The Great Equestrian Statue Race – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine in Spring 2007

The Great Equestrian Statue Race: Theodore Roosevelt and the Efforts to Memorialize Buffalo Bill

By Jeremy Johnston

Ernest J. Goppert Curator of the Buffalo Bill Museum

Ed. note: As we celebrate our Centennial in 2017, we share this article from ten years ago that recounts how the community of Cody won the race to memorialize William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody in sculpture.

For many years, it was assumed that immediately following the death of William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody in 1917, the great battle over his final resting place began. However, Cody, Wyoming, and Denver, Colorado, did not immediately fight over the location of Buffalo Bill’s gravesite. Wyoming held some resentment that Buffalo Bill’s body would remain in Denver, but they accepted the loss of the gravesite as inevitable. The Park County Enterprise, Cody’s hometown newspaper, surprisingly spoke highly of the Colorado location: “Internment will be on beautiful Lookout mountain [sic] which overlooks the city.”

Residents of Cody gave up on becoming the site of Buffalo Bill’s grave and decided instead to be the first to erect an equestrian statue as a memorial to their city’s founder. They soon found themselves in competition with Denver’s effort to memorialize Buffalo Bill by also erecting an equestrian statue—this one near the gravesite. Thus began a race of sorts between Cody and Denver to complete a suitable memorial honoring the memory of Buffalo Bill, with Theodore Roosevelt assisting—and deterring—both communities’ efforts.

On January 14, 1917, Denver hosted Buffalo Bill’s funeral with John W. Springer delivering the eulogy. Springer noted, “It is fitting that his tomb should be hewn out of the eternal granite of the Rockies, and it is to be hoped that a magnificent equestrian statue shall be erected by the people of the great West….” Springer, a man of significant wealth and at one time a leading Republican of Colorado, now found himself on the public stage after a long silence that followed a sensational scandal.

A close friend of Roosevelt, Springer formed the Roosevelt Club to support Roosevelt’s 1904 presidential campaign and nearly became his vice-presidential candidate. Springer also focused on local politics and ran unsuccessfully for mayor of Denver. Despite this political loss, Springer remained one of the foremost political and social leaders of the Denver community until an infamous scandal interrupted his political career.

It seems Springer’s second wife, Isabel, was secretly involved in a love affair with a former lover, Tom von Phul. When von Phul blackmailed Isabel with their love letters, one of Springer’s business associates and close friends, Frank Henwood, shot and killed von Phul in the bar at the Brown Palace Hotel in Denver. Henwood also managed to kill an innocent bystander and severely wound another bar patron.

When the newspapers learned of the reason behind the killings, Isabel and John Springer’s troubled relationship made headlines across the nation. Springer quickly divorced his wife and withdrew from an active public life. Delivering the eulogy at Buffalo Bill’s funeral brought Springer back into the center of attention. Using his newfound fame as Buffalo Bill’s friend, Springer organized the Col. W.F. Cody Memorial Association (CMA) to erect an equestrian statue on Lookout Mountain.

Meanwhile, on the same day the official funeral occurred in Denver, efforts to memorialize Buffalo Bill in the town of Cody began with a memorial service hosted by the Society of Big Horn Pioneer and Historical Association. The organization’s secretary, William Simpson, sent out letters requesting members gather at the Irma Hotel and then march to the Temple Theater for the memorial service. In the days leading up to the memorial service, members of the association, possibly still stewing over losing the burial location for the Great Scout, likely discussed ways to honor their town’s namesake.

On the very day residents of Cody met for Buffalo Bill’s memorial service, L.L. Newton sent a telegram to Theodore Roosevelt and other notable personages on behalf of the newly formed Buffalo Bill Memorial Association (BBMA). His hope was that Roosevelt and the other notables would lend their support to the BBMA, thereby generating publicity for the group. The membership of this new organization, led by William Simpson’s wife Margaret, included prominent Cody citizens Charles Hayden, W.T. Hogg, Sam Parks, and L.L. Newton. The Park County Enterprise reported on the BBMA’s efforts:

