There’s Never Been an Actor Like Buffalo Bill – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine in Summer 1999

There’s Never Been an Actor Like Buffalo Bill

By Gordon Wickstrom, Guest Author

In the annals of theatre, in the long history of actors land acting, Buffalo Bill as actor stands alone. Throughout more than a decade on stage, he played only himself, in plays exclusively about himself—extravagant fables of his prairie adventures as the greatest of the scouts. His career at this time was a steady rhythm of long winters as an actor-manager in the nation’s theatres followed by summers in the field where he continued to compose the high drama of his life. There has been no other actor like him.

In 1872, following the Royal Buffalo Hunt in Nebraska, 25-year-old Buffalo Bill Cody was lured to New York where he found himself in full dress in the Bowery Theatre watching a professional actor portraying Buffalo Bill in the border drama titled “Buffalo Bill: King of the Border Men.” He was both embarrassed and enthralled.

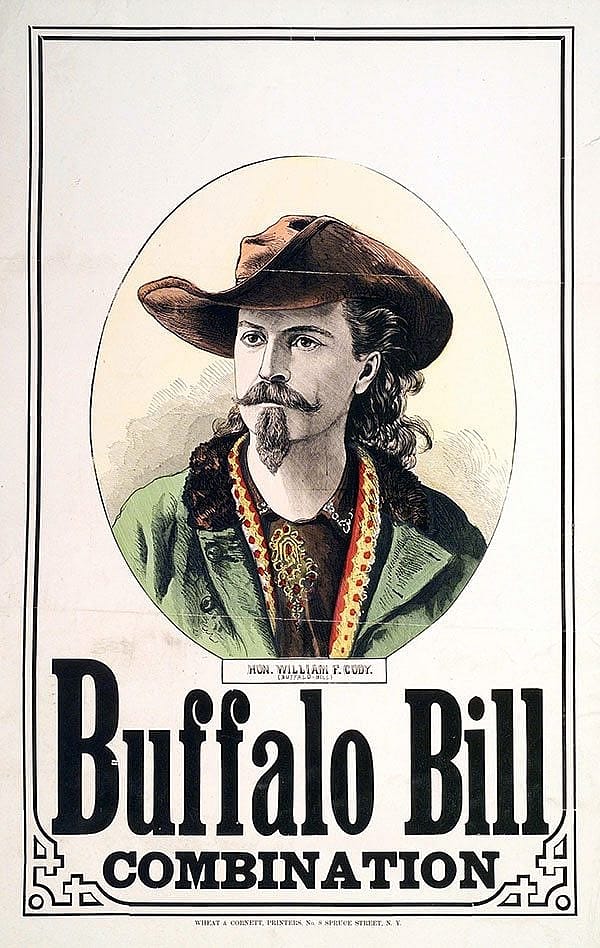

Those who had brought him to New York, thinking they might “develop” the young hero, suggested to Cody that he should perform Buffalo Bill himself, in plays about what the public believed to be his adventures out West. They would pull in the notorious Ned Buntline as playwright.

Tempted by the prospects of big money, Cody agreed and, with Texas Jack Omohundro and the accomplished Italian danseuse Giuseppina Morlacchi, set out to play Ned Buntline’s execrable “The Scouts of the Prairie,” opening in Chicago on December 18, 1872.

