Panther 2

Panther

Prowling Panther; Charging Panther; Stalking Panther; Crouching Panther; Panther-Fate; Fate; Roosevelt Panther

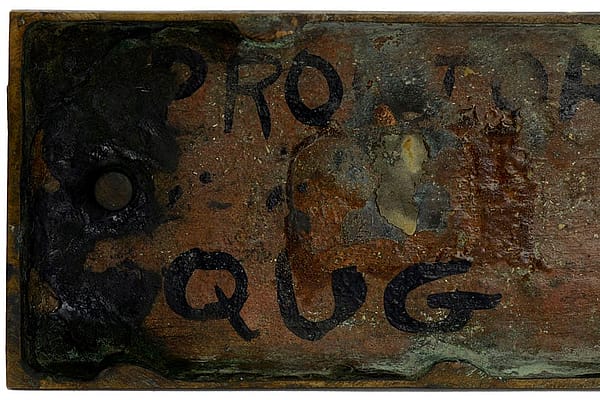

Proctor and World’s Fair Panther, 1893

Photograph b&w

Alexander Phimister Proctor Collection, MS242, Harold McCracken Research Library, Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming. P.242.429

Proctor began to dream of exploring in art the mountain lion of the Rockies during one of his hunting trips in the Flat Tops of the Colorado Rockies in the summer of 1887. He shot and killed at least a couple of bears, numerous deer and elk, and an adult panther. The lion was perhaps his favorite trophy. He sketched it, skinned it, and then had the pelt packed up to take back to his studio at the Art Students League in New York.1 He continued to pursue his passion for these wild cats at New York’s menagerie, just a few blocks away from his studio. Using various studies, he made his first model in wax at the Art Students League.2

When, in 1891, Proctor received an invitation to model monumental plaster sculptures of western animals as decorations for the grounds of the World’s Columbian Exposition, one of the subjects he chose was his western mountain lion. [Fig. 1] It may have looked something like the first wax model that he had fashioned in New York, but that is not known. What is for certain is the impression it made on the visitors. In what one reviewer referred to as “Nature’s mountain school, among the wild play-fellows of canyon and forest,” Proctor had learned from “the lion’s roar or the cunning panther’s plaintive cry” the essence of wilderness. Yet, beyond that, through his personal studies, he had also become a savant of the cat’s “anatomy, which is a more valuable accomplishment for a sculptor.”3

Panther (one of Proctor’s first models), 1893

Photograph, b&w

Alexander Phimister Proctor Collection, MS242, Harold McCracken Research Library, Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming. P.242.432

As a subsequent tabletop bronze, this work seems to have undergone more alterations over the long course of its life than any other Proctor sculpture. Although the work was copyrighted under the title Panther in 1897, most early versions of the piece are marked with the dates “1891–1892.” The first known record of the work being cast in bronze appeared in the Chicago Inter Ocean on January 1, 1893, which reported its having been “recently completed in bronze.”4 That 1892 casting (current location unknown), also referred to simply as Panther, was exhibited in the American art section of the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 and the next spring in New York City at the Society of American Artists.5

At the showing in New York, Proctor’s early venture in animalier bronze drew a good deal of notice. When it was seen in the Society of American Artists exhibition, one reviewer admired Panther for its “rough energy” and “truth,” another for its evident fierceness, and a third for its anatomical correctness.6 Proctor could not have asked for more complete coverage or a more thorough assessment of his skills. In a comparison of what is thought to be the plaster for this early version (preserved in an extant photograph) [Fig. 2] to later iterations, the tail seems to droop, the body is more elevated, the foreleg is attenuated, and the head is substantially smaller.

