Giving Back to the Land – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Spring 2020

Giving Back to the Land: Volunteering for public lands heals the spirit and the landscape

By Corey Anco

What comes to mind when you think about a fond memory of spending time in nature? Fishing with a grandparent? Filling your first tag? Maybe it’s a particular hike with friends or family. Whatever the memory, there exists a fundamental need in us all to connect with nature and each other.

Numerous studies demonstrate that we need nature. Spending time outdoors reduces stress and anxiety, increases cognitive functions, reduces fatigue, increases productivity, and even shortens recovery time from injuries or illness. But as much as we need nature, it’s also true that nature needs us.

Federal public land management agencies nationwide rely on volunteers to help address a $19.4 billion deferred maintenance backlog. In 2019, approximately 156,000 volunteers contributed more than 620,000 hours of labor on National Public Lands Day, amounting to a collective contribution worth an estimated $16 million. Volunteers removed trash, improved trails, stabilized streams, increased fence permeability for wildlife, and performed dozens of other services to improve habitats for wildlife and for our enjoyment.

I live by this adage: if you cultivate an appreciation for nature at an early age, you will gain a lifetime of adventure and curiosity. Growing up just outside of Chicago, I was fortunate to have an undeveloped forest plot as my backyard. The crisp air filled my lungs as I crawled up and down ravines. Oak, maple, and ash leaves painted woodlands a sea of orange, crimson, and marigold each autumn—a picture burned into my memory as early as I can remember.

It wasn’t until my adulthood that I learned the forest of my youth was private property. Unbeknown to me, I was trespassing.

Recognizing how critical nature was to my upbringing, I built a career around it. I have moved around frequently over the past 10 years (12 cities, 5 states, 2 countries) pursuing professional and educational opportunities. Among them all was a common thread physically positioning me in nature or professionally tethering me to the outdoors. In 2017, I relocated to Wyoming and began a career with the Draper Natural History Museum. I was drawn to Wyoming’s wide-open spaces, wildlife, unrivaled vistas, quality of life, and unparalleled access to nature.

The region around Cody, Wyoming, is home to some of the most iconic landscapes in the world, offering recreational opportunities meeting nearly every outdoor enthusiast’s needs. But the number of public land users far exceeds those whose job it is to offset our impacts to these sites.

As public land users, we’re ethically responsible for taking care of these special places. When was the last time you had an opportunity to volunteer outdoors, but didn’t? Was there too little notice? Poor timing or an inconvenient location? Did you not want to go alone? Whatever your reasons, both the local outdoor volunteer base, as well as event organizers and leaders, are aging. And the largest user base of youth and young adult recreationists aren’t volunteering in significant numbers.

Much of the volunteer work on public lands is done through nonprofit groups and other organizations, said Cade Powell, Cody Field Manager for the Bureau of Land Management.

That work could range from Boy Scouts working on trail repairs to wildlife advocacy groups making fences easier for animals to navigate, he said.

“Volunteers enhance our programs and projects and many of the opportunities we have to improve our public lands, and they’re a great asset because they’re passionate about what they’re working on,” Powell said.