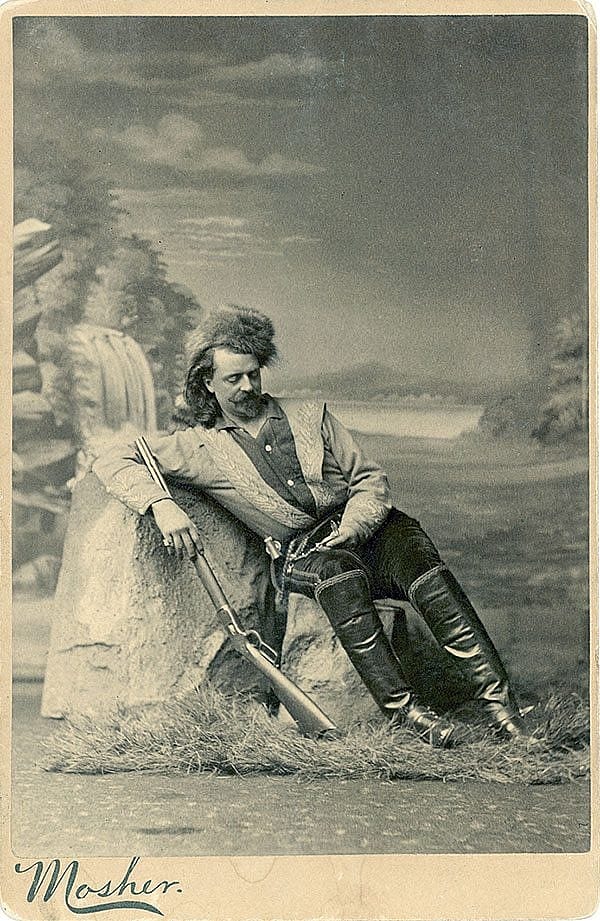

The performance was terrible, and the play itself was even worse. Still, the press noted that the public was wild about Buffalo Bill. And so, while his border dramas only slowly developed dramatic credibility, the presence of Cody as Buffalo Bill enchanted and excited audiences everywhere. He was the real thing – an icon of the audiences’ very idea of the West. He was tall and handsome, charismatic, yet appealingly modest and good-humored. He was debonair in the ancient chivalric way.