When the Proctors moved to Paris in the fall of 1893, they took with them what the artist referred to as a “three-foot plaster model of the stalking panther.”7 They must have left the first bronze casting at home to be shown in New York during their absence. But Proctor felt that he could make

improvements on the piece, ultimately by studying the anatomy of a Parisian alley cat, and a new model was thus created in France. So pleased was Proctor with the subsequent revisions that he exhibited a “sketch” of it, presumably a plaster, in the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in 1895.8 He went to the expense of having that second version cast in bronze. Proctor referred to it, albeit incorrectly, as “our first real bronze.”9

Panther (views 1 and 2, second version), ca. 1894

Bronze

Nordica Homestead Museum, Farmington, Maine

This may be the bronze owned by the famous operatic soprano Madame Lillian Nordica (1857–1914), who was in Europe performing that year. That casting has a unique marking on the base, not found on other castings, in which it is signed and dated 1894. [Figs. 3A and 3B] The head is shorter and less streamlined, the lower jaw does not protrude, the tail is straighter and bends more abruptly upward at the end, and the left forepaw is pointed outward to the left, quite differently from the later castings as well, suggesting that subsequent alterations were made after Proctor’s second attempt to further perfect the pose. A second casting of this version in bronze was exhibited in Philadelphia in 1899.10

When the third and most commonly known of the Panther versions was first modeled is not known. It varies from the earlier known version in that the tail is lowered and more curved, the left forepaw is placed in line with the cat’s body, which is closer to the ground, and the jaw is brought forward in line with the nose. Proctor exhibited a casting under the title Panther-Fate in the U.S. Pavilion at the Paris Exposition in 1900,11 and again—possibly as a plaster—under the title Charging Panther in the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo in 1901.12 One sand casting of this work, currently in the collection of the Portland Art Museum in Oregon, was marked “1901” on the base, which suggests that this was possibly the inception date of the third version. It was cast by Gorham Co. Founders after 1913. At about the same time, Proctor started casting lost-wax versions of the bronze using the Roman Bronze Works. The earliest known example of this, cast number 4 produced in about 1902, is in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. [Fig. 4] Between 1900 and 1915 he cast twenty-two pieces with the Roman Bronze Works.13

Stalking Panther, ca. 1902

Bronze, 9 1/2 in (height)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York. Purchase, William Cullen Bryant Fellows Gifts and Maria DeWitt Jesup Fund, 1996. 1996.561. Art Resource, NY

In 1908, at Proctor’s major retrospective exhibition in New York’s prestigious Montross Gallery, the famous silversmith and brother-in-law of Proctor’s friend Alden Sampson, Henry Blanchard Dominick, loaned a casting called Prowling Panther to the show. In the same exhibition, suggesting that a new variant of the piece was under way, Proctor exhibited what might be assumed to be the genesis of another, fourth version under the title “Prowling Panther: Later Study of the Above.”14 In his magazine, The Craftsman, Gustav Stickley referred to Proctor’s show at the Montross Gallery as “one of the most important exhibits of the season,” claiming also that his “‘Prowling Panther’ . . . is considered second to no other bronze in its vivid suggestion of swift stealthy action.”15 Presumably the review concerns the bronze casting, version four.

Stalking Panther, ca. 1905 — 1913

Bronze, 10 1/2 in (height)

National Gallery of Art, Corcoran Collection, Washington, DC. Bequest of James Parmelee. 2015.19.3686

These later castings are somewhat sleeker than the third version. The hump over the panther’s front shoulder is less accentuated, and the rear hip is lowered. As if to push the cat forward, the tail lifts slightly more upward than in earlier castings. [Fig. 5]

The earliest documented example of what is probably this fourth variation was a sand-cast bronze produced by the New York foundry Jno. Williams, Inc., and acquired by Theodore Roosevelt in February 1909. The artist had received a letter from his close friend Henry L. Stimson, whom President Roosevelt had appointed as U.S. district attorney for the Southern District of New York. Stimson had been asked by members of the president’s “Tennis Cabinet” to acquire a casting of the Panther to be given to Roosevelt as a token of their respect for and appreciation of the president’s years of service as the nation’s leader. Proctor was thus called upon to gratify the outgoing president of the United States, his own friend and supporter. Presented on February 26, 1909, the casting still resides at Sagamore Hill, Roosevelt’s Oyster Bay, New York, home.16 Roosevelt thereafter made the Panther a national symbol of power and fortitude.

