Frank Hopkins

Weaving a Cinematic Web: Hidalgo and the Search for Frank Hopkins

By Juti A. Winchester, Ph.D., Former Curator, Buffalo Bill Museum

People frequently ask me what a curator’s job entails. At the Buffalo Bill Museum, I oversee and develop the Cody-related collections, I perform research for exhibits and publication, and I educate the public in various ways about Buffalo Bill. I spend some of my time thinking about ways to make history interesting to non-historians. Another aspect of any curator’s job is answering inquiries by researchers. This is the brief story of a seemingly small research query that assumed epic—or more appropriately Hollywood—proportions.

Since the earliest days of the movies, people have been making films about Buffalo Bill. William F. Cody himself appeared in some of the first silent films recorded by Edison, and later played himself in Life of Buffalo Bill (Pawnee Bill Film Company, 1912) and The Indian Wars (Essanay, 1913). Over the years, at least thirty-nine movies have featured Cody as a character or as the main subject. One more—Hidalgo—hit the big screen in 2004.

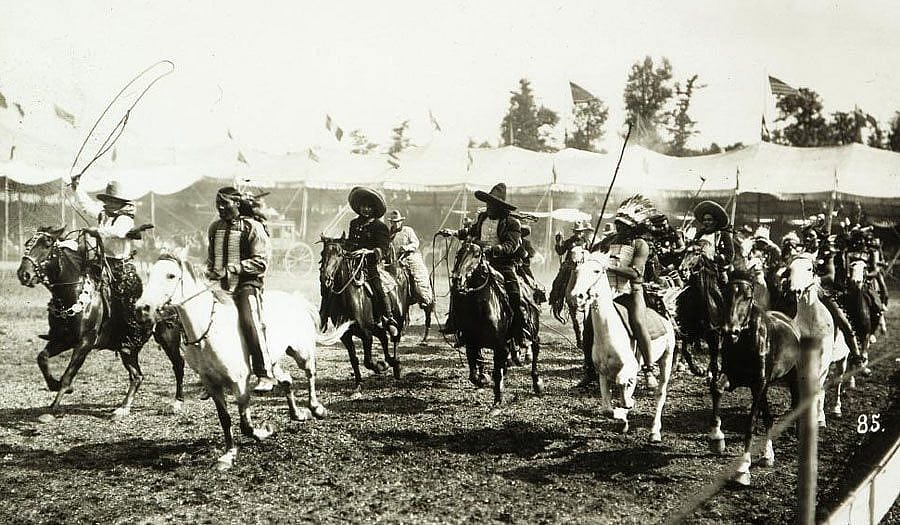

A Touchstone Pictures film, Hidalgo stars Viggo Mortensen as Buffalo Bill’s Wild West cast member and cowboy Frank T. Hopkins. In the movie, Nate Salsbury sponsors Hopkins and his mustang Hidalgo (played by “T.J.”) in a three thousand mile race across Saudi Arabia in the early 1890s, pitting the pair against Arabian horses, hostile and wily foreigners, and an impossible climate. The movie trailer shows a visually stunning epic starring a personable little paint horse and his disaffected, sculptured-jawed human companion who dash through a variety of locations (including a re-creation of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West) and through a multitude of dangers, finally winning the day with American pluck and determination. The advertising proudly proclaims: “Based on a true story.” In the case of Hidalgo, though, truth is an elusive commodity.

For several months beginning in March 2002, Buffalo Bill Museum Curatorial Assistant Lynn Johnson Houze and McCracken Reference Librarian Mary Robinson answered inquiries from members of the Hidalgo film research crew. They wanted to put together the most accurate portrayal of Buffalo Bill possible, they claimed. What kind of cigar did he smoke? Could the museum provide a schematic of the Wild West show’s layout? How were the stands constructed? The researchers also asked some very interesting questions, such as, “Was the Wild West segregated according to race?” Lynn and Mary provided them with information, and we looked forward to seeing the finished movie with high hopes that somebody would finally get Buffalo Bill right.

Late in 2002, we began to receive inquiries regarding Frank Hopkins, the film’s main character, who was supposed to have worked for Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. Our files and databases revealed nothing about this man who claimed to have had a long and publicly lauded career with Cody, and we were somewhat puzzled. However, information comes to us all the time, so we were confident that if Hopkins were a legitimate Wild West cast member, we would eventually turn over the right rock and find him. Lynn and I could scarcely believe the nature of the information that finally surfaced, thanks to some unofficial long-distance volunteers.

While conducting his own research on Frank Hopkins in early 2003, author and independent journalist CuChullaine O’Reilly contacted the Buffalo Bill Museum. Members of The Long Riders’ Guild, O’Reilly and his wife Basha maintain a website that records feats of equestrian endurance, and like the others who previously inquired, they were looking for independent verification of several of Hopkins’s claims. When we replied that we had nothing in the William F. Cody Collection that mentioned anyone named Hopkins, the O’Reillys’s hunt began in earnest, and Wyoming proved to be a fruitful field. In a feat of research endurance, they uncovered hundreds of pages of material written by Hopkins himself, including a copy of a manuscript hidden in the Don Russell Collection at the McCracken Research Library, and copies of other works, plus letters and photographs, in the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming. The O’Reillys generously shared everything they found with the Buffalo Bill Museum.

Always interested in what Cody’s contemporaries had to say about him, we studied the articles and found that nothing Frank Hopkins had written about Buffalo Bill, the Wild West, or anything connected with them resembled fact. Hopkins claimed to be a headline act for the Wild West’s first and second European tours, but when we examined historical records such as ships’ manifests, program books, and the extensive newspaper clipping scrapbooks, we discovered no evidence that anyone named Frank T. Hopkins had anything to do with Buffalo Bill or his exhibition. Months of diligent searching by Lynn, two hardworking interns, and myself revealed no independently verifiable record of Hopkins, who was supposed to have worked for Cody for thirty-one years and even to have been present at his death.

As members of the press learned of the O’Reillys’s search, journalists representing magazines, American and foreign newspapers, television stations, and National Public Radio called the Buffalo Bill Museum offices with questions about Hopkins. In April 2003, a History Channel crew came to the Buffalo Bill [Center of the West] to film a documentary, “The Search For Frank Hopkins,” which first aired March 4, 2004. Every questioner has asked, “is Hidalgo really a true story, as the filmmakers claim?” Sadly, we have had to inform them that it is not, at least from the perspective of Hopkins’s non-existent connection with Buffalo Bill and the Wild West. It’s a great story, but it never happened.

The Hopkins search is far from over. With the release of Hidalgo and the History Channel documentary, Buffalo Bill Museum staff members anticipate an upsurge of interest in Buffalo Bill, the Wild West, and unfortunately, the movie’s lead character. Sadly, my job as curator will include disappointing people, at least when they ask for more information about their new hero Frank T. Hopkins.

Since the cowboy first aimed his gun at the cinema audience in The Great Train Robbery (Lubin, 1903), movies, and especially westerns, have entertained and fascinated us with their stories, their landscapes, and their characters. Modern audiences will be interested anew in mustangs, cowboys, and Buffalo Bill, thanks to the power of Hidalgo‘s visual imagery and the acknowledged influence of moving pictures on the public. But, like they’ve been telling us for about a hundred years, you can’t believe everything you see in the movies.