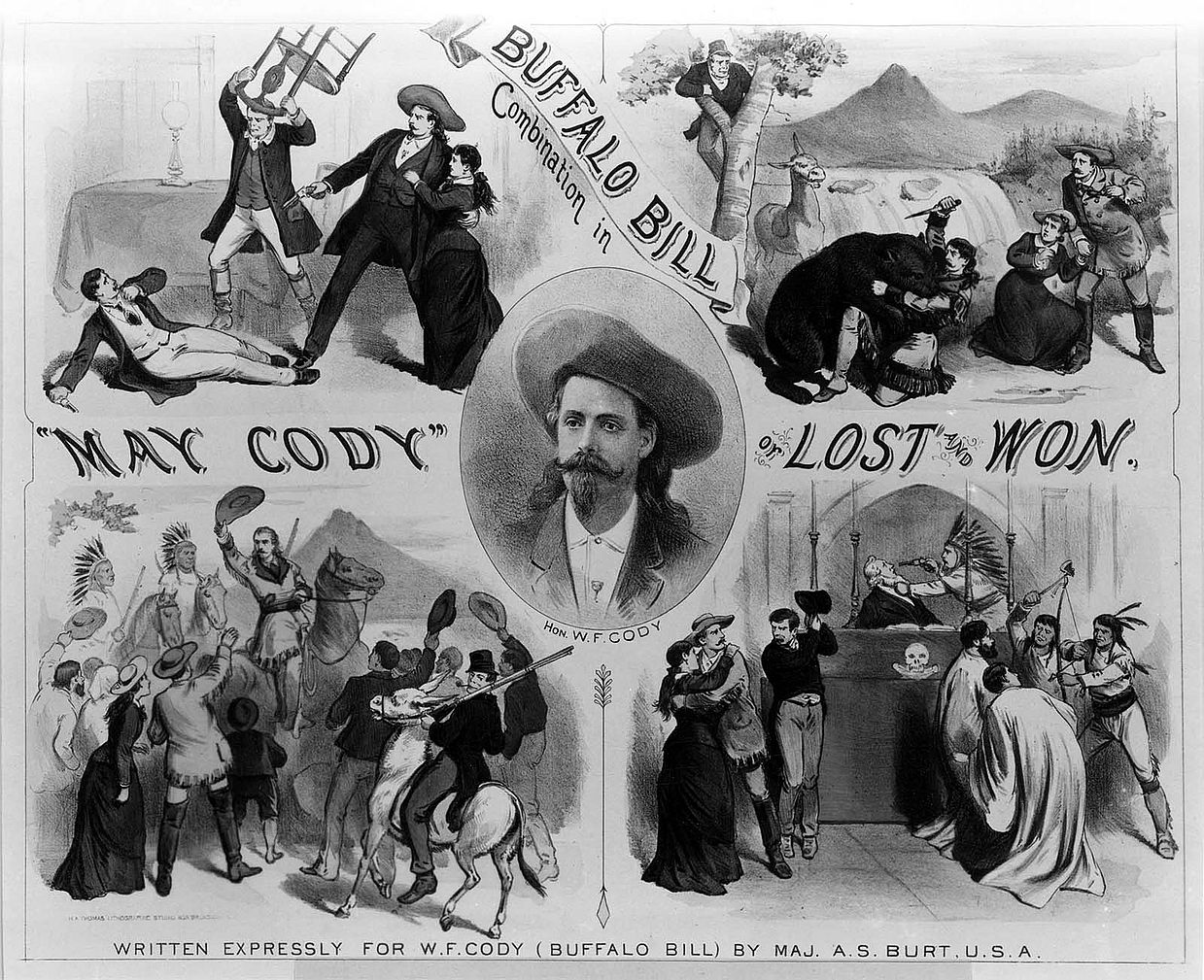

That first season with Buntline was a financial disappointment, tempting Cody to give up the stage. Instead, he formed his own “combination,” adding Wild Bill Hickok, his early friend and benefactor. Hickok caused such chaos on stage that he stayed only a single season.

