Pards with Wild Bill and Texas Jack – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Winter 2003

Pards with Wild Bill and Texas Jack

By Thadd Turner

Guest Author

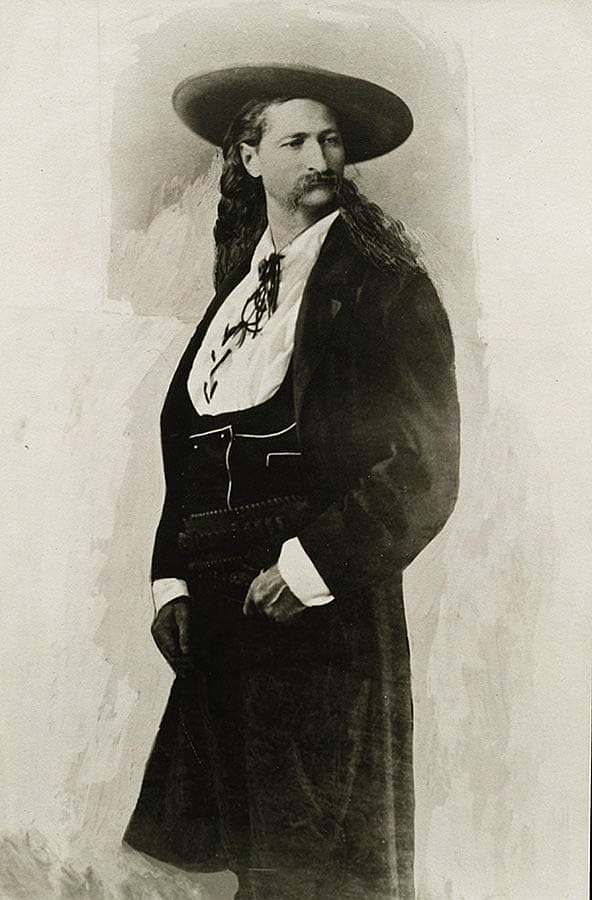

Over the years, Buffalo Bill Cody created many long-lasting friendships and relationships with the well-known and popular characters of his times. Frontiersmen, military leaders, politicians, and even the kings and queens of major European countries could be counted as personal acquaintances on the Christmas list of the legendary showman and plainsman. There were none more popular during the country’s rapid expansion than two of America’s then best-known frontier scouts and dime novel heroes—James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok, the famous lawman and pistoleer, and John B. “Texas Jack” Omohundro, the former Confederate Army scout and Texas cattle drover.

According to the legendary Hickok biographer, Joseph G. Rosa, a young Will Cody probably first met the future lawman and gunfighter sometime in the late summer of 1856 in Leavenworth, Kansas. Hickok had recently relocated there from Illinois, accompanied by his older brother Lorenzo. Wild Bill worked various jobs around the area and at some point was befriended by Isaac and Mary Cody, parents of the then ten-year-old Will. Isaac died soon after in 1857, possibly from lingering wounds sustained from a stabbing at a Free State rally.

Buffalo Bill later wrote in his memoirs that he first met Wild Bill when Hickok saved him from a serious beating by an irate teamster while they were all working for a freighting company. Cody had recently been hired as an “extra”, the term generally used at that time for a young boy too small to drive the teams or load freight, but who was able to perform various camp duties for the crew as an extra hand. When the teamster chose to pick on Cody, Hickok intervened. It’s not certain if this event actually happened, but the two men did form a colorful long-term friendship that by Cody’s own account included a stint with the Pony Express in 1860, Cody offering his talents as an express rider, and Wild Bill working as a teamster and stagecoach driver for the company.

Both Cody and Hickok joined the Union Army in the Civil War. Hickok served as a scout and spy along the Missouri and Kansas borders for almost four years with General John Sanborn and elements of the “buckskin” scouts. Nine years younger, Cody enlisted later in the war and by 1864 was an infantry soldier for a volunteer regiment. Despite stories to the contrary, it is doubtful that they saw one another until after the war’s end in April of 1865. When the terrible fighting finally stopped between American brothers and cousins, both men returned to the open plains and sought employment as civilian scouts for the U.S. military. Hickok served briefly under Lieutenant Colonel George A. Custer in Kansas, while Cody would eventually be assigned to the Fifth Cavalry at Fort McPherson, Nebraska. Cody was later designated chief of scouts for the same troop in June of 1876, just prior to Custer’s defeat at the Little Big Horn in Montana.

