A Seasonal Look at Buffalo Bill – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine in Winter 2002

A Seasonal Look at Buffalo Bill

By Juti A. Winchester

Former Curator, Buffalo Bill Museum

Historians have spent much time and paper documenting everything one could think of concerning Buffalo Bill, generally segmenting his life chronologically according to his activities. For example, a scholar might look at Cody’s stage career from 1872 to 1885, or they could examine his involvement with the town of Cody, Wyoming, from 1894 to his death in 1917. However, studying his life work from a seasonal perspective offers another view of William F. Cody. The Colonel’s summer exploits are his most well-known and often told. By looking at the period of time between Cody’s birthday (February 26) and the first of June, we can see what “spring” meant in Buffalo Bill’s world.

Cody’s life was filled with a whirl of activity beginning with his childhood. March of 1857 found him without a father and before summer, Russell and Majors employed him as a messenger, making it possible for him to gain later fame as a relay rider for the Pony Express. In late February 1864 Cody, like many young men of his generation, enlisted in the army on the Union side in the Civil War.

A number of other life-altering events occurred in Cody’s life in springtime. On March 6, 1866, he married Louisa Frederici, embarking on a life-long but rocky union with her. In the spring of 1972 Cody traveled East and in New York was induced to step on the stage for the first time, albeit briefly, immediately fleeing the footlights and the notoriety. He was later lured back by his friend John B. “Texas Jack” Omohundro and subsequent springs found him on the road to everlasting fame with the “Buffalo Bill Combination.” In April 1876 the Codys’ only son Kit Carson died, a sorrowful loss that Buffalo Bill later said he never really got over.

Many of us have visions of budding plants, newborn animals, and other images of new life and regeneration when we think of “spring.” For farmers, ranchers and others whose livelihood depends on the seasons, spring means a new round of work in order to ensure the year’s production. Buffalo Bill faced the same situation with his seasonally produced show, as work for the next year had to be commenced almost before the past year was truly finished.

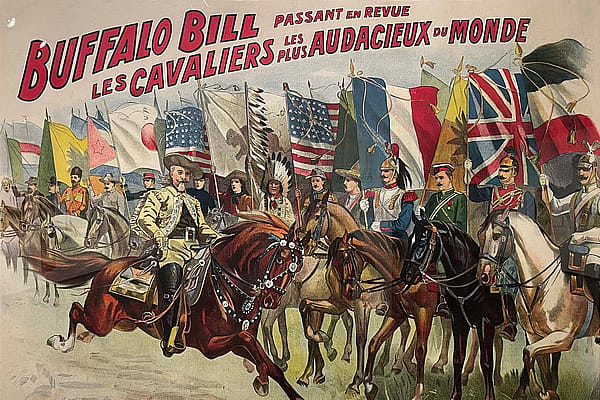

Study of the stacks of correspondence in the McCracken Library’s collection of Buffalo Bill material reveals an interesting pattern: although he was a prolific summer, autumn, and winter correspondent, Cody didn’t seem to write many letters between about the middle of January and the middle of May. Looking at the routes and schedules compiled by library staff, we find that for over thirty years, from sometime in April to around the middle of November, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West (or some form of his exhibition) was on the road.

Letter-writing was Cody’s only means of keeping up with activities among his extended family as well as his business associates while he was traveling with the Wild West. While the show went into winter quarters in the East, Buffalo Bill sped West to his ranch at North Platte, Nebraska and later to Cody, Wyoming, to rest however he could and to see his family.

