Buffalo Bill Band

Wild West Music of Buffalo Bill’s Cowboy Band

Essays and Liner Notes from: Wild West Music of Buffalo Bill’s Cowboy Band, performed by the Americus Brass Band, 1995

Introduction

By Paul Fees

One of the highest compliments paid to William F. Cody in the American and European press was the designation “Representative Man.” He represented the cross-section of qualities that identified the ideal American. He was self-made, well-spoken, ambitious but open-handed, sincere and democratic—he was, as Annie Oakley put it, “as comfortable with cowboys as with kings.” On top of it all, as a Medal of Honor winner, a famed guide, and a genuine frontiersman, he was authentic.

Cody was a man of his times, but he rose above his times sufficiently to help his audiences understand their world and reaffirm their faith in progress. The Civil War had been the defining event for him and his generation. In the West after the War, they found redemption and national unity. Band music, as played by Buffalo Bill’s Cowboy Band, was a perfect reflection of their temper—on the one hand sentimental; on the other, martial and progressive. In its blending of individual virtuosities it represented order, discipline, and the triumph of democratic unity: “E Pluribus Unum.” Above all, perhaps, it was highly entertaining.

As the following essays demonstrate, there were important messages conveyed by Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, “America’s National Entertainment.” An editor of the Chicago Tribune understood as he wrote about Buffalo Bill’s farewell: “He has been more than picturesque; he has been worthwhile.”

Paul Fees, Ph.D., Buffalo Bill Museum curator, 1981 – 2001.

Music for a Changing Nation: Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Goes International

By Richard B. Wilson

The music of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West unified the myriad sights and smells, narrative hoopla, and raucous sounds of a spectacle that aimed to satisfy showgoers by leaving their minds and imaginations overstimulated and exhausted. Sweeney’s Famous Cowboy Band did not just add another layer of stimulation; the musicians actually controlled the multiple energies of each performance as they moved the show’s segments along. The music provided a rope of continuity in a diversified extravaganza that seemed to hover throughout on the precipice of chaos. When the wild stimuli of the performance subsided, though, showgoers were left with a surplus of images and ideas. A century later, as we listen to digital recreations of the Wild West’s music, we have a much better sense of how profoundly and permanently Americans, as well as cowboys of the imagination around the world, have been affected by those images and ideas.

Exactly what changes in thought and imagination did Buffalo Bill’s Wild West effect? We can observe significant transformations in the image of Buffalo Bill himself and of the Wild West program between 1887 and 1906:

- The image of Buffalo Bill changed from the brave scout who defends and avenges western civilization’s highest values to an efficient entrepreneur who demonstrates modern American business practices to the European economic community. The romantic idealism embodied by the young Buffalo Bill blended with the savvy pragmatism of the seasoned survivor of history.

- Secondly, the image of Buffalo Bill changed from that of a national hero to an international ambassador who exploited his vigor and talent to demonstrate a model of cooperation that could bring about world peace. Cody’s historical role mirrored the shift in orientation of the United States from a country consumed with nation-building to a country cultivating a new role in twentieth century international politics.

- Finally, the image of the frontier as a place with fixed geographical coordinates was progressively translated into a psychological reality that could be effectively transported and reincarnated according to the fantasies of the viewer. The cowboy transcended his mundane role as a crude practical agent of historical change on the frontier to become chief actor in the cosmic psychodrama that has defined the myth of the West and, consequently, has profoundly influenced American ideology in the twentieth century. Because Cody and his company so effectively impressed their version of the West on the European imagination, our chief cultural export, “the westerner,” has undergone manifold transmutations in old and emergent cultures around the world during the past century.

When William Cody, Nate Salsbury, and John Burke took Buffalo Bill’s Wild West to Europe in 1887, they had already mastered the skill of psychologically distancing themselves from the facts of actual life on the Plains and in the Rockies in order to arrive at a more general and comprehensive definition of the American West. Burke’s often-used introduction to the Wild West program pointed to the heroic mission that the show’s organizers had defined for themselves: The story of our country, so far as it concerns life in the vast Rocky Mountain region and on the plains, has never been half told; and romance itself falls far short of the reality when it attempts to depict the career of the little vanguard of pioneers, trappers, and scouts, who, moving always in front, have paved the way—frequently with their own bodies—for the safe approach of the masses behind (“Salutatory”).

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West offered a “Truth” which was emphatically “Genuine” and which could be experienced, via fantasy, by each individual in the audience. In the space of two hours, one was transported within the imperiled safety of the Deadwood coach or planted firmly on horseback in the secure eye of an historic storm of global proportions. All the turbulence of international conflict and all the stresses of progressive empire-building were grandly resolved in the ultimately peaceful “interior” of the Wild West.

Inside the Wild West, showgoers battled the native of the West, but, at times, they became white Indians seeking safety from the advance of industrial civilization and modernity. Inside the Wild West, all races of the world found the means, twice daily, rain or shine, to master their threatening environments from the secure vantage point of the saddle. Buffalo Bill effectively exploited both the old technology of the railroad to move his entourage around the world and the new technology of electricity to stage his “Show of Shows” and “Race of Races” in the “Grandest of Illuminated Arenas” that was “Lighter than Day.”