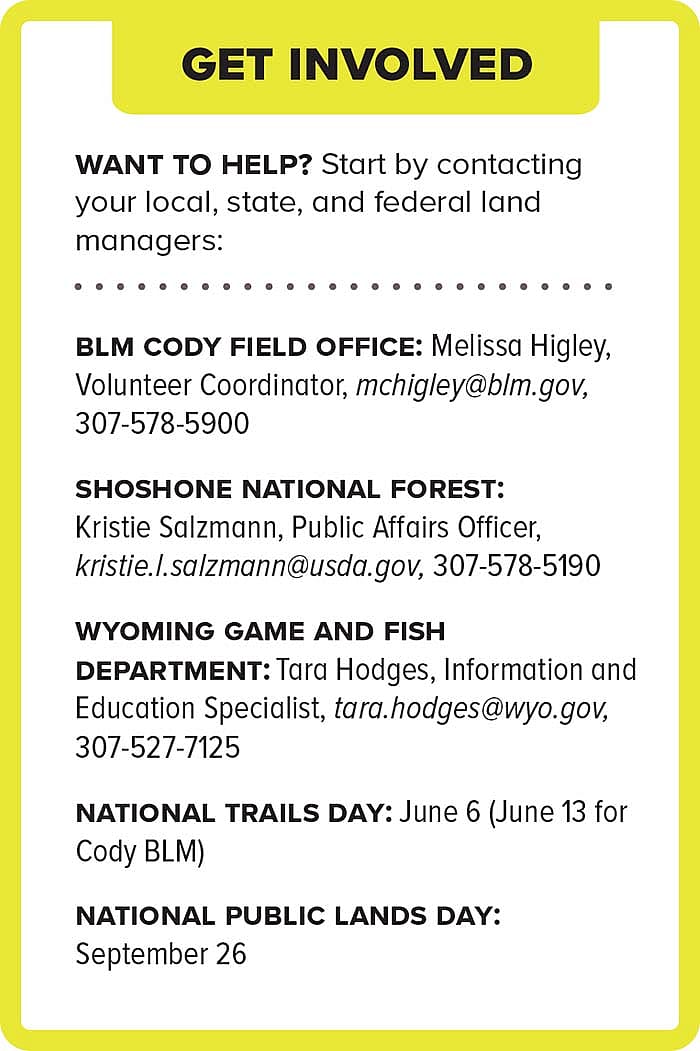

Agencies like the BLM and the U.S. Forest Service work to recruit volunteers throughout the year, but especially on days like National Public Lands Day in September and National Trails Day each June.

Volunteers often become involved more deeply with public lands and are generally more likely to show up for public meetings for land use planning, and to participate in other aspects of planning processes, Powell said.

“Individuals and groups also have a vast social media presence beyond what we can do, so it helps get the word out about whatever is going on and it’s a great way to make sure everyone’s voice is heard,” he said.

For Cody angler Dave Sweet, volunteering has been a long-term way to give back to the resource he has enjoyed for decades.

Sweet has worked for the past 15 years as part of the local Trout Unlimited chapter to rescue fish caught in irrigation canals and ditches in the fall and return them to larger reservoirs before those waters dry up or freeze over.

Sweet said he got involved at the urging of other Trout Unlimited members, including some who had been rescuing the stranded fish for decades.

“It just seemed like there was a need, because we were losing tens of thousands of trout to those irrigation ditches every year,” said Sweet, who also has worked to restore native Yellowstone cutthroat trout to backcountry streams in the remote Thorofare region near Cody and Yellowstone National Park.

Sweet and other volunteers work with the Wyoming Game and Fish Department to capture fish stranded in irrigation ditches, transferring them to trucks and releasing them in their streams and rivers of origin. He also helps install screens to make sure trout don’t get diverted into canals in the first place. The work can be difficult and time-consuming, but Sweet said he finds it rewarding.

“Fishing has given me so much enjoyment over the years that I feel the need to give back to that resource, and this is clearly a good way to do that,” he said.

Like most volunteers I have encountered, Sweet is retired. When asked why they volunteer, many people cite strong childhood memories: recollections of fishing with grandparents, camping with family, putting food on the table, awakening to an alpine sunrise. The common denominator reflects a positive relationship connecting us with nature and each other.

Researchers have found that the top reason people donate time is to “help the environment.” Critically, this benefit is mutual. Volunteering fulfills the desire to make a positive, tangible impact upon the environment, while being outdoors gets us away from screens and buildings, and into nature, where we receive numerous health benefits. When it comes to using time wisely, volunteering might be one of the best things we can do for ourselves and the environment.

Technology may link the world digitally, but we’re losing connections with our surroundings and each other. Socializing, while immersed in nature, nurtures the human experience. Giving back to the lands that provide us with so much helps connect us with something greater.

The time to start is now.

About the author

Corey Anco is assistant curator of the Draper Natural History Museum. He enjoys cooking, splitting wood, and hiking throughout the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Points West editor Ruffin Prevost contributed material for this article.

Originally published in Points West magazine in the Spring 2020 issue.

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.