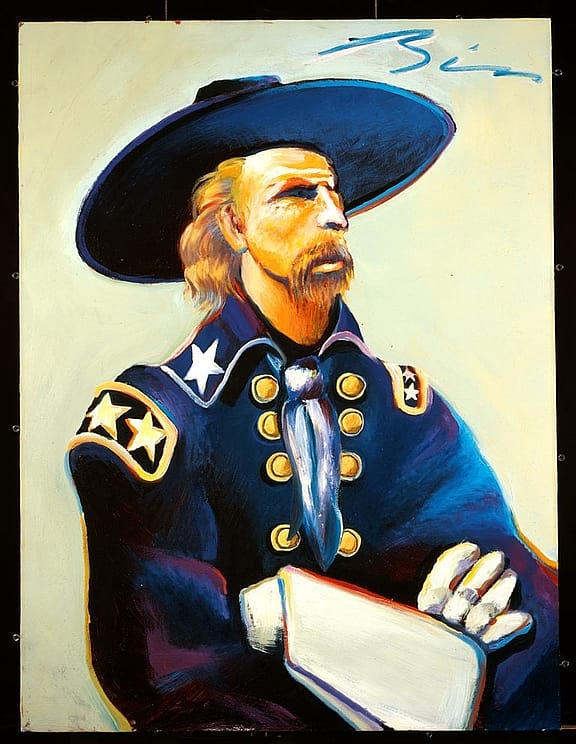

Custer: “Bound for glory”

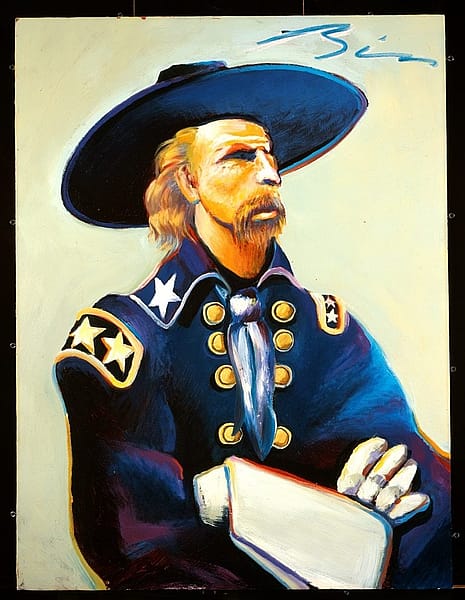

“On to Little Big Horn for glory,” George Armstrong Custer (December 5, 1839 – June 25, 1876) announced in June 1876. “We’ve caught them napping.”

Napping indeed. The battle was over in “as long as it takes for a hungry man to eat his dinner,” according to Two Moons, a chief of the Cheyenne. U.S. casualties at “Custer’s Last Stand” were 268 dead and 55 injured. Depending on which historian you read, the number fielded by the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho forces against the Seventh Cavalry along the Little Bighorn River in Montana, June 25 – 26, 1876, is somewhere between 1,000 and 2,000 individuals.

And to think that Custer once envisaged, “There are not enough Indians in the world to defeat the Seventh Cavalry.” He also said, ‘Numerical superiority is of no consequence,” and, “In battle, victory will go to the best tactician.”

My brother and my oldest grandson visited Hardin, Montana, last month to view the annual Custer’s Last Stand Reenactment. Then, we traveled over to the Little Bighorn National Monument, where I wondered, “How did this happen?” I like how author Guy Vanderhaeghe (A Good Man, 2012) writes of the impact of Custer’s defeat:

News of the disaster at Little Bighorn reached the Eastern Seaboard shortly after July 4—and not just any ordinary July 4, but the grand celebration of the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Republic. A country feeling its oats, flexing its muscles, vigorous and rich, cocksure and confident, has seen the impossible happen, the unthinkable become fact. Sitting Bull has spoiled their glorious Centennial, pissed on Custer’s golden head—the head of a genuine Civil War hero, the head of someone who has recently been touted as a future President of the United States. Somehow a wedding and a funeral got booked for the same hour in the same church.

