Q Street Buffalo 2

Buffalo

Model of Buffalo for Q Street Bridge; Bison. Model for Q Street Bridge; Q Street Buffalo; Standing Buffalo

During the first decade of the twentieth century, myriad appeals reached the press calling for Americans to take heed of a desperate situation in the West. The region’s symbol (some regarded it as a national symbol), the buffalo, was about to go extinct. Yellowstone National Park and the world’s first conservation organization, the Boone and Crockett Club, had pushed for governmental action to stem the slaughter by poachers in the park, starting as far back as the late 1880s and early 1890s. The result was the National Park Protective Act of 1894 (commonly known as the Lacey Act) which made poaching buffalo in Yellowstone punishable by law. At that time there were about 250 of the shaggy beasts left in the park. By 1908, despite strict new, legally enforceable regulations, that number had dwindled to about twenty.

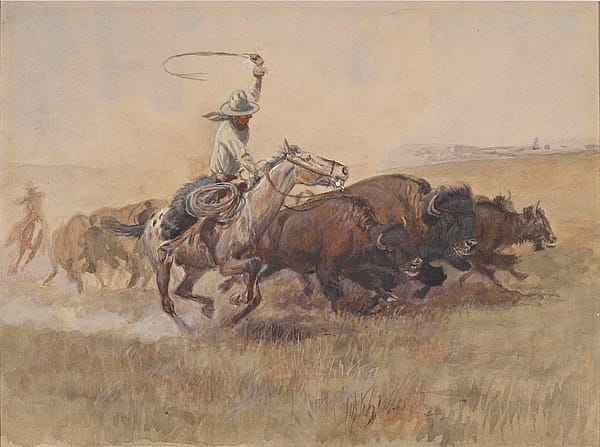

Pablo-Allard Buffalo Drive [Pablo’s Buffalo Hunt], 1909

Watercolor on paper

C.M. Russell Museum, Great Falls, Montana, Museum Purchase (991.19.9) CR.RNR.15

A more substantial herd resided in private hands on a ranch in the Flathead Reservation of Montana, north of the park. Owned by a rancher named Michael Pablo, the herd contained around seven hundred purebred prairie buffalo, and they were for sale for $200 apiece. The U.S. government ironically expressed no interest in acquiring them, so Pablo turned north and sold most of the herd to the Canadian government between 1907 and 1909. Montana artist Charles Russell spent several weeks in 1908 and 1909 watching and recording the so-called Pablo roundup and promoted the thrill of the event in spirited paintings like Pablo’s Buffalo Hunt. [Fig. 1]

Buffalo were much on Proctor’s mind in 1909. He had been invited by President Theodore Roosevelt to modify the fireplace in the State Dining Room of the White House that year. The artist was to sculpt two high relief buffalo heads on the mantel posts. The president, an honorary member of the American Bison Society, saw the buffalo as “the most distinctive game animal on this continent” and worthy of “all good citizens’…efforts for its preservation.”2 It was an emblem of America’s wildlife and of his conservation work as leader of the nation.

Buffalo (Prairie Monarch), 1911.

Bronze, 35 in. (height).

National Museum of Wildlife Art, Jackson, Wyoming. JKM Collection

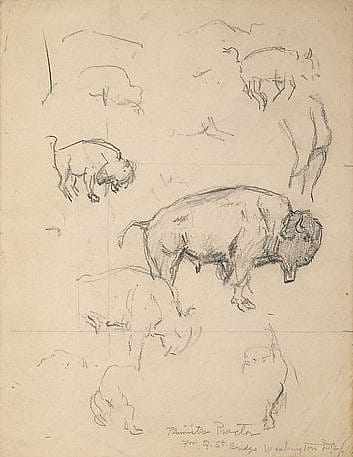

In 1911, Proctor had completed an enlarged version of his first Buffalo sculpture from 1897. The new variation was cast singularly in a four-foot bronze and sold to Herbert L. Pratt for his Glen Cove, New York, estate. As with its predecessor, the bull’s head is lowered, and its pose suggests that the bull is moving forward with a powerful stride. [Fig. 2] Proctor was looking for a fresh model when, around 1910, he received a lucrative commission for four monumental buffalo to decorate a new link between Georgetown and Washington, D.C., the elegantly curved Q Street Bridge. He was no doubt fully aware of the Pablo herd and the Canadian acquisition, and he decided to go in search of a real western buffalo, given that his first buffalo model had been sketched in a Paris zoo. The Canadians had settled the Pablo herd on the prairies of their recently created Buffalo National Park, a two-hundred-thousand acre game preserve near the town of Wainwright in east central Alberta.4 Proctor showed up there in the fall of 1911 to make studies of a few noble bulls for his proposed sculptures.[Fig. 3]

