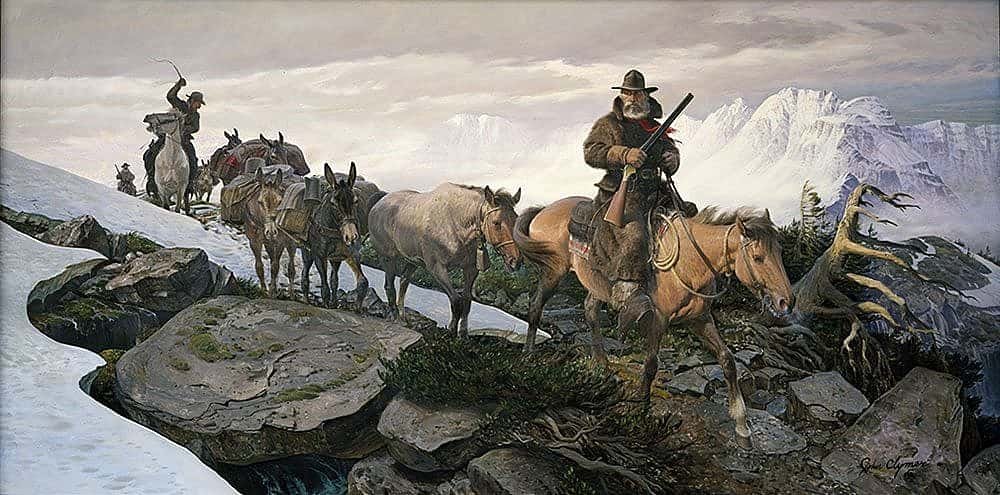

Echoes of the Painted West: John Clymer’s Gold Train

Gold in the Hills!

Colonel Mulberry Sellers in Mark Twain’s satirical novel The American Claimant prophetically decreed, “There’s gold in them thar hills, I tell you!” echoing the sentiments, dreams, and attitudes of Americans in the mid-19th century eager to head west to find their fortune digging for gold. The Gold Rush defined an American era, drawing thousands of Easterners to the frontier and beyond in pursuit of fortune. Renowned Western artist John Clymer captures this spirit by depicting a scene inspired by the Gold Rush, choosing Mosquito Pass in Colorado circa 1859 to vividly bring to life the experience of that transformative time.

Gold Train, one of three paintings by Clymer commissioned as a permanent gift to the Buffalo Bill Memorial Association by Winchester-Western Division, depicts a prospector bearing a Henry rifle while leading a train of pack mules carrying goods and supplies over Mosquito Pass, high in the Colorado Rockies. This one-frame narrative in oil-on-canvas remains on display today in the Buffalo Bill Museum at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming.

Formative Years and War

Born in 1907 in Ellensburg, Washington, John Clymer grew up with a love of the outdoors and a proclivity for mountain life. He developed an affinity for illustrating and painting as a teenager, creating window displays for the local rodeo in Ellensburg. At 16, Clymer sold some pen and ink drawings to the Colt Manufacturing Company as part of a national advertising campaign, thus beginning his storied career as an illustrator. Before long Clymer landed gigs with The Saturday Evening Post, Field & Stream, Women’s Day, and True Magazine to name a few. During the course of his career, he created over eighty illustrations for The Saturday Evening Post, depicting idyllic American scenes in small towns, often including patriotic themes. Not one to shirk his patriotic duty, John Clymer enlisted in the U.S. Marines during World War II where he used his artistic talents to create illustrations for Leatherneck Magazine and the Marine Corps Gazette. After the war, he resumed his illustrations for The Post.

Brandywine Influence

Clymer’s popularity grew steadily, built on years of persistence and a deep commitment to his craft. In the 1930s Clymer headed to Philadelphia where he spent time training alongside or under artists of the Brandywine School tradition which traces back to the great Howard Pyle. Pyle mentored another famous Western artist by the name of N.C. Wyeth of Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania. The Brandywine School, geographically located near the Brandywine River in southeast Pennsylvania, emphasized illustrating rich narratives, creating scenes from American landscapes, and emotive depiction of everyday American life. Clymer’s time in the Philadelphia region refined his illustration technique, with N.C. Wyeth as his primary inspiration. In speaking of his influences, Clymer once stated, “I patterned my life after N.C. Wyeth. I did not study with him. He didn’t have students. Your greatest teachers are your friends that help you.” In Philadelphia, Clymer concentrated on how to tell a story with realism and drama, which prepared him for his later work as an illustrator and then a highly successful Western painter.

Technique, Research, and Representation

The Brandywine School characteristics come through vividly in Gold Train. The composition descends diagonally and tells an American story—the 19th century Gold Rush—in one frame. This visually impactful piece of art measures 60” x 120” and provides a realistic glimpse into the Gold Rush era of the American frontier. The rough looking mounted rider clothed in animal hides confidently leads the pack train while carrying a Henry rifle—essential to the painting’s thematic link to Winchester’s legacy on the frontier. This sweeping composition highlighting human movement and drama stems from Clymer’s commitment to visual accuracy and theatrical clarity. At the insistence and encouragement of his wife, Clymer would visit museums and historical sites as part of his research before painting a scene, ensuring historical authenticity. The treacherous terrain, sharply descending landscape, and atmospheric haze accentuate the risk and peril of transporting goods and supplies in the Colorado Rockies, fully encapsulating the spirit of the American West on canvas.

A Lasting Vision

In the 1970s, Clymer moved to the mountains of Wyoming, transitioning exclusively to Western art. He painted every day with little interruption, focusing on wildlife and Western landscapes. Art collectors and museum curators began to stand in line to buy his work, making him one of the most financially successful Western artists of all time. Clymer lived a humble and quiet life, achieving his fame steadily through a true dedication to his craft. Gold Train showcases Clymer’s strengths as both visual narrator and fastidious researcher, inviting us to a historical experience that’s a monument to the preservation of the American West.

Written By

Jane Gilvary

Jane Gilvary is a Content Specialist in the Public Relations Department at the Center of the West. She writes and manages web content and serves as editor of the Center’s monthly e-newsletter, Western Wire. Outside of work, Jane enjoys exploring Wyoming’s backcountry and discovering its hidden treasures.