Buffalo Bill, Friend of the American Child – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine in Summer 2015

Buffalo Bill, Friend of the American Child

By Martin Woodside

It’s no secret that William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody was a hero to generations of American children. Cody’s reputation as an affable father figure grew rapidly in his later years—notably from the turn of the twentieth century until his death in 1917—as he was increasingly lauded in the press as a friend to the American boy and, in fact, children of all ages. Boy Scouts of America President Dan Beard touted Buffalo Bill as an inspiration for the Scouts and described him as “the one man whom all boys love.”

When Cody died, newspapers featured images of inconsolable children, mourning the death of their hero, and after Cody’s funeral, every grade school child in Denver received a flower from the offerings. While Buffalo Bill remained a fixture in the culture of American childhood throughout his career as an entertainer, his ascension to this almost saintly status was hardly accidental. Indeed, Buffalo Bill’s transition to silver-haired grandfather and benefactor of the American child was closely tied to the success of his show business career, and he and his partner worked hard to facilitate this transition.

A leap from page to stage

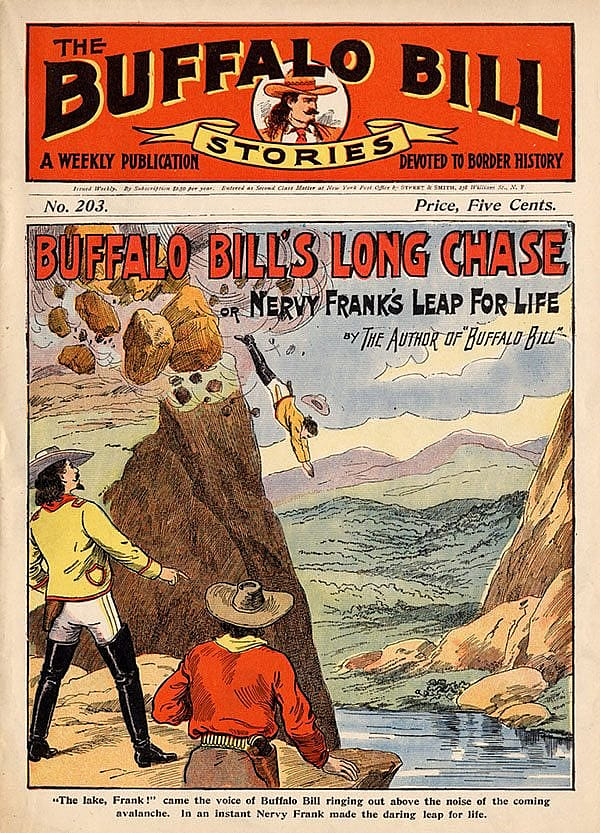

Immortalized in Ned Buntline’s 1869 work, Buffalo Bill: the King of Bordermen, Cody first gained fame as a dime novel hero. By 1872, he was playing himself on stage, engaged in a theater career that would span thirteen years. Forming the Buffalo Bill Combination, Cody packed playhouses throughout America, winning over large crowds—if not always local theatre critics—with action-packed fare such as Scouts of the Plains, or Red Devilry As It Is; or Red Right Hand, or Buffalo’s Bill’s First Scalp for Custer. These plays saw Cody trafficking in the same blood and thunder storylines that populated Buffalo Bill’s dime novel adventures, much to the delight of boys who voraciously consumed these yellow-backed novels. Massing to see their hero on stage, these raucous young fans became known as the gallery gods and represented a substantial part of Cody’s audience.

