Buffalo Bill and The Fight to Save Yellowstone’s Wildlife – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Fall 2012

Buffalo Bill and The Fight to Save Yellowstone’s Wildlife

By Jeremy Johnston, PhD, Managing Editor of the Papers of William F. Cody and Curator of the Buffalo Bill Museum

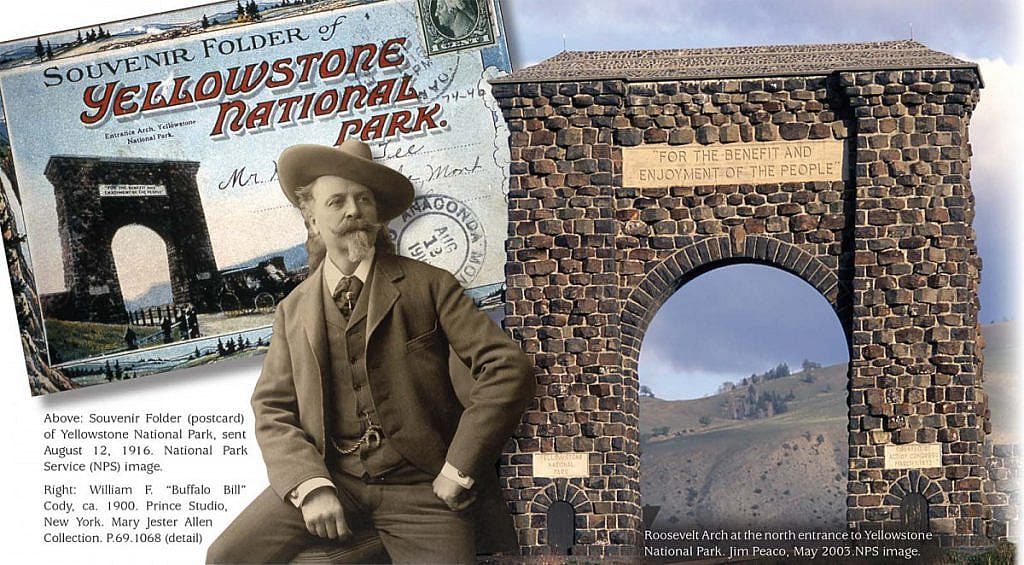

On March 1, 1872, President Ulysses S. Grant signed the bill creating Yellowstone National Park—an event hailed by future generations as a critical step toward the preservation of the American wilderness. The bill clearly stated that the region was to serve as a “public park or pleasuring ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people.” The legislation further stipulated that “…regulations shall provide for the preservation from injury or spoilation of all timber, mineral deposits, natural curiosities, or wonders within the park, and their retention in their natural condition.” To list and enforce these regulations, the Secretary of the Department of the Interior appointed a park superintendent. Unfortunately, Congress did not appropriate any funds for the new superintendent or provide for additional staff to enforce said regulations. Due to this significant limitation, the 1872 legislation did little to protect the natural features of the newly created Yellowstone National Park.

… For the Benefit and Enjoyment of the People …

Without an effective administration overseeing the new park, the initial onslaught of tourists and concessionaires seeking sport and food devastated Yellowstone’s wildlife populations. Market hunters soon discovered Yellowstone provided them one remaining pocket of western wildlife to exploit. Yellowstone’s bison and elk herds provided a source of food for the mining districts of Montana. The park also offered opportunities to provide bison heads to taxidermists who then sold the trophy mounts to various businesses and individuals who wanted to honor this vanishing wildlife species. Members of the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks demanded elk ivories to garnish their jewelry, thus displaying their loyalty to the order. To meet these demands, various market hunters slaughtered Yellowstone wildlife, especially in the winter months when tourists and the few government employees patrolling the park were scarce.

The number of animals killed within the boundaries of Yellowstone, and the cruel methods used by market hunters, marked the park’s first few years as a dark period. The Bottler Brothers, a family residing north of Yellowstone, reportedly killed more than two thousand animals within the Yellowstone region in just one season. Market hunters also devised cruel methods to save on expenses, such as driving elk into snowdrifts to entrap their prey and cut ivories out of the live elk’s mouth with a knife. While this saved ammunition and led to greater profits for the hunter, it led to a grueling and painful death for many elk.

