Points West Online: Will James & Me—New Books at the McCracken

Originally published in Points West magazine

Spring 2016

Will James & Me: New Books at the McCracken

By Eric Rossborough

Will James was an author who brought the West to life for a child enamored of the West, Eric Rossborough, and youngsters like him. After processing a special gift of western books to the Center’s McCracken Research Library, including several by James, Rossborough recalls all that spurred his own passion for the Wild West.

Wild about the West.

When I was ten years old, my older sister Julie moved to California. I was very excited by this, because this was the closest anyone in our family had been to the West. California was the West, right? I was obsessed with the West—the Old West mainly, but the new West would do if that was all I could get. Julie stoked my interest by, in one letter, mailing me a little plastic cowboy that I set on my windowsill. The cowboy is gone of course, but a couple months later she sent me something that would have a much more lasting impact.

As someone whose declared career ambition was to be a cowboy, I was hungry for any and all looks at my future digs. What I didn’t realize was that my sister was living in San Diego, which was not exactly the West the way I thought of the West. One woman, the daughter of a neighbor, lived in Tucson, Arizona, and she obliged me by sending pictures of her condominium with its swimming pool. I studied the picture; surely there was a horse just beyond the fence that rounded the unit. Then my sister’s package came.

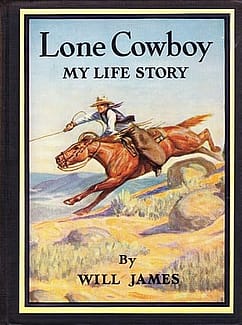

There were two books. One of them, Life of Kit Carson, the Great Western Hunter and Guide, started like this: “As, for their intrepid boldness and stern truthfulness, the exploits and deeds of the old Danish sea-kings, have, since the age of Canute, been justly heralded in story and song.” What? That didn’t go so well—and it certainly didn’t sound anything like a western tale. The other book, Lone Cowboy by Will James, was much different.

Meeting Will James

In this particular volume, James claims to have been born on the grass of Montana, much as if he were a cow or horse himself. After the untimely deaths of his parents—his father being kicked to pieces by a horse—he is raised by a French-Canadian trapper who speaks no English. The book is notable for its complete lack of towns, or even buildings. They live a houseless existence, and after the trapper drowns one morning—at least we think he did, since all Billee, as he is called, ever finds is a dented bucket stuck in the rocks of a creek—young James sets out on his own.

I ate this up. As someone who intended to be a cowboy, I needed to get all the information I could. Of particular interest to me was James’s description of climbing out of his bedroll on a winter’s night to chase cows, and pulling on frozen socks, encrusted with snow. How was I going to be able to do that?

It wasn’t true, of course: I don’t mean the part about the socks, which probably was true, but the part about being born on the grass. Will James, born Ernest Dufault to a family of middle-class hotelkeepers in Quebec, Canada, wanted to be a cowboy too. He ate up western dime novels, attended a performance of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, and was an indifferent student. North woods trappers frequented the family hotel, and listening to their stories may have given James the inspiration for his putative guardian. Dufault family members describe him lying on the floor, churning out drawings of horses and cowboys. At fourteen, accompanied only by a batch of cookies his mother made for him as a parting gift, James headed to Alberta.

