Golden Eagle Journal, July 22, 2011

22 July: At least one of our nests has a young eagle yet to fledge! This bird is at least 62 days old and reluctant to leave the safety of the nest. This nest is more than 65 feet from the nearest safe ground, so this youngster may be wise to hang on for a while.

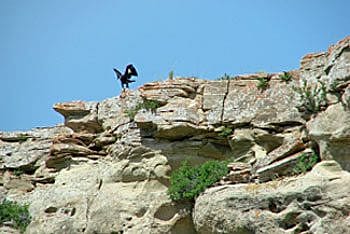

Four eagles fledged last week from three different nests. We caught up with one of the fledglings perched on a large rock outcrop about 100 meters away from its nest. We watched it for about 30 minutes before it took flight! It flew with strong wingbeats for about 250 meters, then began gliding and landed a bit awkwardly on a sagebrush-covered hillside across the canyon. The bright, white band on the tail and stark, white wing patches were clearly visible to us. Summer is in full swing now, with temperatures in the low-mid 90s most days.

Golden Eagle Posse member Anne Hay filed this report and photograph shortly after the eagle she had been monitoring left the nest:

“I was unable to visit the nest until Wednesday morning, and sure enough, the chick had abandoned the nest. The only bird I saw in the nest was a swallow, picking through the nesting material. I began searching, and 23 minutes later I spotted the fledgling standing near the ground on a small rock, west of the nesting area. About an hour after I arrived, the fledgling began calling out loudly. In the past, this usually meant an adult was visible, and sure enough, a parent arrived, dropping a small rabbit for the fledgling to dine on. The fledgling immediately ran to the prey and began mantling it, combined with peeping. The parent only stayed for 3-minutes. The fledgling fed for around 32 minutes, then walked a short distance west, and flopped down flat on the ground with its wings outstretched on either side. YIKES! Am I glad this wasn’t my first sighting of the fledgling! It looked like a dead eaglet! It only laid this way for 6-minutes, then it flapped/jumped onto a low rock in a shady area. It spent some time jumping between rocks in the sun, and rocks in the shade, preening, or looking around. At one point a female grackle began to harass the fledgling. This bird flew around the fledgling, from near-by rock to near-by rock, in two separate sessions, continually calling out. The grackle stayed for 19 minutes the first time, and 18-minutes the second time. Sometimes the fledgling watched it, sometimes it ignored it. Once the grackle flew at the fledgling, and pecked its tail.

Mid-afternoon an adult glides past, traveling north, over the rock formation and out of sight. The fledgling spies it, and begins calling. About five minutes later the fledgling begins moving west, first slowly, then faster, then it begins climbing the hill, hopping from rock to rock with some wing flaps until it is at the top of the ridge! From here the fledgling did a lot of looking around, preening, a little wing exercising, as well as a few very short flights along the ridge line. Twice the eaglet walked over the ridge top to the north, and out of my sight, then a short time after again reappeared on the top of the ridge line. I kept waiting for the flight off of the ridge, hoping it wouldn’t be a landing on the highway, but by 4:30, the fledgling still hadn’t taken the big leap. What a fascinating day!”

I’ve just begun to summarize our data from this year and compare with the previous two years. I’ll save details for our peer-reviewed papers, but this year has been quite a departure from 2009 and 2010 in several respects. The number of active nests this year was only about half of the number we’ve seen in each of the last two years, and far fewer of the active nests contained more than one chick. Our nighttime surveys indicate that both jackrabbit and cottontail populations have dropped markedly this year. We will be analyzing all of these findings for the next several weeks, but this study is becoming more and more interesting and stimulating some new questions about the cause of rabbit population fluctuations and the effects of these fluctuations on eagles and other predators. We’re seeing both a drop in the number of breeding eagles and an increase in the number of prey species showing up in the diet. We’re especially interested in finding out how habitat and human activities influence these results and how things will change next year.

I’m also anxious to compare our findings in the Bighorn Basin with a sister study site in Yellowstone’s Northern Range. This is the first year that Golden Eagle nests have been systematically surveyed there, and our colleagues in the Park have found more than twice the number of nest areas than expected!

Written By

Charles Preston

Dr. Charles Preston served as Senior Curator at the Center of the West and Founding Curator-in Charge of its Draper Natural History Museum and Greater Yellowstone Raptor Experience. He is now Senior Scientist and Curator Emeritus of the Draper Museum.