In their nightly attempts to represent the quintessential western lifestyle, Cody and company not only redefined the status of the Westerner but went on to make the cowboy a type who represented America as a whole in both the American and European imaginations. That identification had been effected by 1893 just as Frederick Jackson Turner was declaring the frontier “closed,” and just as Americans were being forced into a serious reconsideration of their self-concept under the pressures of intensified immigration and a depressed economy. Stimulated by contact with an international community in Europe during the early foreign tours, Nate Salsbury expanded the central focus of the Wild West to include the “Congress of Rough Riders of the World.” After the Chicago World’s Fair, American and European audiences would be presented with an image of the American cowboy as the central figure in a global pageant that had horsemanship as its core premise.

The poster campaign that Cody’s publicists mounted in the eastern United States and in Europe reveals a clear sense of commitment to presenting the “genuine” realities of westering. During the first European tours, their proclaimed intention to transfer an accurate, unromantic depiction of western life “from prairie to palace,” from the United States to Europe, resulted in their dominant emphasis on the national significance of the pageant they were presenting. Within a very few years, as a result of contact with foreign audiences, the nationalistic meaning of the Wild West would be expanded to display an international significance.

The Wild West’s managers possessed an intuitive sense of changing audience interests, and they were continuously modifying the program to keep it responsive to the immediate moment. Cody, Salsbury, Burke, and, later, James Bailey of circus fame, could easily have frozen the history of the American West into a static tableau and appealed to nostalgic impulses in the late-nineteenth-century audience.

Instead, throughout the European tours of the 1890s, the Wild West producers insisted on depiction of contemporary events; linking those late-breaking news events to what had already transpired in the West resulted in a “universalization” of the frontier experience. In their translations of history, the American frontier experience became a metaphoric example of ageless conflict resolved in a model of cooperation; vastly different peoples discovered the simple value of camaraderie after intense battles that had nonetheless elicited displays of virtue on all sides. The Wild West show became a case example of whites and Indians rising above very recent conflicts to offer to the world an important lesson of history; by rehearsing very recent newsworthy battles, Cody became an explicator of current events who was teaching Europeans that the “grand lesson” of the American frontier was applicable to world conflict. Cody’s publicists bypassed no opportunity to spotlight Buffalo Bill as the single hero in whom the long-term processes of European-American history were converging at the turn of the century. By the middle of the 1890s, Cody’s publicists were straining the limits of rhetorical excess as they melded the American Cowboy with the American Indian in the person of Buffalo Bill to form the core of the ever-expanding Congress of Rough Riders of the World. The new sense of internationalism that the Wild West articulated combined chauvinistic militarism with a call for peaceful harmony among the nations of the world.

Visual depictions of William Cody continued a tradition of representing the true American as an amalgam of frontier roughness and urbane style. The leather-stockinged scout who appears in 1770 in Benjamin West’s painting, The Death of General Wolfe, comes full-circle in the figure of Buffalo Bill. For European audiences, Cody would slough some items of clothing that he would actually have worn in the West in favor of the costume details that would evoke his correspondence to “the look” expected by Europeans based on their popular literary fantasies. Cody reported that this gentrification during the European tours eventually resulted in Nebraskans and even Wyomingites expecting that he conform in dress to advertised images rather than to the fashion standards indigenous to the actual West.

During the first tour of England, a London journalist was already using the term “Buffalo Billism” to generically describe the powerful effect that Cody’s very visible image was having on the British imagination. While American audiences were responding to Buffalo Bill’s unique qualities that set him apart from a host of other popular heroes, Europeans were focusing on those aspects—particularly his adventurous and aggressive individualism—that marked him as distinctively American. As the figure of Buffalo Bill gradually synthesized frontier roughness and civilized sophistication, the cowboy’s skill and the Indian’s underlying nobility, he came to represent in the European imagination a composite of not only his diverse troupe but of the whole of American society.

It is during the 1890s that the Native American is redefined as “An American” and not primarily as an adversary to the advance of a superior civilization. The hostility and menacing nature of the Indian were never downplayed at any point during the European tours, but the publicity could control the power of the Indian’s threat by showing it as historical “fact” rather than as an immediate danger. However, if cowboys were stripped of their roughness or Indians of their savagery, then audiences would stop coming to see the dynamic Wild West and would start going to anthropological museums. And so, the image of the American Indian, during the run of the show in Europe, always hovered ambivalently between the stereotypical “wily” threat to Progress and the benign remnant of a vanishing way of life who ultimately indicts modern civilization.

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West was responsible for significant changes in the image of the westerner and the Indian both at home and throughout Europe. The look and now, thanks to this recording, sounds of the Wild West strike us all today as so familiar—in movies, in advertising, in fashion—because Cody and company were so successful at impressing their images of their West upon the twentieth century imagination.

Richard B. Wilson, Ph.D. teaches interdisciplinary classes in literature and film in the Humanities Division at Northwest College, Powell, Wyoming.