Shortly on the heels of that commission, events moved forward that resulted in another casting of the fourth version, finding a home at the National Gallery of Canada in 1909. Proctor had become a member of the Canadian Art Club that year and was invited in March to show with his new associates at their second annual exhibition in Toronto. He displayed twelve bronzes, including a casting of Prowling Panther.17 The club purchased this Jno. Williams, Inc., casting and donated it to the National Gallery of Canada in honor of its new member.

The Montross Gallery continued to feature Proctor’s bronzes into the early teens.18 But in 1913, the Gorham Company took center stage in Manhattan when, in its splashy new downtown gallery, Gorham presented a monumental one-man exhibition of Proctor’s work. Among the twenty bronzes and twenty-five plasters was a bronze of what the catalogue called Charging Panther.19 Orders could be taken, once that show piece was sold, and current research indicates that more than a half-dozen Gorham sales, mostly of sand-cast bronzes, occurred from that date forward into the 1940s. The same research notes that there are three known sand-cast bronzes produced by Jno. Williams Founders of New York between about 1900 and 1905, and another twelve known castings made after the foundry was incorporated as Jno. Williams, Inc., in 1905. Some of the latter are inscribed with cast numbers ranging from 3 (Agnes Etherington Art Centre) to 32 (private collection, Michigan), suggesting that Jno. Williams, Inc., was a major producer of these works. In addition, at least twenty-two, in lost wax, were produced by the Roman Bronze Works between 1900 and 1915.20

Panther, ca. 1925

Bronze, 11 1/4 in (height)

Belle Clegg Hays, Comptche, California

About a dozen years later, in 1922, Proctor again undertook modifications to the Panther. One result of this effort has been referred to as the remodeled large version, while the other was a substantially smaller interpretation. The former variation was made to satisfy the artist, who had evidently tired of the original pose, and the latter was initiated to accommodate patrons by introducing a work of similar spirit but at a reduced price.

The remodeled large version was sculpted in Palo Alto while Proctor was putting the finishing touches on a maquette for the monument The Pioneer Mother in Kansas City. The sculptor, ever conscious of costs, wished to realize serious economies by having the monument pointed up and cast in Italy. To that end he moved back to New York in the fall of 1925 to clean out his studio there and prepare for the trip to Europe. In early October, while Proctor was still in New York, Theodore Roosevelt’s son Kermit and his friend Alfred Ernest Clegg visited the studio.21 Clegg wanted to buy a casting of the Panther like the one Kermit’s father had received as a gift in 1909. Proctor encouraged him to purchase a casting of the newly remodeled version from Roman Bronze Works. [Fig. 6] Clegg not only did that but also ordered castings of the Indian Warrior and the maquette size of the Kansas City Pioneer Mother. All three sculptures were passed down in the Clegg family.

Panther (small version), ca. 1922

Plaster, 6 7/8 in. (height)

Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming. Gift of A. Phimister Proctor Museum with special thanks to Sandy and Sally Church, 11.06.384

The remodeled large version of the Panther is altered in a number of ways from its earlier prototype. In the new model the panther’s face is shortened, resembling the first bronze castings of the piece. The forward shoulder is given more mass, the back left leg is strengthened and shortened, and the tail is somewhat further extended.

