Buffalo Bill and His Horses – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Summer 2013

Buffalo Bill and His Horses

By Agnes Wright Spring

In the acknowledgements of her book, author Agnes Wright Spring wrote, “I wish especially to acknowledge the assistance of James White, editor of Western Farm Life, who envisaged the story and gave me the assignment in 1948.” The Buffalo Bill Center of the West thanks Alice Beatty, Agnes’s niece, for loaning her copy of Buffalo Bill and His Horses (1935) for the excerpts that follow.

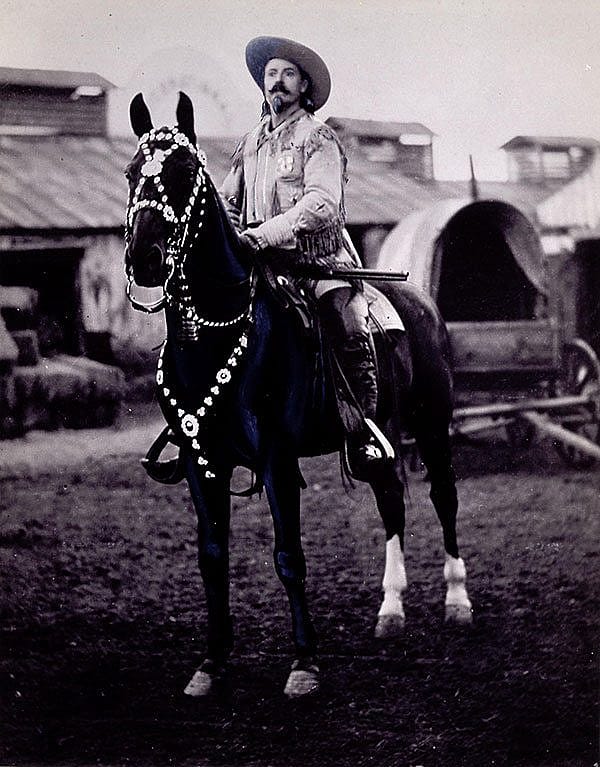

William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody was, above all else, a superb horseman with the horses linked to almost every phase of his life. Born in Iowa on February 26, 1846, Cody went with his family, by saddle, to the new western frontier called Kansas before he was eight years old.

When Cody was 10 years old, his father died, and Bill went to work for William Russell [as a teamster] in order to help support his mother. He began as a herder and had a small mule for a mount. Through hard work he rapidly advanced and in time became a wagonmaster.

After the Pony Express was inaugurated in 1860, Bill Cody, 14, became a rider [a fact often disputed by historians]. He made a name for himself for endurance as a carrier.

Later he joined the Seventh Kansas Cavalry, and then became a scout, guide and plainsman. From those early scouting days on, he was continually on horseback, except for a few years when he was playing in melodrama. He early mastered the accomplishment of riding bareback and leaping off and on his horse while the animal was galloping at full speed.

Brigham, a buffalo hunter

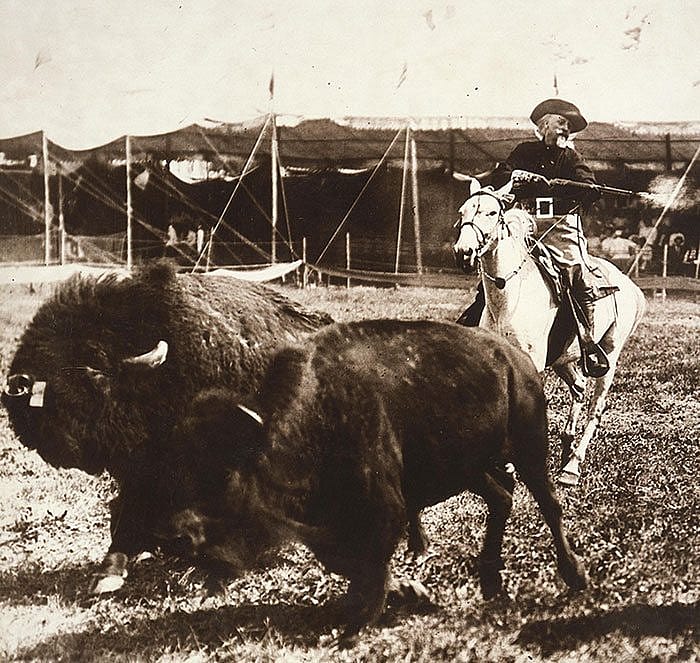

Brigham, a horse which Bill Cody obtained from a Ute Indian and named for the Mormon leader, was considered by him to be the best horse he ever saw for buffalo chasing. He called him the “King buffalo killer.” It was this horse that helped him to win the sobriquet of Buffalo Bill, which remained with him through life. He rode Brigham while he was hunting buffalo to supply the construction camps along the Kansas Pacific. Within seventeen months he killed, by his count, some 4,280 buffalo.