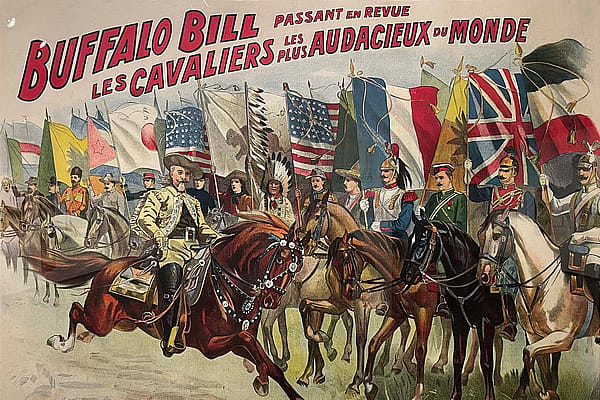

It is proposed to erect a monster memorial to the colonel which will cost anywhere from $25,000 to $50,000, and negotiations are already under way toward the selection of some noted sculptor in order to get a model. It is also proposed to follow the lines of the famous Rosa Bonheur picture as closely as possible. [To raise funds, the new association ordered] several thousand beautifully colored posters of the colonel, which will be given to those who make a donation of any kind for the statue. It is proposed that all the school children of the United States send Buffalo nickels for the fund.

The BBMA’s efforts soon met a significant setback when Roosevelt declined to participate. In a letter to Newton dated January 18, 1917, Roosevelt wrote, “I sincerely regret that it is not in my power to take part in the movement you propose. If I could join any new societies for any purpose whatsoever at the present time, I would join this one, but it simply is not possible.” He did, however, indicate his support for the project. “Buffalo Bill was one of the great scouts in the Indian wars that opened the West. He typified, as emphatically as Kit Carson himself, one of the peculiarly American phases of our western development and most certainly should have a monument.”

Despite Roosevelt’s protestations, he soon found himself as an honorary vice-president for Denver’s CMA led by his friend, John Springer. On February 5, 1917, Roosevelt received a telegram from Springer requesting an audience for Sam Dutton, vice-president of the association; Buffalo Bill’s adopted son, Johnny Baker; and former Wild West show manager, Louis Cooke. Springer noted the proposed meeting with Baker and Cooke “pertains [to] proposed memorial to Colonel Cody.” Roosevelt replied, “Of course I will give the audience you request, but it is impossible to make any speeches at present. Will gladly write letter for Colonel Cody Memorial [sic].”

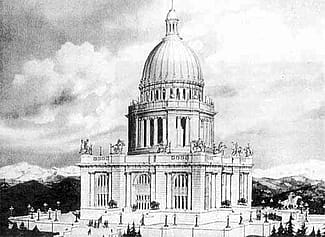

Shortly before the meeting, the New York Times ran an article announcing Roosevelt’s acceptance of the vice-presidency for the CMA. The article quoted Roosevelt’s praise of Buffalo Bill, “whom he described as ‘the most renowned of those men, steel hewed and iron nerved, whose daring opened the West to settlement and civilization.'” The Times article described the proposed memorial:

Denver has donated a plot for the monument on Lookout Mountain and has offered to become the custodian of the memorial. The peak chosen for the memorial is to be renamed Mount Cody and on it will be erected a mausoleum, the interior of which will contain the tomb, as well as the trappings, relics, paintings, personal souvenirs, gifts, and collections of Buffalo Bill. Sculptured groups illustrating episodes in the life of the frontier will flank each corner of the monument. There will also be a heroic equestrian statue of the Scout as he looked in youth.

With Roosevelt joining Denver’s association, it appeared the residents of Cody had lost their chance to erect a memorial. Clearly, Denver had more resources for their fundraising ventures, starting with its population. In 1910, Denver’s population stood at 213,381 and by 1920, it had grown to 256,491, ranking it as the twenty-fifth largest city in the United States. The city of Cody’s 1910 population stood at 1,132, growing to 1,242 by 1920.

Roosevelt assisted the Denver organization with their plans to erect an equestrian statue by collecting funds and suggesting potential artists. In a letter to Springer dated March 8, 1917, Roosevelt recommended Alexander Phimister Proctor be the artist for the Buffalo Bill equestrian statue. Springer wrote back to Roosevelt noting the association agreed with Roosevelt’s choice.

On April 2, 1917, Woodrow Wilson called for a declaration of war against Germany, and her allies and the demands of the Great War quickly overshadowed efforts to erect a Buffalo Bill memorial. Despite this, Albert Mayfield, the secretary of the CMA, remained optimistic. He reported to Roosevelt, “Contributions are coming in very satisfactory, considering the ‘war times,’ and with the concerted aid of Col. Cody’s admirers, we will be able to raise a large and sufficient fund with which to erect a magnificent PIONEER monument to his memory, and to the memory of other frontiersmen who helped blaze the trail.”