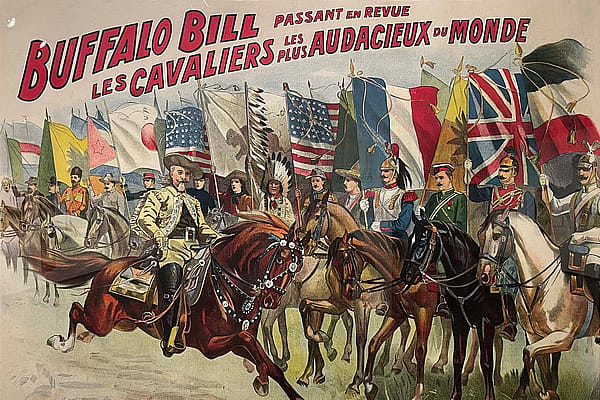

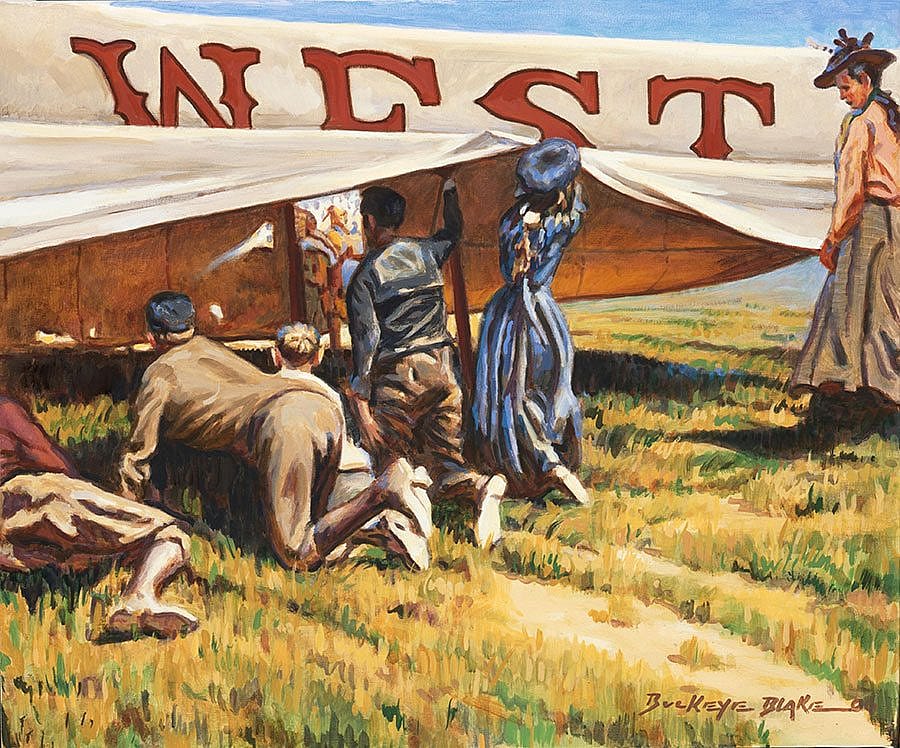

When Cody transitioned from stage to open arena in 1883 (the first being The Wild West: Buffalo Bill and Dr. Carver Rocky Mountain and Prairie Exhibition), the gallery gods eagerly followed him. Right from the start, young fans made up a substantial part of the audience for Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, and Cody and his partners were happy to have them. Many of the reviews for early runs of the Wild West mirrored reactions to Cody’s stage show. Some critics described the thrill of seeing blood and thunder action brought to life before their eyes, with sham Indian battles and live gunplay mixed gleefully together. Others were less thrilled, claiming the show lacked morality and played to the basest elements in the crowd. These critics perceived younger fans as particularly vulnerable.

Blood and thunder tales: too much for the kids?