Exporting America to Europe: Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show and the Buffalo Bill Band

By Harriet Bloom-Wilson

When William F. Cody took his Wild West show to Europe four times between the years 1887 and 1905, he could not have asked for a more responsive audience, ready to accept his simplified and romanticized version of the settling of the West, and eager to have their own preconceived notions of the prairie americaine visually and tangibly confirmed. By all accounts this was an audience who looked to fictionalized versions of American frontier life not only as sources of adventure and romance but as examples of a free, open-ended way of life not possible within the clearly defined boundaries of European society.

The logistical enormity of the undertaking that involved moving a veritable city across the ocean was not lost on the overseas audiences either. In fact, the vast scope of the endeavor and the military precision with which it was carried out influenced the European perception of America as much as the content of the Wild West show.

Both the British and French press of the time lauded the heroic prowess and historical authenticity of the spectacle Cody brought to their capitals. Dynamic exhibitions of Indian and cowboy skills (foot racing, trick riding, lassoing, and sharpshooting), and the dramatic portraits of life in the West (the Pony Express, the Deadwood Stage, Custer’s Last Stand) were perceived as exact reproductions of daily scenes in frontier life, a tableau vivant of the western plains from a time gone by. What more stimulating backdrop on which to impose the childhood fantasies nourished by the consumption of American dime novels set in the Wild West?

However it was not just to learn American history and to relive childhood fantasies that Europeans went en masse to the Wild West. It was to assess firsthand the accomplishments, or failures, of that long lost relative who had set sail many years before for a new land filled with both promise and violence. And what better example of this new man could there be than William F. Cody himself, whose striking profile and long flowing mane seen on posters and in newspapers throughout the Continent came to represent a hero of almost mythological proportions?

The show had enormous power over its viewers. Many of its performers became models for impressionable youth abroad as well as at home. In fact, the show itself seemed to epitomize the suppleness and audacity often associated with youth. Frequent were the comments on the overwhelming physicality that punctuated each three-hour demonstration, reports which addressed the passion, vigor, and vitality that went into each performance and which revealed a fundamental admiration for the athletic skills that Americans were seen to have perfected. Here was Europe, the middle-aged parent, looking with a mixture of pride, awe, and trepidation at the accomplished individual his American child had become.

Like a number of other well-known Americans, Cody cast a far different shadow in America than he did in Europe where his audiences were less critical of the total image he was projecting. In the United States, he is often placed in the same category as showman P.T. Barnum, and, over the years, his detractors have often outnumbered his admirers. In fact, Cody was a consummate capitalist, but only one of many who were vying to capture the minds and dollars of Eastern Americans at the end of the nineteenth century. In Europe, there was little residual ambivalence to this American export. Archives today contain only remnants of the extensive coverage that he received in the European press, coverage that is dominated by a reverent and affectionate tone. These clippings corroborate reports published by Cody and his entourage which depict the Wild West’s reception abroad in superlative terms. The French, it seemed, loved it all, right down to the clothes worn by the performers; while in London, a critic labeled the performance a howling success.

While many scholars may argue that Bill Cody’s interpretation of the winning of the West is based almost entirely on illusion, they also concede that he profoundly altered the prevailing notion of the frontier, the cowboy, and the Indian. Wherever the show traveled, the Indian encampment was one of the more popular attractions on the grounds, and visitors were no doubt amazed at, and impressed by, the apparent harmony that seemed to exist between the red and white elements of the troupe, given their past and even current histories. Yet one more achievement of the new American, in general, and William Cody, in particular, was this ability to not only repel and ultimately conquer the “enemy,” as witnessed in two of the program’s events, but also to coexist with him in what appeared to be the greater American, or in this case Wild West, family.

Prior to Buffalo Bill, the European concept of the West was based on James Fenimore Cooper’s Natty Bumpo who roamed virgin eastern forests populated with Indians who lived in fixed settlements. The relationship between the individual and his environment was harmonious and the forest represented the possibility for renewal, rebirth, and revitalization. In Cody’s West, the wilderness, which had shifted to the Great Plains and deserts, existed to be conquered and civilized. Now the cowboy replaced the hunter as the hero of American culture, and brought with him an entirely new set of values appropriate to a closed frontier rather than a wilderness that required endless probing. It was only logical, therefore, that Europeans would welcome and respond immediately to the power of a new mythical figure. Ultimately, it is Buffalo Bill’s version of the new American type as depicted in his Wild West show which was bought outright, and which has endured into the twentieth century.

Harriet Bloom-Wilson is Assistant Professor of French and International Student Academic Program Director at Northwest College, Powell, Wyoming.

Buffalo Bill’s Famous Cowboy Band

By Michael L. Masterson

Buffalo Bill Cody’s life as a showman provides the time frame for the music found on this recording. Cornet player William Sweeney organized and directed Buffalo Bill’s Cowboy Band from the very beginning when Cody organized his first Wild West show at “The Old Glory Blowout” in North Platte, Nebraska, on the Fourth of July, 1882, to Buffalo Bill’s 1913 “Farewell Tour” with Pawnee Bill in the “Two Bills’ Show.” Providing music for Buffalo Bill after Sweeney came two of the twentieth century’s most famous band directors. Karl L. King, march composer and baritone horn player, led the band for the Sells-Floto Circus that hired Buffalo Bill for its Wild West specialty act in 1914 and 1915. In 1916, cornet player and later long-time director of the Ringling Bros. Barnum and Bailey Circus Band, Merle Evans, directed music for Buffalo Bill as band leader of the Miller Bros. 101 Ranch Show, Cody’s last employer before his death in 1917.

