Past Exhibition: Developing Stories: the Photography of James Bama

Past Exhibition

The Buffalo Bill Center of the West knows that western art enthusiasts are sure to recognize the work of James Bama. After all, he was a prolific artist, detailing the West with his realistic paintings. But few have had a chance to view his photographs.

On view in 2014 and 2015 in the Center’s Kriendler Gallery on the mezzanine level, Developing Stories: the Photography of James Bama featured more than 65 photographs and sketches by Bama. The Center’s Emily Wood, Curatorial Assistant for the Whitney Western Art Museum, curated the exhibit.

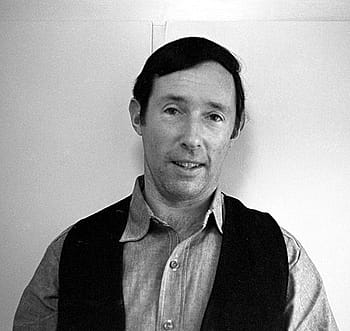

“Jim Bama is the first to say he is not a western artist,” Wood says. “Born and raised in New York, he became a successful advertising and book illustrator. But, at the age of 40, he left commercial art to pursue his own paintings and moved to Cody, Wyoming in 1968. The risky move paid off, and since then, he’s received high praise as a painter of western American subjects. His photos, though, are the first stage in his storytelling—capturing personalities, lifestyles, and his own outlook on the world, which are enhanced and refined into finished paintings.”

Photography was a necessary tool for Bama, “like a saw or a hammer is to a woodworker,” he explains. During many of his photo sessions, he positioned people to capture the best lighting, pose, and background. He took thousands of photographs, but only a few ever became paintings.

“Despite his reliance on photography as a reference, Bama does not consider himself a photorealist,” wrote Thomas B. Smith, Director of the Denver Art Museum’s Petrie Institute of Western American Art, in 2007. “His intention, he argues, is not to recreate photographs, but rather to render his subjects with photographic precision.”

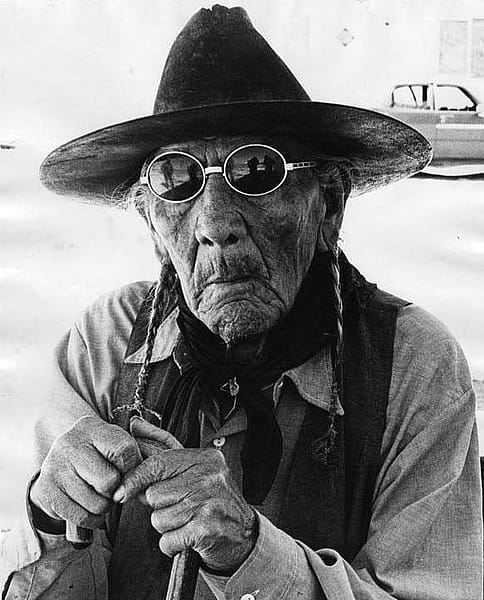

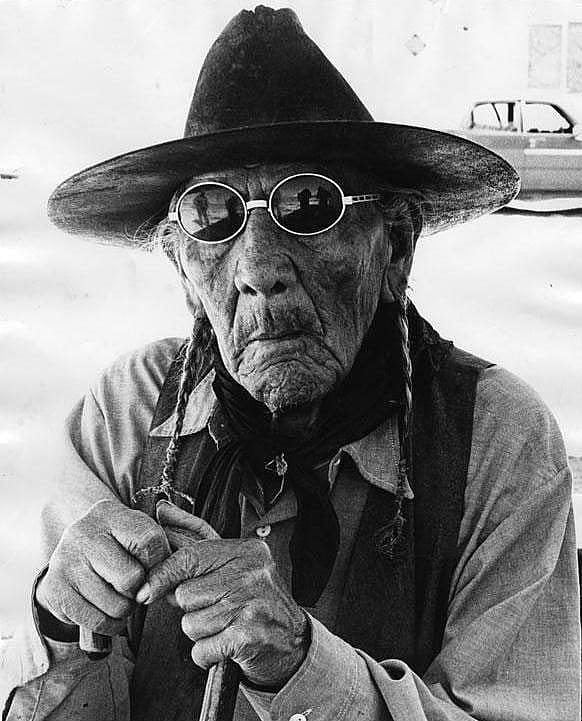

Bama is an artist attracted to real people—to their stories, their colorful lives, and their ability as models to call up the past. He likes faces that show signs of character, beauty, attitude, and age. His portraits—and photographs—feature the likeness of a person, as well what they symbolize. As he put it, “Successful people are not nearly as interesting as people that are fighting the battle of life.”

Read more about Bama in the western art pages of our website.

From the Exhibit

Developing Stories: The Photography of James Bama

“I use the West…as a vehicle to say what I want about life.” —James Bama

James Bama is the first to say he is not a western artist. Born and raised in New York, Bama became a successful advertising and book illustrator. But at the age of 40, he left commercial art to pursue his own paintings and, in 1968, he and his wife, Lynne, moved to Cody, Wyoming. The risky move paid off. Bama has since received high praise as a painter of western American subjects. His photographs are the first stage in his storytelling—capturing personalities, lifestyles, and his own outlook on the world, which he enhances and refines into finished paintings. We invite you to trace your own experience of the West through Jim’s lens.

“I’ve always felt photography was a necessary tool, like a saw or a hammer is to a woodworker…” —James Bama

As a tool, photography was essential to expanding Bama’s range of subjects and compositions. during many of his photo sessions, he positioned people to capture the best lighting, pose, and background. The photographs reflect carefully composed formal elements such as line, texture, light gradation, and space. Bama took thousands of photographs, but only a small portion ever became paintings. Although his paintings resemble their humble black and white beginnings, they are complete creations unto themselves—refined, inspired, symbolic, and idealized.

“Successful people are not nearly as interesting as people that are fighting the battle of life.” —James Bama

Bama is an artist attracted to real people—to their stories, their colorful lives, and their ability as models to call up the past. He likes faces that show signs of character, beauty, attitude, and age. Bama approaches his models at events, on the street, or through other people. Many are longtime Cody residents. His photographs capture poverty, ruggedness, pioneer spirit, pride, and a host of other states. In his portraits, Bama shows a person’s individuality, as well as what they symbolize. By including symbolism in his works, Bama believed he could make a stronger statement about life and connect his subjects to a larger audience.

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.