Whooo Helped At the Museum’s Hootin’ Howlin’ Halloween Event?

Halloween brings a special day at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. Suli, our turkey vulture, gets ready for it by carving her pumpkin, with a little help from Melissa, who adds starter holes to the pumpkin to get Suli started. This year Suli didn’t get into it as much as last year, but she did carve some rather nice eye lashes onto the eye openings. And yes, although turkey vultures feed almost entirely on carrion, they will also eat plant material, such as pumpkins, squash, coconuts, juniper berries, and grapes.

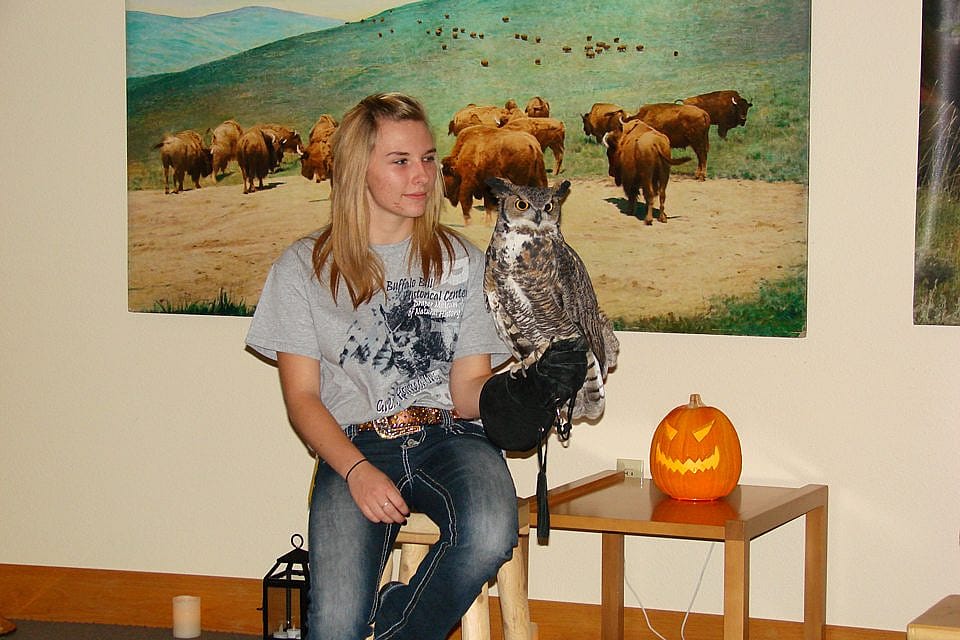

Suli spent her Halloween day showing off in the upper level of the Draper Natural History Msueum, where Melissa scheduled two talks. Teasdale, our great horned owl, spent his day in the lower level of the Draper section of the Center for the presentation of owl stories.

Teasdale’s Halloween day began when Jess went in to pick him up. He hopped, then hopped away again. He really didn’t want to go anywhere. Still, after a few hops he gave up, puffed his body feathers up to look extra fat, then relaxed his feathers, and grumpily waited as Jess dressed him with his jesses (leather leg straps) and leash. Upon arriving at our location, just outside the Draper Lab, where his handsome self would be on display during our owl stories, Teasdale slowly rotated his head to examine the lit jack-o-lantern behind him.

Owls can rotate their heads 270 degrees, as they have 14 vertebrae in their necks, twice as many as we do, so this is no big effort for him. He sees nothing particularly scary there. Teasdale does not get alarmed by many things. He checked out his current tree, who happened to be Jess. Melissa tells us that it is very likely that in his mind, we take the place of a tree, helping to camouflage him.

Teasdale was the frosting on the cake for the owl stories that Jordan and Gen read to the children who visited the museum for our holiday activities. Jess, Bill, and I took turns holding Teasdale and briefly talking about him between stories. Bill is our newest volunteer handler, and this was only his second time showing one of our birds in public. He did well, sitting in a relaxed manner, and enjoying his time with Teasdale.

Teasdale, showed little interest in the whole affair. Sometimes he would stare at the visitors, or stare at his handler, but often he simply ignored everyone.

As I sat, waiting for my turn with Teasdale, I hear a soft “Hoooo, hoooo, hoooo” behind me. I turned and saw a very small girl standing behind my chair. I softly said, “Good for you, that is one of the sounds that an owl makes.” I encouraged her to sit on the floor with the other child, but she shyly leaned against her mother. She probably just wanted to stay close to mom, but maybe, she wasn’t comfortable sitting next to a devil.

When Bill handed Teasdale off to me, Teas settled down, then s-l-o-w-l-y rotated his head and stared up at me. We made eye contact, and he stared so long at me, that I was the first one to look away. He then slowly turned his head to face the visitors. Halloween was no big deal for him, and the costumed children seemed no different to him than any of the other days he had spent in public.

Teasdale simply waits in his serious, quiet way for it all to be over, so that he can go back to his mew (room) where he will continue to quietly sit. After all, that is what owls spend a great deal of their lives doing in the wild. Even when the children came forward to receive their Halloween candy, he was unfazed by the whole thing.

After one story session, while Teasdale was standing on my glove, a number of the parents were quite interested in Teasdale, and asked questions. One person told me that they had an owl around them that looked just like Teasdale but was maybe a little smaller. She said he did not hoot, but rather made another sound more like a screech, and wondered if it could be a screech owl. It is true that screech owls have feather tufts upon their heads and coloring similar to great horned owls. The problem is that screech owls are substantially smaller than great horned owls, generally standing 7.5 to 9.8 inches in height, where as great horned owls stand 18 to 25 inches tall. So what did they see? Although the hoot is the typical sound that people think of, great horns may also make sounds that resemble a growl, as well as shrieks, beak snapping, hisses, and cat-like sounds. So based on the variety of sounds they may make, one can not rule out that the owl they saw wasn’t really a great horned owl.

At 4:30 p.m.it was time to return our birds to their mews where a scrumptious rabbit dinner was waiting for Teasdale. Of course he ignored it completely and settled down on one of his tree branch perches to continue quietly sitting. I am sure he was thankful, however, to again have his privacy. Dinner? That would be saved for later—after we all went home.

Question From a Visitor:

I noticed he (Teasdale) moves his ?ears? (said in an unsure manner) up and down. What is he doing?

I could not tell the visitor why he had put his ear tufts flat against his head, then raised them up. I did, however, tell her about these feathers that looked like ears to her. These are neither ears nor horns, but are simply tufts of feathers, called plumicorns or, more commonly, ear tufts. About a third of the owl species in the US have plumicorns. When in an upright position, they may help to camouflage an owl, by helping to break up the owl’s outline, and cause its head to look less round. Some researchers believe that the position of the plumicorns may be a way for owls to comminicate with each other. “So,” you might be thinking, “where did the term plumicorns come from?” In Latin, pluma means “feathers” and cornu means “horn.”

Written By

Anne Hay

Anne Hay has a Bachelor's degree in Elementary Education and a Master's in Computers in Education. She spent most of her working years teaching third grade at Livingston School in Cody, Wyoming. After retiring she began doing a variety of volunteer work for the Buffalo Bill Center of the West’s Draper Natural History Museum. Anne loves nature and has a concern for the environment. She believes that educating the public, so that they will have a better understanding and appreciation for the natural world, is very important. Because of this belief, volunteering at the Center is a perfect fit. She spends time in the Draper Lab, observing eagle nests for Dr. Charles Preston’s long-term research project on nesting golden eagles, writing observation reports of raptor sightings in the Bighorn Basin, and working with the Draper Museum Raptor Experience. Anne states that, “Having a bird on my glove, is one of my all time favorite things in life.”