about this image and how best to understand it. We hope you will have some suggestions for us as we continue our quest to learn about it. At this stage, we thought we would share with you how our curiosity about this illustration led us on a fascinating journey that has taken us full circle, from the Buffalo Bill Museum and the McCracken Research Library to Buffalo Bill’s one-night-stand in Bologna (and into the maelstrom of Italian politics)—and then home again.

From Italy, our investigation led us, surprisingly, to England and Highclere Castle (yes, you know it from the PBS series as Downton Abbey), and from there back to the Buffalo Bill Center of the West where we have made a small but important change on a label. More significantly, we developed some new insights into the complex ways audiences received the Wild West in Europe.

La Rana Nel Wild West

The lithograph, La Rana Nel Wild West, is as irresistible and delightful as any Buffalo Bill’s Wild West poster in the museum. It seldom fails to draw smiles from our visitors, in spite of the puzzling, not to say bizarre, juxtaposition of Buffalo Bill and a green frog. Here we have a caricaturist taking liberties that a commercial lithographer would scarcely attempt. At the same time, we recognize a visual gag, however much it mystifies and leaves us on the outside of an in-joke. We chuckle at the image, but we want to know more!!

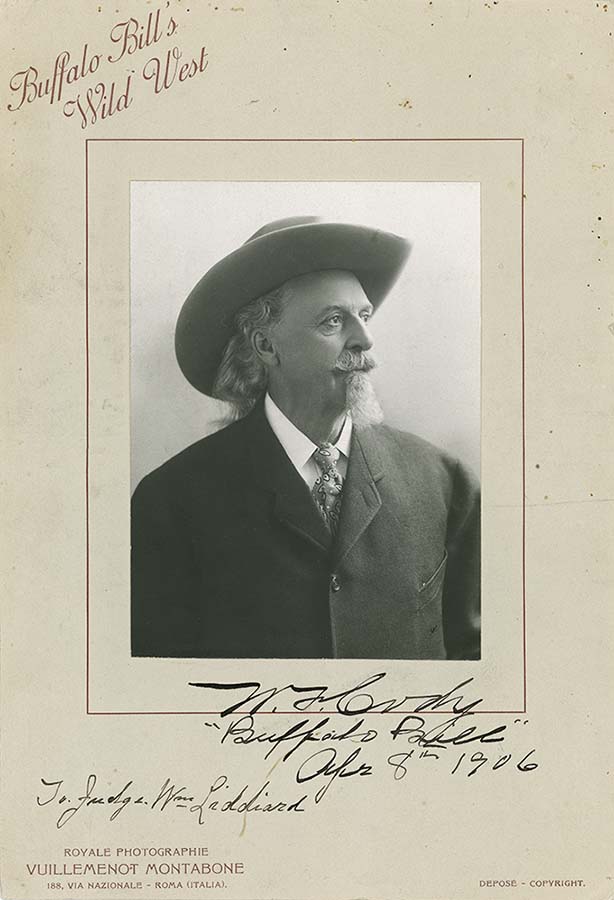

The original owner of the poster, as we shall see, believed it was an advertisement for the Wild West. A closer look reveals it to be a creature of a different color. Buffalo Bill soars into the air on the back of a frog the size of a bucking bronco. The frog springs forward, yellow eye bulging and green toes outspread. The athletic showman grips the reins in one hand while he doffs his hat stylishly with the other. Though Buffalo Bill is unidentified on the poster, people across Italy would have easily recognized his thigh-high boots, buckskin jacket, grey curls, and goatee. The Wild West had famously toured the country in 1890 and was back in 1906 for a farewell run. Between March and May of that year, the show would appear in thirty-four Italian cities and towns.

The image of an American riding a frog had immediate, comical resonance to Italians, who recalled a familiar caricature of Mark Twain astride an amphibious steed. The popular humorist had toured Europe in recent decades and was widely known for his famous story of the Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County (1865). This association of man and frog, then, recalled Twain’s signature irreverence and signaled what was in store for readers of La Rana. The poster artist who signed the piece, Mario Cetto, is largely lost to history, but he created an image that a Bolognese would have appreciated at a gleeful glance. The frog in the Wild West is coming! The issue of La Rana devoted to the Wild West should not be missed! In this case, Twain’s “innocent abroad” may well have been Buffalo Bill himself riding into the waters of European politics.

La Rana

Our first task in interpreting the poster was to understand the genre of the publication to which it refers. The Museo della Satira in Forte dei Marmi provided the following reply to our inquiry:

La Rana was established as a weekly publication in 1865 after the abolition of papal censorship and was one of many anticlerical and satirical magazines of the day. Edited by Leonida Gionetti and Augusto Grossi, the magazine consisted of four pages containing stories, riddles, charades, and little poems. After 1876, it featured a large, central lithographic page in bold color. One could find the most striking of these lithographs displayed on the walls of living rooms and cafés in Bologna.

La Rana thrived during a period of political transformation and often caricatured politicians carrying out clumsy and destructive reforms. Significantly, “the frog,” carries with it another meaning in the Bolognese vernacular. For this information, we are indebted to Dr. Cristian Della Coletta at the University of Virginia, who informed us that “la rana” connotes being “broke, poor, or bankrupt.” Daniela Schiavina, a librarian at the Museum della Citta di Bologna, added her observation that, across much of Italy, the color green is associated with lacking money.

