A Modern Day “Hole-in-the-Wall” Gang’s Unexpected Journey – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Winter 2010

A Modern Day “Hole in the Wall” Gang’s Unexpected Journey

By Whitney Western Art Museum Volunteers

“While browsing through the Whitney Western Art Museum’s displays at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, it may be difficult to visualize all that happens behind the scenes,” [Then] Acting Curator Christine Brindza says, “Lending a hand to the staff are some very dedicated volunteers who help make the day-to-day operations appear seamless.”

Brindza tells how the curatorial staff assigned the self-proclaimed “Whitney Hole-in-the-Wall Gang” one daunting task: to reorganize the curatorial files of the art collection. The volunteers, not knowing what lay ahead, discovered numerous interesting facts about artwork and artists in the collection. Along the way, they built friendships and camaraderie, and gained new knowledge of western art—an adventure they decided to share with others.

Volunteers in “the gang” chose to highlight one artist or object that fascinated him or her and convey a small part of their experiences while working in the files. “Ocean explorer Jacques Cousteau once said, ‘If you know what is ahead, it will not be an adventure,’ volunteer Nancy Wulfing explains. And what an adventure these volunteers had meeting the most interesting “characters” along the way.

Charles M. Russell and the Saddle Ring: Did He or Didn’t He?

By Nancy Wulfing

In a file on Charles M. Russell (1864 – 1926), a black-and-white photograph of a ring designed in the shape of a saddle caught my eye. The file said it had been made by the famous cowboy artist for Nancy Cooper (1878 – 1940), his wife. Intrigued by the ring and its interesting story, I hoped to find out more about this unique object in the months that followed my discovery.

To begin with, I found that the saddle ring had sold in 2007 through Heritage Auctions Galleries in Dallas, Texas. Its website provided a color photograph of the saddle ring with information about its design and history. According to the site, the ring was cast from a gold nugget and is thought to be one of Russell’s first three-dimensional sculptures. If this is correct, the saddle ring was instrumental in the artist’s introduction to sculpture. In 1898, just two years after he married Nancy Cooper and supposedly created the saddle ring, Russell cast his first bronze at Roman Bronze Works in New York City.

Jack Russell, Charles Russell’s son, provided an affidavit—dated September 9, 1994—with the saddle ring, which states, “My father Charles M. Russell met my mother, Nancy Cooper, in Cascade, Montana… Charlie proposed to Nancy and to his surprize [sic] and relief she accepted. Charlie had little money, but much imagination, he took to her a ring duplicating his stock saddle…I was just a kid when Dad died. I’ll never forget when Dad gave me the saddle ring…” The affidavit further explains that Jack was given the ring in 1925 in his Great Falls, Montana, home, a year before Charles Russell died.

Never undertaking such a research project before, I read a number of books and articles on Charles and Nancy Russell, and it was a challenge to find more factual evidence about the saddle ring. Only one reference to a ring emerged, though it was not about the saddle ring in question. In his book, Charles M. Russell: The Life and Legend of America’s Cowboy Artist, 2003, John Taliaferro said that Russell purchased a ring in a hurry at a jewelry store in Great Falls before his wedding in 1896.

In my pursuit to find other references to the saddle ring, the C.M. Russell Museum in Great Falls referred me to Jim Combs, a collector of Russell ephemera. Combs recalled that he had seen the saddle ring many years earlier while visiting with a collector, Christopher Courtlander, of Garryowen, Montana. When he saw it, Combs thought that the saddle ring was too bulky in design to be worn by a woman. Further, Combs believed that the saddle ring was not created by Russell, but rather by one of his protégés, Joe De Yong. Combs remarked that Courtlander told him the saddle ring was made in Santa Barbara after De Yong moved to California. It is thought that the saddle ring was a part of De Yong’s estate, left to Dick Flood, a collector in Jackson, Wyoming, in the early 1960s. If this was the saddle ring in question, then how did it get into Jack Russell’s possession? Were other saddle rings made?

Who do you believe created this ring? From my point of view, the actual artist remains a mystery. With two totally different accounts about the creation of this very unusual ring, either western sculptor—Russell or De Yong—may have designed it. Clearly, more research needs to be done, and I hope to find more evidence in the future about its exact origin. Even so, this is an example of the exciting learning experiences I have had delving into the files of the Whitney Western Art Museum.

