William Henry Jackson’s Albertype prints – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Summer 2016

Sharing Yellowstone: Lost & Found—William Henry Jackson’s Albertype prints

By Matthew E. Hermes, PhD

Resident Fellow (2015–2016)

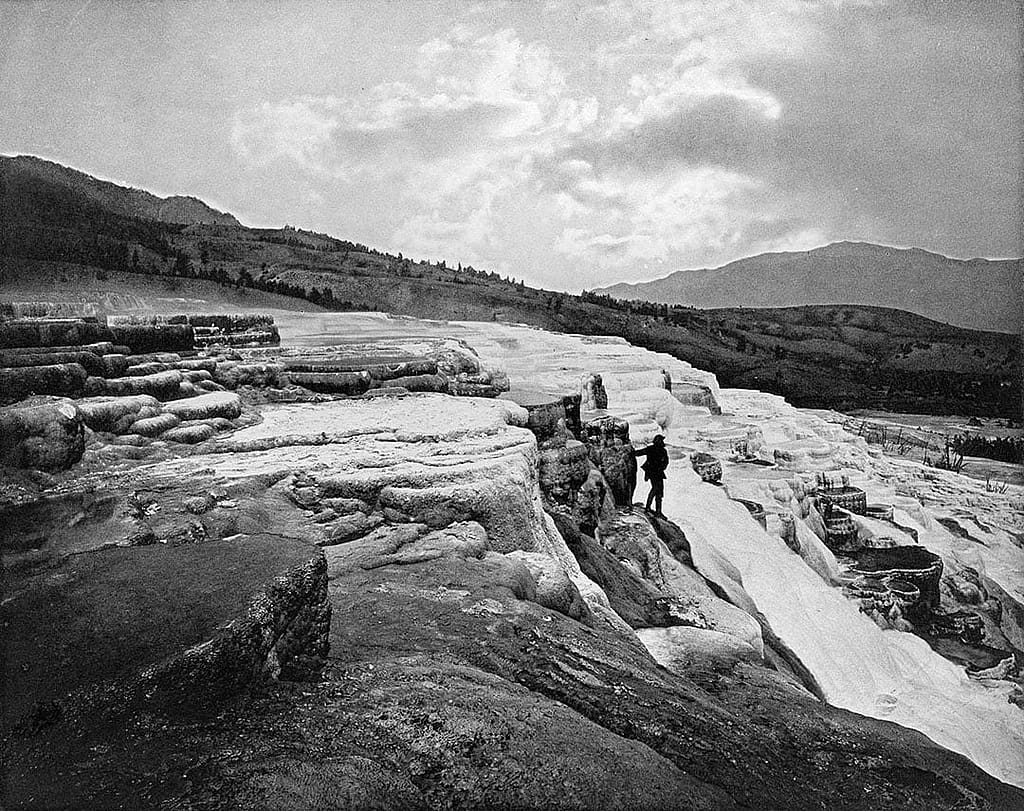

Last December [2015], we gathered in the McCracken Research Library at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West where we opened a bound volume of seventy-six images—prints of William Henry Jackson’s photographs taken as he explored Yellowstone in 1871. He traveled with Ferdinand V. Hayden’s U.S. Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories. Edward Bierstadt—brother of renowned artist Albert Bierstadt—had printed the images in New York in 1874 using his new photomechanical process called Albertypes. They are beautiful, with tonal qualities that make them indistinguishable from Jackson’s original albumen prints.

There in the McCracken, we held in our hands a new discovery: the sole, essentially complete survivor of Hayden’s initiative to share his new National Park with America. With the Albertype process, he dreamt of widely distributing the superb Jackson prints that confirmed the wonders of the place he had so carefully surveyed.

While that sharing never happened, we can see these images today, 140 years after they were printed.

How could it happen that the beautiful and promising Albertypes were not shared with the American public? Here is the story.