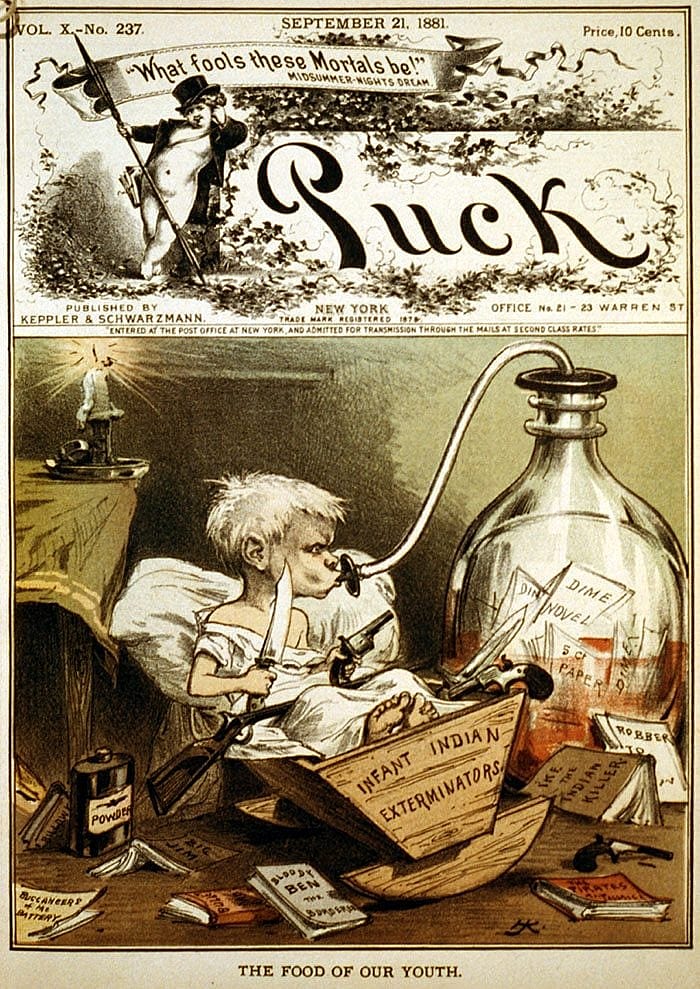

In fact, these fears grew directly from adult concerns about dime novels. This emerging genre caused something of a moral panic in the second half of the nineteenth century as many parents and guardians raised grave concerns about the dangers of children reading sensational literature. Cultural critics wrote long diatribes against the evils of dime novels, especially the violent adventure stories they christened “blood and thunder” tales.

Louisa May Alcott famously devoted a chapter of her novel Eight Cousins to the damaging effects of these stories. Focusing on books that targeted boys, (Alcott herself had written sensational romances under the pen name A.M. Barnard.) she lambastes dime novels for their unrealistic story lines and irresponsible characters. Moral crusader Anthony Comstock went a step further, describing the literature as tools of Satan in Traps for the Young, his 1883 polemic against cheap reading. An extremist to some, Comstock became a special agent for the U.S. Post Office and successfully pushed for and passed federal legislation that banned the mailing of obscene literature.

Buffalo Bill was certainly no stranger to blood and thunder novels. According to Cody biographer Don Russell, Buffalo Bill figured in more than two hundred dime novels—more than any character other than Jesse James. Recalling the early planning of the Wild West, Cody’s main partner, Nate Salsbury, describes Buffalo Bill as the perfect front man precisely because dime novels had already established him as a household name among the nation’s children. Still, Buffalo Bill’s status as a dime novel hero came under more careful scrutiny throughout the 1880s as the Wild West and Buffalo Bill became increasingly popular. During those years, Cody and his partners had to manage Buffalo Bill’s image and his relationship to his child audience very carefully.

Following a hero isn’t always easy

The Wild West drew on many of the same themes as the typical dime western, featuring high-octane battles with road agents and Indians. By mimicking dime novel theatrics too closely, Cody left himself open to the same kinds of attack that sensational literature endured, including charges of corrupting the minds of impressionable young boys. Certain critics had long accused Buffalo Bill’s Combination of drawing the wrong crowd and promoting dime novel heroics.

As the Wild West grew more popular, these charges took on more weight. Newspapers were quick to report stories of boys who’d been injured and even killed while “playing Buffalo Bill.” More common, though, were stories of children, mostly boys, who’d left home to head West and follow in their hero’s footsteps. This 1883 Philadelphia Inquirer story is typical in its concerns:

William Dickinson, aged fourteen years, and William Stevenson, aged eleven, are missing since Monday, since which time nothing has been seen or heard of them. They both left home dressed with the intention of seeing Buffalo Bill. They had been in the habit of reading exciting stories such as Indian tales, etc., and it is supposed that they must have left with Buffalo Bill during Monday night. The mothers of the young lads are greatly worried, and if the boys do not return soon their minds might become deranged.

Buffalo Bill’s seductive appeal to impressionable youth even stretched beyond national boundaries. During the Wild West’s first trip to England in 1887, British papers described a “special staff of detectives” that had been stationed at the Liverpool docks to prevent runaways from stowing away with Cody’s show.

Cody and his partners actively sought publicity that countered these stories. In fact, the Wild West’s 1884 program reminds the audience that women and children could attend the show “with Perfect Safety and Comfort, as arrangements will be made with that object in view.” Similar disclaimers appeared regularly in the Wild West’s promotional materials.

What was a Wild West performance to do?

At the same time, there was only so much Cody and his partners could do to counter Buffalo Bill’s image as a dime novel hero—and only so much they wanted to do. In truth, this image was central to Cody’s appeal as a showman, especially to his younger audience members. Instead, as the Wild West increasingly became a form of mass entertainment, geared to attract audience members of all types and all ages, Cody and his partners sought to balance Buffalo Bill’s appeal as a dime novel hero with his role as an educator. Consequently, his Wild West balanced themes of frontier adventure with claims of the show’s educational value throughout the run of Buffalo Bill’s extravaganza.

