Arab Performers in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Summer 2018

Arab Performers in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West

By Danielle Haque, PhD

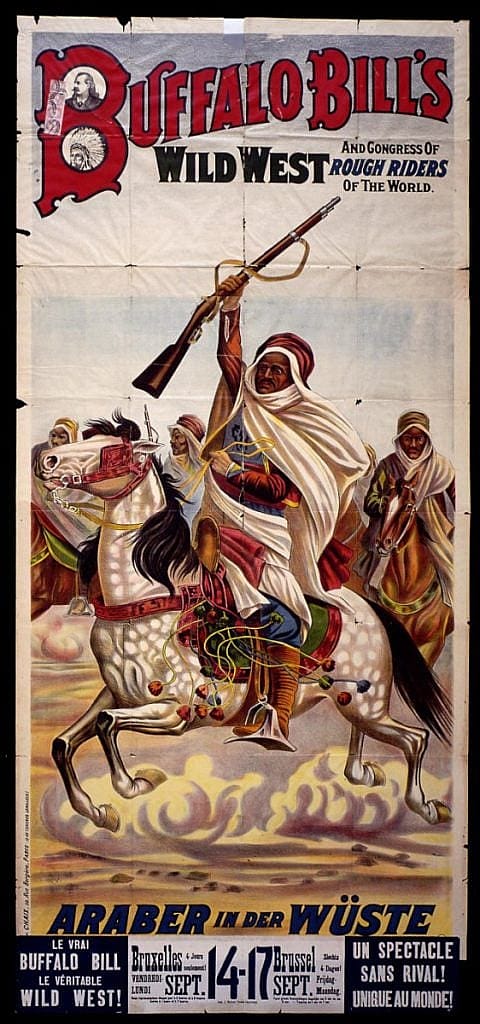

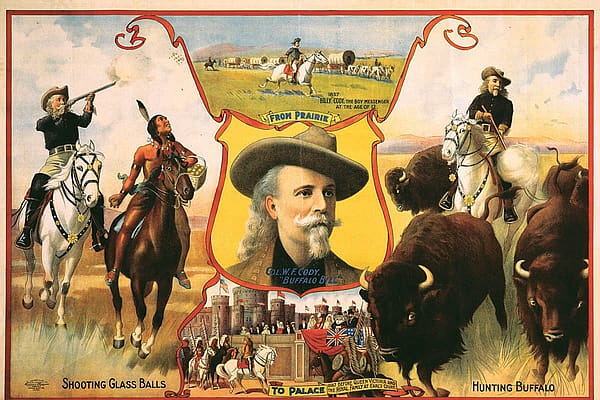

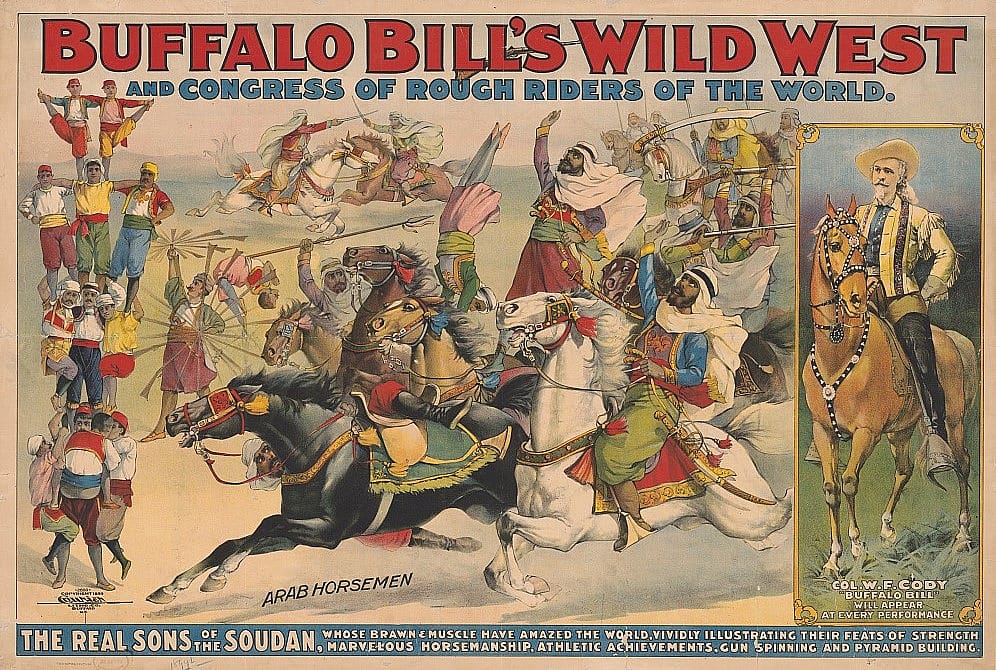

In 1893, Chicago hosted the World’s Fair or the World’s Columbian Exposition. The electric fair has long been associated with Buffalo Bill, and by different accounts, between 2 and 3.8 million of the twenty million visitors to the fair also attended the Wild West exhibition. Camped right outside the gates of the Columbian Exposition, Buffalo Bill’s show advertised in the Rand McNally official guide to the fair, stating that “All Roads Lead to Buffalo Bill’s Wild West.” The Chicago Globe confirmed this triumphant claim that same year with its headline, “All Roads Do Seem to Lead to Buffalo Bill’s Big Show.” The Chicago fair featured the debut of a new feature of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, an Arab performers troupe, meaning that millions of Americans saw them perform. That very same Rand McNally advert boasted that the show now had “Genuine Arabs of the Desert.”

There is substantial scholarship on how the Wild West showcased the settler-colonial relationship between Native Americans and European Americans; promoted imperialism at home and abroad; interacted with and reinforced the race-oriented theories of Anglo-Saxonism and Aryanism; and helped create the popular images that mainstream America has about the West and Native Americans. However, there has been very little writing about the Arab performers in the show, particularly as the historical records for the non-Native American performers is sparse. Western historian and Buffalo Bill scholar Louis Warren notes that we know more about the Native American performers than any other group because of the archival footprints created by the tug of war between the show and the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Dr. Haque’s larger research project addresses the absence of a historical narrative about the role of the Arab performers in the show. She also wants to analyze how the representation of these performers helped created the popular image of the “Arab” in the United States.

In this article, Dr. Haque introduces some archival materials from the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, and gives an overview of the Arab troupe’s participation in the Wild West.

