The War at Home: Women in the Workforce and World War II in Wyoming

War changes the landscape and people, whether on the frontlines or Homefront. World War II not only tested the millions of American men sent to Europe and the Pacific, but those left to fight the war at home. With the large number of men sent to the front lines (Wyoming alone sent 30,000 men, 10% of its population), this left a gaping hole in the workforce of the country.

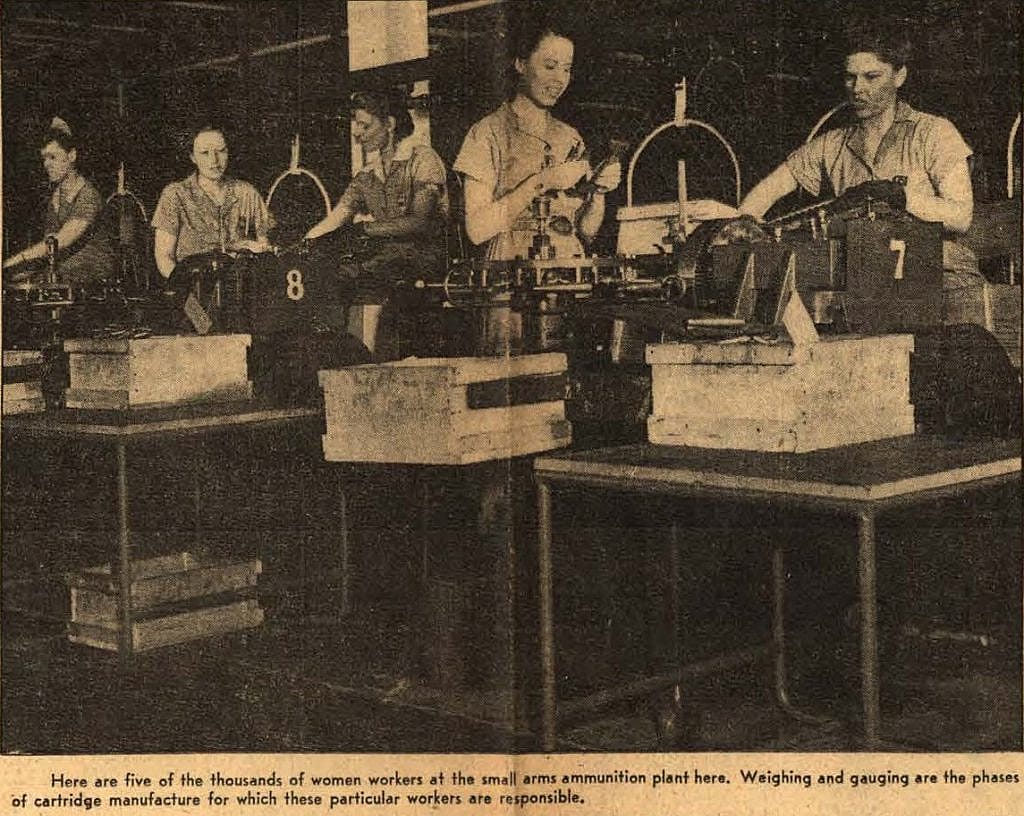

Factories, now responsible for producing airplanes, firearms, ammunitions, food, and other supplies for the troops, employed thousands of women to step in and work the lines. Just like the men who joined the armed services, the women who took the jobs in the factories came from all walks of life. They were farmers, teachers, waitresses, homemakers, bookkeepers, etc., and all understood the importance of their work. “When guns are roaring in defense of their country, the women are handing munitions to the men,” wrote Edna Warren in her 1942 article in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat about the United States Cartridge Company in St. Louis.

Of course, for many it wasn’t solely a patriotic duty but with the hope their work would keep husbands, fathers, brothers, etc. safe. Warren witnessed one young woman kiss a cartridge as she slipped it into her machine and whisper, “here’s one for you, Hitler.”

Brown coveralls were a familiar sight and the women would roll these up to the knees leaving “a bare expanse of legs down to socks and shoes.” Hair nets were part of the uniform as well as a red bandana for wiping the machinery.