From the start, programs and promotional materials billed the Wild West as both entertaining and instructive. By 1885, though, the program extolled the Wild West’s educational value more. A new description of Cody appeared under the sub-heading “As an Educator,” with journalist Brick Pomeroy writing, “I wish there were more progressive educators like Wm. Cody in this world.”

The “As An Educator” section had grown to four paragraphs by 1887—half a page in length. In it, Pomeroy extolls Cody as a staunch patriot who “wishes to present as many facts as possible to the public, so that those who will, can see actual pictures of life in the West, brought to the East for the inspection and education of the public.” Cody—who never referred to the Wild West as a show—and his partners, especially publicist John Burke, took an active role in promoting the Wild West as a realistic presentation of frontier life, one with vast educational value. The programs proudly declared the Wild West to be “a colossal Object School of living lessons,” with Pomeroy going so far as to claim the show could be called, “the Wild West Reality.” These efforts did much to shape public perception of the Wild West. By the early 1890s, citizens increasingly perceived the show as respectable entertainment, and Cody, himself, a benefactor and de-facto father figure for American youth.

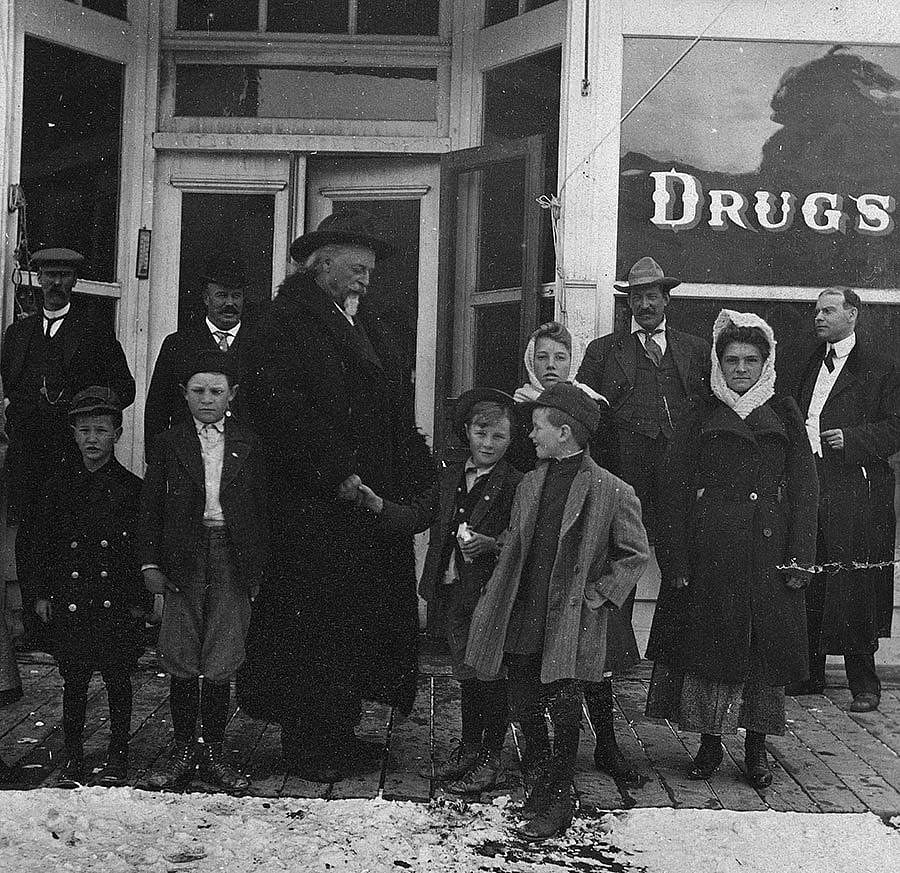

Cody and company treated 6,000 children to a free performance

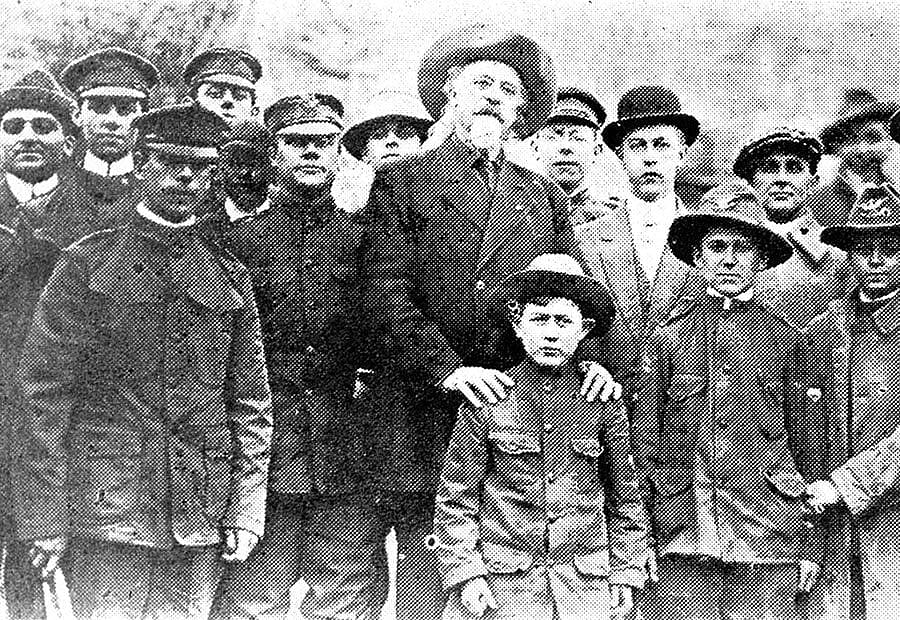

In 1893, the planners of the World’s Columbian Exposition, also known as the Chicago World’s Fair, refused to include the Wild West, a decision they likely regretted later. Cody and his partners set up on the Midway, just outside the fair’s gates. Throughout the run of the fair, they played to immense crowds and won rave reviews from the press. This long stand in Chicago also served to put an exclamation point on the changing relationship between Buffalo Bill and his child audience. After the fair’s organizers decided against granting the city’s poor children admission for a day, Cody and company treated 6,000 children to a free performance of the Wild West. The press celebrated his goodwill, while the boys themselves presented Buffalo Bill with a solid gold plate in the shape of a messenger card, acknowledging Cody’s great service to the “Chicago Waifs Mission Messenger,” and signed by the “Waifs of Chicago.”