The presence of bison carcasses provided an additional economic opportunity for poisoning scavengers and predators to secure various pelts. Even the fish within the park suffered. Miners from the developing mining community of Cooke City, Montana, (just outside the park’s Northeast Gate) found it easier to secure fish by dynamiting Yellowstone’s lakes. The Yellowstone National Park bill clearly stated the park superintendent’s regulations should prevent “wanton destruction” of fish and wildlife; however, only a handful of concerned citizens decried the actions of these market hunters, and the early park superintendents and their employees either did not care or did not have the resources to end the slaughter.

Nonetheless, a few individuals did protest the destruction of Yellowstone’s natural features and wildlife. In 1875, Captain William Ludlow of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers led a scientific expedition through Yellowstone National Park. With Ludlow’s group was George Bird Grinnell, a naturalist who composed the zoological report of the expedition. Grinnell grew up in Audubon Park, New York, where he was inspired to become a naturalist by John James Audubon’s widow, Lucy. Ignoring his father’s wishes to become a Wall Street broker, Grinnell instead went west to explore its vast wildlife and become a naturalist. As a matter of fact, Grinnell explored the Black Hills with the famed army officer George Armstrong Custer in 1874. (Fortunately, Grinnell declined to join Custer on his military expedition in 1876 that ended with the Battle of the Little Bighorn near present day Hardin, Montana.)

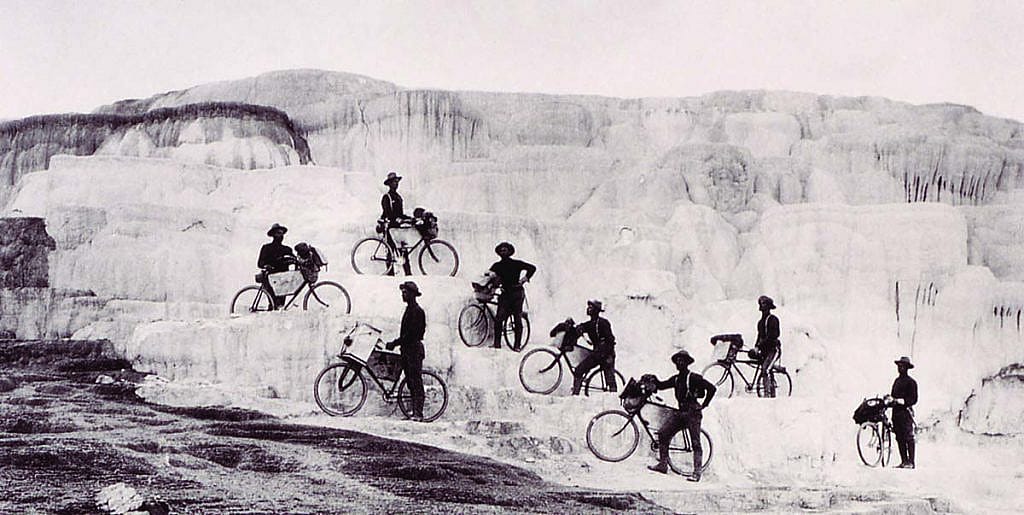

During the Ludlow expedition through Yellowstone, Grinnell learned that due to heavy snows of the previous winter, market hunters slaughtered fifteen hundred to two thousand elk just within a fifteen-mile radius of Mammoth Hot Springs at the northwest corner of the park. Based on Grinnell’s observations of Yellowstone’s wildlife and its destruction, Ludlow wrote the following statement in his report, “… this wholesale and wasteful butchery can have but one effect… the extermination of the animal… from the very region where he has a right to expect protection, and where his frequent inoffensive presence would give the greatest pleasure to the greatest number.”

… This wholesale and wasteful butchery can have but one effect… The extermination of the animal …

To ensure the proper protection of Yellowstone and its wildlife, Ludlow’s report urged Congress to transfer the management of the park to the U.S. War Department so that cavalry troops could police the park, protecting it from devastation and preserving it for future generations. Ludlow concluded his report with the following prophecy, “… the day will come… when this most interesting region, crowded with marvels and adorned with the most superb scenery, will be rendered accessible to all; and then, thronged with visitors from all over the world, it will be what nature and Congress, for once working together in unison, have declared what it should be, a National Park.”

Yellowstone’s wildlife populations were somewhat protected after P.W. Norris became superintendent in 1877. Norris posted a regulation to end market hunting within Yellowstone’s boundaries and secured Yellowstone’s first federal funds to hire a staff to enforce regulations. However, patrolling the park’s 2.2 million acres proved an overwhelming challenge, and the slaughter continued despite Norris’s efforts. He continued his attempt to protect Yellowstone until February 1882 when Patrick Conger replaced him. In his history of Yellowstone National Park, Hiram Chittenden noted that Conger’s “administration was throughout characterized by a weakness and inefficiency which brought the park to the lowest ebb of its fortunes, and drew forth the severe condemnation of visitors and public officials alike.”