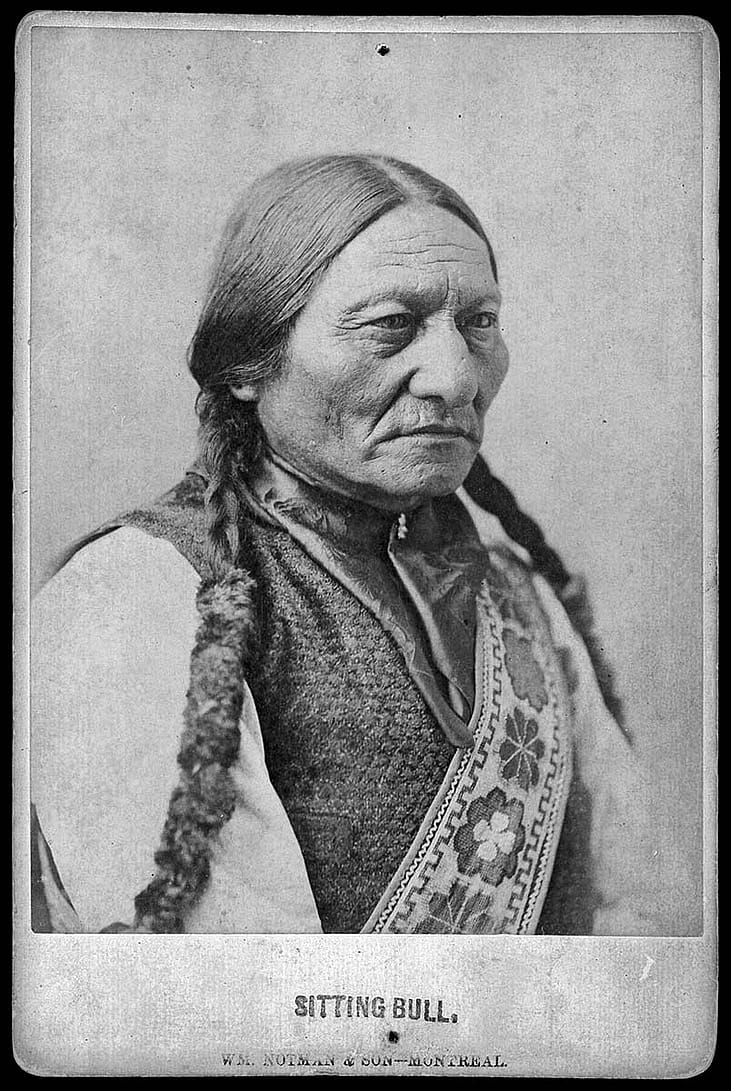

Sitting Bull—the Artist?

By Roger Murray

One day while working in the “S” files of the Whitney Western Art Museum, I found a folder labeled “Sitting Bull.” I knew of this famous Native American as the subject of various paintings, photographs, and historical events, so I thought this information might not belong in an “artist”file. As it turned out, however, Sitting Bull was also an artist.

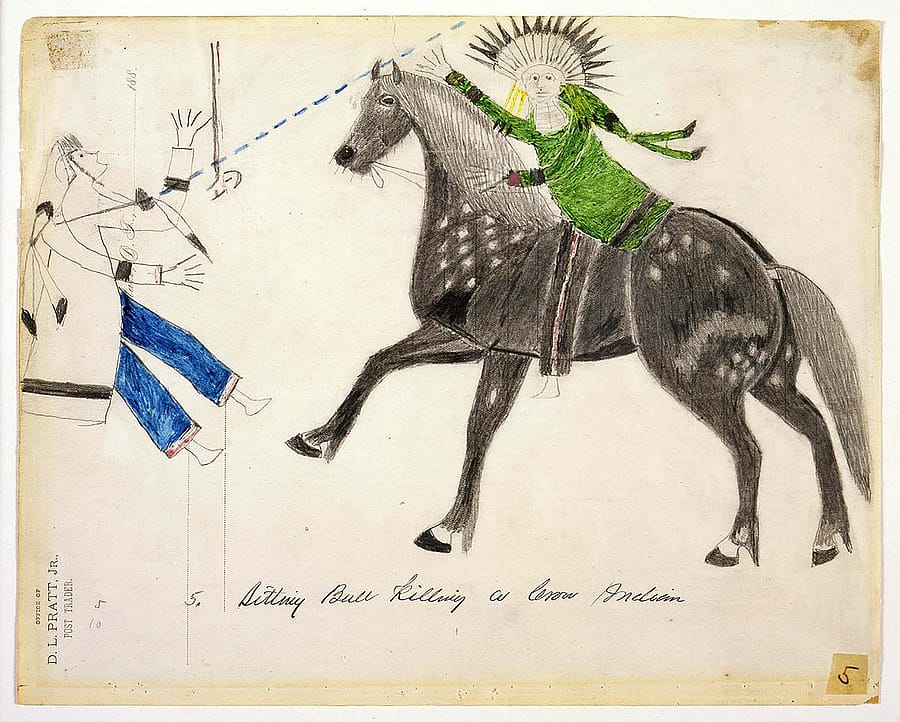

In the Whitney collection at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, there are fourteen drawings—or pictographs—attributed to Sitting Bull. They were created with pencil, ink, watercolor, and crayon on paper. To me, crayon did not seem to be a common media used by other artists in the collection, so I wanted to learn more.