Though the Wild West show still attracts much attention from both historians and the general public, as observed in the previous essays, little regard has been given to the music that accompanied this influential exhibition. Excited by the show’s intense visual drama and the action-packed, mythic, arena storytelling, American and European audiences vicariously experienced specific historic incidents and other aspects of the western experience. To complete the show’s sensory experience, the Cowboy Band paced, animated, and expressed the necessary aural moods to enhance the performance and further thrill audiences, as does music at such contemporary cultural events as films, sports games, circuses, and more. This recording by the Americus Brass Band, perhaps America’s premier historical band, finally recreates for modern audiences the authentic, mostly nineteenth century sounds of this often-overlooked aspect of the Wild West performance.

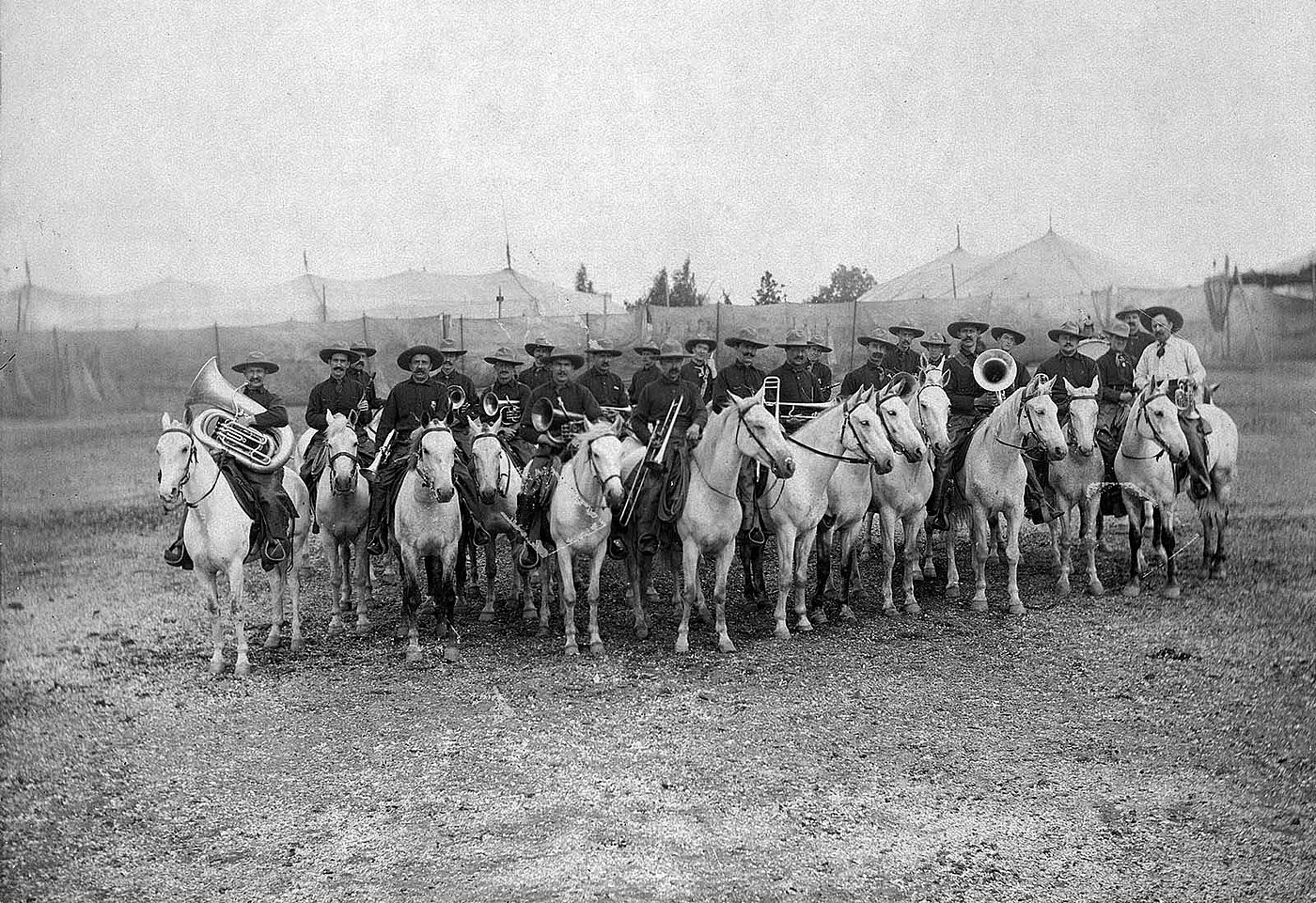

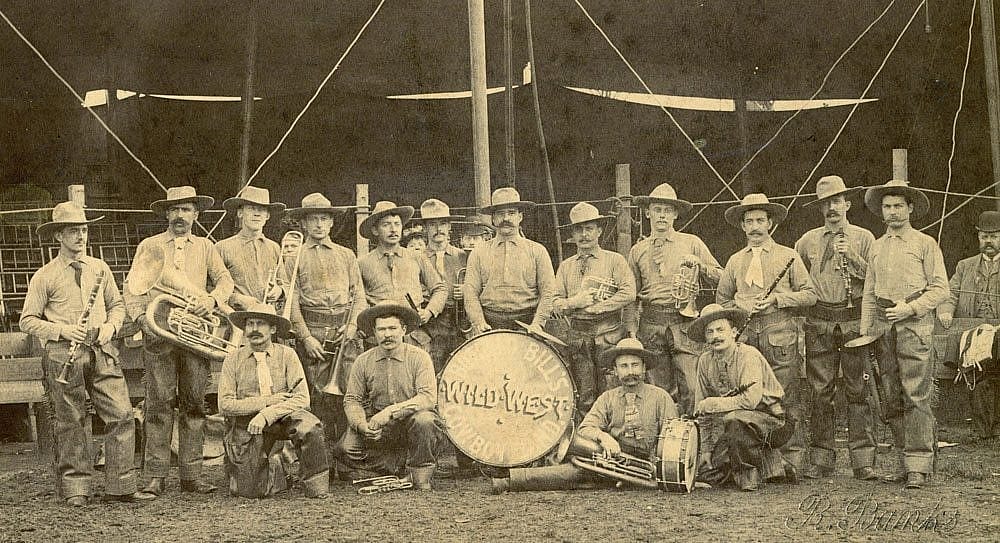

The Cowboy Band became famous by working hard. For many years a normal Wild West traveling day in America kept the Cowboy Band busy from morning until well after sundown. After traveling in a train all night to the next town on the schedule, the performers breakfasted early to prepare themselves for a late morning parade on the city streets. Featuring all the Wild West performers including cowboys, Indians, wild animals, Rough Riders from around the world, the Side Show band, other exotic performers, Buffalo Bill himself, and the famous Cowboy Band riding matched gray horses, the parade drummed up interest for the shows held later in the day.

The Cowboy Band was a moderately-sized band for the times. Photos of the 1887 Cowboy Band in London reveal a sixteen-piece band with a D-flat piccolo, an E-flat clarinet, three B-flat clarinets, three B-flat cornets including Sweeney, two trombones, a baritone, two E-flat alto horns, one tuba, a snare drummer, and a bass drummer. Listing a piccolo, four clarinets, three alto horns, five cornets, three trombones, a baritone, a B-flat bass tuba, an E-flat bass tuba, and two drums, the 1896 Wild West Route Book reveals twenty-one members in “Buffalo Bill’s Famous Cowboy Band,” the size band best represented in this recording.

A London newspaper in 1887 commented: “they (the Cowboy Band) upset all one’s previous ideas about the correct costume of musicians, but they play with spirit.” [1] Unusual for an era in which bands normally used military-style uniforms, the Cowboy Band wore attire based on the outfit of the American working cowboy. By wearing such a practical uniform based on clothes worn by actual western ranch workers, as observed in the accompanying photographs, the band reinforced hard-working western American images and values. Contrary to many publicity reports, however, most of the band members were not working cowboys from the West. For example, brothers John and Andrew Link, like many of the other band members, were hired in New York City before the Wild West ship left for London in 1887.