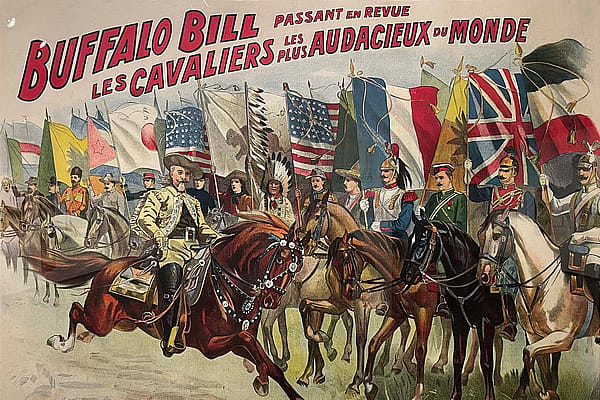

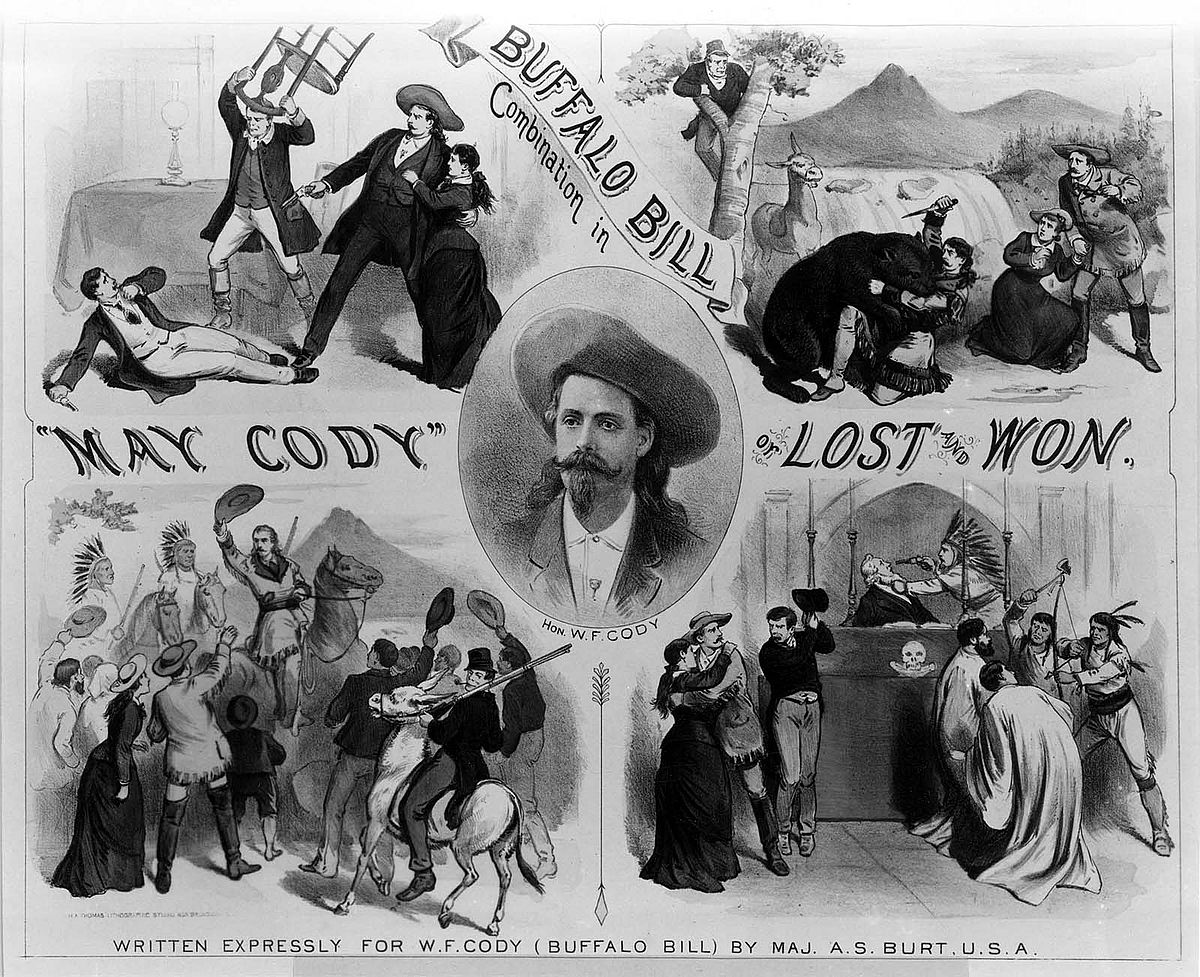

Cody never looked back. That second season saw the star of the young actor rise steadily both in the adulation of audiences and box office returns. His combination of players traveled the country, performing a new play each season. Eventually he would perform in 14 plays during his stage career. As these melodramas about his reputed adventures increased slowly in credibility and polish, Cody himself became an accomplished and sensationally popular performer. He, of course, always took the “Buffalo Bill” role, while managing every detail of his company.

This pattern of spending winters on stage and summers in the field reinventing himself lasted until 1886, overlapping by a bit the advent of his Wild West exhibition. His last appearance on the legitimate stage was in Denver in 1886, in “The Prairie Waif.”

The events of centennial year 1876 are most fully illustrative of Cody’s career as an actor. That year his spring tour was interrupted by the sudden death of his only son, Kit Carson Cody, in Rochester, New York. In response to a telegram from his wife, Louisa, Cody rushed from a Chicago stage to the boy’s bedside on April 20, only a few hours before the child died. That night, according to Louisa, Cody’s acting career seemed to him especially empty, even a mockery. Perhaps he would give it all up. But there was something else….

George Armstrong Custer, as part of the Big Horn and Yellowstone Campaign of the Seventh Cavalry, was marching westward toward the Little Bighorn to intercept the Sioux and Cheyenne under Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse and to end, once and for all, the Indian troubles. The campaign would need the best scouts, and Cody got the call to duty in Rochester almost on the day of his son’s death. In something like relief from the intensity of his grief, he prepared once again to go West – to be part of this fateful expedition.