In the buffalo killing contest with Billy Comstock, one of General Custer’s guides, Buffalo Bill rode Brigham and dropped thirty-eight of the shaggy animals on his first run [compared] to Comstock’s twenty-three. His total score was sixty-nine against forty-six for Comstock. After the competition was over, Cody removed his saddle and bridle and riding Brigham bareback, guided the horse with his hand and knee into a herd of buffalo. Shooting from the horse’s back with his needle-gun, a breech-loading 50-caliber Springfield, which he called “Lucretia Borgia,” Bill Cody killed thirteen additional animals. When the Kansas Pacific suspended work in 1808, Buffalo Bill, then 22 years old, was out of work as a supplier of meat to the construction crews. In order to get money with which to take his wife and baby back to Leavenworth for the winter, Cody raffled off Brigham. Ike Bonham, holder of the lucky ticket, took Brigham to Wyandotte, Kansas, where the horse continued to hold his own in various contests of speed and endurance.

Buckskin Joe, the lifesaver

Rated almost as high as Brigham as a buffalo hunter was another Indian pony, Buckskin Joe, an army horse, which Cody rode on and off on scouting and hunting expeditions from 1869 to 1872. Although “rather sorry looking,” this horse was known all over the frontier as the greatest long distance horse of his day.

Old Buckskin was said to have been Buffalo Bill’s favorite on the trail when work was dangerous. Cody usually rode another horse and let Buckskin Joe follow along to be used for reserve in case Cody had to make a run for his life. Buckskin Joe instinctively scented danger and showed his fear at once. He was almost human in thrusting his head into the bridle and in standing still to be saddled. The longer the chase, the better the pony seemed to like it.

In the great buffalo hunt engineered by General Phil Sheridan and staged along the Republican River for Grand Duke Alexis of Russia in 1872, Cody permitted the duke to ride Buckskin Joe. Frank Thompson, a fox hunter of Pennsylvania, also shared this honor. Later, Thompson, who became president of the Pennsylvania Railroad, referred to him as “the most celebrated horse of the plains.”

Several times, because of his endurance ability, Buckskin Joe carried Buffalo Bill to safety from Indian attacks. One terrific ride, however, of 195 miles from the headwaters of the Republican River to Fort McPherson was too much for the loyal animal. The strain of the trip caused him to go blind. When in 1877, Buckskin Joe was condemned by the government and sold at public sale, Dave Berry of North Platte [Nebraska] bought him and gave him to Cody. Cody kept him at the ranch and cared for him until he died of old age. The horse was buried and a tombstone was erected over his grave which was inscribed:

“Old Buckskin Joe, the horse that on several occasions saved the life of Buffalo Bill, by carrying him safely out of range of Indian bullets. Died of old age, 1882.”

Tall Bull, a fast running horse

Among the best horses that Buffalo Bill ever possessed were Tall Bull and Powder Face. They were captured from Indians in 1869 during a fight under General Carr’s command at Summit Springs, Colorado.

Cody called Tall Bull “the fastest running horse west of the Mississippi.” He could ride Tall Bull bareback, and holding to his mane, he could jump to the ground and up again, repeating eight times. He won considerable money racing these two horses at Fort McPherson and nearby, until the army officers and others refused to compete with Cody.

Upon being summoned to Fort D.A. Russell near Cheyenne, Wyoming, as a witness at a court martial once, Cody was delayed for some time. In treating his friends while he waited for the trial, Cody spent the money which he had promised to use to buy furniture for Mrs. Cody. Finding himself without funds, he sold Tall Bull to buy furniture.