Pictographs were created by Native Americans to remember important happenings in their lives. Traditionally, events were recorded on animal hides using materials found in nature. During the Reservation Period (1880 – 1960), ledger art replaced the hides, and Native artists used whatever materials were available, such as paper from ledger books and crayon. In this way, the stories were passed along to the generations that followed.

According to the records, when Sitting Bull was in “protective custody” at Fort Randall, Dakota Territory, in 1882, he is said to have drawn these images. Daniel L. Pratt, a post trader at the fort, kept the images, which he presented to G.H. Pettinger in 1925. The Center received the Pratt-Evans-Pettinger-Anderson Collection in 1970.

In Lakota tradition, pictorial records of an individual’s experiences are created by someone else, not the person himself. This further sparked my interest in these drawings: If Sitting Bull, rather than a relative, created the images of himself, they are extremely significant.

I learned that there is much more than meets the eye when it comes to art; it is more than just looking at a work of art on display. There are challenges in researching and determining the origin of drawings such as the Sitting Bull works. For example, the provenance—the ownership history of a work of art—helps determine authenticity. Records or original documents are used to discover the previous whereabouts of the pieces. Many may not realize the extensive record keeping and research involved for each work of art in the collection.

As I studied the background of artwork by Sitting Bull, I found that the deeper I explored, the more the questions outnumbered the answers. Determined, I will continue my research, however. In the meantime, taking on the volunteer job of filing has proven not dull at all: There are always new things to discover.

Artist Audrey Roll-preissler Takes on Tough Western Subjects with Humor

By Nancy Cook

The West continues to have a strong identity with the past and inspires artists like Audrey Roll-preissler, a contemporary artist whom I find to be fascinating. Quoting the artist, “…my specialty as a western artist is to spoof the West,” and she does it with flair.