A new character soon entered the picture. In the late summer of 1869, Virginian and former Confederate scout John B. Omohundro arrived at Fort Hays, Kansas. He had only recently earned the sobriquet “Texas Jack” driving wild Texas longhorn cattle to the explosive railhead towns in Kansas. There, Texas Jack was introduced to Wild Bill Hickok by another popular Custer scout, Moses E. “California Joe” Milner. By that time, Hickok was serving as the acting Sheriff of Ellis County in nearby Hays City. Texas Jack was well over six feet tall and, like the other two scouts, cut a striking figure. Little is known of the nature of the two men’s friendship during this period, but historians assume that both men may have crossed paths on a number of different occasions over the next four years while they were employed on the frontier.

Soon after meeting Wild Bill, Texas Jack made his way to Cotton Springs, Nebraska, a tiny station and trading post on the very busy Union Pacific railroad that followed the mighty Platte River west. Nearby, Fort McPherson sat alongside the convergence of the Oregon and Overland Express Trails. Upriver, the growing community of North Platte stood poised to become a vital center of trade and commerce that even later would become the birthplace of Buffalo Bill’s outdoor Wild West show. Arriving at Cotton Springs, Texas Jack soon met Cody at the fort. By now, Cody had earned the catchy moniker that would stick with him the rest of his life by hunting buffalo for the Kansas Pacific Railroad.

Both Buffalo Bill and Texas Jack were born in 1846, and that was the least of what they had in common. Like Cody, Jack left home as a teenager, but to work the cattle ranches of Texas prior the outbreak of the Civil War hostilities. He joined his Southern countrymen in 1864 in the battle against the Northern invaders before the war’s end, despite his tender age. Some historians hold that it might have been Texas Jack who put the last dispatches in the hand of the popular Confederate cavalry officer, Major General J.E.B. Stuart, at the battle of Yellow Tavern, Virginia, on May 11, 1864, only moments before Stuart was mortally wounded.

Cody was instrumental in getting Omohundro hired on as a “trail guide and scout” with the Fifth cavalry at Fort McPherson. Soon the two became fast friends and were sharing many frontier duties and campaign experiences in the field. Late in 1871, the Fifth Cavalry was reassigned to Arizona Territory, but the two scouts stayed on at the fort at the request of General Sheridan. By this time, Buffalo Bill had appeared in dime novel stories about the Civil War and America’s wild frontier.

The Grand Duke Alexis of Russia came to America to hunt buffalo in January 1872. Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer and the United States Army hosted this “international” big game hunt, and they wanted only the best trail guides available. Buffalo Bill and Texas Jack were assigned the chief scouting duties. The hunt was a roaring success promoted by the national press, which only made the two scouting pards more popular with the hero-seeking public back East.