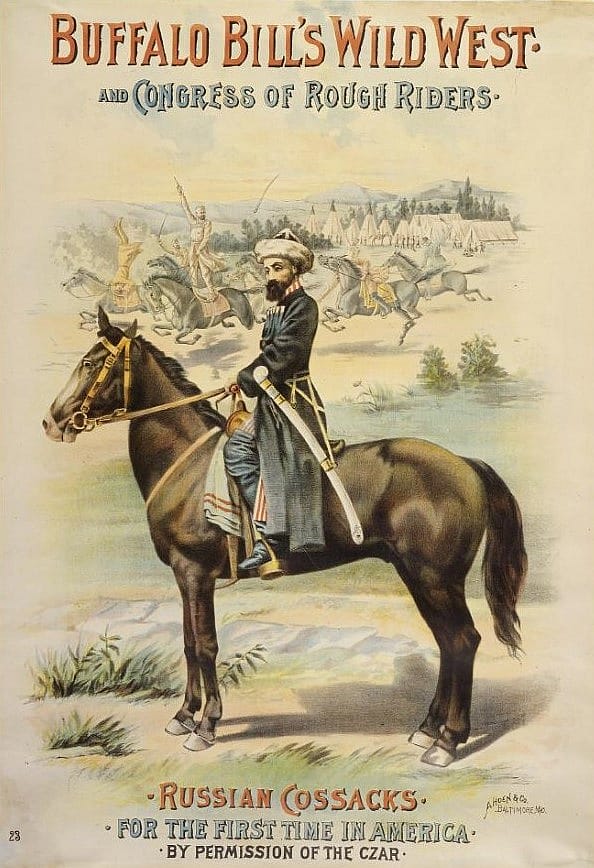

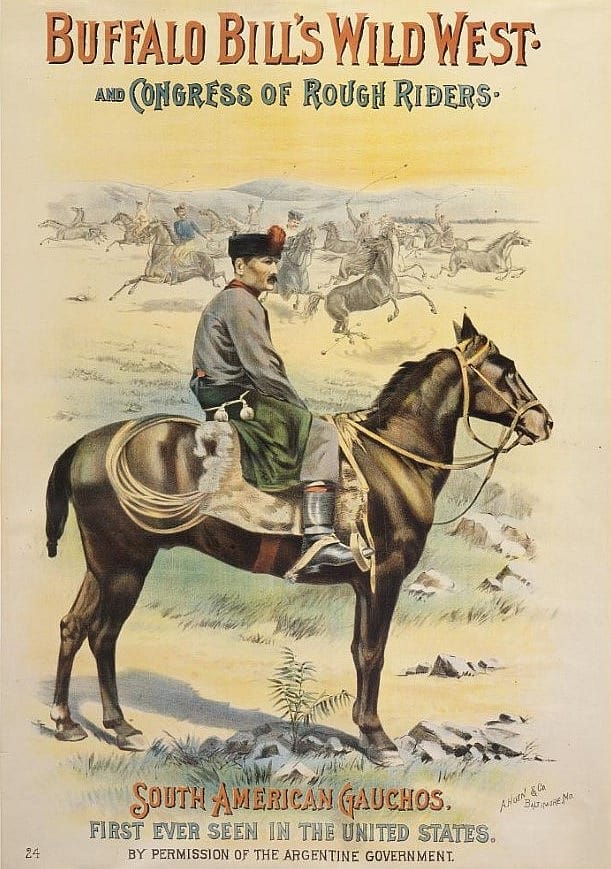

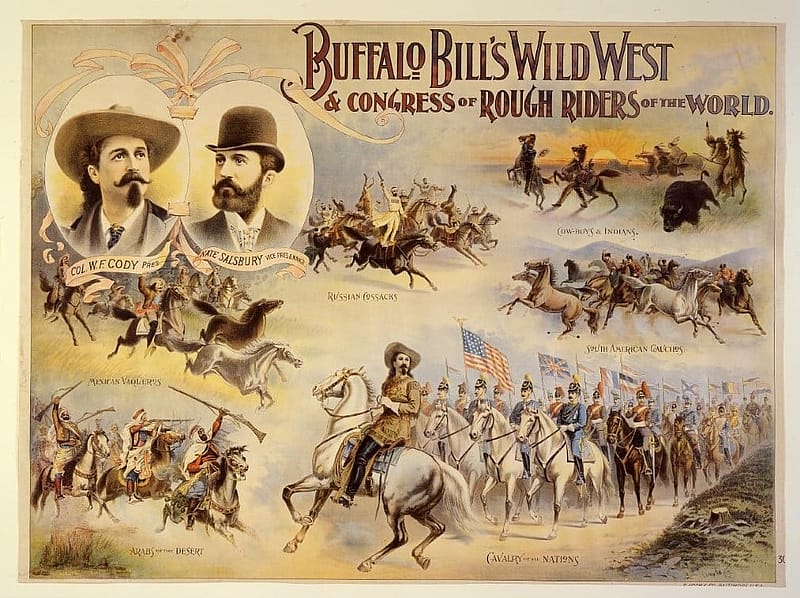

The Wild West Goes International

It is unclear exactly how the Arab performers came to join the show. It’s possible that Major John Burke brought them aboard, as he had previous experience managing touring Arab performers. On the other hand, an Arab troupe that visited the show in Paris in 1887 may have inspired co-owner Nate Salsbury. Undoubtedly, the decision was based on increasing attendance and on expanding the already existent non-western part of the show, which by 1893 already included Cossacks and Gauchos. The trend of internationalizing a show that began as a demonstration of America’s conquest of the West was directly in line with American foreign policy at the time. In the early part of the nineteenth century, U.S. foreign policy had been expansionist overseas and reached a forceful halt during the Civil War and Reconstruction.

By the 1890s though, American industry, trade, and cultural production were expanding globally at unprecedented rates. Buffalo Bill’s wild West promoted the ideal of an expanding America both domestically and abroad. Many have maintained that the show’s excursions overseas and the inclusion of the Congress of Rough Riders of the World transformed the drama about American civilization’s “triumph,” over the American West and its indigenous peoples, and replayed it writ large as a “triumph” that would include the entire world.

The late 1800s and early 1900s saw increasing migration to the United States from the area known as Greater Syria, which was then part of the Ottoman Empire (and had been since the sixteenth century). Many or most of the Arabs that performed through the years with Buffalo Bill immigrated to the United States from the Ottoman Empire. At the end of the nineteenth century and before World War I, the Empire, which dates from 1299, was consciously working globally to promote an image of itself as a modern, European nation. The Ottoman state did this in many ways, including art, creating the Imperial Ottoman Museum, and regulating and curating an image of its past to portray itself as a modern member of the family of nations.

