Cody and Wanamaker: The Foundation of American Indian Citizenship – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Winter 2003

Cody and Wanamaker: The Foundation of American Indian Citizenship

By Katrina Krupicka

Former Intern, Buffalo Bill Museum

The life of W. F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody has been the topic of myths and legends for over a century. Incidents were fabricated and distorted to entertain the American public as well as the international community. Buffalo Bill himself helped to perpetuate many of the myths, giving him a legendary status that continues to fascinate audiences today.

No strangers to contradiction and confusion, historians attempting to unravel the life story of Buffalo Bill have a daunting task. After wading through the misconceptions, however, the story of a profoundly thoughtful and compassionate individual emerges; someone who was thoroughly interested in the common good for man, regardless of race, class or gender. A primary example of Buffalo Bill’s sincerity is evident in his involvement in the spirit behind the Wanamaker Expeditions that took place in the early twentieth century.

The Wanamaker Expeditions epitomized Cody’s dream to create a stronger relationship between American Indians and whites. Lewis Rodman Wanamaker was the son of the business tycoon John Wanamaker. In 1907, he became heavily involved in the managing of his father’s department stores, one in Philadelphia and one in New York City. Despite having the name “Wanamaker” associated with the expeditions, the true force behind them is embodied in the man Dr. Joseph K. Dixon. A self-proclaimed academic doctor and a retired minister, Dixon was hired as a lecturer for the educational bureau of the Wanamaker department stores.[1] His lectures had an increasing tendency to focus on the topic of Native Americans. Eventually he was able to convince his employer to sponsor expeditions in 1908, 1909, and 1913 to gather “educational” information on the race.

The purpose of the expeditions was to record the history of the American Indian before the ‘race’ vanished from the countryside. While the truth of such an occurrence holds little merit today, it was a strong belief that captured the imagination of educated whites on the East Coast. During the first two expeditions Dixon took photographs and made motion pictures, the most famous one being a production of the epic poem The Song of Hiawatha filmed at Crow Agency in Montana.[2]

The idea to erect a memorial to the American Indian in New York Harbor evolved from the first two expeditions. Identified in a newspaper article from May 12, 1909, as being a statue of “bronze and as great, if not greater in size than the Statue of Liberty,” the memorial would stand for “the welcome given in years gone to the early settlers by the red man and it will be a sign to present and future generations that the first American welcome is as hearty in perpetuity.”[3] A dinner held in honor of Col. W.F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody served as the announcement of this monumental endeavor.

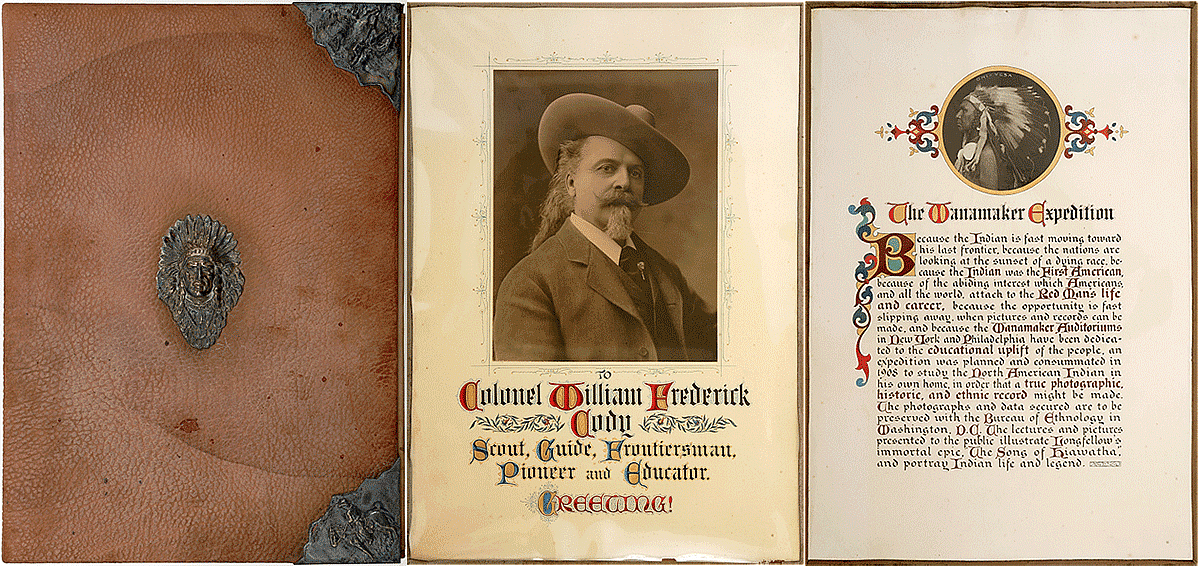

The direct connection between Buffalo Bill and the Wanamaker Expeditions is difficult to gauge in the time prior the banquet. Given in his honor, its purpose was “to express publicly the appreciation of Colonel Cody’s services as a scout and a fighter, and more than all, to call upon him to tell as no other man could the good side of the Indian.”[4] At the banquet, Buffalo Bill was presented with the Wanamaker Tribute Portfolio. The portfolio, with a silver buffalo head on its buffalo hide cover, was actually presented to Cody by General Nelson A. Miles and Dr. Dixon. Six pages contained the text of the tribute to Cody, commending him on various aspects of his life and career.