Roosevelt continued to collect funds after the declaration of war, including $100 from English author, B. Cuninghame Graham. Graham wrote Roosevelt:

I saw by chance today in Harper’s Magazine that a national monument is to be raised to my old friend Colonel Cody; that it is to take the form of a statue of himself on horseback (I hope the horse will be old Buckskin Joe), that he is to be looking over the North Platte…. If in another world there is any riding—and God forbid that I should go to any heaven in which there are no horses—I cannot think that there will be a soft swishing as of the footsteps of some invisible horse heard occasionally on the familiar trails over which the equestrian statue is to look.

By the end of April, the Colorado newspapers reported the Cody Memorial fund had raised $6,630.72 despite the entry of the United States into World War I. The cost of the project, however, would be over $200,000.

On April 17, 1917, Springer’s scandalous ex-wife passed away in New York and once again Springer’s connection to the infamous murder reappeared in print. The Park County Enterprise also reported the death, but it is unclear if this was an attempt to discredit the CMA or simply to inform Cody residents who were certainly familiar with the past scandal. Despite the war and his personal life again making the headlines, Springer still remained optimistic about the memorial. Springer wrote to Roosevelt thanking him for his services, but now Springer seemed more consumed with the building of the mausoleum.

“Within a few days we will have a pen sketch of the proposed memorial temple…and it will be a magnificent structure,” proclaimed Springer. “The equestrian monument which Mr. Proctor has in mind will form part of the temple.” Enclosed in the letter was a brochure with the proclamation, “In times of war the Nation’s people should remember those who gave their services in the past.” The brochure described plans for a “great mausoleum” containing Cody’s relics adorned with an equestrian statue and surrounded by a park complete with live buffalo. Springer declared, “This is going to be the greatest thing of its kind ever erected in the world and if the proper call can be made through the influential channels, I am sure that the response would be spontaneous and overwhelming.”

In September 1917, Springer reported to Roosevelt that the group now wanted to raise $1 million for the project instead of the $200,000 as originally planned. The letter also introduced Mr. A.S. Hill who “will show you some beautiful work we are now getting out; we expect to send it to the confines of this country and we expect to raise the money within a year and to start at once the first unit.” Roosevelt did not record his feelings regarding the increased cost. However, when Springer later attempted to arrange a face-to-face meeting with Roosevelt in Kansas City to discuss “personal business,” Roosevelt declined. Clearly something was amiss—probably Roosevelt had privately indicated his disproval of attempting to raise $1 million during a time of America’s involvement in a world conflict.

Springer and the CMA began to worry about the future success of the more-costly project. In October 1917, the CMA began raising funds in Cody from an office located within the Irma Hotel. To raise money, the association distributed a school play called “Civilization’s Course in America,” which local schools would produce for the community with proceeds going toward the completion of Proctor’s statue and a mausoleum on Lookout Mountain. When Cody residents complained the money would be used only in Denver, the association quickly announced that the funds raised would also assist in the completion of the equestrian statue in Cody. Now Cody and Denver joined hands to complete not one, but two equestrian statues honoring Buffalo Bill in addition to completing the mausoleum at Lookout Mountain.

Despite the joint efforts of Cody and Denver, public support for any Buffalo Bill memorials quickly vanished as America’s involvement in the Great War increased. In December 1917, The Denver Post announced its opposition to any future fundraising for Buffalo Bill memorials until after the war.

On December 7, 1917, Roosevelt wrote to the secretary of the CMA to relinquish his status of membership in the association. “I do not feel that while we are at war I wish to be engaged in soliciting funds for any memorial, or for any purpose not connected with the war,” Roosevelt explained. He did offer some hope for the future though, writing, “When the war is over, if you should desire me again to become a Vice President of the Association, I will be very glad to take the matter up. I believe in a monument along the general lines proposed to me a year ago in connection with Cody and the pioneers of the west but I would wish to know exactly how the proposal is to be carried into effect.”

Due to the public outcry, Mrs. Cody asked that no money be raised for any memorial until the successful completion of the war. Mrs. Cody noted that “Buffalo Bill was first, last and always an American, and he would not wish a cent diverted which could be used for the defense of the country he loved so well.” For the duration of the war, all statues were put on hold.

After the end of World War I, the likelihood of completing any grand memorial for Buffalo Bill in either Cody or Denver seemed doubtful. Agricultural prices dropped severely with an end to wartime demands, plunging the western region into an economic depression. Tourism, though, remained a solid economic resource, partly due to the end of wartime rationing of gasoline and the growing use of the Model T Ford. Both Denver and Cody quickly realized any memorial would be a money-maker, but the funds to build such a project were not readily available. In addition, Theodore Roosevelt passed away on January 6, 1919, and the CMA lost its primary spokesman.