The cafeterias at most factories offered good food at reasonable prices for their workers. The lunch hour was a time to relax, visit, and for some young women and men a time to find romance. Colonel Bowlin at United States Cartridge claimed many marriages among workers occurred.

The average pay for women at most factory jobs was $30.00 a week. Many who had worked in other jobs found they enjoyed the jobs at the factories. Whether finding romance, aiding the war effort, finding their place, or all of the above, for many of the women giving up their place on the line once the men returned from war was bittersweet. Where “a woman’s place” was in the United States would be questioned and argued in the years after the war.

For other Americans, they lost their place in the United States and question if they ever had a place at all. On 19 February 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. This order authorized the military to designate “military zones.” This was quickly followed with “Instructions to All Persons of Japanese Ancestry,” issued by General John L. DeWitt on 2 March 1942. These were the instructions telling the Issei (Japanese who had immigrated to the United States) and Nisei (Japanese-Americans born in the United States) where to report with their belongings.

The hastily assembled detention centers were converted from racetracks and fairgrounds. For many of the 120,000 men, women, and children removed from their homes, the removal from their homes meant these houses and businesses were lost to them. Some had friends who took care of the homes and businesses, but the majority did not and left for the centers with only what they could carry.

Forty-six thousand acres at the foot of Heart Mountain in Wyoming was set aside for one of the ten permanent internment camps complete with guard towers and barbed wire. This War Relocation Authority facility existed from August 1942 to September 1945 with close to 14,000 internees passing through the camp. Many internees stayed behind the barbed wire of Heart Mountain the entire three years. At its peak, the population was 10,767.

Heart Mountain consisted of 468 barrack-style buildings sectioned into 20 blocks that served as administration areas and living quarters. The barracks were divided into apartments, some single rooms, and others slightly larger to accommodate families up to six. Each unit was furnished with a stove for heat, a light fixture, and an army cot and two blankets for each person. Each block had a mess hall, unpartitioned toilet and shower facilities and a laundry area.

Internees held a variety of jobs within the camp, doctors, dentists, teachers, etc. The camp also had a garment factory, cabinet shop, sawmill, and silk screen shop. However, the WRA decided Japanese could not be paid more than a private in the Army. So, a Japanese-American doctor made $19 per month while a Caucasian nurse made $150 a month. Japanese-American teachers made $228 a year while their Caucasian counterpart earned $2,000 per year.

In 1943, the camp began agricultural efforts. The first completed the Shoshone Irrigation Project (5,000-foot canal) was the first completed. They cleared thousands of acres of land planting peas, beans, cabbage, carrots, cantaloupe, watermelon, and other fruits and vegetables yielding 1,065 tons of produce its first year. Internees raised cattle, hogs, and chickens for their own consumption.

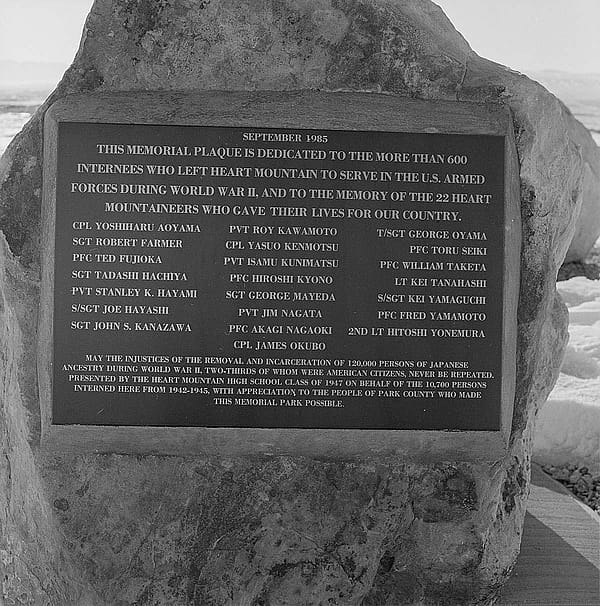

One of the most remarkable parts of the internment camp history was the fact that while they were being interred many young Niesi joined the military and fought for the United States in Europe. More than 800 young men from Heart Mountain served in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, the most decorated unit in U.S. military history for its size and length of service. Two of these soldiers received the Medal of Honor.