Exploration in the 1800s

It is the Gilded Age—fall 1871. The Civil War is behind us. The Central Pacific has punched through the Sierra Nevada—four days by rail, now, from Omaha to San Francisco. John Wesley Powell was said to have made it through the canyons of the Colorado safely.

In fact, explorers all over the globe were making history: Livingston was missing in Africa, and James Gordon Bennett had dispatched Stanley to find him. The North Pole? Unexplored, but not for the trying. The Navy’s expedition ship Polaris was presumed sunk near Greenland. August Petermann, Germany’s precise mapmaker, postulated a warm, navigable Arctic. His influence extended widely, primarily because his map work was so elegant. A captain named Octave Pavy was about to depart from San Francisco to test this hypothesis. The Antarctic? Don’t ask!

The northwest corner of the Wyoming Territory was puzzling, too. Despite lectures by N.P. Langford and Lt. Gustavus Doane, who together had explored the Yellowstone Valley in 1870, the New York Times was skeptical, insisting, “The official narrative of the Hayden expedition must be needful before we can altogether accept stories of wonder hardly short of fairy tales in the wonders they describe.” That means, the Times was needful of additional information!

Well, Hayden soon authenticated the old trappers’ tales and the Langford party’s stories. On his journey, he was accompanied by his photographer William Henry Jackson and by Thomas Moran, an artist. In the Yellowstone Valley, Hayden wrote about the geysers and falls, pulsing steam and bubbling pools. He showed that Langford had not exaggerated, but in fact had underestimated the unique features of this living, volcanic caldera. At the same time, Moran painted the Yellowstone vistas, and William Henry Jackson captured the same views in photographs. He and his mule-borne studio had been with the Survey from its start in Ogden, Utah Territory, to the end three months later.

Going public with Yellowstone

Hayden’s reports led directly to the establishment of Yellowstone as our first National Park. Knowing he would need some evidence to convince others of Yellowstone’s value, Hayden brought back hundreds of Jackson’s glass plate negatives, plus scientific detail of the unique geology, the flora and fauna, and Thomas Moran’s rich watercolors of the shining pools and dense forests. Endorsing the Northern Pacific Railroad’s Jay Cooke’s interest in Yellowstone as a national set-aside, a park, Hayden went public. He buttonholed congressmen, pestered editors, set Jackson to work developing pictures, distributed the images, and ultimately shaped the legislation.

Congressmen gathered, peering over each other’s shoulders, to see Jackson’s contact prints, developed one at a time from his fragile 8 x 10-inch glass negatives. The photographs alone didn’t sell the Yellowstone idea, but combined with Hayden’s passion, his scientific data, and Thomas Moran’s fabulous landscapes, the photos completed a powerful and persuasive package. In just four months, on March 1, 1872, President Grant signed the bill creating the nation’s first national park out of “a tract of land fifty five by sixty five miles” at the Yellowstone.

Now, what? This far-off, virtually unreachable, mysterious park—home to deer, elk, bison, coyotes, wolves, and giant grizzlies; extraordinary landscapes; gurgling mud pots; spectacular water spouts called geysers—this park, a Gilded Age unfunded mandate, had been established as a “pleasure ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people.” An unpaid superintendent was appointed; he set foot on the land just three times within the next five years. Could this kind of park flourish? Hayden realized that Yellowstone needed to be publicized for it to attract visitors.

Selling Yellowstone

As we have seen, Hayden was a bit of a salesman as well as a detailed observer. His documentation of Yellowstone did double duty as publicity—first as official Survey reports, and, even more quickly, as stories presented in the mass media of the day. Hayden wrote a series of articles for the Philadelphia Inquirer and contributed three submissions to the new Scribner’s Monthly. His promotion of Yellowstone had three objectives: expressing his real interest in dramatizing his findings to encourage tourism; enhancing the park’s value to the business interests for whom a successful park would mean profits; and ensuring continued funding for his annual surveys.