Additionally, the Ottoman state hosted pavilions at international fairs such as the 1893 Columbian Exposition. These pavilions presented the Arab periphery of the Ottoman Empire as a people/territory in need of civilizing – in many ways paralleling how Americans at the time perceived the Native American population. The comparison was not lost on the Ottoman people, the Ottoman poet Ziya Gökalp wrote that he hoped his homeland would become “the free and progressive America of the East.” Conversely, a 1909 program for the Wild West describes the show as including an arena where:

…the onlooker witnesses varied exhibitions of horsemanship, wherein the dusky-skinned Arabian vies with the American cowboy in displays of equestrian expertness; the camp life of the Native American Indian is shown in contrast to the nomadic domiciles of the desert-born Bedouin.

The Native Americans and Arab performers – who were billed variously as Riffian Arabs, Bedouins, Moors, Syrians, and Berbers – are portrayed as nomadic. They were represented as somehow unattached to the national landscape while being naturally attuned to it and depicted as a premodern culture and people disappearing from the modern nation-state.

The Wild West’s Arab Troupe

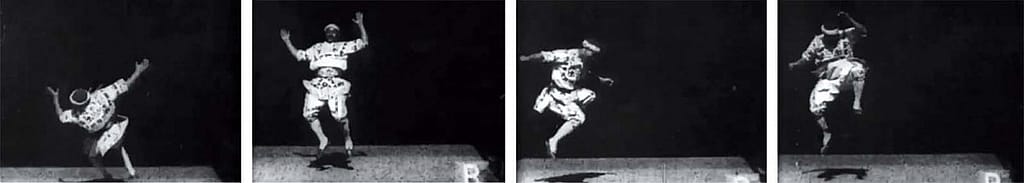

In the show, the Arab contingent performed multiple roles. In the 1898 program, the Arabs are listed as participating in the Grand Review – their featured act was called “A Group of Riffian Arabian Horsemen” – as well as being a part of the “Race of Races.” That event involved pitting the various nationalities in a race against each other. A 1904 program lists the Arabs as participating in feats of horsemanship as well, but that was their secondary performance skill. Originally the Arab performers were acrobats. The Rough Rider Annual of 1902 wrote that the Arabs were “athletic gymnasts of a strange kind it would repay a journey across the great desert to see.” The Arab tumblers twirled rifles so quickly they looked like “a thousand sunbeams.” The acrobats built “high living pyramids, with the agility of cats, and the strength of tigers.”