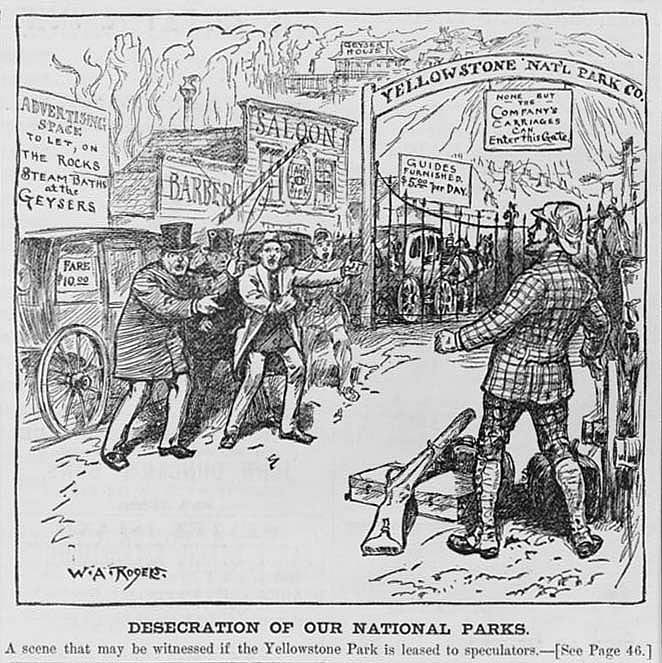

Conger, known to have strong ties to the railroads, assumed his leadership at the same time the Northern Pacific Railroad (NPRR) sought construction of a rail line from Livingston, Montana, to Yellowstone, formed the Yellowstone Park Improvement Company (YPIC) to construct hotels and provide services to tourists who would soon be arriving via the completed rail line to Yellowstone. Assistant Secretary of the Interior Merritt Joslyn promised YPIC a handful of 640-acre leases within Yellowstone, giving YPIC control of more than four thousand acres of federal land, thus granting the concessionaire a complete monopoly of Yellowstone’s most scenic wonders to a subsidiary company of the NPRR. Additionally, the leases provided YPIC the freedom to secure timber resources within the park to construct facilities, as well as permission for professional hunters to kill park wildlife to feed construction crews.

Shortly after an 1882 trip through Yellowstone, General Phillip H. Sheridan publicly voiced his concern for the future of Yellowstone after leaning of YPIC’s efforts to monopolize the tourist trade and exploit Yellowstone’s timber and wildlife resources. Sheridan decried the leasing of the park and echoed Ludlow and Grinnell’s calls for the War Department to take over the administration of Yellowstone. Additionally, Sheridan recommended Congress expand the park’s eastern boundary to the mouth of the Shoshone Canyon, near present-day Cody, Wyoming, to provide additional protected habitat for the park’s dwindling wildlife populations.

George Bird Grinnell, who by this time was the editor of the sporting journal of Forest and Stream, voiced his support for Sheridan’s recommendations. Grinnell argued in the magazine that Yellowstone was a single rock standing to break the negative impacts of western immigration, a place “Where the large game of the West ma be preserved from extermination; here… it may be seen by generations yet unborn.” Influenced by Grinnell’s writings, on January 3, 1883, U.S. Senator George Graham Vest introduced a bill within the Senate to incorporate Sheridan’s recommendations. The public debate over Yellowstone’s future now intensified.

… Sheridan recommended Congress expand the Park’s eastern boundary to the mouth of the Shoshone Canyon …

