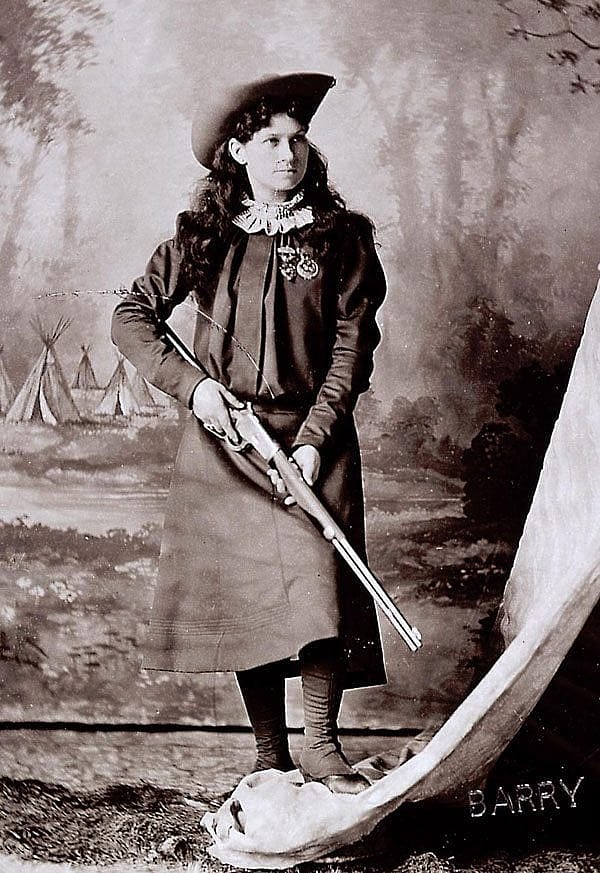

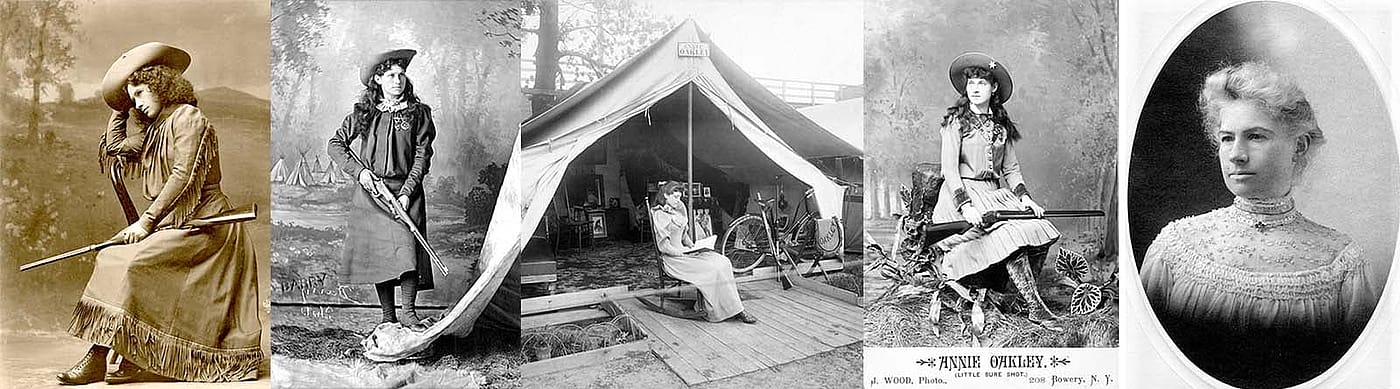

Annie Oakley

Annie Oakley

(1860 – 1926)

Annie Oakley was born Phoebe Ann Moses—called Annie by her family—on August 13, 1860, in Darke County, Ohio. This unassuming woman, who would perform before royalty and presidents, came from humble beginnings. When Annie was 6, her father, Jacob Moses, died of pneumonia—leaving her mother, Susan Wise Moses, with six children and little else. Annie’s mother remarried but her second husband, Dan Brumbaugh, died soon after, again leaving her with a new baby.

At the age of 8 or 9, Annie went to live with Superintendent Samuel Crawford Edington’s family at the Darke County Infirmary, which housed the elderly, the orphaned, and the mentally ill. In exchange for helping with the children, Annie received an education and learned the skill of sewing from Mrs. Edington, which she would later use to make her own costumes. Perhaps this early experience of working in such a sobering place aroused Annie’s lifelong compassion for children. She remained with the Edingtons until she was 13 or 14.

When she returned to her family, Annie’s mother had married a third time to Joseph Shaw. Even with this remarriage, the family finances were marginal. Annie used her father’s old Kentucky rifle to hunt small game for the Katzenberger brother’s grocery store in Greenville, Ohio, where it was resold to hotels and restaurants in Cincinnati, 80 miles away. Annie was so successful at hunting that she was able to pay the $200 mortgage on her mother’s house with the money she earned. She was 15 years old.

Her noted shooting ability brought an invitation from Jack Frost, a hotel owner in Cincinnati who had purchased her game, to participate in a shooting contest against a well-known marksman, Frank E. Butler.