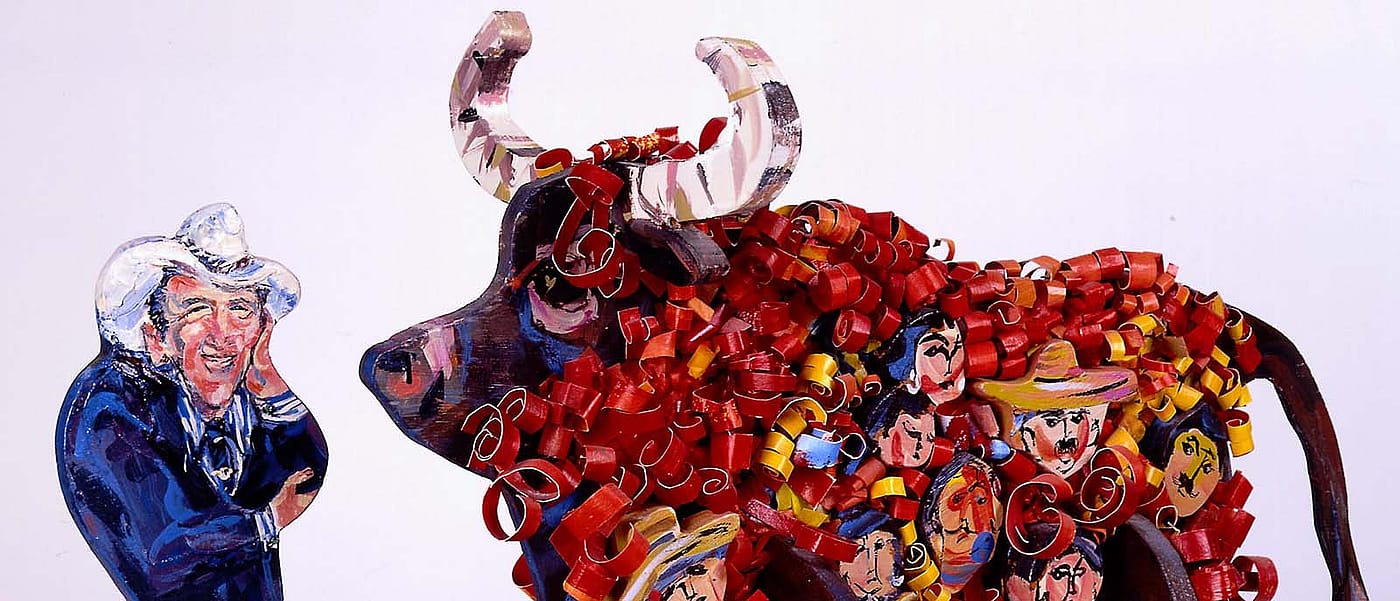

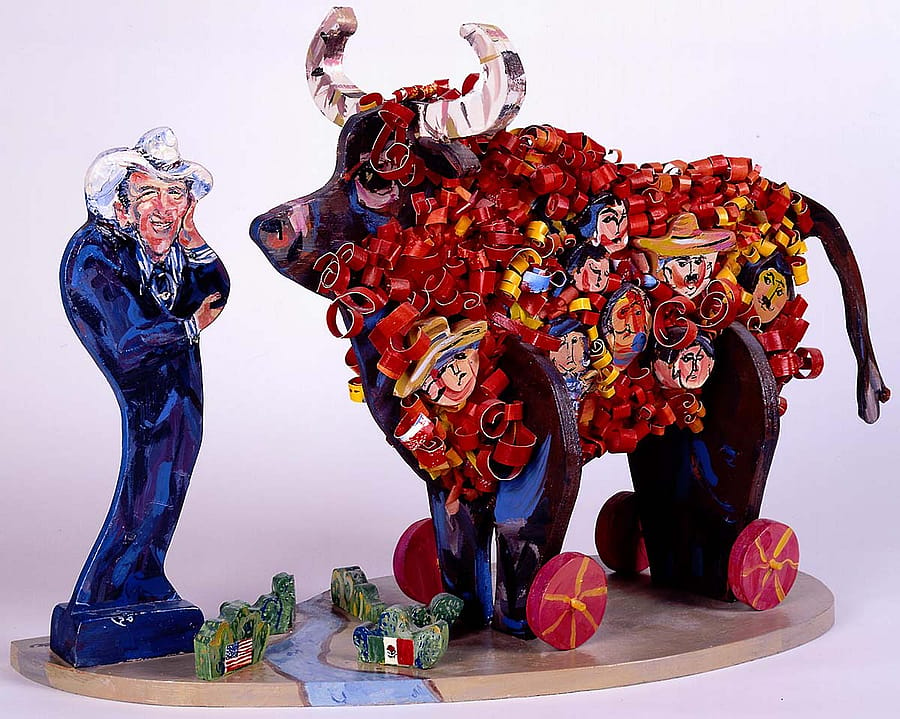

A remarkable work of art in the Whitney Museum collection shows how Roll-preissler converted a Greek legend into a work of art while representing a current political issue. Trojan Piñata (Portrait of Alan Simpson), a polychrome wood and paper sculpture, portrays a matador standing with a bull, decorated with paper curls and faces of Mexican immigrants. The matador is former U.S. Senator Alan K. Simpson, R-Wyo, who co-sponsored the Immigration Reform Bill adopted in 1986. Rollpreissler’s piece is a response to concerns about illegal immigrants, symbolized by the figures on the sculpture. This work shows how art can formulate commentary on difficult issues facing the West today.

While examining the files on Roll-preissler, I found her studies and plans for the work The Equal Opportunity License Plate particularly engaging. With humor, she created the Wyoming license plate depicting the famous cowboy on a bucking horse, but added a voluptuous cowgirl—after all, we are the “Equality State.”

In the late 1980s, while she was a professor at the University of Wyoming, Roll-preissler planned to create License Plate as a monumental outdoor work (standing 26 feet high) outside Cheyenne, Wyoming. Through the years, she continued to pursue placement and sponsorship for the work, but due to lack of funding, the final work did not materialize. What a sight that would have been!

In addition to reading files on this interesting woman artist, I had the privilege of visiting with her by phone. She openly shared events of her life’s journey and their influence on her creations. I hope to someday meet her in person.

These two pieces of Roll-preissler’s contemporary art have instilled in me an appreciation of how much art through the ages is influenced by issues of the day. Now, I will look at artistic works with a more discerning eye.

During our project, we discovered many facts, unanswered questions, and mysteries. After two years, we find that the files of the Whitney Museum continue to provide exciting art and history lessons.

Signing Off,

“The Whitney Hole-in-the-Wall Gang”

Nancy Wulfing, Roger Murray, and Nancy Cook

(We also would like to thank Rose Ginger, who started with us on our trip into the files.)

Post 321

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.