In early 1945, internees were allowed to return to the West Coast. Each person was given $25 and a train ticket. The last train of internees left Heart Mountain on November 10, 1945. For many there was nothing to return to on the West Coast and they had to start all over again. Although the land and barracks were sold to former servicemen, today visitors can visit the Heart Mountain Interpretation Center and learn about this dark period in our nation’s history.

In a few cases, the United States Homefront was a part of an individual’s war. Prisoner of War camps were established throughout the western United States. Wyoming had approximately 19 of these camps, interring Italian, German, and Austrian POWs.

Camp Douglas served as the primary camp in Wyoming housing 2,000 Italian and 3,000 German POWs from 1943 to 1946. The camp was comprised of 180 buildings and 500 Army personnel also resided there as guards and administrators of the camp.

Satellite camps were established in towns such as, Dubois, Basin, Deaver, Lovell, Clearmont, etc. Prisoners from these camps were often hired to work on farms, ranches, or in the case of Dubois, as tie-hacks to fill the employment gap for seasons.

The landscape and cowboys inspired three Italian POWs to paint murals on the walls of the officer’s club at Camp Douglas. Like these Italian artists, the majority of the POWs attempted to make the best of the situation, and some came to admire the landscape of Wyoming. A few even returned years after the war to visit, and some cases, make a new life.

However, there were a few issues with pro-Nazi German POWs. These men were restricted in their interactions and were not allowed to leave Camp Douglas for the satellite camps. There were a few escape attempts, but, the landscape and vastness of the state served as the best deterrents for too many such efforts. In November 1945, the Army began the process of sending the POWs home, and by February 1946, Camp Douglas was closed.

In a war as all-encompassing as World War II, no one emerges the same. Soldiers, Sailors, Marines, women, Japanese-Americans, and POWs; all faced a new normal once the ticker tape stopped falling on celebrations of V-E Day and V-J Day. The country itself faced a new normal as it emerged from this war as a world power. New struggles for equality and inclusion would occur. The United States would have to decide what our new place in the world order would mean for our future, and it had to decide quickly because a cold war was getting hot.

Sources:

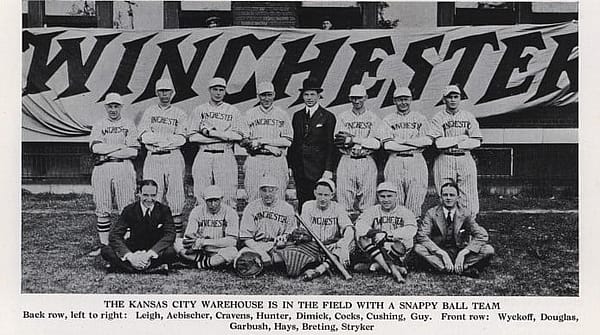

Copies of Winchester Records MS063, the Winchester Repeating Arms Company Archive, Gift of the Olin Corporation, Winchester Arms Collection, Newspaper clipping from, St Louis Globe-Democrat, July 31, 1942, pg. 13. McCracken Research Library, Buffalo Bill Center of the West

Photographs of Heart Mountain courtesy of MS089 Jack Richard Photograph Collection, McCracken Research Library, Buffalo Bill Center of the West

Heart Mountain Interpretive Center, http://heartmountain.org/history.html

Camp Douglas video, Wyoming State Parks, http://wyoparks.state.wy.us/index.php/places-to-go/camp-douglas

Written By

Kirsten Arnold

After years in Washington, D.C., Kirsten Arnold escaped D.C. traffic and moved back home to Wyoming where she can enjoy the mountains and open spaces. She holds a Master of Arts in Military Studies, Naval Warfare. In 2018, Kirsten assisted the McCracken Library with the Winchester Manuscript Collections.