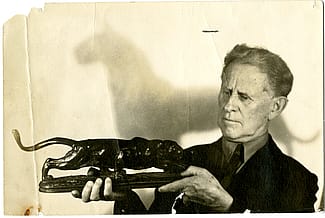

Proctor reviewing small Panther, 1943

Photographer, b&w

Alexander Phimister Proctor Collection, MS 242, Harold McCracken Research Library, Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming. P.242.435

The small version of the Panther [Fig. 7] is reduced in size by half, measuring in length about 19 inches instead of 39 inches. These bronzes, quite rare today, were derived from a model conceived in 1922, the same date as the remodeled large version.22 Cast in the 1920s from a plaster used by at least two foundries, the new model of the wild cat gratified the artist for nearly three decades and brought closure to Proctor’s experience begun sixty-five years earlier.[Fig. 8] That hunting adventure in the Flat Tops of western Colorado in 1887, where—alone in the wilderness—he shot a mountain lion and spent several days sketching it in his hunting camp, was still a fond memory. Proctor’s passion for and identification with one of nature’s most iconic hunters had served him as a sculptor throughout his career. The multiple variations that he imposed on the theme only clarified how vital that experience and that model were to the development of his life’s oeuvre.

By Peter H. Hassrick

Endnotes:

- Katharine C. Ebner (ed.), Sculptor in Buckskin: The Autobiography of Alexander Phimister Proctor (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2009), 83–84.

- Ibid., 88.

- “About the Studios: Phimister Proctor Is a True Natural Sculptor,” Chicago Inter Ocean (January 1, 1893).

- Ibid.

- World’s Columbian Exposition, 1893, Official Catalogue: Fine Arts, no. 100a; and Sixteenth-Annual Exhibition of the Society of American Artists (New York: Society of American Artists, 1894), no. 313.

- See “The Chronicle of Arts,” New-York Daily Tribune (April 10, 1894); “Society Show Soon to Close,” New York Times (April 18, 1894); and “Juggling with Brushes . . . ,” Morning Journal (March 18, 1894). I am grateful to Thayer Tolles for bringing these reviews to my attention.

- Ebner, Sculptor in Buckskin, 102.

- See Peter Hastings Falk (ed.), The Annual Exhibition Record of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Vol. 2, 1876–1913 (Madison, CT: Sound View Press, 1989), 390.

- Ebner, Sculptor in Buckskin, 102. A second bronze, identical except for the date, now in a private collection, was shown in 1899 at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. See Falk, Annual Exhibition Record of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 2:390.

- Falk, Annual Exhibition Record of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 2:390. This casting, with a Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts sticker, was sold by the Thomas Nygard Gallery to a private collection in 2011.

- Official Illustrated Catalogue: Fine Arts Exhibit, United States of America, Paris Exposition of 1900 (Boston: Noyes, Platt & Co, 1900), no. 47.

- Pan-American Exposition: Catalogue of the Exhibition of Fine Arts (Buffalo: David Gray, 1901), no. 1636.

- See note 20.

- Catalogue of Sculpture, Bronzes, Water Colors, and Sketches Exhibited by A. Phimister Proctor (New York: Montross Gallery, 1908), nos. 4 and 4a.

- “Music: Drama: Art: Reviews,” The Craftsman, 15 (January 1909), 501.

- See Ebner, Sculptor in Buckskin, 196.

- Canadian Art Club: Second Annual Exhibition (Toronto: Canadian Art Club, 1909), no. 51.

- See Exhibition of Sculpture (New York: Montross Gallery, 1912).

- Exhibition of Bronzes and Plaster Models by A. Phimister Proctor (New York: Gorham Co., 1913), no. 8.

- The Roman Bronze Works ledger books at Amon Carter Museum record eight castings, numbers 8 through 15, made between 1904 and 1905 alone. Subsequent castings, up to number 22, were noted in the records up to 1915. If it can be assumed that the Roman Bronze Works began casting Panthers in around 1900, the firm averaged about three castings every two years for fifteen years.

- This story is recounted in Ebner, Sculptor in Buckskin, 196. I am grateful to Belle Clegg Hays, A. C. Clegg’s daughter, for confirming the story from her family’s perspective.

- Proctor seems to have retained the 1897 copyright for both the remodeled and the small version. An article about his 1923 Stendahl Gallery exhibition in Los Angeles, in which he showed both new versions, mentions specifically that the small work had been first produced the previous year. See “Proctor, a Sculptor of Unusual Power,” Los Angeles Times (April 1, 1923).