Buffalo Bill’s Wild Cowgirl Falls in Love – Points West Online

Originally published in the New York Journal, April 3, 1898

and in Points West magazine, Summer 2010

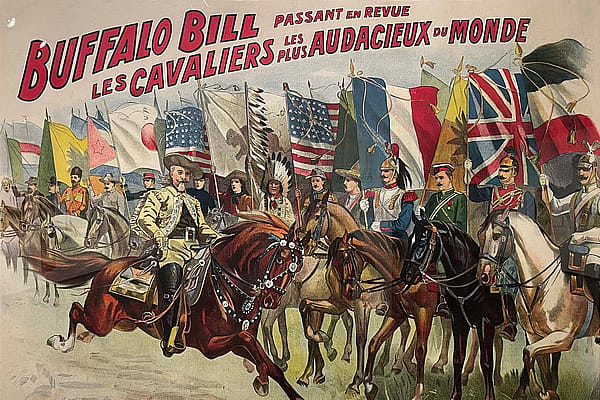

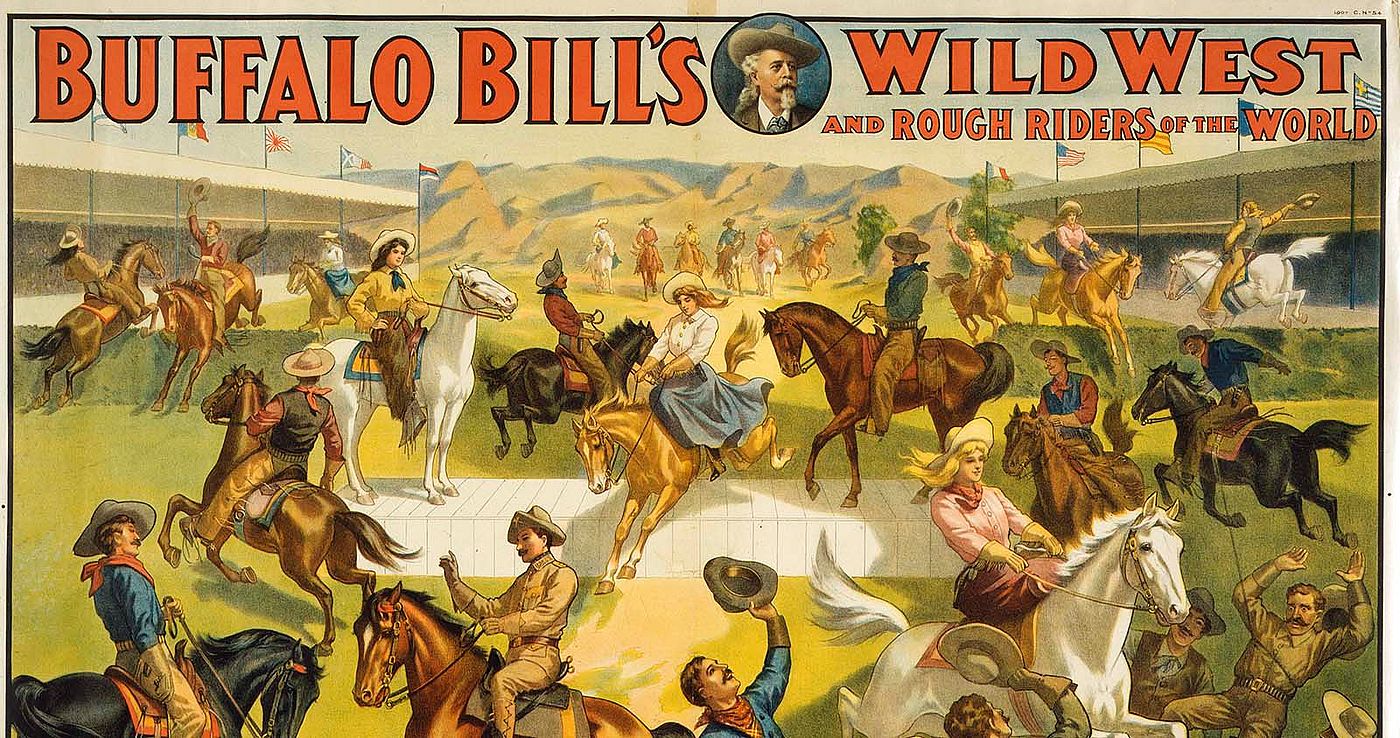

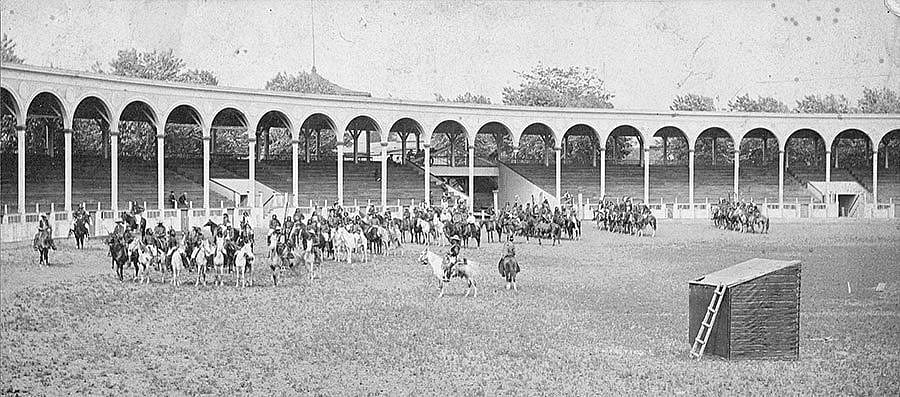

A Romance of the Congress of Rough Riders in Madison Square Garden

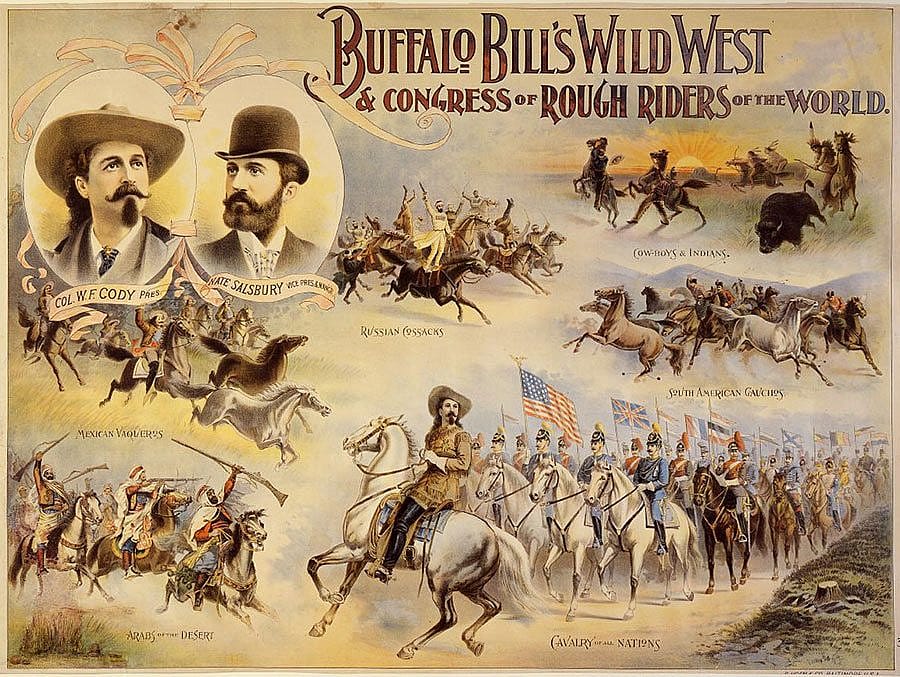

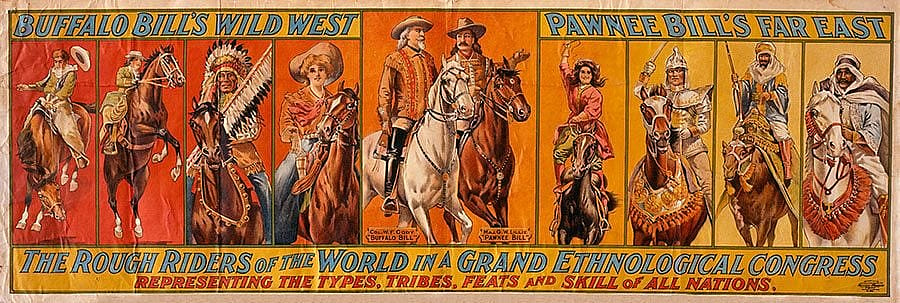