Butler was on tour with several other marksmen. While on the road, he typically offered challenges to local shooters. Annie won the match with twenty-five shots out of twenty-five attempts. Butler missed one of his shots. This amazing girl entranced Butler, and the two shooters began a courtship that resulted in marriage on August 23, 1876.

Annie and Frank Butler first appeared in a show together May 1, 1882. Butler’s usual partner was ill and Annie filled in by holding objects for Frank to shoot at, and doing some of her own shooting. It was at this time that Annie adopted the stage name of Oakley. Off stage, she was always Mrs. Frank Butler. For the next few years, the Butlers traveled across the country giving shooting exhibitions with their dog, George, as an integral part of the act.

At a March 1884 performance in St. Paul, Minnesota, Annie befriended the Lakota leader Sitting Bull. The victor over George Armstrong Custer at the 1876 Battle of Little Big Horn, Sitting Bull was impressed with Oakley’s shooting, her modest appearance, and her self-assured manner. Although Sitting Bull was still a political prisoner at Fort Yates, he was in town for an appearance, and had arranged to meet Oakley. They became fast friends. It was Sitting Bull who dubbed her “Little Sure Shot.”

In 1884, the Butlers joined the Sells Brothers Circus as “champion rifle shots,” but only stayed with the circus for one season. After a brief period on their own, Butler and Oakley joined Buffalo Bill’s Wild West in 1885. This was a significant turning point in Annie Oakley’s life and in her relationship with Butler. Until this time either Butler had received top billing or they had shared the limelight. However, with the Wild West, Oakley was the star. It was her name on the advertising posters as “Champion Markswoman.” Butler happily accepted the position as her manager and assistant. Oakley and Butler prospered with the Wild West and remained with the show for seventeen years.

In 1887, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West toured England to join in the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria. When the show opened that May, Oakley was the subject of considerable press due to her shooting skills and presence. This tour also helped Oakley increase her growing collection of shooting medals, awards, and trophies.

When the Wild West returned to Europe in 1889, Oakley had become a seasoned performer and earned star billing. The troupe stayed in Paris for a six-month exhibition, and then traveled to other regions of France, Italy, and Spain. Oakley proved especially popular with women, and Buffalo Bill made the most of her fame to demonstrate that shooting was neither detrimental, nor too intense for women and children.

Oakley and Butler’s desire for less extensive traveling, as well as a serious train accident that injured her back, caused them to leave the show in 1901. However, she continued to perform and eventually joined another wild west show, “The Young Buffalo Show,” in 1911. During this period, Butler signed a contract as a representative for the Union Metallic Cartridge Company in Connecticut. This was a position that allowed both Butler and Oakley to make endorsements for the company and to continue their shooting exhibitions. Finally, in 1913, the couple retired from the arena and settled down in Cambridge, Maryland.

While in Cambridge, the Butlers welcomed a new member into their family, their dog Dave. Named for a friend, Dave Montgomery of the comedy team of Montgomery and Stone, Dave was to be a constant companion to the Butlers. When they returned to the arena, Dave was to become an important part of the act—one trick was Annie shooting an apple from the top of Dave’s head. In 1917, they moved to Pinehurst, North Carolina. That same year, Buffalo Bill Cody died. Annie Oakley wrote a touching eulogy for Cody, and the passing of a golden era.

The United States was pulled into World War I in 1917, and Oakley offered to raise a regiment of woman volunteers to fight in the war. She had made the same offer during the Spanish-American War; neither time was it accepted. She also volunteered to teach marksmanship to the troops. Oakley gave her time to the National War Council of the Young Men’s Christian Association, War Camp Community Service, and the Red Cross. Dave became the “Red Cross Dog” by sniffing out donations of cash hidden in handkerchiefs.

Oakley began making plans for a comeback in 1922. Attracting large crowds in Massachusetts, New York, and major cities, she had plans to star in a motion picture. Unfortunately, at the end of the year, she and Butler were severely injured in an automobile accident. It took Oakley more than a year to recover from her injuries. By 1924, she was performing again, but her recovery did not last long. By 1925, she was frail and in poor health. She and Butler moved to her hometown in Ohio to be near her family. They attended shooting matches in the local area, and Oakley began to write her memoirs, which were published in newspapers across the country.

In 1926, after fifty happy years of marriage, the Butlers died. Annie Oakley died on November 3 and Frank Butler died November 21, within three weeks of each other. Both died of natural causes after a long and adventuresome life.

From her humble roots as Phoebe Ann Moses to taking center stage as Annie Oakley—champion shooter and star of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West—this remarkable woman is remembered as a western folk hero, American legend, and icon. Throughout her career, Oakley maintained her dignity and propriety while quietly proving that she was superior to most men on the shooting range. Thanks to Hollywood and history, the legend of Annie Oakley endures into the twenty-first century through motion pictures, television, on the stage, in history books, and in museums.

Interested in learning more about Annie Oakley?

Take a look at our suggested reading list.

Explore our McCracken Research Library’s web pages.

Browse the Buffalo Bill Center of the West’s online Museum Store for items related to Annie Oakley.

Find out more about Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and other shows.

You may also enjoy these other books on Wild West shows.