From their normal position in the corner of the Wild West arena between the reserved seats and grandstand seats across from the performers’ main entrance, the Cowboy Band regularly played a pre-show concert. Like most bands of this “Golden Age of Bands” era, the Cowboy Band played marches, patriotic tunes, “arrangements of popular songs of the day, all kinds of dance music from the waltz to the ragtime cakewalk, medleys of opera and operetta tunes, descriptive and novelty pieces, and transcriptions from the standard orchestral literature.” [2] Wild West programs often carried advertisements for music publishers stating that the Cowboy Band would play popular ragtime songs from their company’s catalog sometime during the band’s performance.

After the pre-show concert, the Wild West began in mid-afternoon and again in the evening with its official musical opening—the playing of the Star-Spangled Banner. This standard practice occurred nearly fifty years before the Banner became America’s official national anthem in 1931. Because of the thirty years of Wild West touring that helped spread this musical tradition, it could be argued that the general public’s acceptance of the Star Spangled Banner as our National Anthem demonstrates another example of Cody’s (and band director Sweeney’s) influence on American culture.

Following the Banner it was time for the Cowboy Band to “follow the tradition of circus bands everywhere and provide accompaniment for the various (Wild West) acts and bridges between acts” [3] such as The Grand Procession, Annie Oakley’s shooting act, the Pony Express, Capture of the Deadwood Mail Coach By the Indians, Buffalo Hunt, The Battle of the Big Horn, Custer’s Last Charge, Cowboy Fun, and more. [4] Though not a show or circus but an educational exhibition to the show’s managers and publicists, the Wild West functioned like a circus for the Cowboy Band with constant musical changes needed to aurally enhance the lively visual action in the arena. Their music paced, animated, set appropriate moods, heightened audience’s responses, and provided organized sounds to fill in the dead spots between acts. So similar were playing characteristics and repertoire of circuses and wild west shows that musicians, like director Merle Evans for example, often moved from one kind of venue to the other.