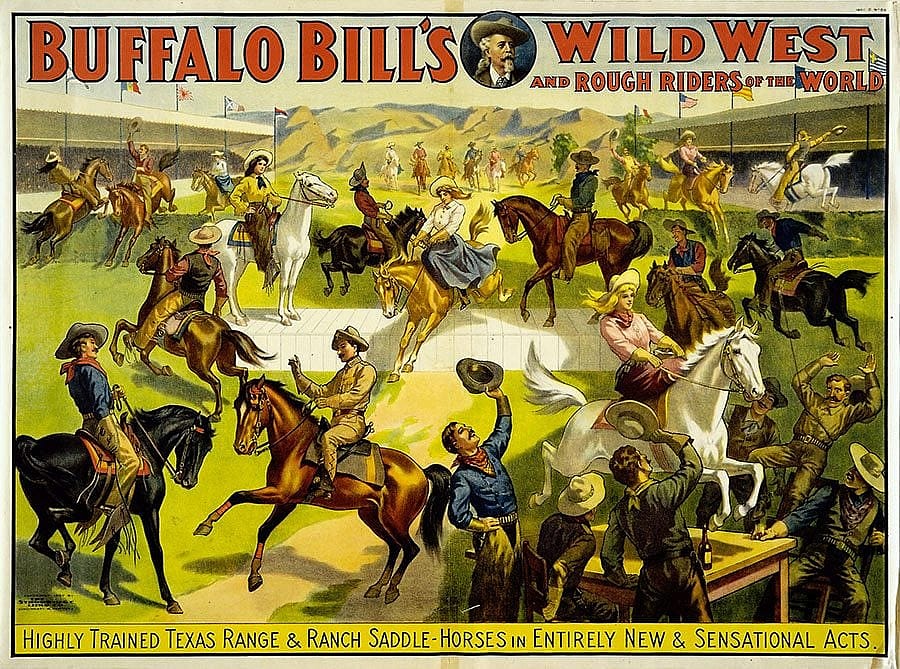

A romance is budding amid the dust and tanbark of Colonel Cody’s Wild West Show and Congress of Rough Riders.

It is a story of how Venus followed in the wake of Mars and proves that if young people of marriageable age and personal attractions discuss the Cuban situation, heart complications are likely to follow.

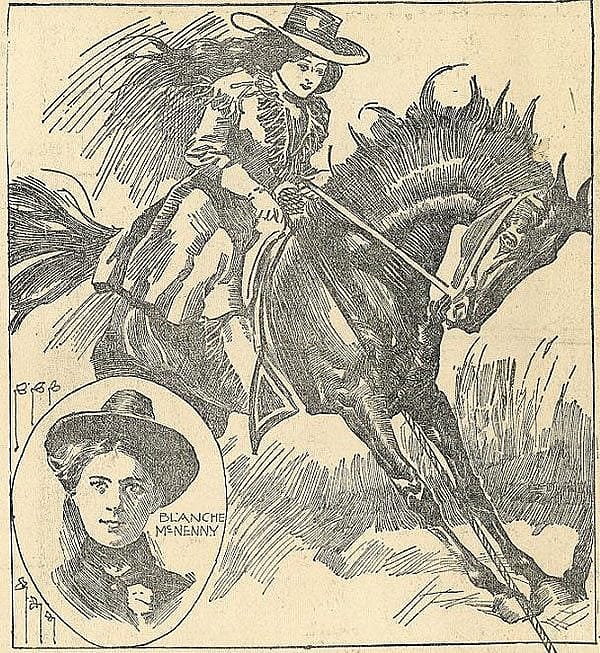

The hero of this tale of patriotism, rough riding and hearts is handsome Sergeant Hugh Thomason, U.S.A.; the heroine, winsome Blanche McKenny, the queen of the cowgirls. Both are members of Colonel Cody’s Congress of Rough Riders.

Sergeant Thomason is young, brave and ambitious. Miss McKenny is young, attractive and worldly. Both are favorites of the gallant Colonel, and both had heard much about each other before their meeting two weeks ago. Each was distinctly interested in the other before and on sight.

