The Yanks Are Coming: The Great War and Winchester Repeating Arms

The eleventh hour, of the eleventh day, of the eleventh month, for a century now we have worn poppies, lighted lanterns, and recited such solemn lyrics as Flanders’s Field, all honoring the sacred moment when the Great War ended. This November, the Peace Bells on the 11th hour of the 11th day mark the end of the years long commemorations of World War I, but the sacrifice will be remembered.

America’s involvement in the war was short, but much changed for this still fledgling nation from April 6, 1917 to November of 1918. In 1916, President Woodrow Wilson ran on (and won) a promise not to involve the United States in the war raging in Europe and Great Britain. By April of 1917, with Germany’s continued U-boat attacks in the Atlantic, disregarding neutrality of the seas, President Wilson petitioned Congress for a declaration of war and on the sixth day of heated debate it was granted.

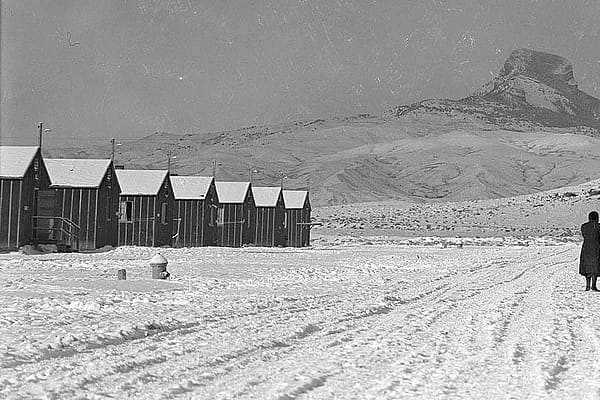

Millions of young men from around the country were drafted or volunteered and traveled from small towns and large cities to recruit training centers on the East and West Coast; none quite sure what they would face in the fields of Europe. Among these was K Company out of Wyoming made up of men from Cody, Burlington, Meeteetse, and Greybull.

World War I changed not only the face of war, but also challenged and advanced a still young country. Women entered the workforce filling in at factory jobs as the men were called up to serve. Also, for the first time in American history, women could officially join the military. The Marine Corps opened its ranks to women, and the first300 lined up and joined the Marine Corps Reserves. Though these positions would be clerical, these original recruits opened the door for military occupational specialties throughout the services for women. The Coast Guard, too, opened a few positions to women, while the Navy had already enlisted “The Sacred Twenty” nurses in 1908. However, by the end of the war, twenty would be 1,386. In France, 223 women (known as the “Hello Girls”) served as long-distance switchboard operators for the U.S. Army Signal Corps.

From the weapons used; poison gases, machine guns, tanks, submarines, airplanes, etc., to the methods of fighting this conflict ushered in a new age of warfare.

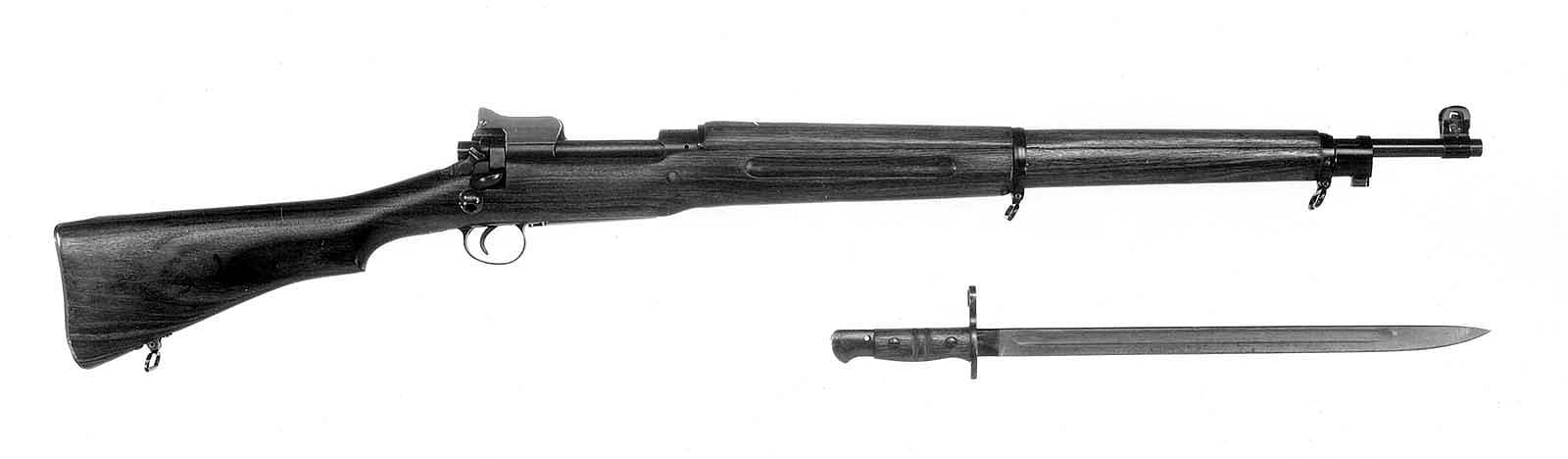

It is not solely the military galvanized when men and women are deployed to war. The Homefront must answer the call for supplies such as: textiles, food, machinery, and of course firearms. Winchester Repeating Arms Company was one of those enterprises in the bulls-eye of wartime production. Winchester had already been supplying Allied Powers with a high volume of armaments since 1914 including a quarter million Enfield Pattern Number 14 (P14s) arming British servicemen, and 300,000 Model 1895 lever-actions for the army of Czar Nicholas II.