No recordings of the original Cowboy Band have been found, but the Brooklyn Times reported that the band provided an “obligato” for the performance. Buffalo Bill himself wrote about how “appropriate the music from Mr. Sweeney’s Cowboy Band” was to the show’s scenes of American history. [5] J. Jay Watson, writing for the London Evening News on July 25, 1887, called their playing “really beautiful music…a musical treat…and a musical combination worth listening to.” The London columnist for the New York World newspaper wrote on August 20, 1887, that the Cowboy Band “discoursed excellent music during the afternoon.” According to a story in the London Umpire on Sunday, April 1, 1888, the Cowboy Band presented to their director, William Sweeney, “one of America’s first cornet soloists,” a “handsomely engraved gold and silver-plated cornet, made and specially designed by the F. Besson & Co., London, England.” This evidence suggests that Sweeney and the Cowboy Band not only performed their functional tasks in the arena but also handled the aesthetic and virtuosic demands of their musician peers and the general public.

As heard on this recording, Cody brought to his audiences an American musical diversity representative of the times—styles like the ordered marches representing nineteenth-century notions of progress in American history, ragtime-influenced pieces embodying the cultural diversity of urban, industrial reality at the beginning of twentieth century, and light overtures and orchestral transcriptions demonstrating European culture’s continued influence on America. Complementing the show so well, Buffalo Bill’s Famous Cowboy Band reinforced the values of the Wild West show. According to band historians Margaret and Robert Hazen, nineteenth-century American bands in general “appealed to the emotions of a people struggling to create an orderly society on a vast and forbidding continent”—a notion that also applies to the Wild West show itself. [6] By virtuosically playing on their own particular “tools of the trade” a repertoire consisting of orderly music appealing to a wide audience, the Cowboy Band musically exemplified the values of the Americans that filled the Wild West grandstands. Though often performing in the background, the Cowboy Band’s aural contribution to Buffalo Bill’s Wild West enhanced its ability to achieve popularity and cultural influence.

The original Cowboy Band playbook of marches, popular and other songs, overtures, and arrangements has not been discovered, but old programs, advertisements, writings, and musical scores provide evidence regarding the music played by the band. This recording provides a sampling of this music. With their own enthusiastic, exciting, nuanced, and virtuosic playing, the Americus Brass Band brings to life the energy, effort, cultural implications, and quality of Buffalo Bill’s original Famous Cowboy Band. [7]

Michael L. Masterson, Ph.D. is retired from his position of Professor of Music in the Visual and Performing Arts Division at Northwest College, Powell, Wyoming.

Notes

- Don Russell, The Wild West: A History of the Wild West Shows (Fort Worth, TX: Amon Carter Museum of Art, 1970), 20.

- James R. Smart, Record jacket notes on The Sousa and Pryor Bands: Original Recordings, 1901 – 1926 (New York: New World Records, NW 282, 1976).

- Sarah Blackstone, Buckskins, Bullets, and Business: A History of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1986), 55.

- Wild West show programs available in the Western History Section of the Denver Public Library Denver, CO; the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, WY; or at the Circus World Museum, Baraboo, WI.

- W.F. Cody, Story of the Wild West and Campfire Chats (Chicago: Charles C. Thompson, Inc., 1902), 752.

- Margaret Hindle Hazen and Robert M. Hazen, The Music Men: An Illustrated History of Brass Bands in America, 1800 – 1920 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1987), 11.

- Portions of this essay were originally published in my article, “Buffalo Bill’s Band,” in the March 1995 issue of The Instrumentalist magazine. Copyright 1995 by The Instrumentalist Company. Reprinted by permission of The Instrumentalist, March 1995.

Liner Notes

By Michael L. Masterson

Cowboy Band music and the Wild West show were a perfect fit. According to Wild West programs, the Wild West show acts visually celebrated the frontier taming process that “smoothed the way for millions to follow.” In their musical support of the show, the Cowboy Band, with their ordered marches, patriotic songs, popular selections, classic overtures, and other exciting band arrangements, aurally smoothed the often rough and rugged edges of folk, ragtime, Indian, and other music to make them culturally acceptable and even thrilling to the American and European audiences (that also numbered in the millions). This recording features versatile selections that are energetic, dramatic, virtuosic, relentlessly cheerful, occasionally pompous, and sometimes culturally inconsiderate. As played by the Americus Brass Band, however, the music is always engaging, revealing in its performance many attitudes of the Wild West era. Wild West artifacts, posters, films, histories, programs, and other memorabilia have been studied and observed by interested people for decades, but with this recording of Cowboy Band music, almost a hundred years after Buffalo Bill’s Wild West folded its tents, modern civilization nearing the twenty-first century can better understand the total sensory impact of that famous nineteenth century cultural spectacle—Buffalo Bill’s Wild West.

Selections and Notes

- Star Spangled Banner, taken from Recollections of the War: A Grand Medley of Old War Songs, 1885. Edward Beyer. (1830 – ?). Prefaced by a musical “commence firing,” this song, now the American national anthem, was the official, ritual opening of the Wild West.

