Wonders of the World – the “Prairie Beauties”

“Wonders of the World” by Sarah Wood-Clark, former assistant registrar, was originally published in a 1983 Buffalo Bill [Center of the West] newsletter.

Billed as “Prairie Beauties” and “Beautiful, Daring Western Girls,” they came from widely varied backgrounds to astonish and delight Eastern and European audiences with their riding, roping, and other non-typical feminine skills. Annie Oakley, performing with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, may have been the best known female personality of her day, but she was not the only woman in that branch of show business.–

Throughout the era of the successful Wild West shows, women filled many roles as arena performers. The usual assumption is that these were the liberated ladies of the day. Whether or not that is true, however, is open to debate.

Little was said in the literature of the period about Wild West women being equals of their male peers, yet Buffalo Bill himself was outspoken about it. In several newspaper interviews he stated that American women had more freedom of development than their European sisters and were as good or better than men.

Whether or not his competitors followed suit is not known, but if contemporary contest prizes are any indication, his wage practices were not unusual. Women’s prizes sometimes ran higher than men’s for the same events, even though there were some differences in the rules. For example, lady bronc riders, fairly common after about 1895, were allowed to hobble their stirrups (tie them under the horse). This was allegedly an advantage, though potentially dangerous. In the show arena, at least, women participated with the men in riding, trick riding, racing, bronc and steer riding, roping and bull-dogging, although their numbers, particularly in the more strenuous events, were never great. The Miller Brothers and Arlington 101 Ranch Real Wild West note their cowgirls in the show program, saying “…in affairs where skill is the chief qualification she has an equal chance with her brothers.”

Whether or not women performed chores on the show lot, as most of the men did, is difficult to determine. Few women were engaged on grounds crews or in the necessary cooking and laundry chores. Former Buffalo Bill’s Wild West bronc rider Harry Webb recalls that, aside from arena appearances the women had “no real duties.” Orillia Downing Hollister, a lady rider from Cody, wrote that the women were privileged to have grooms take their horses to the show lot.

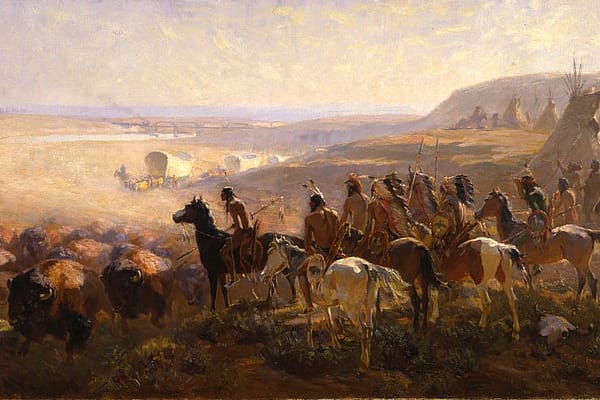

As the era progressed, the women and their show roles changed. In the early years they played traditional roles, as wives of homesteaders and victims of Indian attacks. When they rode, they rode sidesaddle and wore the fashionable long skirts and shirtwaist blouses. By the 1890s, as bronc and trick riders, they had adopted divided riding skirts and heavily adorned cowboy style accessories, and they rode astride. Their clothing and riding style, not being widely accepted in American society, were subjects of constant comment from the news media.

By and large, the women of the Wild West fell into two categories as portrayed in the media and promotional literature of the time. First was the “Prairie Beauty” type, featured in vignettes on the program as decorative and domestic. Second was the “hardened western woman” who could ride a bronc and defend a wagon train against Indian attacks simply because of the hardships she had been required to face on the western frontier.

In reality, many were simply expanding their own experiences and career opportunities by exhibiting skills they acquired out of necessity. Others were attracted by the glamour of the show circuit. Some were merely following husbands. They did not consider themselves liberated or role models for other women.

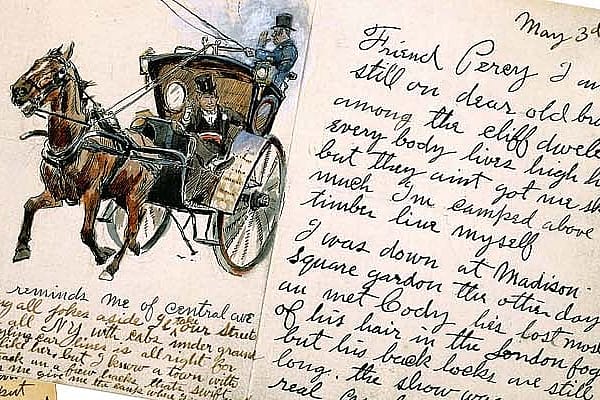

Perhaps they were as surprised by all the attention as Orillia Downing Hollister was when she wrote, “…people thought I was one of the wonders of the world.”

Written By

Michaela Jones

Michaela, a Cody, Wyoming native, is the Centennial Media Intern at the Center of the West for the summer of 2017. She recently graduated from the University of Wyoming with a bachelor's degree in English and minors in professional writing and psychology. She's interested in writing for digital spaces, producing social media content, and learning about technology's impact on communication. In her spare time, she enjoys reading non-fiction, exploring the mountainous Wyoming regions, and spending time with family and friends.