They met on the tanbark one evening before the performance at Brooklyn.

The Sergeant doffed his cap. The cowgirl looked up at six foot two inches and smiled engagingly. The first two minutes they talked of the weather and show business. The next two, they told each other why they were with the Congress of Rough Riders.

The Sergeant desired opportunities for travel. The Western girl wanted to raise her record of horsewomanship by a season or two of emulation of the gauchos and other wild riders in the Colonel’s “aggregation.”

Then they fell to talking of the suffering Cubans. The Sergeant noted that Miss McKenny’s hazel eyes filled with tears at the thought of the wicked reconcentrados. He liked this. Men don’t like to be deluged in tears, but not one among them but likes to see the soft moisture of pity in Beauty’s eyes. He denounced President McKinley’s dilatory policy. She said all the bands in the United States should gather about the White House and play “Yankee Doodle” for the President’s inspiration.

The Sergeant remarked that Governor “Bob” Taylor of Tennessee had promised to make him a colonel in the event of a war with Spain.

“Will you go?” demanded the girl.

“Go?” The soldier folded his arms and looked upon her from his lofty height. “Do you take me for a coward? Of course I’ll go.”

Miss McKenny clapped her hands: very small, well-manicured hands they are, though they have handled a lasso, shot wolves, and guided bronchos.

“And I will”— [she said.]

Miss McKenny made an offer on the spot. Not an offer of marriage. She is very conventional in her view of matrimonial advances. The especial pride of her riding stable is a magnificent chestnut whose title, Jay Grego, may be found registered in Bruce’s stud book. Miss McKenny said she would give Jay Grego to the Sergeant if he went to battle with the Spaniards.

“I will ride Jay Grego at the head of my regiment,” he promised.

“And I will have my hair cut close, wear a boy’s suit and ride Jay Grego’s sister to battle,” said Miss McKenny.

The soldier and the cowgirl clasped hands. Sergeant Thomason’s clasp must have been excessively cordial, for when the girl of the plains drew her hand away blushes chased each other over her cheek and brow.

The young people have sought each other’s society on every conceivable pretext since they made the compact. Miss McKenny violates discipline by looking over her shoulder at the following squad of cavalry when she rides in the grand entrance and exit of the show. “I do so admire soldiers. My father was a soldier,” she says.

Every one else in the Wild West Show and Congress of Rough Riders smiles in approval. The married members smile reminiscently, the unmarried anticipatingly. Sergeant Thomason and Miss McKenny are furnishing the romance of the Wild West season.

The queen of the cowgirls is tall and slight. Her figure sways like a reed under a blowing wind. Her face is a pure oval with a youthful roundness of the cheeks and of a healthful red-brown tint, framed in dark brown hair, which though fastened in a net when she rides, lets a few insurgent ringlets wander out upon her forehead.

Her features are delicate and regular. The face might escape notice in a crowd were it not that a pair of mischievous, restless hazel eyes challenge attention. An alertness of expression, like that of the trained soldier, marks this young woman, and she walks with a free, gliding motion suggestive of the boundless liberty of her Western prairies. She has small, white, well-kept hands, and the slender feet of a patrician damsel. From the vast silences of the prairies, where the wind whispers over its grasses, she has brought a voice as low, as sweet, as correctly modulated as you could find in any drawing room.

She was educated in the public schools of Kansas, and an Illinois university. That training was supplemented by the broad, inspirational culture of the plains. She sings prettily in a clear, flutelike soprano. She is an accomplished pianist. She embroiders. She would make an excellent housewife. She can broil kidneys.

In the late seventies, a soldierly figure might have been seen cantering across the plains to one of the primitive sod houses of Western Kansas. After a ride of twenty miles, he alighted carefully, drew something soft and white and weakly protesting from beneath his overcoat, and showed it to two elderly ladies who came from the house to meet him. The rider was A.C. McKenny, one of the most brilliant cavalrymen of the late war, and the soft, protesting bundle his five-week-old daughter Blanche, whose infantile charms he displayed with pride of her grandmother and great grandmother.

And so her career as a rider began. She was bred and all but born in the saddle. Her passion for horses is inherited from the dashing cavalryman, her father.

“I have been Pa’s jockey ever since I can remember,” she says.