Buffalo (study for Q Street Buffalo), ca. 1911

Graphite on paper, 11 x 8 3/8 in.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York. Gift of Gifford MacGregor Proctor. 1993.80. Art Resource, NY

The resulting four colossal bronze buffalo were put in place in 1914.5 Their heads were erect and their stance one of alert, staid reserve. The two that faced to the left were called Buffalo I and the two that faced to the right got the titles of Buffalo II. Using the 13-inch maquette for Buffalo I, which Proctor copyrighted in 1912, the artist had Roman Bronze Works start making tabletop-sized bronzes. The earliest known casting of the Roman Bronze Works production came out of the foundry in 1913, an order from Proctor’s patron George D. Pratt, who donated it to the Brooklyn Museum in 1914. [Fig. 4] It has several peculiarities, including a misspelling of the artist’s last name, but most important is a detail on the top of the artist’s base. There, emerging from the earth between the beast’s hind legs, are the remnants of a buffalo skull. [Fig. 5]

Buffalo, 1913

Bronze, 13 3/8 in. (height)

Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, New York. Gift of George D. Pratt. 14.565

This element, which does not appear in other known castings of the work including the monuments, suggests that Proctor recognized the importance of the preservation efforts that were underway. He was living at the time in New Rochelle, New York, just above the city and no doubt read about them in the New York Times, and even possibly visited Charles Russell’s exhibition, The West That Has Passed, at the Folsom Galleries in New York in 1911, during the spring and summer before Proctor’s trip to the Canadian West. 6

Buffalo (detail — base), 1913

Bronze

Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, New York. Gift of George D. Pratt. 14.656

He would have seen Russell’s bronze, Nature’s Cattle, freshly minted by Roman Bronze Works that spring. Nature’s Cattle carries the message of promise for the beleaguered buffalo, showing a healthy family group crossing the prairies. [Fig. 6] While at once sentimental, Nature’s Cattle is also prescient, providing a testament of hope for the buffalo’s future. Proctor’s new Buffalo, standing astride a token of a diminished past represented by the skull, evokes the same affirming message, that the buffalo is proud, commanding, and resilient when provided proper stewardship, and that it represented a national symbol worthy of the artist’s finest work.

Nature’s Cattle, 1911

Bronze, 4 3/4 in. (height)

Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. W.D. Weiss. 27.97.7

Subsequent castings of the work, whether produced by the Roman Bronze Works, Gorham Co. Founders, [Fig. 7] or Verbeyst Foundeur in Brussels, have bases that are essentially flat and completely devoid of the skull. There is nothing in the artist’s records to explain why the change was made. Perhaps viewers felt it was difficult to determine what the skull was, and to simplify the matter it was removed. With its elimination, however, some of the poignancy of the piece was lost.

Buffalo, (model for Q Street Buffalo, ca. 1927

Bronze, 13 1/4 in. (height)

The Cleveland Museum of Art. Gift of George D. Pratt. 1927.291

Proctor began exhibiting what he called Bison, Model for Q Street Bridge, at the Canadian Art Club in early 1913. 7 Later that year it appeared as a featured piece in his show in the new galleries of the Gorham Co. Founders in New York.8 It went on to see a long history of showings whenever Proctor exhibited large samplings of his work. More than a dozen life-time castings are known to survive today including a founder’s master model or pattern at the University Museums, University of Delaware.

By Peter H. Hassrick

Endnotes

- Ernest Harold Lawson, “The Fight to Save the Buffalo,” Country Life in America, 3 (January 1908), 348.

- Ibid, 295.

- See Peter H. Hassrick, Wildlife and Western Heroes: Alexander Phimister Proctor, Sculptor (Fort Worth: Amon Carter Museum, 2003), 130 – 131.

- Another article of the time that Proctor might well have seen and that gave the history of the Canadian preserve was Sumner W. Matteson, “Doom of Extinction Averted from the American Bison,” Leslie’s Weekly, CVI (February 27, 1908), 203.

- Hassrick, Wildlife and Western Heroes, 169.

- Arthur Hoeber, “Cowboy Vividly Paints the Passing Life of the Plains,” New York Times (March 19, 1911).

- The Canadian Art Club, Sixth Annual Exhibition (Toronto, 1913), no. 75.

- Gorham Co. Founders, Exhibition of Bronzes and Plaster Models by A. Phimister Proctor (New York, 1913), no. 14.