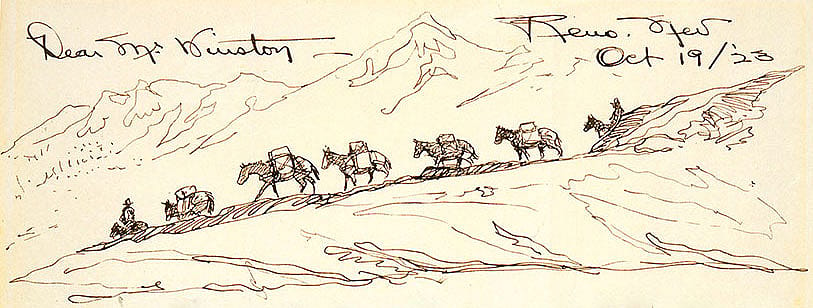

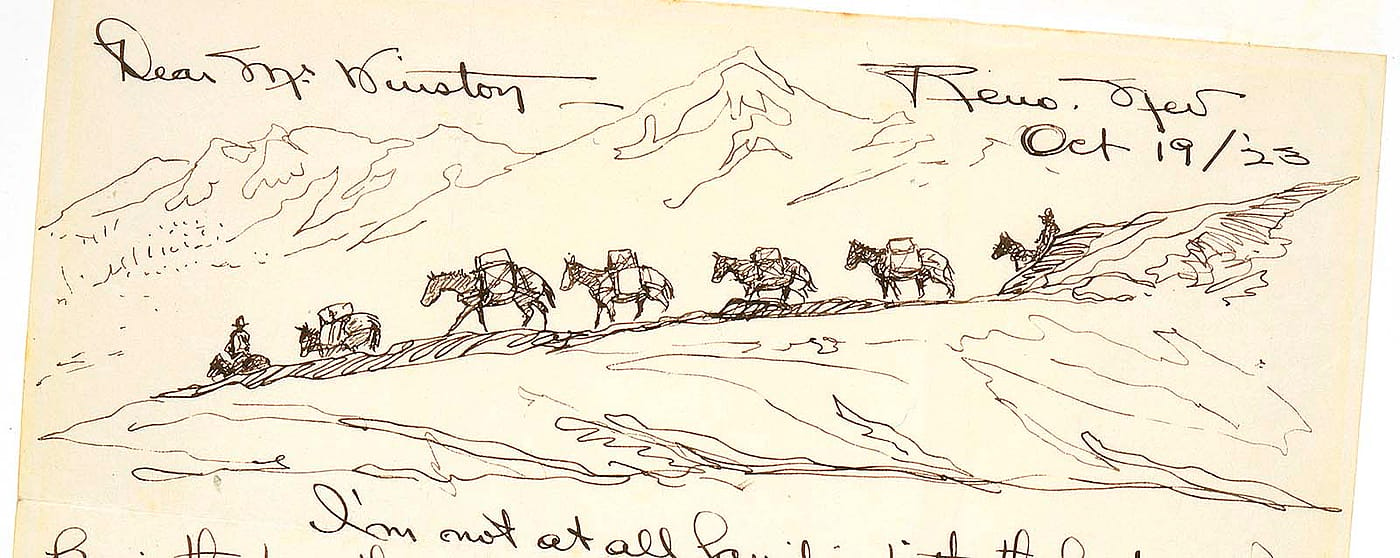

![While incarcerated in Nevada, James impressed his captors with his horse sketches, probably similar to this drawing from an illustrated letter James sent to fellow artist and friend, Charlie Russell, May 30, 1920. (Note James's comment to Russell: "Well sir just got back from a trip in Nevada, had a little business to tend to and also see some of the old boys of course…I did'nt [sic] think I'd be gone quite that long, anyhow I am mighty glad to hear from you…") Gift of William E. Weiss. 79.60.2a/b](https://centerofthewest.org/cdn-cgi/image/width=1024,height=638,fit=crop,quality=80,scq=60,gravity=auto,sharpen=1,metadata=none,format=auto,onerror=redirect/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/PW221_letter-79.60.2.jpg)