The Arabs were able to showcase their athleticism and thespian talents in a feature called “The Far East or a Dream of the Orient.” This feature combined a storyline that begins with a group of western tourists taken hostage by a tribe of Bedouins under the very shadow of the Egyptian pyramids. With exotic animals and music, Japanese acrobats and other non-white performers were able to showcase their skills within this Arabian frame story. However, unlike many of the vignettes that featured Native Americans, the white American actors were never really under “threat” of physical harm. Instead, they are entertained by music, menagerie, and performances. At the end, there is no charge of white masculine power to rescue them; rather, the ransom money arrives, and the hostages are free.

According to Sarah Blackstone, in her book Buckskins, Bullets, and Business: A History of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, only four full rosters exist for the show: the years 1896, 1899, 1902, and 1911. These rosters demonstrate that through the course of the Wild West, at the very least, forty individuals performed in the Arab troupe with the show. Tracking down the career and life trajectories of some of these individuals gives a sense of the identity of these performers and how they lived outside the collective acrobatic group they represented.

One intriguing all-American connection was made in Paris in 1889, when Buffalo Bill sat down to a hearty breakfast with Thomas Edison. This Parisian summit would prove fruitful for the early film industry, the Wild West, and the Arab performers of the Wild West. W.L.K. Dickson directed two of the show’s Arab performers – Hadj Cheriff as a knife juggler and Sheik Hadji Tahar as a gun juggler – and filmed them both in Thomas Edison’s Black Maria Studio in West Orange, New Jersey, on October 16, 1894. Cheriff (listed as Hadj Sheriff in the 1896 roster) was identified in both the 1896 and 1899 Route Books as a Whirling Dervish, giving insight into the way in which these acrobats also performed cultural “types” such as whirling dervishes (Sufi Muslims who use dance in their mystical religious practice), roving Bedouins, and Riffian horsemen.

In 1896, Sheik Hadj Tahar (in 1899 identified as Sheik Hadji Tahar) headed the Arab performers and later was listed as the “Chief” in the 1899 roster. After leaving the Wild West, he continued to perform with his acrobatic troupe at venues such as Chutes Park, an amusement park in Los Angeles in 1902. Tahar would acquire some notoriety as well when he became embroiled in a kidnapping scandal in San Francisco in 1908. It’s unclear with what, if anything, he was charged, and by May 1909, he was performing again in San Leandro, California. In 1913, Tahar proposed a settlement scheme in southern California for the creation of a sizable Arab colony. These ethnicity-based development plans were not that unusual at the time and ranged from lurid scams by confidence men like Herbert A. Firth to official government proposals.

Tahar appears to have had a further career in film as the technical adviser to one of the first Tarzan movies, Revenge of Tarzan, filmed in 1920. In a 1975 interview, actor Eddy Field stated that Tahar was 82 at the time the movie was filmed. If accurate, that would mean Sheik Tahar was born in 1838, and thus traveled with the Wild West into his sixties.

George Hamid, Boy Acrobat

The most famous of the Arab performers was George Hamid, who published a 1956 autobiography (as told by his son George Hamid Jr.), Boy Acrobat. It was reworked and expanded by his son in 2004 as The Acrobat: A Showman’s Topsy-Turvy World from Buffalo Bill to the Beatles. George Hamid joined the Wild West in Marseilles, France, in March 1906, during the show’s three-day stand in that city. Hamid was born in Broumania, Lebanon, (then the Ottoman Empire) and was the nephew of Ameen Abou Hamad who was identified in the 1902 and 1911 rosters as the leader of the Arab performers. Hamid disembarked with his cousins Shaheen and George Michael through Ellis Island in 1907. Arriving on the ocean liner Potsdam, his name was entered as Jerjy Aban Hamad, although he was listed as a performer with the Wild West under the name Gargie Abou Hamad.