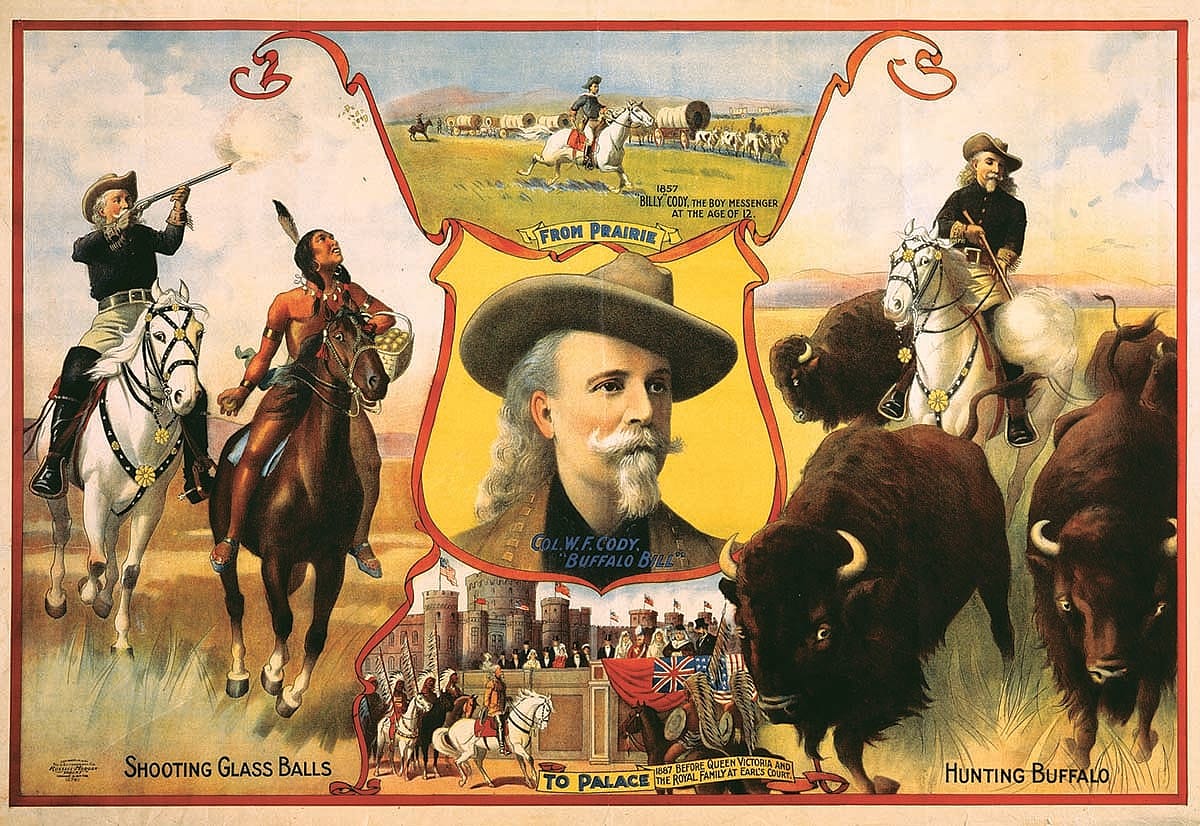

Shortly after Vest introduced his bill, public support came from an individual many would consider an unlikely proponent of wildlife protection in the American West – William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody. During the debate over Yellowstone’s future, the former military scout turned actor wrote a letter to the New York Sun voicing his support for the increased protection of Yellowstone National Park. The flamboyant language used in the letter suggests Cody’s publicist John M. Burke either wrote or assisted Cody in writing the letter. Despite the question of authorship, the letter to the New York Sun brought Cody into the debate over Yellowstone’s future.

Cody earned his moniker “Buffalo Bill” by killing more than four thousand bison to feed the construction crews of the Kansas Pacific Railroad; many historians later concluded his allegiance to the railroads and his career as a market hunter made him a very unlikely individual to support any conservation issues limiting economic development within the American West. The 1883 letter written in Cody’s name reflects his unfamiliarity with Yellowstone’s wildlife conditions. For example, American Indian people long hunted in the Yellowstone region and did not avoid the area because of the geothermal features, contrary to tales told among later tourists.

Cody also ignored the fact that many early visitors and concessionaires had already significantly reduced Yellowstone’s wildlife populations. It is doubtful that Cody visited Yellowstone National Park until the late 1890s, during the time he was overseeing development of the town of Cody, Wyoming, and viewing tourism to Yellowstone as an invaluable economic resource for the developing town named in his honor. The information stated in Cody’s letter to the New York Sun clearly indicated his familiarity with the plight of Yellowstone, but the misinformation on American Indians and hunting in the park reveals a lack of direct knowledge on the subject.

So why did Cody publicly support these efforts to protect Yellowstone in 1883? Without a doubt, he was unfamiliar with the specific details regarding the issues facing the park, and , at the time, he would not have had a strong economic interest in protecting Yellowstone until later in his life. More than likely, either Sheridan or Grinnell urged Cody to write the letter when touring onstage in New York City, hoping Cody’s celebrity status would garner public support for their efforts to protect Yellowstone National Park.