This color-coded frog, in short, was a voice for the underclass in Italy. Addressing serious economic issues, and with political sympathies for the victims of heavy-handed and incompetent leadership, La Rana spoke for the dispossessed who had not shared in the benefits of the modern industrial state. La Rana croaked loudly for a more liberal and stable government during the tumultuous decades leading up to World War I.

According to The Oxford History of Italy, Italy had been, until the mid-nineteenth century, an “untidy mosaic of dynastic principalities.” Unification was the goal of the decades before 1900, a movement known as “Risorgimento” that tried to achieve a modern state.

In spite of this effort, many areas of the country were impoverished and backward compared to the rest of Europe. The Austro-Hungarian Empire controlled territories in the north, areas characterized by a social and political culture very different from southern Italy and Sicily. Victor Emmanuel III held sway over a weak, constitutional monarchy in 1906. The vulnerabilities of the state would prove disastrous in World War I and lead to the rise of fascism in the decades that followed. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West arrived in Bologna in a political culture rife with social and economic tensions.

Hunting the Frog: Off to Denver and Italy

To locate the issue of La Rana which the poster advertises proved a quest as amusing and filled with surprises as the poster itself. Online searching, including heroic efforts by Mary Guthmiller, interlibrary loan specialist at Montana State University, turned up only scattered issues of the publication in American libraries. Fortunately, former Buffalo Bill Museum Curator Dr. Paul Fees had found the poster fascinating and had gone frog hunting himself. He discovered the April 6, 1906, issue of La Rana at the Denver Public Library in the archive related to William F. Cody. We examined Dr. Fees’s notes in a collection file in our museum registrar’s office; with these interesting clues in hand, we traveled to the Denver library and photographed the issue.

Denver’s copy of La Rana remains in fair condition. The pages are larger than a typical American magazine and resemble a newspaper with all the creases and tears we would expect from a 108-year-old publication. The colorful lithographs are wonderfully preserved and appear to be of a piece with the art nouveau style of the poster. An internal page devoted to advertisements helped us translate the reference on the poster: The Bologna firm of A. Noe (perhaps Arca di Noe, literally “Noah’s Ark”) specialized in printing and chromolithography.

Beyond the language barrier, it was evident that the magazine’s riddling style of commentary would prove difficult to interpret without close translation and study of Italian politics in 1906. Fortunately, scholars associated with the Papers of William F. Cody assisted us in this effort. Graduate student Alessandra Magrin traveled in Italy for her studies, seeking publications related to Buffalo Bill’s Wild West tours. She located bound volumes of La Rana in the Biblioteca dell’ Archiginnasio in Bologna and forwarded digital images of a superior quality to those we had produced in Denver. Then, we placed these text images before several Italian-speaking contacts. Papers Associate Editor Dr. Julia Stetler translated two longer pieces with significant Buffalo Bill-related content. The first was a mock interview with the showman, which had appeared in the March 30-31 issue, and the other was a poem titled “The Arrival of Buffalo Bill.”

These translations, together with the lithographs, shine light into the murky political waters in which La Rana once swam. Cody and his Wild West show Indians provide the metaphor for an uneasy power relationship between the conservative leadership and the socialists, who had been an organized party in Italy for several decades. In the cover cartoon, Buffalo Bill is at the far right, gesturing toward a group of mounted Indians wearing headdresses—the chief of whom the artist identifies as Ferri, a prominent member of the revolutionary wing of the socialist party. To the left, dressed as Buffalo Bill and sitting stiffly on his white horse, appears the conservative Prime Minister, Sidney Sonnino. The caption reads “The New Troupe of Buffalo Bill,” and Cody himself declares, “Sirs, I have the honor to present those who will succeed me.” In other words, this group of performers is the next “circus” expected in town.

Enrico Ferri holds a red flag, and it is no coincidence that the “redskins” identified as Turati, Costa, and others, are socialists. In fact, Filippo Turati had founded the party, and the placement of Ferri at the front may call attention to internal party divisions. Turati was a moderate reformer who showed himself willing to work toward social change within the government. Ferri the revolutionary, however, is lampooned as a barefooted clown in short, striped pajama-like pants, with feathers sticking out below. This is a party rife with factions and, in the eyes of La Rana, deserving ridicule.

The so-called “interview” with Buffalo Bill mentioned previously in relation to the March 30–31 edition, further reinforces this message. A correspondent quizzes Cody about politics, and Bill’s zany replies become a commentary on domestic and international issues:

When asked about the current Italian government, Buffalo Bill replies “That of Italy is a spectacle without comparison.”

“What,” the interviewer presses Cody, “do you think about the direction things have taken?”

“My dear,” Buffalo Bill observes, “the direction is worth little without…any reins.”

As for the recent industrial strikes, Cody claims they were the result of “strange brains,” and that agitators would ultimately be left with “red skins”—a racist pun on the Indians intended to convey “blushing.”

Then, when asked again about the state of Italian politics, Cody offers this assessment aimed at the socialists: “Certain political parties play…the Indian.”

“Anyway,” Cody declares at the end of the interview, “it all comes down to knowing or not knowing how…to lead.”

Not surprisingly, the magazine then invites its readers to enjoy other stories about the Wild West and promises to offer up a “lavish, spiritual, ‘bill’iant’ banquet” in the April 1906 issue of La Rana…

Likewise, we invite you to find out more about La Rana‘s penchant for Buffalo Bill’s Wild West in the conclusion of “A leap, but not a stretch”

About the Authors

Mary Robinson is Housel Director of the Center’s McCracken Research Library. Robert Rydell is Michael P. Malone Professor of History at Montana State University in Bozeman, Montana.

Post 252