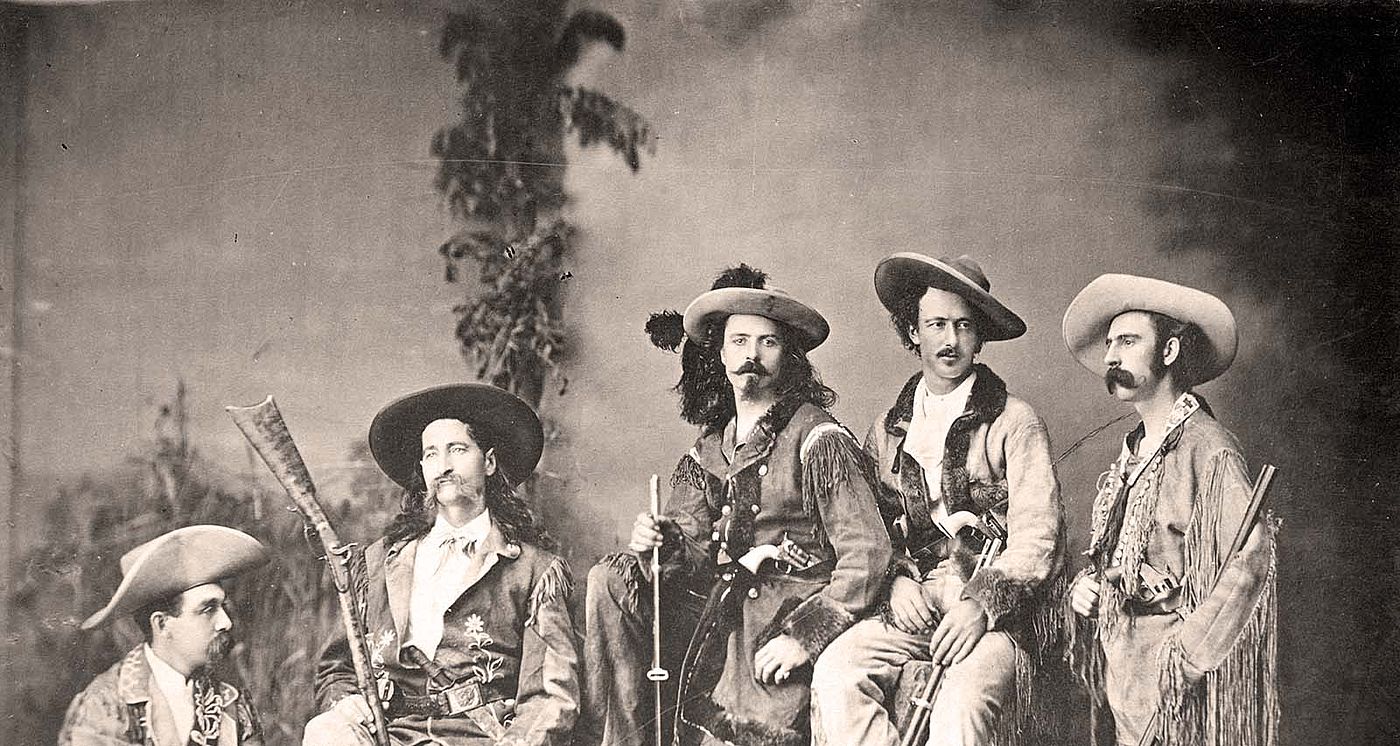

In December of that remarkable year, dime novelist Ned Buntline convinced Buffalo Bill and Texas Jack to come east for the winter and join him in Chicago to act in a stage play he was putting together about their adventures. The fledgling actors were confused as to what their new roles might be but on December 16, only four days after arriving from the wild frontier, the play Scouts of the Prairie opened to a packed house with the inexperienced duo as the leads. The crowd didn’t seem to care that neither scout could act. They were real frontiersmen, and that’s what everyone had come to see.