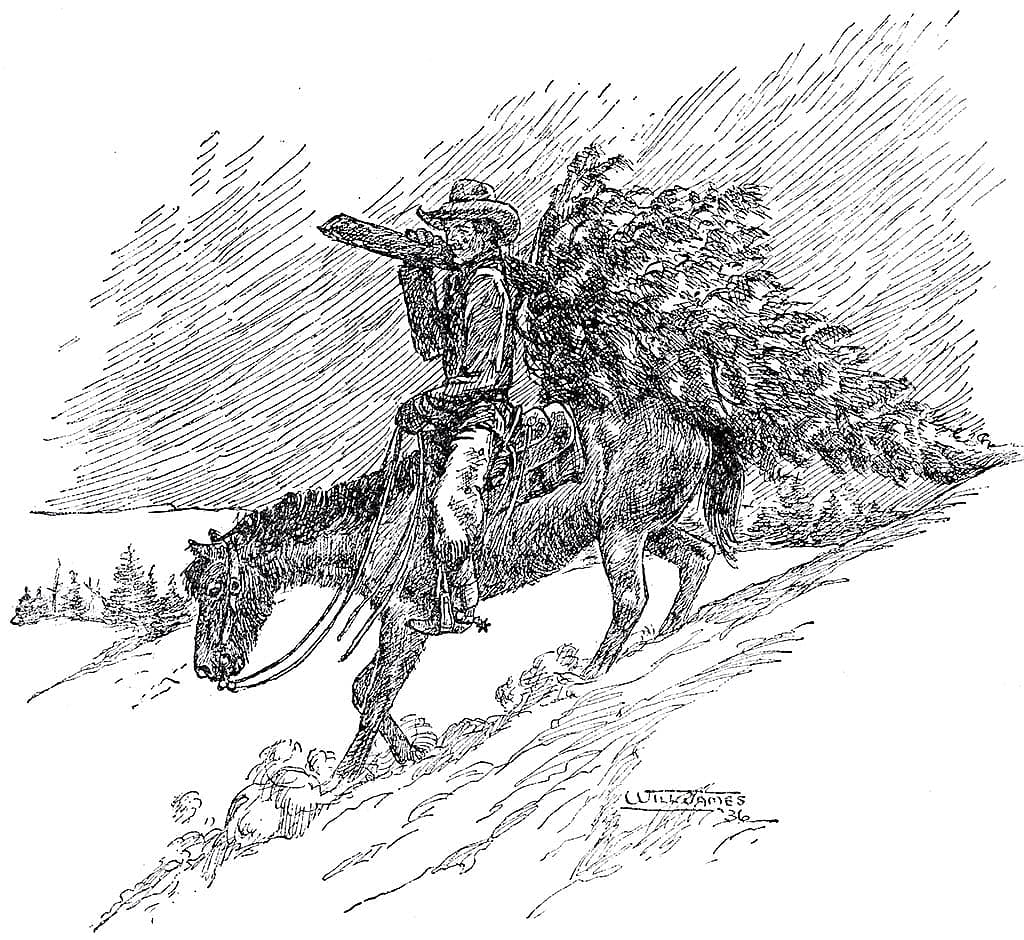

Will James on his own

A photo of James in 1907 shows him with a looped rope, leaning on a saddled horse, still looking a little out of his element. Apparently, the seasoned cowboys hazed him ferociously, but he stuck it out. Early accounts, what few there are, by people who knew him, say James wasn’t much of a rider early on. This changed, though. He did roam all over the West, spending a lot of time in Nevada. Drawings he left behind littered the cow camps he’d frequented. He did time for cattle rustling, chased wild horses, and cowboyed between Canada and Mexico.

This too seems to be true. Unlike many purveyors of Wild West mythology, James actually lived what he wrote for many years. And unlike Charlie Russell, who was by all accounts—including his own—not much of a rider, James rode the rough string, breaking horses for various ranches.

In 1914, authorities arrested James for cattle rustling and sent him to the jail in Ely, Nevada. He ended up spending a year in the state penitentiary where he charmed his captors with drawings of horses. Upon his release, James resumed his itinerant lifestyle. A broken jaw brought him to Los Angeles for medical attention, where he obtained work as a stuntman on silent westerns. The movie studio thought he was handsome and wanted him to act. He said no, and took a train back to Nevada. This went on until a horse named Happy dumped Bill James—as his friends called him—onto some railroad tracks, giving him a concussion and ending his cowboy career for good.

Not a cowboy anymore

From there the story gets less interesting, or at least less peripatetic. Will James recuperated at the home of a friend where he spent his recovery time drawing.