Custer was well on the way to his disaster by the time Cody could arrange to close down his acting company and join the Fifth Cavalry at Fort Laramie under the command of Eugene A. Carr.

Twenty-two days after Custer’s annihilation, Cody found himself involved in an incident that would become the most discussed of his career. In the northwest corner of Nebraska, on War Bonnet Creek, Cody, in single combat, killed Yellow Hair (Yellow Hand), a minor Cheyenne chief.

Cody had known that an engagement with Indians could be expected and that the entire campaign was being covered in detail by the nation’s press; in fact, the eyes of the nation were fixed on the high plains of the Sioux and Cheyenne—and the U.S. Cavalry. So, on that special morning of July 17, 1876, facing the Cheyenne, Cody arrayed himself in a stage costume, that of a Mexican vaquero, all black velvet, slashed with scarlet, with silver buttons and lace. In this habit he rode out against the Cheyenne Yellow Hair, shot Yellow Hair’s horse from beneath him, and shot the chief himself through the leg. With both men on the ground, each fired at the other. Yellow Hair missed. Cody did not. As he told it, “He (Yellow Hair) reeled and fell, but before he had fairly touched the ground I was upon him, knife in hand, and had driven the keen-edged weapon to its hilt in his heart. Jerking his war bonnet off, I scientifically scalped him in about five seconds.”

Riding by in pursuit of the Cheyenne, the men of the cavalry gave Cody a rousing cheer acknowledging the greatest of the scouts. It was the Grand Theatre of the Plains.

Much about the incident reveals Cody’s sense of the theatrical and its values. The costume he wore was just that: a costume. There was the unmistakable mark of “performance” about all of it, not the least the soldier audience that viewed it. That the event was indeed high in performance values is certified by Cody’s late-in-life effort to make a moving picture documentary recreation of that day’s events.

It is not too much to say that all of Cody’s life may be thought of as movement among the varied but related theatrical venues: the High Plains on which he “performed” his life in a more or less conscious, even deliberate way, the more formal expression of the stage itself, the great outdoor arenas of the Wild West exhibitions, and finally his “staging” of an entirely new social/economic community to Wyoming’s Big Horn Basin through water and agricultural development—all with himself as star and impresario.

But it is the killing of Yellow Hair (Yellow Hand) in that epic summer of 1876 that serves as a model for the singularity of Cody’s career as actor. On August 22 of that year, after the engagement in which Yellow Hair died, Cody took his discharge as chief of scouts and returned East, explaining, “There being but little prospect of any more fighting, I determined to go East as soon as possible to organize a new ‘Dramatic Combination’ and have a new drama written for me, based on the Sioux war. This I knew would be a paying investment, as the Sioux campaign had excited considerable interest.”

The resulting border drama, “The Red Right Hand; or Buffalo Bill’s First Scalp for Custer” was, as in Cody’s words, “A five-act play, without head or tail, and it made no difference at which act we commenced the performance… It afforded us, however, ample opportunity to give a noisy, rattling, gunpowder entertainment, and to present a succession of scenes in the late Indian war….”

It was during these years on stage that Cody found the immense authority that he came to have in American life. Here he established his defining voice in the development of the West of which he dreamed so greatly. His imagination of the West, in both art and life, in substantial ways remains our own today.

This season of 1876-77 epitomizes the career of this unique actor – and the burden of this essay – who for a sustained stage career played only himself in dramas exclusively about himself based more less on materials of historical and cultural import that he was instrumental in generating on the scene of the national westward expansion.

About the author

Gordon Wickstrom is an emeritus professor of drama retired to his home town of Boulder, Colorado, where he writes about angling and directs the plays of Shakespeare. A more complete treatment of the subject of Buffalo Bill as actor can be had in Wickstrom’s essay in Journal of the West, Vol. 34 (January, 1995).

Post 122

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.