Cody effectively served Sheridan and his military contemporaries as a scout during the Indian Wars before becoming a national icon through his appearance in numerous dime novels and his stage productions in the 1870s. It is obvious that Cody greatly respected Sheridan – he dedicated his 1879 autobiography to the General. Additionally, the story contained a facsimile letter written by Sheridan praising Cody’s scouting legacy and proclaiming that his life story “will eventually be of real service to the future historians of the country.” If General Sheridan approached Cody requesting his support for protecting Yellowstone, Cody would have readily agreed to do so, in turn supporting his former commander and friend who assisted in his rise as a national hero.

It is likely Cody would have done the same for Grinnell, whom he first me in 1874 during O.C. Marsh’s fossil hunting expedition through Nebraska. During the Marsh expedition, Grinnell also me Frank North who later invested in a Nebraska ranch with Cody and recruited Pawnee Indians to perform in Cody’s first Wild West production. Grinnell returned to Nebraska to hunt with Frank and his brother Luther North, where he renewed his acquaintance with Cody. It is likely Grinnell related his experiences on the Ludlow expedition through Yellowstone to Cody and the North brothers. Although Grinnell later disputed Cody’s claim of killing the Cheyenne Chief Tall Bull to credit Frank North with the deed, in the early 1880s Cody’s and Grinnell’s acquaintance was friendly, and Grinnell may have influenced Cody to voice his support for Yellowstone’s protection.