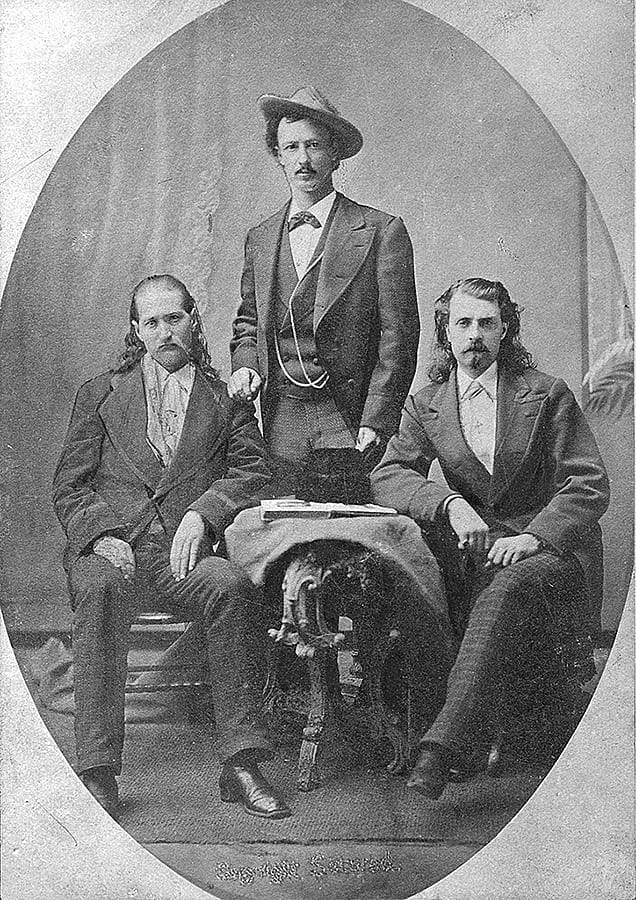

The scouts’ first dramatic season was a success and their acting talent improved. In 1873, the pair went out on their own to produce Scouts of the Plains, and invited Wild Bill to join them on stage under the troupe’s new banner Cody’s Combination. Now the American public had three of the most famous frontiersmen together on one stage. The show played to full houses everywhere along the East coast. Buffalo Bill and Texas Jack had become comfortable on the stage and liked the attention and good wages. Hickok, on the other hand, never took well to the bright lights and crowds, sometimes accusing the other scouts of “play acting” and of degrading themselves for profit. Because of his sincere friendship with Cody and Omohundro, Wild Bill tried to stick it out until the end of the first season but by March of 1874 he had had enough. Homesick for the simplicity of the open plains, he announced that he was leaving the show. In an effort to show they held no hard feelings and appreciated his genuine support, Cody and Omohundro presented their fearless friend with a fine pair of nickel-plated revolvers before Wild Bill left the troupe.

Buffalo Bill and Texas Jack continued with the stage show for two more years before they decided to go their separate ways. For his part, Omohundro married the leading lady, the famous Italian ballerina Giuseppina Morlacchi, and together they developed their own stage troupe. After the unexpected death of his beloved son Kit Carson Cody, Buffalo Bill left the stage and returned to the frontier as chief of scouts for the newly returned Fifth Cavalry. Texas Jack also returned to the West as a newspaper correspondent for The New York Herald.

Ironically, Wild Bill and a small wagon party started for the gold rush in the Black Hills the same week that Custer and his 7th Cavalry met their end at the Little Big Horn. Out on the rolling plains, just south of the new gold fields that lay in the Sioux Indian Reservation, a wild looking vaquero encountered Hickok and the wagon party. It was Buffalo Bill dressed in one of his fancy stage outfits, and he delivered the shocking news of Custer’s death to Wild Bill, a former scout for the ill-fated Lieutenant Colonel. This chance meeting was the last between the two long-time friends. Less than five weeks later on August 2, while gambling and drinking on a warm and lazy afternoon, Hickok was shot in the back of the head and killed by Jack McCall in the No. 10 Saloon in Deadwood, in the South Dakota Black Hills. After the tumultuous summer of 1876, Buffalo Bill returned to the stage for good.

Buffalo Bill outlived both of his longtime pards but never forgot them. Just one year after Hickok’s death, it was announced in the local Deadwood papers that Buffalo Bill had helped pay for a new fence to be erected around Wild Bill’s gravesite to protect the site from trophy seekers and grave robbers. In June of 1880, only three weeks shy of his 34th birthday, Texas Jack contracted pneumonia in Leadville, Colorado where he was performing with his wife and their troupe. Texas Jack’s illness worsened and he died unexpectedly on June 28, 1880, and was laid to rest in the local cemetery with a simple wood headstone and brief inscription.

Twenty-eight years later on September 5, 1908, Buffalo Bill paid tribute to Texas Jack by visiting his old friend’s gravesite and erecting a new marble monument to honor his former companion. On a sunny day in Leadville’s Evergreen Cemetery, the old frontiersman read a small tribute to his scouting pard: “Texas Jack was an old friend of mine, and a good one…. I learned to know him and respect his bravery and ability. He was whole souled, brave, and a good-hearted man.” A local band played a popular stage song from the time, and the ceremony concluded, a fitting tribute to an eternal friendship of trust and enduring loyalty.

Thadd Turner, author and screenwriter, is a member of the Western Writers of America and wrote the non-fiction book, Wild Bill Hickok: Deadwood City—End of Trail, 2001, Old West Alive! Publishing. A former contributing editor for True West magazine, he has been published in Wild West magazine, Deadwood magazine, and NOLA.

Post 194

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.