I Solemnly Swear That I Am Up To Cataloging

When I tell people I manage the Corporate Archive Blueprints for the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, they immediately assume I am Harry Potter with the Marauders Map and I know interesting secret passage ways into the building. Alas, I have yet to find a Room of Requirement, the One-Eyed Witch Passage or moving magical footprints on any of the blueprints. I did come across one print that fell victim to a mischievous cat, which the evidence is clearly shown in the little red paw prints across the paper. Throughout my internship, it has been interesting to carry out the tasks that come along with processing an archival collection, but also learning about the Center’s architectural history.

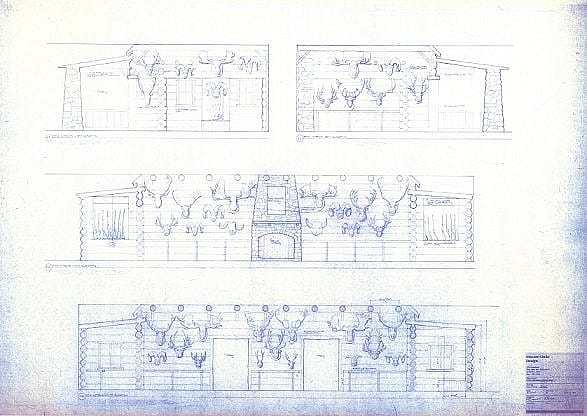

The archive has a range of plans including construction, furniture design, landscaping, plumbing, electronic, maintenance and special exhibitions. I am physically organizing, inventorying, scanning and cataloging over 10,000 of these blueprints. At the beginning of this project last year, the one thing that struck me when entering the storage vault was the vast amount of blueprints. Every container, box, nook and cranny I looked in and under was hiding a blueprint, waiting for a glimpse of humanity again. My first plan of attack was to organize these prints chronologically and house them in new flat file map cases. One has to be careful when handling the older prints because they are either delicately drawn with graphite on thin tracing paper or have become brittle over time because of the deteriorating metallic-chemical compounds used in their blue-paper’s creation process. The next step in my project involves using a spectacular 56 inch long scanner to convert these blueprints into digital form, while I am cataloging each print at the same time. Although these blueprints are saved on the Center’s database, I should explain that they are only accessible for internal use, in other words they are not open for public viewing due to security and confidential reasons.

As I continue to sift through the archive’s blueprints, it is clear that the evolution of the Center’s building structure has grown based on the visitors and staff’s needs and economics of the time. The earliest blueprint I have found dates back to November 1923, which depicts a survey or detailed map of the site and surroundings for the Buffalo Bill Memorial, aka The Scout or as written on the blueprint, “Cody Equestrian by Mrs. [Gertrude Vanderbilt] Whitney”. Other blueprints show the Museums, theater, shops, studios and lodges separated by different buildings, parking lots or courtyards. Even the types of blueprints within the archive have evolved as well. Precisely drawn with the aid of technology and reproduced on white paper, the most current archive prints date to the early 2000s, depicting structure plans and display views for the Draper Museum of Natural History. It is fascinating to see within these plans the Center’s relocation, eliminations, expansions and change of names; some of which can still be found today.

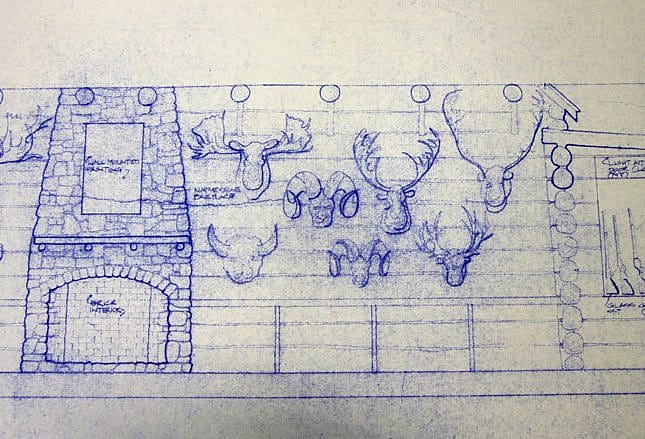

These blueprints are not just a historical record of the Center’s past; they stand for how we can design a deeper engagement between human interaction, space and object. I love the prints that have been revised, highlighted and drawn over to find what the best interest is for the Center’s future. One of my favorite blueprints is a drawing for the “Hunting Lodge” in the Cody Firearms Museum, depicting walls of mounted animal trophy heads. I appreciate this print’s personal touch and devotion to detail. It illustrates the quality of the designer’s original intention to connect with viewers who want to experience a part of the West.

Now that I am in the process of converting the Center’s archival blueprints into digital form, I am able to continue cataloging them offsite in order to resume my education. Using this technology is as good as any magical charm I can think of. Although it is going to take a while to complete the entire project, in the end however it is worth preserving this hidden history.

Written By

Corie Audette

Corie Audette is from Loveland, Colorado, and is currently the Records Management Intern for the McCracken Research Library. She has an Art History, Liberal Arts and Fine Arts degree, and will complete her Museum Studies graduate degree from Johns Hopkins University in December 2015. Beyond cataloging and organizing collections, Corie enjoys collecting non-western art, admiring nature, and taking too many pictures of her cat.