When the United States entered the War, Springfield lacked the ability to meet the demand of the standard M1903 rifles. The government turned to civilian arms manufacturers to bridge the gap, and Winchester had to ramp up production to meet the massive demand of millions of Doughboys deploying to the trenches of France and Germany. At the height of wartime production Winchester employed over 17,500 people in a 3 million square feet facility.

Awarded large contracts to equip the Army and Navy, in 1917, Winchester agreed with the government’s requirements and officers were sent by The Ordnance Department to look after the interests of the government and to make sure military specifications were observed. As production increased the government’s presence in New Haven, Connecticut also expanded until there were 17 commissioned officers, 15 enlisted men, and 350 civilian inspectors. The senior officer was Chief Ordnance Inspector, Major H.J. Smith who oversaw the production of rifles with Major F.C. Hubley second in command overseeing ballistics.

While operations were bumpy at first as everyone adjusted to their new roles, the association became one of cooperation. Winchester even petitioned the Army to keep a few of the enlisted men called up for active duty. From accounting, laboratory work, and of course rifles and ballistics the military infiltrated Winchester bringing an even higher standard to the rifles manufactured. One inspector was known to reject material one ten-thousandth of an inch off size.

The need for rifles being the highest priority, Winchester modified the Enfield P14s to accept the American standard 30-06 cartridge and 1917 Enfields (American Enfields) with bayonets were on their way to Europe and into the hands of American servicemen. Over 545,000 of the M1917s were produced for the war effort, making it the most widely used rifle by American soldiers during WWI.