The text of the tribute credits Cody with fulfilling the daunting task of being a societal idol of the American West. He is praised for his character as an individual, for his work as a plainsman, scout and guide for the Army and for fighting for the rights of the American Indian. The Wanamaker Tribute goes on to identify Cody with establishing a model for Americans as a true frontiersman. Through the performances of his Wild West show, he was preserving a way of life as well as educating its spectators and boosting pride in the United States.

Along with the other elements highlighted in Col. Cody’s career and characteristics, the one most emphasized by the contents of the portfolio is his work in creating a harmonious relationship between Indians and whites. It commended Buffalo Bill for his “honorable work among the Indians, in which [he] not alone gave distinguished service to the government, saving the lives of hundreds of soldiers and settlers, but where [he] also won such respect and love from the Red Man as to eclipse in his regard all other white men…”[5] The text of the tribute continues on, not only praising Buffalo Bill for his extraordinary life but also revealing his contribution in perpetuating sentiments held by the general American public: “Because, by reason of your knowledge and strength, and by reason of the Indian’s love for and trust in the Man who has never deceived him, you have built up and presented to the World the great and enduring picture of those old Stage Coach Days, representing in life the most vivid and exciting action of an epoch of American history, long since closed, and exhibiting the character, habits, and skill of a race that will soon become extinct…”[6] The other pages included a report of the Wanamaker Expedition made in 1908 and photographs taken during the trip.

While the construction of the statue never reached completion, the spirit behind the Wanamaker Expeditions, the Wanamaker Tribute portfolio, and the proposed National Indian Memorial resulted in a document significant to American history: The “Declaration of Allegiance of the American Indians to the United States.” The idea, evolving in 1909 at the last Council of Chiefs, was to create a declared peace between Indian tribes and all other people in the country. The allegiance centered on the symbol of the American Flag. Dixon felt that if the American Indians accepted the flag as a unifying entity, they would have a constant reminder of their loyalty to the United States.

President William Howard Taft agreed to a signing ceremony at Fort Wadsworth in New York City, which some participants viewed as being a dedication ceremony of the National Indian Monument. Thirty-two chiefs were present at the ceremony to sign the allegiance, which was a consolidation of their own individual allegiances: “We, the undersigned representatives of the various Indian tribes of the United States, through our presence and the part we have taken in the inauguration of this memorial to our people, renew our allegiance to the glorious flag of the United States, and offer our hearts to our country’s service….”[7] Many tribal leaders believed that the document was a treaty. Several skeptical individuals viewed the document as a publicity stunt by Rodman Wanamaker and other East Coast businessmen.

During the 1913 Wanamaker Expedition, Joseph Dixon, with permission from newly elected Woodrow Wilson, traveled to eighty-nine Indian reservations to perform signing ceremonies. By the end of the expedition, the document had 900 signatures, representing 189 American Indian tribes. The signed Declaration became a lobbying tool for Dixon to push Congress to grant Indians citizenship in the United States. Indian veterans returning from World War I, however, were the real catalyst for granting citizenship to Native Americans, but Dixon would take credit for the legislation for the rest of his life.[8]

Citizenship was not universally welcomed among the American Indian population. Having recently received ownership of property, many Indians viewed the citizenship has a ploy to exert taxation, thus enforcing a new type of captivity.[9] In fact, Dixon’s signing expedition was met with a great deal of resistance across the country, as many Indians simply used the ceremony as a sounding mechanism for their own dissatisfactions with the United States government. The rights of citizenship for American Indians continue to be questionable into the twenty-first century. Calls for land rights, sovereignty, and acknowledgement of past treaties are just a few of the topics of the dynamic discourse today.

It is difficult to accurately assess a single causation of Indian citizenship in the United States. Instead, several different elements helped to create the roots for the movement. What can be properly conjectured is that W.F. Cody had a great deal of influence in establishing a mood for change. Buffalo Bill’s dedication to Indian culture and rights in the United States was an obvious element in his Wild West Show. By creating an awareness of the importance of Indians in American society, Cody was able to be a catalyst for significant American Indian legislation. He was successful in providing the government and society with a foundation upon which could be built a new relationship with American Indians. The Wanamaker Portfolio is a significant symbol of Cody’s crucial role in the emergence of a new state of mind among the American public.

Notes:

1. Lindstrom, Richard, “‘Not from the Land Side, But from the Flag Side’: Native American Responses to the Wanamaker Expedition of 1913,” Journal of Social History, no. 30(1) (1996):211.

2. Barsh, Russel Lawrence, “An American Heart of Darkness: The 1913 Expedition for American Indian Citizenship,” Great Plains Quarterly, Vol. 13(2) 1993), 91–115. Dixon exercised a high level of influence over the topic of the multitudes of photographs taken during the expeditions. He would have Indians dress in native dress, depicting a race that desperately needed the helping hand of the white man. This would come to be one of the many ironies of the expeditions, especially since many of the Indians who were photographed were highly educated men with impeccable English that felt awkward in the native dress.

3. Newspaper article titled “Statue of Indian for City’s Harbor” taken from the Wanamaker file in the vertical files of the Buffalo Bill Museum, Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming.

Newspaper article, “Statue of Indian for City’s Harbor.”

4. MS6 William F. Cody Collection, Series IX, Box 31, McCracken Research Library, Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming.

5. MS6 Box 31, McCracken Research Library, Cody, Wyoming.

6. Appendix, Barsh, Russel Lawrence, “An American Heart of Darkness: The 1913 Expedition for American Indian Citizenship,” Great Plains Quarterly, Vol. 13(2) 1993), 91–115.

7. Barsh, 110.

8. Barsh, 107–108.

Post 173

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.