A hundred-mile ride on the windswept plains of her native Kansas is nothing for this girl. Once she was leading five horses from Republic, Kansas, to Superior, Nebraska, distant from each other a hundred miles. She was driving in a light buggy. A horse was fastened to either side of the harness of the horse she was driving. Through the back window of the buggy she drew the halter reins of two others, and the fifth horse’s halter rein was fastened to that of one of the horses in the rear. A snow storm overtook them and the girl lost her way at night. She tied the horses so they formed a living barricade, and wrapped in buffalo robes, slept under an osage orange hedge.

She has lassoed and tamed wild steers.

She has killed many a skulking wolf of the plains and has nine snapping wolf cubs at home as pets.

Many a jackrabbit hunt has she organized, and in one hunt, killed thirty-six of the long-eared, fleet-footed animals.

She has killed more rattlesnakes than she can count by a blow from the stock of her riding whip. On the wild vastness of her Kansas home, this girl is fearless. She confesses to having had a tremor or two in New York.

She’s afraid of trolleys.

“I am not afraid of horses nor wolves nor Indians. You cannot produce anything that I am afraid of in the West,” she says. “We are safe under God’s protection there. Here all you seem to have is police protection.”

Miss McKenny and her fair companions, Miss Lizzie Williams and Miss Mabel Hackney, have lived in the sod houses of the frontier, made of layers of fresh sod instead of bricks, and with straw- and sod-covered roofs. They have known the thrill produced by the ominous warning of a rattler that glided snakily in upon the ground floor of their homes, and once one of them found a snake crushed beneath the mattress of her bed where it had crawled for warmth.

Miss McKenny wears the gold medal of the world’s championship as a long distance rider. She won this distinction in Pittsburgh two years ago when she rode twenty miles in thirty-eight minutes, changing horses every mile, and then, as she puts it, “having time to spare.”

Two years ago, Miss McKenny was the rage of Omaha society. Colonel Cody gave a reception for her in the Nebraska metropolis after she won the world’s honors as a long-distance rider. Society went in obedience to curiosity. It stayed until the hours set for the reception were long passed. They saw a lovely young woman in white, filmy evening gown; a brilliant but modest young woman, who rumor said had a stock ranch of 320 acres, a stable full of race horses, one of which was valued at $20,000. It [society] was fascinated. Invitations to the most exclusive functions rained upon her. She accepted some and refused some of them, but did both with indifference. She was stifled in the city. She pined for the broad spaces of her home on the ranch, for the music of her horses’ neighing, and she fled.

“We went to some of the stores yesterday with a lady who wanted us to be impressed,” said Miss McKenny. “We were sorry to disappoint her, but we were really not impressed at all. There are great stores in our beautiful West, a fact of which she did not seem to be aware. We dined with her at the Waldorf-Astoria. It was a beautiful hotel, but do you know what I thought while I was there? The big hotel owes its beauty to the fact that it reminds us of nature. There are the marble and granite for instance, and the palms. We can see marble and granite in the quarries of the West, and it seems more beautiful to me there.

“Oh, I wouldn’t live in New York for worlds! Why, even the wares in the great stores are dirty. You don’t see accumulations of dust and soot in the stores in the West!

“It is filthy underground here, filthy above ground, and filthy even where the buildings extend almost into the skies.

“On the rolling meadows of the West land, one scents only the perfume of new-mown hay and the odor of the fresh wildflowers growing in profusion along the clear rivers. Here you have the dirty streams flowing sluggishly to the sea, bearing garbage and disease upon their bosoms. There are no fields of tall grass, no rocks and crags, no stately forests from which blow pine-scented breezes. It is all so artificial and handmade. Even the women and the men seem unreal and unnatural. They live on luxury. They pander to their appetites alone.

“When we dined at the Waldorf-Astoria, the lady who took us about asked us to have a cocktail. We were horrified. I have never drunk intoxicating liquor in my life. I never will. She told us to notice how many of the ladies were drinking cocktails and champagne, and I thought: ‘The Waldorf-Astoria sheltered a good deal of sin, for where there is liquor there is intoxication, and where there is intoxication there is sin.’

“I have seen the saddest and most shocking sight in New York I ever saw in my life. Looking from our window in what is said to be the heart of New York, I saw a woman drunk and reeling. You could not see a sight like that on our beautiful prairies.