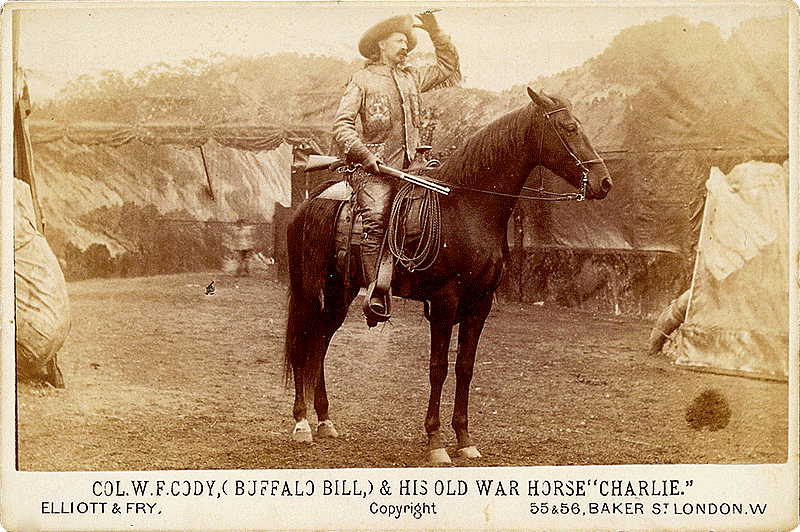

Charlie, almost human

Stranger and Charlie were two other horses which were Buffalo Bill’s companions in his scouting days. Charlie, a half-blood Kentucky horse, purchased for Buffalo Bill as a 5-year-old in Nebraska, was perhaps the most publicized horse of his day.

According to Buffalo Bill: “Charlie was an animal of almost human intelligence, extraordinary speed, endurance and fidelity. When he was quite young, I rode him on a hunt for wild horses, which he ran down after a chase of fifteen miles. At another time, on a wager of $500 that I could ride him over the prairies 100 miles in ten hours, he went the distance in nine hours and forty-five minutes.”

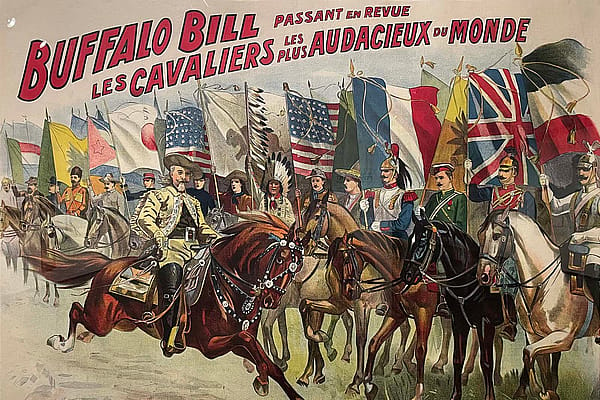

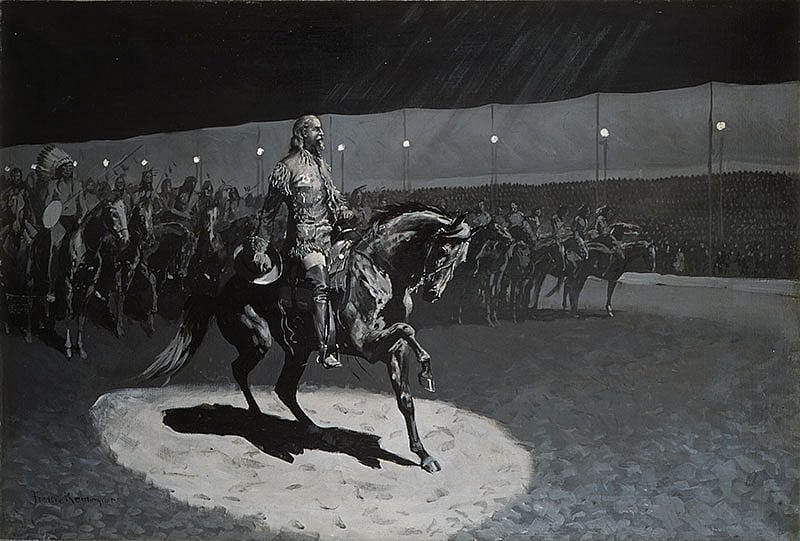

When the Wild West Show opened at Omaha in May, 1883, Charlie was the star horse, and he held that position at all exhibitions in this country and in Europe during the first season abroad, 1887.