- See, The Conquering Hero Comes. G.F. Handel (1685 – 1759), from the Squire’s Cornet Folio, 1876, arranged by Froelich. This piece was taken from Handel’s oratorios, Judas Maccabeus and Joshua. As reported by newspapers of the day, it was played during the opening presentation of performers as Buffalo Bill himself galloped into the arena past the Indians, Rough Riders, cavalry, cowboys and other performers, to receive cheers, accolades, and often a standing ovation from the audience. This music bestows on Cody a heroic stature of biblical proportions.

- Buffalo Bill himself introducing a portion of the Wild West show taken from an old Berliner recording: “Permit me to introduce to you a Congress of Rough Riders of the World.”

- Gilmore’s Triumphal March, 1886. Thomas Preston Brooke (1854 – 1932). The Cowboy Band often played for more than just the show itself. Over the years, the Wild West performing schedule allowed for other musical pursuits, especially when the show established a residence in a long-term location, in particular at the London Exposition in 1887. From concert program information collected by 1887 Cowboy Band horn player Andrew Link, the Cowboy Band played regularly in London near the American Exhibition. A newspaper ad disclosed: “An Afternoon and Evening Concert, 3:30 ’till 5:30 and 6:30 ’till 9:30 will be given each Sunday by the Lower Grounds and Orchestral Band, and by the Cowboy Band, at the Aston Lower Grounds.” Both Color Guard March by Thomas H. Rollinson and Selections from Offenbach’s Operas were originally played on November 6, 1887. November 20 found the Cowboy Band performing Gilmore’s Triumphal March by Thomas P. Brooke along with another opera medley. Other concerts from the series included the entire Recollections of the War: Grand Medley of Old War Songs along with Sousa marches and other pieces. The playing on programs in Europe of standards from the “classic” repertoire along with new American band music demonstrates the Cowboy Band’s versatility, virtuosity, and ability to provide familiar music to their old world audiences and also educate them about new world sounds.

- Color Guard March, 1885. Thomas H. Rollinson (1844 – 1928).

- Offenbachiana: Selections from Offenbach’s Operas. Jacques Offenbach (1819 – 1880), E. Boettger, arranger, 1884. Bluebeard, La Perichole, La Belle Helene, Genevieve de Brabant, La Jolie Parfumeuse, La Grande Duchesse, Orpheus.

- Buffalo Bill’s Equestrian March, 1903. William Paris Chambers (1854 – 1913).

- Marche Russe, 1890s. Louis Ganne (1862 – 1923), arr. Louis-Philippe (L.P.) Laurendeau (1861 – 1916), 1901. The Cowboy Band often tried to capture the ethnic spirit of the Wild West performers with their music. This march let the audiences know in sound that the Russian Rough Rider performers were entering the arena.

- Sweeney’s Cavalcade, 1903. William Paris Chambers. Chambers, a famous turn-of-the-century cornet virtuoso and composer, wrote these two pieces specifically for Cowboy Band director William Sweeney to use in the Wild West show—likely for riding acts given the descriptive titles.

- Albion: Grand Fantasia on Scotch, Irish, and English Airs, 1908. Ch. Baetens, arr. M. E. Meyrelles. Blue Bells of Scotland, Garry Owen, Charlie Is My Darling, Annie Laurie, British Grenadiers, Last Rose of Summer, Minstrel Boy, Home Sweet Home, Tulloghorum, and God Save the Queen. Listed in the 1913 program as one of twenty-nine possible pieces to play in the opening concert preceeding the Two-Bills’ Show, this medley overture, like the previous one of Offenbach’s music, demonstrates Buffalo Bill’s and the Wild West’s close cultural ties to Europe. They traveled there for four extended stays in the Wild West’s thirty years. Albion is the name for the British Isles used by the Greeks and Romans. This collection of famous folk, popular, and patriotic songs from the islands develops themes in symphonic ways, again demonstrating the quality playing of both the Americus Brass Band and the original Cowboy Band.

- The Two Bills’ March and Two Step, 1910. William Sweeney (1856 – 1917). Sweeney likely did much arranging and composing during his almost thirty years as Cowboy Band director, but only two published marches of his remain in Wild West archives. The Two Bills’ March and Two-Step was dedicated to Buffalo Bill and Pawnee Bill who toured together for a few years at the time of the 1910 copyright, and Buffalo Bill’s Farewell March and Two Step was published in 1911 during Cody’s final tour. According to former circus band director William G. Pruyn both of these contrapuntal, ragtime-influenced pieces often accompanied the Grand Entry. [2]

- Buffalo Bill’s Farewell March and Two Step, 1911. William Sweeney.

- Wyoming Days, 1914. Karl L. King (1891 – 1971). King’s Wild West music included such marches as this one, written for the cowboy riding act. The Wild West was a noisy show represented by the yelling and gun shots heard in this music.