Newspaper stories had anxiously described the massing numbers of newsboys and bootblacks attracted by Buffalo Bill’s Wild West a mere ten years earlier. By 1893, though, that crowd remained a mainstay of the Wild West audience, but the public perceived the relationship between Cody and these young audience members much differently. Now, Buffalo Bill played the role of father figure, a benefactor, and friend of these poor boys.

As a dime novel hero, Buffalo Bill risked being read as a threat, seducing young boys to run away from home, only to lead lives of destitution or depravity. The Wild West, however, successfully cast him in a different light. By 1893, papers were less likely to run cautionary tales about runaway boys than to run articles like the N.Y. America and Mercury‘s “Cured of Cowboy Fever.” This short piece recounts a happy father who visits Buffalo Bill to hand in his son’s collection of ropes, wooden daggers, old feathers, and toy pistols. Apparently, having seen Buffalo Bill in action, the boy had learned the truth about frontier life and had no more need for foolish play.

As his fame grew, Cody seemed to become increasingly fond of his young audience members and grew gracefully into the role of benefactor to the nation’s children. He frequently admitted poor children to Wild West performances free of charge and paid numerous visits to schools and hospitals. In his later years, Cody did develop a close relationship with the Boy Scouts and became a vocal proponent of the organization’s values, urging children to spend more time outdoors while learning skills such as shooting and riding. Indeed, when he died in 1917, Buffalo Bill clearly was the friend of the American child—a reputation that Cody worked hard to earn.

About the author

Dr. Martin Woodside earned his PhD in Childhood Studies from Rutgers University-Camden, New Jersey. In 2013–2014, he was a fellow at the Buffalo Bill Center at the West, researching his dissertation, Growing West: American Boyhood and the Frontier Narrative. Buffalo Bill became a major focal point for the project, a cultural history, exploring the dynamic interaction of boyhood and frontier mythology in America during the second half of the nineteenth century.

Click here to read “The Cowboy Scourge.”

Post 145

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.