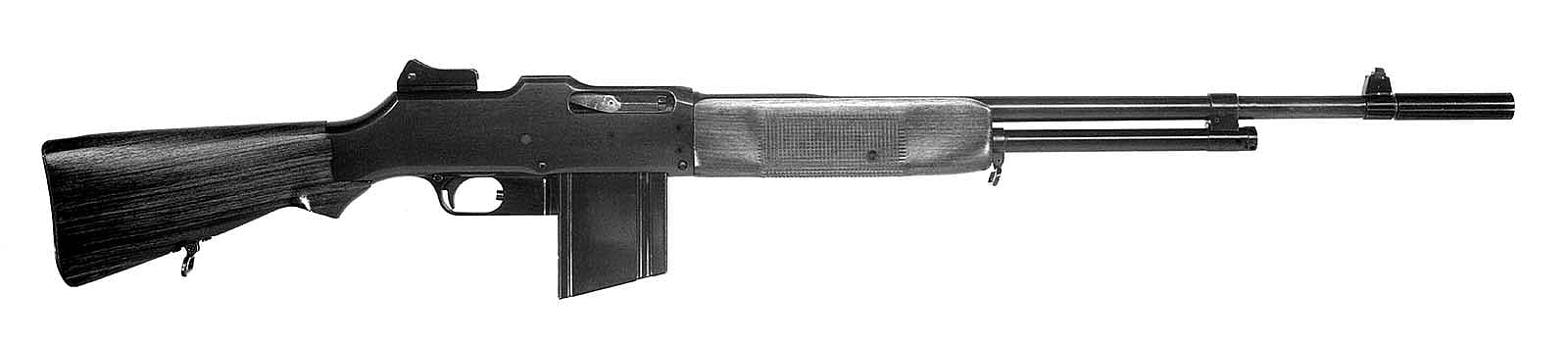

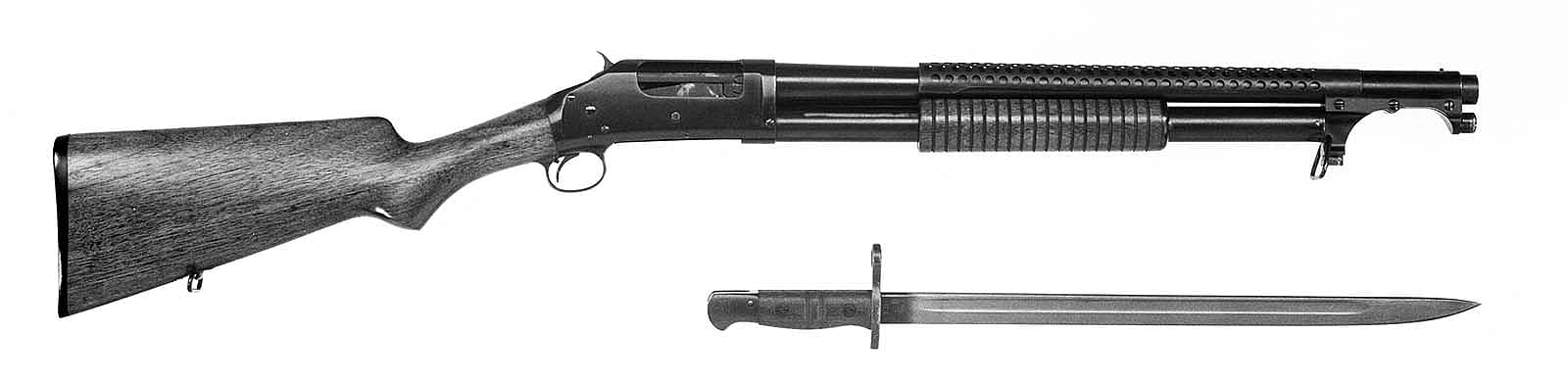

A few other rifles manufactured at Winchester Repeating Arms Company included: 14,000 Model 1918 Browning Automatic Rifles (BARs), .22 cal. Single-shot Musket, modified the Model 1897 pump shotgun into the 97 Riot Gun or “Trench Broom” for close-range conditions, and Sniper rifles (the M1903 with Winchester A5 scope attached). On top of the firearms produced, Winchester churned out millions in cartridges, primers, shot gun shells, etc.

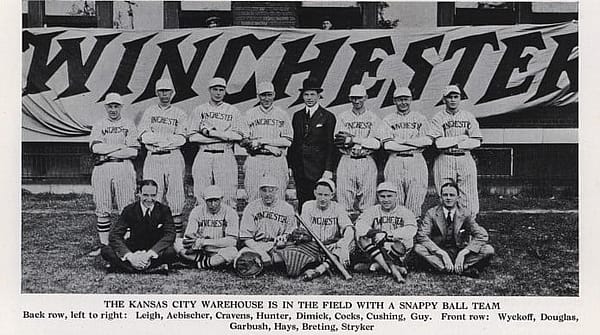

Winchester kept Americans apprised of war efforts, manufacturing news, and the workings of the factory and employees with their Winchester Record often keeping the articles lighthearted and inspirational. Like many companies, Winchester never forgot the human cost behind the war supporting such causes as the Red Cross, War Work Drives, and promoting Bonds on the back of each issue of the Winchester Record. Employees also visited wounded and ill servicemen in hospitals bringing with them well-appreciated chocolate-almond bars.

Bells on November 11, 1918, heralded peace and for many the end of the War to end All Wars. Our young military faced one of its stiffest tests in the muddy, rat infested trenches of France and Germany at places like Verdun, Belleau Wood, Champagne, Vierzy. It’s in this war American Soldiers, Sailors, and Marines exhibited the fighting spirit generations of servicemembers still grasp for as inspiration today, and earned the respect of their allies and enemies.

I have only two men out of my company and 20 out of some other company. We need support, but it is almost suicide to try to get it here as we are swept by machine gun fire and a constant barrage is on us. I have no one on my left and only a few on my right. I will hold. 1stLt. Clifton B. Cates, USMC; in Belleau Wood, 19 July 1918

Millions of the young men sent to war came home, many as changed as the landscape of Europe, returning to their lives in those small towns and big cities as factory workers, teachers, farmers, etc., and attempting to appear as unaffected as possible. For 116,516 American families, victory exacted the highest price and their servicemember returned home in a flag draped coffin or remains forever under a white marker in a foreign cemetery.

After the victory parades and parties, like most of America Winchester adjusted to the post-war. By 1919 the Enfield M1917 was no longer produced as newer prototypes and models were the focus. Prototypes and models that, though they couldn’t have guessed in the euphoria of the dawn of the Roaring Twenties, would be needed against a new threat beginning its rise in Germany, Italy, and Japan.

To all Veterans, on this day and every day, thank you for your service and sacrifice.

Sources:

Letters and memorandums in MS20, the Winchester Repeating Arms Company Archive, ca. 1917-1919. Gift of the Olin Corporation, Winchester Arms Collection

Copies of Winchester Records MS20, the Winchester Repeating Arms Company Archive, ca. 1918. Gift of the Olin Corporation, Winchester Arms Collection

Images courtesy of MS20, the Winchester Repeating Arms Company Archive. Gift of the Olin Corporation, Winchester Arms Collection, MS6 William F. Cody Collection

Written By

Kirsten Arnold

After years in Washington, D.C., Kirsten Arnold escaped D.C. traffic and moved back home to Wyoming where she can enjoy the mountains and open spaces. She holds a Master of Arts in Military Studies, Naval Warfare. In 2018, Kirsten assisted the McCracken Library with the Winchester Manuscript Collections.