Hayden was interested in using the Jackson photographs to share and promote Yellowstone to America. He knew, though, that the technology of 1872 limited their distribution. They could not be reproduced in magazines or books since the technology just was not available. To print just one photo, the image had to be copied to a woodcut or other hand-drawn replica, and a print was made from the replica. The resulting prints, not really photographs at all, would always diminish the thrillingly authentic images of the original photos.

Enter Edward Bierstadt, New York photographer and engraver—brother of the artist Albert Bierstadt—who had purchased rights to a German prototype process of photomechanical reproduction called Albertype. By this method, a photosensitized image created from a glass negative could be repetitively inked, and beautiful images printed from the Albertype plates for inclusion in the mass media.

Bierstadt was contracted to prepare Albertype proofs for the Survey from Jackson’s Yellowstone negatives. Impatient at the prospect of finally having a method for printing multiple copies, Hayden wrote in 1873 that an upcoming special report, “will contain about one-hundred illustrations, printed by the Albertype process from photographic negatives taken by Mr. Jackson.”

He spoke too soon.

Great idea gets burned

Edward Bierstadt’s history of careless manipulation of photographic coatings and solvents caught up with him, and ruined any chance for a printed photographic publication. Two years earlier, on February 8, 1871, the Times had reported the graphic details of a fire following an explosion that sounded “like the discharge of a fifteen-inch gun”; the fire had been “caused by the ignition of a match in the atmosphere highly charged with combustible gas,” at Bierstadt’s 10th Street studio in New York. To whom might Hayden and Jackson have turned had they known about the 1871 fire? We cannot know that, of course. They had faith in Bierstadt, and every reason to expect the commissioned outcome.

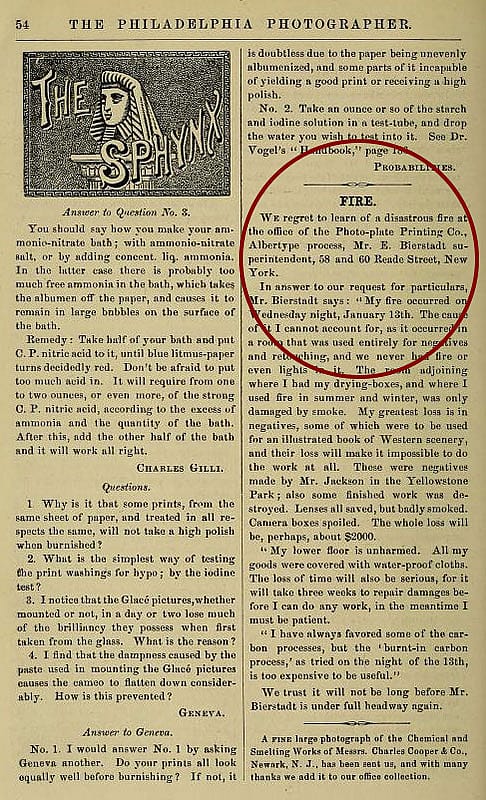

There was a second fire, this one just after Bierstadt had made only a few proof sets of Jackson’s glass plate negatives. Subscribers to the February 1875 Philadelphia Photographer read what had happened a few weeks before: “We regret to learn of a disastrous fire at the office of the Photo-plate Printing Co. Albertype process, Mr. E. Bierstadt superintendent, 58 and 60 Reade Street, New York.”

Bierstadt wrote its editors:

My fire occurred on Wednesday night, January 13th. The cause of it I cannot account for, as it occurred in a room that was used entirely for negatives and retouching, and we never had fire or even lights in it…My greatest loss is in negatives, some of which were to be used in a book of Western scenery and their loss will make it impossible to do the work at all. These were negatives made by Mr. Jackson in the Yellowstone Park. Also some finished work was destroyed.

Hayden was caught completely off guard. He had carelessly reported to the Secretary of the Interior on July 1, 1874, that, “52 plates of scenery prepared by the Albertype process from the photographs of the survey,” along with an additional three dozen images of the Hot Springs area had already been published. None of this had actually occurred. Hayden’s plan for publicity through photomechanical reproduction of the images was thwarted; it was never to be revived.