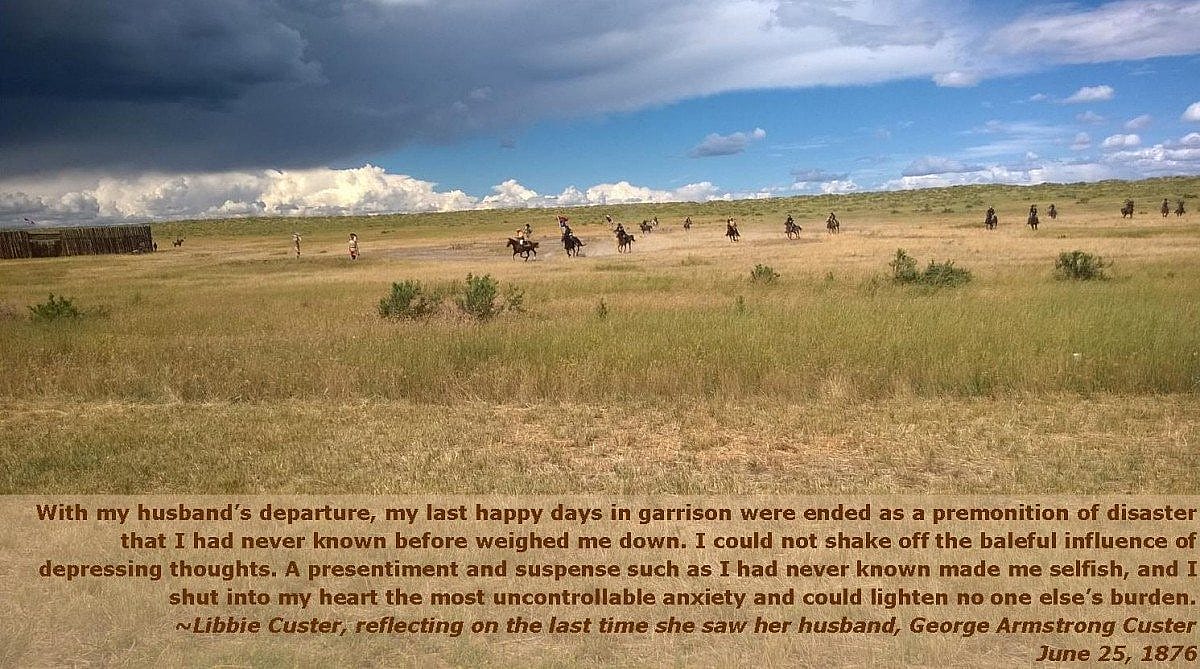

Custer Battle Reenactors, Hardin, Montana, 2014

L–R: Eric Jackson House samples hardtack with 7th Cavalry Interpreters before the “battle;” Libbie Custer arrives in a buggy; the 7th Cavalry lines up to overrun the Indian village; the aftermath with “bodies where they fell.”

As that summer day ended, I looked across the expanse of the battlefield and peered up at the monolithic memorial to the 7th Cavalry. It remains a sentry over the mass grave of fallen soldiers. This solemn place reminds me once again that the battles, the people, the triumphs, trials, and experiences of the American West really do transcend place and time…

Written By

Marguerite House

Marguerite House served as the Center of the West’s Acting Director of Public Relations until her retirement at the end of 2018, and as editor of its member magazine, Points West, through May 2019. Following a seven-year stint as Business Manager for the Cody Country Chamber of Commerce, Marguerite moved “across the street” to the Center in 1999. She then held five different positions in three of the Center’s four divisions, landing in PR in 2005. “I think that [gave] me all kinds of perspectives for our readers,” she says. She enjoys writing (especially a weekly column for the local newspaper called “On the House”), cooking, and spending time with her six grandkids.