In London, Charlie attracted so much attention that many members of royalty sought the favor of riding him. Among these was Grand Duke Michael of Russia, who several times rode him in a chase after Buffalo Bill’s herd of buffalo. When the Prince of Wales visited the show’s stables, he had the old horse stripped and examined him carefully. The Prince in speaking of his visit to the grounds, was quoted as saying: “I liked best looking at the mustangs””

[Upon Charlie’s death,] one of the London reporters wrote, “I saw Buffalo Bill’s horse, Charlie, 20 years old, a tame old gee-gee who licked my hand. Mr. Cody has ridden him upwards of 14 years in all his campaigns and western exploits.”

Charlie raced around the arena at the American Exposition grounds near London while his owner shot dozens of glass balls that were tossed up as turrets. The horse appeared to be at his best when Buffalo Bill rode him at the “command performance” at Windsor Castle.

But on the homeward journey to America, when the S.S. Persian Monarch was in mid-ocean, Old Charlie became ill and died. His death cast gloom over the entire ship. The carcass was taken to the main deck, wrapped in canvas and covered with an American flag. Members of Cody’s company and others assembled on the deck. Cody, standing alone near the lifeless form, is reported to have said in part:

“Old fellow, your journeys are over…Obedient to my call, gladly you bore your burden on, little knowing, little reckoning what the day might bring, shared sorrows and pleasures alike. Willing speed, tireless courage…you have never failed me. Ah, Charlie, old fellow, I have had many friends, but few of whom I could say that…I love you as you loved me. Men tell me you have no soul; but if there is a heaven and scouts can enter there, I’ll wait at the gate for you, old friend.”

While the band played, Old Charlie was allowed to slide slowly down skids into the waves of the Atlantic Ocean.

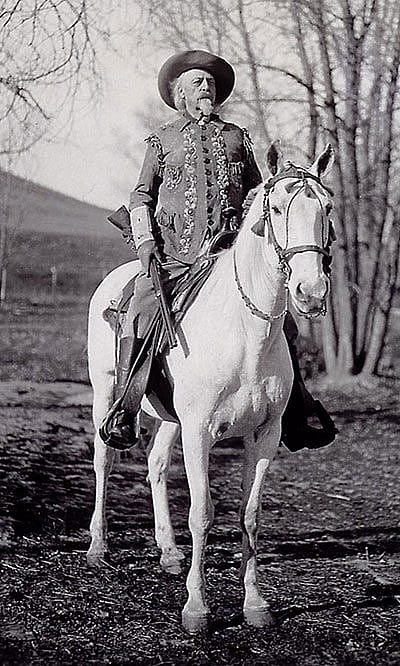

Rosa Bonheur paints Cody

It was during the season of 1889, while Buffalo Bill’s show was performing for the Great International Exhibition at Paris, that Rosa Bonheur, world-famous artist, spent many hours at her easel in Cody’s camp. There she painted her well-known picture of Cody on his “favorite” white horse, whose name is said by one authority to have been Tucker; by another, McKinley.

Prints of the picture were sold throughout the United States and Europe. The original painting was sent to Cody’s home in North Platte, then called “Welcome Wigwam.” It is reported that when Cody later was notified one day that his house was burning, he telegraphed to Nebraska as follows: “Save Rosa Bonheur’s picture and the house may go to blazes.” [The painting is now in the Buffalo Bill Center of the West’s Whitney Western Art Museum.]

Billy dropped dead

After the Colonel’s horse Old Charlie died, one of Charlie’s companions, a white horse, took his place. This was Billy. His picture was placarded on walls and exhibited in windows all over the land. Billy probably appeared in more cities and before more persons of distinction, rank, wealth, and character than any of Cody’s previous mounts.

Singularly enough, it was on the return from the second triumphal tour of the Wild West show in Europe in 1892 that Billy, without any premonitory symptoms of sickness, walked off the gangplank of the ship, neighed as his hoofs struck his native shore, and dropped dead.

Duke, a magnificent horse

One of the most beautiful horses which Buffalo Bill ever owned was Duke, a magnificent chestnut, a present from General Nelson A. Miles. In 1898, on the day set aside as Cody Day at the Trans-Mississippi Exposition at Omaha [Nebraska], Cody, mounted on this splendid animal, led his show parade. Twenty-four thousand persons stood and cheered. Duke was known to audiences all over the country in the early 1900s.