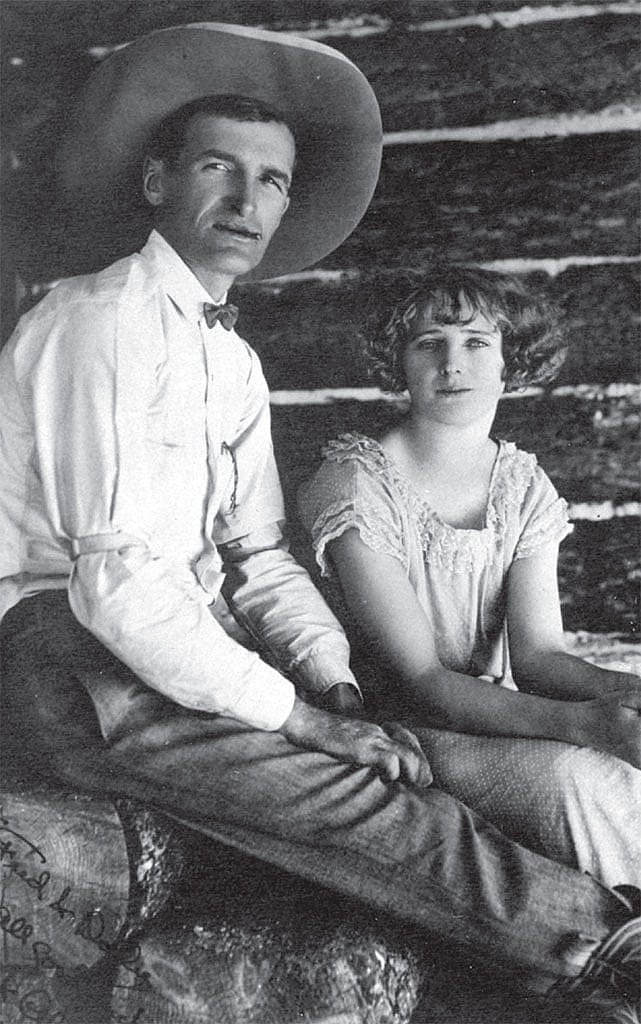

Then, he married Alice Conradt, his friend’s sister, over the objections of her father, who did not want his daughter marrying a shiftless cowboy. Alice recommended he write some stories about bucking horses, “Since that’s all you ever talk about anyway.” Appearances in magazines like Sunset brought him to the attention of uber-editor Maxwell Perkins who shepherded the careers of people like F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway; James was off.

His book Smoky the Cowhorse won the notable Newbery Award, recognition for the year’s most distinguished contribution to American literature for children. Wife Alice was horrified by the rootless existence depicted in Lone Cowboy. Such a man, she thought, maybe never should have married. James turned out to be a somewhat inattentive husband himself, walking the prairie by himself smoking cigarettes. He seemed to live in his own world.

Pressure takes its toll

One day when I was eight years old, I looked in my parents’ TV Guide and saw a listing for a filmed version of Smoky; I sat in the basement eagerly. What was more, the producers had the great idea of having Will James sit at his easel and provide narration. I would get to see my man in person. Picture me leaning forward.

James didn’t look like much. He looked gaunt and didn’t have much to say. Even to my young mind, I figured something was not quite right. Later, I read that this narration plan hadn’t worked out the way the movie makers had expected. James was so drunk that most of his footage ended up on the cutting room floor.

In reality, the pressure of his double life was killing him. After he became famous, he wrote a letter to his family in Quebec. “I had absolutely no idea this was going to happen,” he wrote in French, “and if anyone finds out I am really in for it.” I found this out one afternoon walking the aisles of the Boston Public Library. I was doing research for a college paper on Greek mythology, and I stumbled across Will James, the Gilt Edged Cowboy by Anthony Amaral. I didn’t do any more work that afternoon.

Will James died alone in an apartment in Hollywood, California, at the age of fifty, having driven away his biological and adopted families. His last book was The American Cowboy. While his personal life deteriorated, James never gave up writing; he had big plans for his last book. It was to be an epic of the plains which covered the entire history of the cowboy in North America, through successive generations of horsemen—all named Bill. The last line of the book is, “The cowboy will never die.”

In his declining days, James worked as a Hollywood screenwriter, a maw that chewed up greater talents than his. He spent his days drinking whiskey from a tall glass and telling stories of the open range to his secretary, Bea Masters. In reality, Will James’s years on the plains, from about 1910 to 1919, took place, really, after the open range days. But he has no problem constructing his narratives in a houseless, townless, never-never land that lacks fences or even borders. Masters was rattled at first by James’s large frame and bleary expression, but she came to find him quite sweet. They never actually did any writing. She realized he was lonely and just wanted someone to sit and listen.

Years later, someone told her of his jailbird past. Impossible. When someone showed her documents concerning his stint in the Nevada State Prison for stealing cattle, she insisted, “I don’t care what it says, I still won’t believe it. It must have been another Will James.” To her, he was a fine person at heart, a gentleman, who never once swore before her or even told an off-color joke.

When she saw the handwriting on his parole letters and recognized it as his, she cried and cried.

For me, the cowboy thing didn’t quite work out. Instead of the nineteenth century, I ended up in the twentieth century, where I was born—but I do work in a cowboy library. Here at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West’s McCracken Research Library there are extensive materials on western Americana. I am surrounded by this stuff all day long…My relatives have puzzled over this…

About author Eric Rossborough

Eric Rossborough has been rooting around the West since he took a job at the Center’s McCracken Research Library. He was raised in Massachusetts and comes to the Center by way of Wisconsin, where he worked at a public library, and enjoyed working on prescribed fires and fishing for bass and bluegills. He has a lifelong interest in natural history and the Old West.

Post 221

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.