Jackson’s reaction to the fire is unrecorded. He wrote five decades later, “It may be that some of the proofs were saved, bound, and distributed, but I have no recollection of ever having seen a complete work of the kind.”

Yellowstone Albertypes resurface

It seems that more Albertypes survived than we originally knew. Over the years, partial collections of surviving Jackson Albertypes have surfaced: the Clark Art Museum in Williamstown, Massachusetts, holds a total of fifty-six prints; the Denver Public Library has a few more than thirty; and a handful are at the Library of Congress and elsewhere. In summer 2015, Dr. Robert Enteen, a retired journalist with a passion for taking and collecting photographs, purchased an interesting volume that contained seventy-six meticulously bound prints, all tipped into the binding and protected by separation leaves. The frame of each print identifies it as being a William Henry Jackson image printed by Edward Bierstadt via the Albertype process.

The Enteen prints present an essentially complete pictorial record of the Hayden 1871 survey. They are beautifully preserved and demonstrate the remarkable ability of the Albertype process to present the art, composition, and content of the early glass plate photographs. Each of the prints can be correlated with Jackson’s published list of more than one-hundred-fifty 8 x 10-inch photographs captured on the Survey. Notably, in excess of a dozen of the Enteen prints are unique and do not appear in any other known surviving Jackson Albertype collection.

There are two series of prints. The first, numbered I to LII, are chronological photographs of the Survey’s travels. There are actually fifty-five separate images, not fifty-two as Hayden indicated. Four of the images are double numbered—an error consistent with these prints as proofs and unedited. Unfortunately, one print of the series is missing, a photograph of Tower Falls (XXV, identified because this image does appear in the Clark collection).

The second series of twenty-one was captured during three extraordinary days when the Hayden Survey Party documented the Mammoth Hot Springs.

The “what ifs”

The Jackson Albertypes, had they been used as originally intended, would have been the first effort to promote Yellowstone by photographs. We like to think they would have been broadly popular, the first “coffee table” book perhaps. Albertypes were cumbersome and expensive to produce, but we can speculate that media success would have led to refinement and perfection of this reproduction method. The beautifully rendered images would have catalyzed interest in Yellowstone and led to earlier attention to Yellowstone’s development as the pleasure ground it has become.

![W.H. Jackson's camera brought the depth and contour of the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, a scene unknown to the American public. Jackson wrote, "the Grand Canyon presents a more enchanting and bewildering variety of forms and colors than human artists ever conceived." But even Jackson realized that, "the great picture of the 1871 survey was no picture but a painting by (Thomas) Moran of Yellowstone Falls," capturing, "the color and the atmosphere of spectacular nature." WHJ-A.035. Inset: Thomas Moran (1837-1926). "The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone," 1893-1901. Oil on canvas. On loan at Center of the West in 2009 from Smithsonian American Art Museum; lent by the Department of the Interior Museum. Gift of George D. Pratt [1928.7.1] L.319.2009.1](https://centerofthewest.org/cdn-cgi/image/width=1024,height=810,fit=crop,quality=80,scq=60,gravity=auto,sharpen=1,metadata=none,format=auto,onerror=redirect/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/PW179_WHJ-A_MoranGCY.jpg)

Alas, time marches on. By 1881, commercial halftone processes began to dominate photomechanical reproduction anyway, leaving Albertypes and similar processes to the limited attention of photographers and artists, historians, and, happily, museums.

Dr. Matthew E. Hermes is Research Associate Professor, Department of Bioengineering, Clemson University, Clemson, South Carolina. His collection of western survey documentation is the foundation of his studies of the three western scientist-explorers: F.V. Hayden, J.W. Powell, and Clarence King. He is a 2015–2016 Resident Fellow at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West.

Hermes thanks Mary Robinson, Housel Director of the McCracken Research Library for her enthusiastic support. He offers special thanks to Mack Frost for digitizing the images and determining the locations of Jackson’s camera for so many of the photographs.

Post 179

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.