Much of what Hamid describes in his autobiography is hard to verify. For instance, he claims to have been taught English by Annie Oakley, which, as Warren points out, is impossible. She was no longer with the Wild West during Hamid’s tenure.

Hamid’s wry autobiography includes fascinating insights into the show, his reliability aside. He writes that he had to learn to ride a horse to participate in the “Ride of Death.” This indicates that the acrobatic troupe were not the “natural equestrians of advertisements, but only learned horsemanship upon joining the Wild West. Hamid also writes that when he joined the show, three of the “Arabs” were actually not Arabs at all. Warren states that the Wild West never passed off non-Native Americans as Native Americans, but was not entirely strict when it came to authenticity in portraying other ethnicities. Hamid’s anecdote thus reveals the pageantry involved in performing “Arabness” in the show.

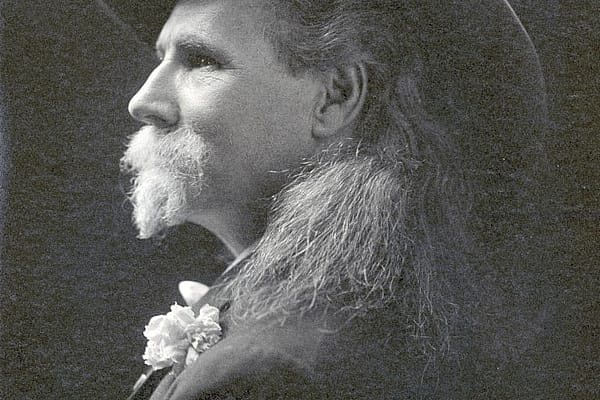

Hamid tells a fascinating story, including his first glimpse of William Cody in Marseilles. He describes him as “a straight square, white-haired, white-bearded man who looked like a Prophet out of Grandmother’s Bible.” Hamid turns the Biblical Garden of Eden on its head, telling us that his grandmother described the United States to him by saying, “I have told you stories about Bible lands flowing with milk and honey, about the Garden of Eden. There are no such places on earth. Where you are going [America], Puabla [his nickname], is close to it.”

As an immigrant to America in the early twentieth century, Hamid was part of that much larger flow of Arab migration, particularly from Syria and Lebanon, that was coming to the United States. Ironically, when the adult George-Hamid returned to Lebanon after becoming a successful entertainer and promoter – eventually owning some of the major venues in Atlantic City, New Jersey, and running the New Jersey State Fair – he notes that his cousin Shaheen who accompanied him said, “George… we had to become Americans to see the Middle East.”

From 1893 until 1913, Arab performers worked, traveled, and lived with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. Their inclusion in the show mirrored the increasing American interest in the Middle East as the United States strove to compete with entrenched European interests in politics, trade, and massive infrastructure railway projects like the Chester Project. The Arab performers also mirrored the growing Arab immigration to the United States which happened both in major cities like New York City and Detroit, as well as small rural areas like Mankato, Minnesota, or Ross, North Dakota. The performers, as seen in advertisements and newspaper reviews of the show, are often represented as performed stereotypes of “Arabness” for their audiences. Yet their inclusion in the show and exposure to large audiences across the United States, also point to the long, vibrant history of Arab and Arab Americans participating in shaping American culture.

About the author

Dr. Danielle Haque is Professor of English at Minnesota State University-Mankato. She served as a Buffalo Bill Center of the West Research Fellow in 2017 and extends a special thank you to the archivists of the Papers of William F. Cody and the staff at the Center’s McCracken Research Library.

Post 237

Written By

Liz Bowers

Liz Bowers is a Wyoming college student working with the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in summer 2018 to gain experience in Public Relations. This includes activities with social media, review sites, events, writing, and photography. In her spare time, Liz enjoys hiking, trail riding, and stories of all shapes and sizes.