- On the Warpath, 1915. Karl L. King. This piece reveals dominant cultural attitudes about Native Americans common to the times. A so-called Indian characteristic number, it uses stereotypical Indian sounds still heard in old western movies and at athletic events. This specialty march was used during the 1914 Sells-Floto Grand Entry of performers, and again in the Wild West portion of the show, “a thrilling spectacle of past and present.” Publicists reported that this new number “was very well received.” [3]

- Grass Dance. The Plenty Coups Singers from Pryor, Montana: Gordon Plain Bull, Samuel Plain Feather, and Phyllis Plain Bull. The Wild West arena was often filled with authentic Native American music as well as band music. Music like this Grass Dance occurred during the Indian acts as they demonstrated some of their lifeways for European and American audiences. Show Indians from the Wild West show actually passed songs like this from tribe to tribe as they returned to their homes after the show season. In this Crow tribe version of the dance, no words are used, but it follows a regular grass dance song pattern of repeated phrases in fours. This style of music with its secure drumming and textured singing continues at contemporary powwows. [4]

- The Passing of the Red Man, 1916. Karl L. King. This brief programmatic concertpiece that musically considers the fate of American Indians during the nineteenth century, was dedicated “To my esteemed friend, Col. Wm. F. Cody, ‘Buffalo Bill’.” Cody enjoyed this mini-overture in particular. Merle Evans reported that Buffalo Bill “used to come to the bandstand during the (pre-show) concert with the Wild West show and ask me to play it for him.” [5] Passing of the Red Man musically depicts the interplay between the Red Man and White Man on the frontier during the nineteenth century. After a provocative introduction evoking fateful possibilities of things to come, the stereotypical Indian characteristic music familiar to the times begins, but is taken over by White Man music in the second section. A musical battle between the two themes ensues, but as in the reality of the times, the White Man music wins. The music ends like it began however, quietly, encouraging thoughtfulness regarding the possible consequences of the nineteenth century battle for the frontier West.

- Gallant Zouaves, 1916. Karl L. King. Composed for the amateur, military precision zouave drill teams prevalent at the turn of the century, this march includes an excerpt from the famous military song, The Girl I Left Behind Me, in the woodwind parts at the trio.

- Tenting Tonight On the Old Campground. Walter Kittredge, arr. W.S. Ripley, 1910. Affected deeply by the Civil War like so many of his generation, this moving tribute to the soldiers of that era is reported by many sources to be Buffalo Bill’s favorite song. Cody died early in 1917. His long-time friend and band leader, William Sweeney, died later that year. This florid, concert-style arrangement, created fifty years after the war, with its bugle calls, fast-moving woodwind parts, and excerpts from the Star Spangled Banner, evokes the post-Civil War “winning of the West,” the decorative notions of Victorian aesthetics, and the grandiose, mythic Wild West show. It becomes a tribute to Buffalo Bill’s life as an American hero and fitting end to this recreation of the music of Buffalo Bill’s Cowboy Band.

Notes

- In the Strobel Collection at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming.

- Phone call with Mr. Pruyn, August 17, 1995.

- Gordon M. Carver, “Sells-Floto Circus 1914 – 15,” in Bandwagon, Fred D. Pfenning, Jr., ed. (Columbus, Ohio: The Journal of the Circus Historical Society, Nov.-Dec., 1975), 22-29.

- George P. Horse Capture, Pow Wow (Cody, Wyoming: Buffalo Bill Center of the West, 1989), 8 – 10.

- Don Russell, The Lives and Legends of Buffalo Bill (Norman, Oklahoma: The University of Oklahoma Press, 1960), 459.

This recording occurred because of the assistance of many people and institutions. Thanks especially to the Foundations of Northwest College and the Buffalo Bill [Center of the West] who provided the funding for this project. Thanks also to The Instrumentalist magazine, Catherine Sell, editor and James T. Rohner, publisher; the Western History Section of the Denver Public Library; the Buffalo Bill Memorial Museum, Golden, Colorado; the Chatfield Brass Band Lending Library, Chatfield, Minnesota; Thomas Morrison at Buffalo Bill’s Ranch, North Platte, Nebraska; Fred Dahlinger and Menzie Behrnd-Klodt at the Circus World Museum, Baraboo, Wisconsin; Albert Rice at The Kenneth G. Fiske Museum of Musical Instruments, Claremont, California; Christina Stopka, Frances Clymer, Jan Woods, Christine Reinhard, Lillian Turner, and Peter Hassrick at the Buffalo Bill [Center of the West], Cody, Wyoming; and Robert Sauerwein, Neil Hansen, Jan Kliewer, Pam Johnson, Deanna Shirek, Sheila Jeannotte, President John Hanna, and Printing Services at Northwest College, Powell, Wyoming.

Thanks also to Richard Birkemeier, Bryan Shaw, Kurt Curtis, Jeffrey Reynolds, John McEuen, Richard Wilson, Harriet Bloom-Wilson, Paul Bierley, William G. Pruyn, Janet Strobel, Gordon Plain Bull, Samuel Plain Feather, and Phyllis Plain Bull. Special thanks go to Brett DeBoer for his graphic artistry; Paul Fees, former curator of the Buffalo Bill Museum at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, who supported this project in so many ways; Minnie Shadle Collins, an 1896 Wild West show audience member; and Pamela Citino Masterson.

Michael L. Masterson, Wild West Music of Buffalo Bill’s Cowboy Band Recording Project Director