“Farewell tours”

While the Wild West was playing on the Continent about 1905, glanders [an infectious disease primarily in horses, mules, and donkeys] broke out among the horses in the show. Little or no publicity was given to the fact that approximately three hundred fine animals, including racers, buckers, and Percherons belonging to the Show had to be shot. This was a severe jolt to the men who had come to know and love the horses.

About this time Cody began to make final “farewell tours,” with the hope that he could retire to his Wyoming ranch near Yellowstone National Park to spend his last days in the great outdoors. But his mining and other ventures did not pay off. He was constantly in need of money and more money. It was therefore necessary to repeat many of his “farewells.”

In August 1913, the failure of Cody’s old Wild West Show was announced to Denver’s public by the staccato rap of a whipstock and the whir of a buckskin thong-lash wielded by George Colliding, auctioneer for United States Marshal Bailey.

As the spieler, E.R. “Kid” Austin, ballyhooed and beat a tattoo on the rostrum with a cane—horses, camels, mules, sacred cows, and band wagons went under the hammer.

The most determined bidder of the day was Colonel C.J. Bills, who had come all the way from Lincoln, Nebraska, just to bid on a white horse named Isham. To some, the horse was just a “flea-bitten nag,” but to Bills, he was the most desirable animal on the lot. Isham had carried Buffalo Bill around the arena in many a show.

Slowly the bidding crept up—and then—Isham was “sold to the gentleman from Lincoln” for $150. Bill’s mission had been successful. He shipped Isham up to the TE Ranch in Wyoming and gave him to Buffalo Bill “for keeps.”

But soon after his Show was closed, Cody spent many strenuous hours in the saddle in a last supreme endeavor to recoup his losses by promoting a motion picture. This picture he hoped would depict the Indian troubles at the time of the Wounded Knee battle in 1890. In that undertaking, he undoubtedly overtaxed his strength…

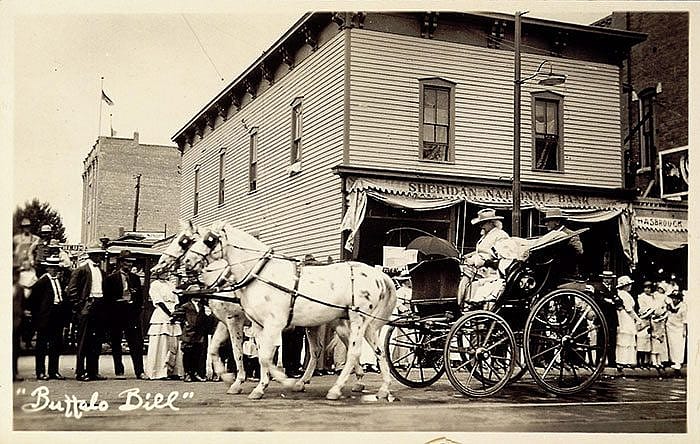

Cody, however, took to the road again with the Sells-Floto Circus. He greeted the great audiences under the white top from his saddle. But he was forced, because of his waning strength, to lead the parades as the driver of a team of white horses hitched to a phaeton.

Even so, he was still a striking figure as he skillfully “handled the ribbons.” Cody often said, “Back in 1870 I could drive any horse that ever had a bit in his mouth and a lot that hadn’t.” And he could drive just as well in his later years as in his youth.

A bronze rider scouts on

In 1922, Smokey, a favorite horse of Buffalo Bill, was shipped from the TE ranch on the South Fork of the Shoshone River in Wyoming, to the New York City studio of Mrs. Harry Payne Whitney, to be used as a model for a statue. The sturdy equestrian statue fashioned by Mrs. Whitney now stands on the edge of the little Wyoming city that bears the name of Cody. There in the shadow of the peaks where Buffalo Bill loved to hunt and to entertain his friends, a spirited bronze horse, on a great granite base, carries in his saddle a bronze rider who is scouting trail.

About the author

Born in Colorado and raised in Wyoming, Agnes Rebecca Wright Spring (1894–1988) was a noted historian and prolific writer, publishing dozens of books and short stories, and hundreds of articles. She held positions in the state governments of both Wyoming and Colorado, and was inducted into both the National Cowboy Hall of Fame and National Cowgirl Hall of Fame. She was director of the Wyoming Federal Writers Project during the Great Depression, was women’s editor for the Wyoming Stockman-Farmer for twenty-seven years, and received lifetime achievement awards from the University of Wyoming and Western Writers Association.

Post 001

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.