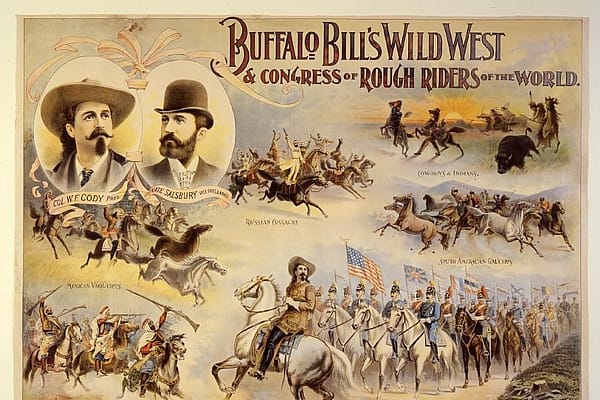

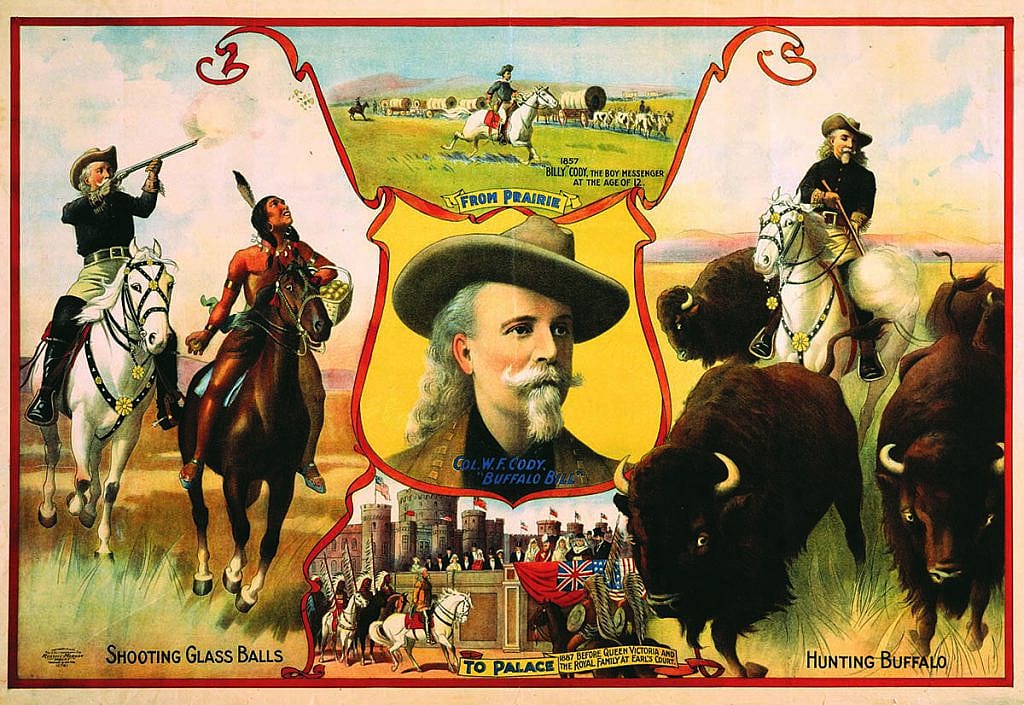

Cody and his publicist Burke may have also been motivated to write the New York Sun letter to promote their new business venture with W.F. “Doc” Carver, an outdoor extravaganza that would eventually become Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. The show honored the passing of the American West, and perhaps Cody and Burke wished to highlight the great ecological changes that occurred int eh region, by focusing the public’s attention on the plight of one of the last wilderness reserves in the United States – Yellowstone National Park. The program from Carver and Cody’s production included tales of bison hunting and a section detailing the importance of the bison and elk herds for providing necessary caloric sustenance for early explorers and settlers. Perhaps Cody and Burke believed that demonstrating the threat to wildlife in Yellowstone enhanced the spectacle of seeing live bison and elk in the forthcoming Wild West production.

Despite Cody’s support, Vest’s Senate bill to extend more protection to Yellowstone failed; however, Vest managed to pass a stipulation to the Sundry Civil Bill that limited the acreage of leases to ten acres and forbade concessionaires from receiving leases that held any scenic attractions. Additionally, the bill stipulated that the Secretary of the Interior could request assistance from the Secretary of War for the military protection of the park, which occurred in 1886 after Congress failed to appropriate funds for the superintendent of Yellowstone. The outcry resulting from the public debate over killing game to feed workers did pressure the Secretary of the Interior to ban the sport hunting of key species within the boundaries of Yellowstone in 1883. Upon taking over the supervision of Yellowstone in 1886, the military superintendent banned all sport hunting and did his best to curtail any poaching of park wildlife.

… The military superintendent banned all sport hunting and did his best to curtail any poaching …

Grinnell later joined forces with a young politician, rancher, and author by the name of Theodore Roosevelt. The two men formed the Boone and Crockett Club, an organization that continued Grinnell’s efforts to protect Yellowstone from railroad developers and to support the military’s efforts to catch and punish poachers who ignored the ban on hunting within Yellowstone. Surprisingly, William F. Cody never became a member of the Boone and Crockett Club; perhaps his legacy as a market hunter deterred this growing sportsman organization from bringing him into the fold, despite his early support for Yellowstone National Park and its wildlife resources.

We may never know why Buffalo Bill supported the efforts to protect Yellowstone, and we can speculate whether this support was heartfelt or motivated by personal connections or business interests. For whatever reason, Cody did publicly voice his support for Yellowstone’s future, placing him in the ranks of the early conservationists demanding increased protection of the natural resources of the American West. This included the few bison that remained in Yellowstone – a species many historians later credited Cody for decimating on the plains.

Today, Yellowstone visitors view wildlife as one of the park’s greatest natural resources, and it is hard to imagine the park without bison, elk, bear, or other wildlife species. The combined efforts of military men like Ludlow and Sheridan, collaborating with early conservationists such as Grinnell, Vest, and Roosevelt, supported the ongoing protection of natural features and wildlife in Yellowstone. This list of early Yellowstone crusaders should also include William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody. Regardless of his motivation, Cody’s public support for the greater protection of the park and its wildlife certainly garnered increased public support for Ludlow, Grinnell, Sheridan, and Vest’s efforts to protect Yellowstone National Park and its wildlife – ensuring that both remained national treasures.

Author’s Note

The author expresses his thanks to Paul Schullery, Lee Whittlesey, and Paul Hutton for their insight on William F. Cody’s thought-provoking letter to the New York Sun. I also wish to thank Adam Hodge, a graduate student from the University of Nebraska who is conducting research on behalf of the Papers of William F. Cody, for locating this intriguing letter from Cody.

About the author

Jeremy Johnston is a descendant of John B. Goff, a hunting guide for President Teddy Roosevelt. Johnston grew up hearing many a tale about Roosevelt’s life and times. For fifteen years, he taught Wyoming and western history at Northwest College in Powell, Wyoming. During that time, Johnston received two research fellowships at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. he currently serves as Managing Editor of the Papers of William F. Cody and the Curator of the Buffalo Bill Museum.

Post 239

Written By

Liz Bowers

Liz Bowers is a Wyoming college student working with the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in summer 2018 to gain experience in Public Relations. This includes activities with social media, review sites, events, writing, and photography. In her spare time, Liz enjoys hiking, trail riding, and stories of all shapes and sizes.