Johnny Baker, Buffalo Bill’s adopted son, did open a small museum at Lookout Mountain and named it Pahaska Tepee. Soon thousands of tourists flocked to see not only Buffalo Bill’s grave but also the museum. With the death of Mrs. Cody in 1921, the residents of Cody panicked, fearing the loss of potential tourist trade connected to the memory of Buffalo Bill. Many residents believed that with Mrs. Cody’s passing, the Irma Hotel would lose its collection of Buffalo Bill paintings, bringing an end to tourists stopping in town.

It was probably at this time that Colorado feared Cody residents would steal Buffalo Bill’s body, since the grave needed to be reopened to inter Mrs. Cody. Stories later burgeoned about the “posse” who tried to steal Buffalo Bill’s body from Colorado. However, the Cody newspaper does not indicate any such posse ever left Cody at this time. Without any viable way of getting the body moved back to Cody, its residents needed to find some way to continue the work of completing the equestrian statue.

Under the vestiges of the BBMA, residents of Cody reorganized their efforts and continued working for an equestrian statue to honor Cody. Buffalo Bill’s niece Mary Jester Allen, who arrived in the Cody area in 1921, used her experience with the Roosevelt Women’s Memorial Association to plan a future memorial for her deceased uncle. Working closely with the BBMA, Allen sought to rejuvenate the plans to erect an equestrian statue in Cody. The association selected New York artist Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney to sculpt the statue. Ironically, Whitney’s daughter, Flora, was previously engaged to Roosevelt’s son, Quentin, who died in World War I.

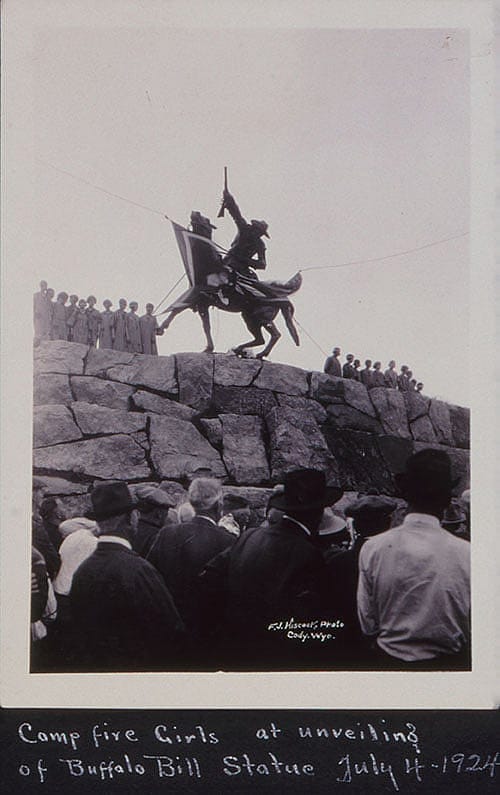

On July 4, 1924, Whitney’s statue, Buffalo Bill—The Scout, was unveiled to a large crowd of Cody residents. Mary Jester Allen continued her efforts to memorialize her uncle and later opened the Buffalo Bill Museum. Cody finally secured its equestrian statue in addition to a lively and growing museum that would become the Buffalo Bill Historical Center, [now the Buffalo Bill Center of the West].

…And while Denver was never able to complete its grandest plans for a mausoleum, the Buffalo Bill Museum and Grave continues to draw locals and visitors alike to Lookout Mountain, the final resting place for the Great Showman.

About the author

Professor Jeremy Johnston is a descendant of John B. Goff, a hunting guide for President Teddy Roosevelt. Johnston grew up hearing many a tale about Roosevelt’s life and times. The “Great Race” story came about as Johnston combined previous research for his master’s thesis with new work as a research fellow of the Cody Institute for Western American Studies at the Center. With the fellowship grant he received, he was able to conduct lengthy research in the McCracken Research Library archives with the help of library staff and Dr. Juti Winchester, then-curator of the Buffalo Bill Museum.

Johnston taught Wyoming and western history at Northwest College for more than fifteen years before joining the staff of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. While a graduate student at the University of Wyoming, Johnston wrote his master’s thesis titled, Presidential Preservation: Theodore Roosevelt and Yellowstone National Park. He is currently a PhD candidate with the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow, Scotland, and is finishing his doctoral dissertation examining the connections between Roosevelt and Cody.

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.