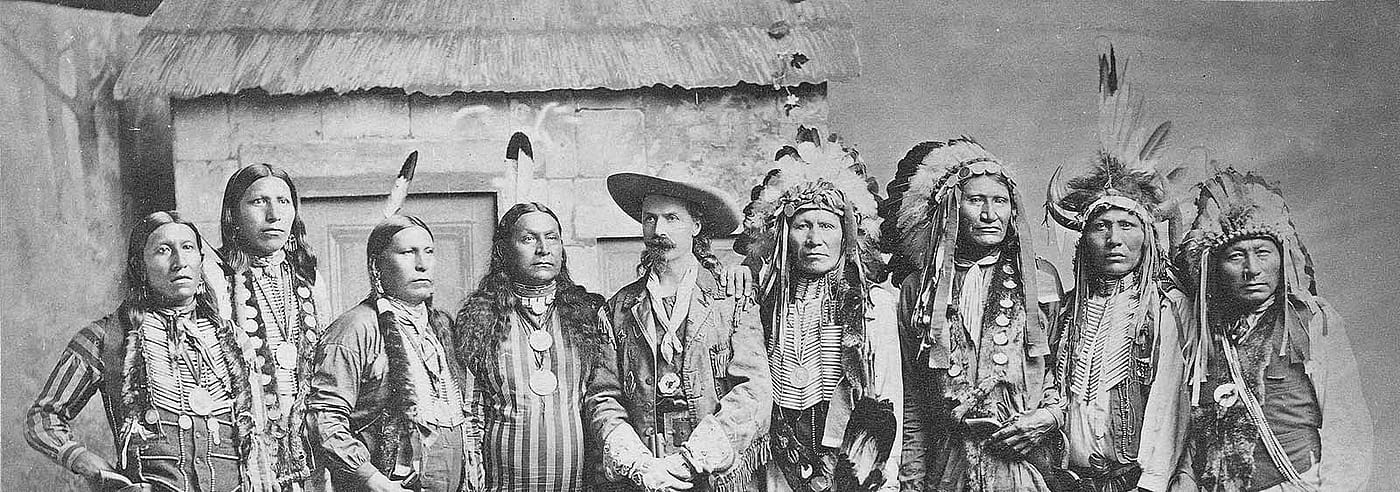

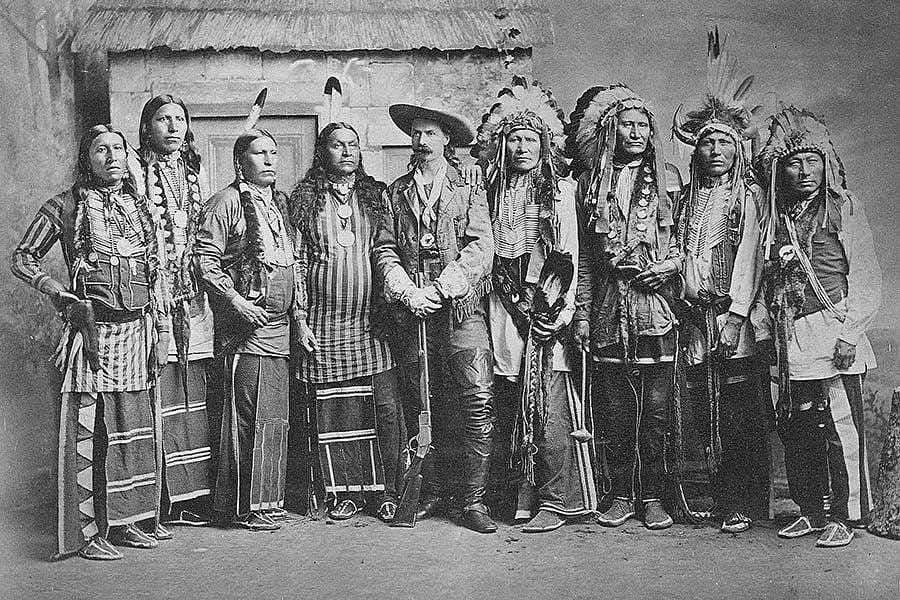

When the winter holidays were over, Cody again crisscrossed the nation checking on his business interests, visiting potential investors, organizing the show route, and recruiting talent for the Wild West. By the end of February, he had returned to the East and was deep in preparation for the next show season. Thus, in the springtime Cody was able to conduct his business face-to-face, making paper correspondence unnecessary.

An April 5, 1912, letter to Clarence Rowley written from Scout’s Rest Ranch shows how busy the Colonel’s time off could be. Cody scribbled, “I arrived here this morning in fine health. But very tired. Had so much to do at Cody in a snow storm and so short a time to do it in. Besides my own business I had so much to do for the town which they expect me to do. As I am heavly interrested there. And being the father of the town. When I am there they expect me to lead.”

Cody goes on to relate plans to “go over” the North Platte ranch with his son-in-law, speak at the Commercial Club in Omaha, go to Trenton, New Jersey, to work with the wintered show, and meet other mine investors in New York City, all within a week of the letter. He finishes, “Ex. Haste. A lot of town people just drove out to see me. More talk & I am tired with a big bunch of mail as yet unopened.”(1) Incidentally, opening day for the 1912 show was scheduled for April 20.

After the Wild West was bankrupted in Denver in summer 1913, the old scout began to have a little more time to himself—a very little. Later that same year, Buffalo Bill was able to accompany the Prince of Monaco on what later turned out to be a famous and successful hunt, something he wouldn’t have been able to do had business been as usual with the Wild West. Spring 1914 and 1915 found Cody again busily rehearsing, this time with the Sells-Floto Circus, but his workload was lighter because he no longer had to organize the show or supervise employees. In March 1916 he was busy again, writing his biography for Hearst magazine while staying with his nephew in New Rochelle, New York.(2)

Cody spent the some of the last spring of his life in the East with family and at the scene of some of his earlier triumphs. By the end of April 1916, however, Buffalo Bill was on the road again, bringing the West to audiences far from the wild places he loved. He had big plans for the spring of 1917. Cody hoped to get his own Wild West off the ground and running again in order to restore his fortune and reassume command of his future, but his health failed him before winter released its grip on the West.

Notes:

- Letter from William F. Cody to Clarence W. Rowley, April 5, 1912, MS6 Series I:B Box 2, f 17, McCracken Research Library, Buffalo Bill Center of the West.

- Nellie Snyder Yost, Buffalo Bill: His Family, Friends, Fame, Failures, and Fortunes (Chicago: The Swallow Press, 1979), 397.

Post 128

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.