“Cities must scramble to come up to Denver and Omaha!”

The spectacle of the drunken woman haunted this girl who had herded and branded her own cattle, and mounted and tamed fiery broncos and wild steers that would brook no touch but hers. She returned to it:

“Oh, when I saw the drunken woman I could not keep back the tears of sympathy,” she said. “But when I saw the women drinking at the hotel, I had none. I saw that it was the beginning. The drunken woman may have besotted herself to drown bitter memories, but those well-dressed women should not have bitter memories.

“I do not even admire your women. They seem to me as wooden as the dummies in the show windows.”

And pretty Mabel Hackney, cousin of the Younger brothers, bandits, and gentle Lizzie Williams, who is one of the famous riders of the West, and who owns 620 acres of land and a stable, including the finest filly west of the Mississippi, nodded assent.

Such is the heroine of the Wild West romance.

The hero is tall, and straight as an Indian, blue-eyed and fair-haired, with the bronze of the West on his face. He is a graduate of the Michigan Military Academy. At one time he was the youngest sergeant in the United States service. He has been stationed at Fort Wingate, New Mexico; Fort Niobrara, Nebraska; Fort Lewis, Wyoming; and Fort Myer, Virginia. He showed much valor in the field against the Navajos and Apaches. He left Troop F, of the Sixth United States Cavalry, the “Gallant Sixth,” to see the world, which travel opens. He has all the bravery of his native Tennessee county, which sent out the Eighteenth Tennessee, said to be the bravest regiment in the Confederate Army.

He longs for the opportunity a war with Spain would afford to men such as himself. Granted that opportunity and he will ride in the front of battle on Jay Grego, Miss McKenny’s pride of horses.

And if he returns, the Wild West show people believe he will receive the sweetest of rewards—Blanche McKenny’s charming self.

Sidebar: Separate lives—the soldier and the cowgirl

By John Rumm, PhD

Romance, alas, is often fleeting and short-lived. The courtship of Blanche McKenny and Hugh Thomason, though rich with promise, proved unrequited: the relationship ended when Thomason left to serve in the Spanish-American War, and both moved on with separate lives.

According to veteran cowboy Billy McGinty, a “rough rider” with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders during the late 1890s, Miss McKenny “used to have her own show in which she was billed as the woman rider of the world’s highest jumping horses.” While with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, he recalled, she met and subsequently married Lem Hunter, another rough rider. The couple then started their own show, the “Blanche McKenny and Hunter Racing Combination,” and McKenny later became “a good horse trainer” and a noted breeder according to Oklahoma Rough Rider: Billy McGinty’s Own Story, a book edited by Jim Fulbright and Albert Stehno.

Although Hugh Thomason’s name does not appear in the surviving rosters for Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, he was undoubtedly the same Hugh Thomason, a native of Nashville, Tennessee, who attended Michigan Military Academy, graduating as an “Honor Man” in 1895. While there, he was a classmate of Edgar Rice Burroughs, author of the “Tarzan” adventure novels. In a letter to his old chum on November 13, 1929, Thomason summarized his post-graduation career:

When I left the Academy, I joined the Sixth Horse at Fort Myer, Va., and was made a noncom at once. I went up for a commission and failed miserable in geometry. Quit the army and rode a year with Buffalo Bill. Went to Cuba and joined the Army of Maximo Gomez as a captain of artillery. When the Spanish war was over, I went to Venezuela as a Lieut. Colonel in command of the Foreign Legion. When our president was overthrown (Anrade) by Cipriano Castro, I was captured and came within an ace of facing the firing squad.

After a series of other exploits in the Philippines and South Africa, Thomason returned to the United States in the early 1900s and went back to Michigan Military Academy where he became Acting Commandant and head of the Cavalry Department. He left in 1907 after being appointed as a Chief Petty Officer with the U.S. Navy in 1907 and retired from active duty in 1927. Thomason was married and had at least one child, a son, Hugh DeWitt Thomason.

Transcriptions of Thomason’s correspondence with Burroughs, edited by David Bruce “Tangor” Bozarth, may be found at www.erblist.com/bfs/thomason.shtml.

John Rumm is the former Director of the Curatorial Division and Curator of Public History at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West.

Post 071

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.