Charlie Russell’s Books – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Fall 2010

Charlie Russell’s Books

By Brian W. Dippie, PhD

Charlie Russell’s library points to a book reader, not a book collector,” writes Dr. Brian Dippie. In the words that follow, Dippie shares insight into the artist’s bookshelves, complete with Russell’s own comments—grammatical errors and all—that preserve the authenticity of the artist’s remarks.

After Nancy Russell died in Pasadena, California, on May 24, 1940, her estate was divided, and the books she owned sold. An appraiser described them as a “miscellaneous lot…consisting of approximately one hundred volumes, being principally western stories, travel, and biography.” He valued them at $50.

Most were books once owned by her husband Charles Marion “Charlie” Russell (1864–1926), who died fourteen years earlier, and a few were Nancy’s own copies. They were acquired by an established Los Angeles firm, Dawson’s Book Shop, and offered for sale that December. At least one of the Russells’ old friends was appalled. “I had a letter from Joe De Yong yesterday—giving me the address of a Los Angeles book shop—that is selling the C.M. Russell collection of books—that Charlie had collected & kept—all the years of his life,” William S. Hart fumed. “I wrote Joe and told him that was one store I’d keep away from—Gosh! Its sacreledge [sic]—That’s what they do to us when we kick off.”

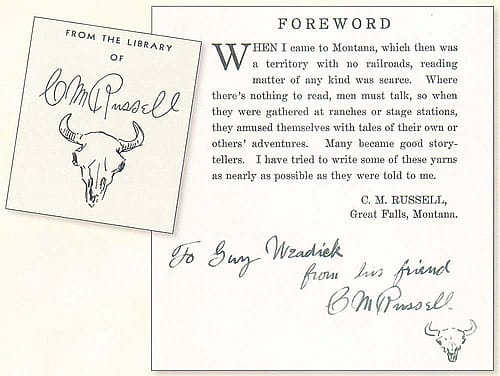

De Yong, Russell’s only protégé who had become like a member of the family over the years, did not share Hart’s misgivings. He secured several of the books for himself, wrote an introduction to the catalog of Russell’s library that Dawson’s issued in February 1941, and provided the cover art. By then, the Russell books had been cherry-picked with many of the best inscribed copies already sold to interested collectors—books presented to Russell by such luminaries as Will Rogers, George Bird Grinnell, and Will James.

“My poor catalog really is stripped of its Russell treasures,” Dawson’s sales manager lamented. Consequently, the pub- lished catalog, while a valuable guide to Charlie Russell’s books, is incomplete. But Dawson’s did do something important: They designed a bookplate with Russell’s buffalo skull insignia and the words “From the library of C M Russell.” The bookplate was pasted at the front of every book from the Nancy Russell estate. It serves as the homing device for anyone on the trail of Charlie Russell’s books.

Why care about the books Russell owned? First, the fact that he read counters the impression that he was an unlettered cowboy who learned everything from experience and nothing from the printed page. His library, like that of any artist, suggests the range of his interests and, because so many of his books were gifts, the generous circumference of his circle of friends. Books provide a unique insight into the influences on an artist’s work. We come to understand Frederic Remington better through his library in Ogdensburg, New York, and we get to know another side of Russell through his books.

We all realize that owning a book does not necessarily imply reading it. But Russell’s library, on the whole, closely corresponds to the things he most enjoyed: from illustrations and western verse—often by people he knew—to the stories that fired the imagination of a born romantic who, as an impressionable child in St. Louis, Missouri, devoured tales set on the western frontier.

A storyteller in paint, Russell was in awe of those who could paint with words. “Betwine the pen and the brush there is little diffornce but I belive the man that makes word pictures is the greater,” he told a writer who had sent him a copy of his novel about the North West Mounted Police. He owned the books of storytellers, from Mark Twain and Bret

Harte to Rex Beach, Rudyard Kipling, and O’Henry.

Russell liked humorous tales; his own Rawhide Rawlins stories were praised by the popular humorist Irvin S. Cobb as “full of good local color, good character-drawing, and good lines.” The artist’s collection had books by George Ade and Ellis Parker Butler, whose bestseller Pigs Is Pigs was illustrated by Russell’s friend Will Crawford, and compilations like John Bain’s Cigarettes in Fact and Fancy. Russell relished the boys’ adventure stories he had grown up with and had a particular fondness for Harry Castlemon’s books judging from the number of titles he bought or was given, and in one instance, extra-illustrated with watercolor sketches.

Western novels—almost all of them gifts from the authors including Andy Adams, B.M. Bower, Robert J. Horton (Russell called him “Sporticus,” after his days as sports editor of the Great Falls, Montana, Tribune.), Emerson Hough, Henry H. Knibbs, James Willard Schultz, Bertrand W. Sinclair, Frank Spearman, and Stewart Edward White—vied for space on his bookshelves with classics by Cooper, Dickens, Dumas, and Sir Walter Scott.

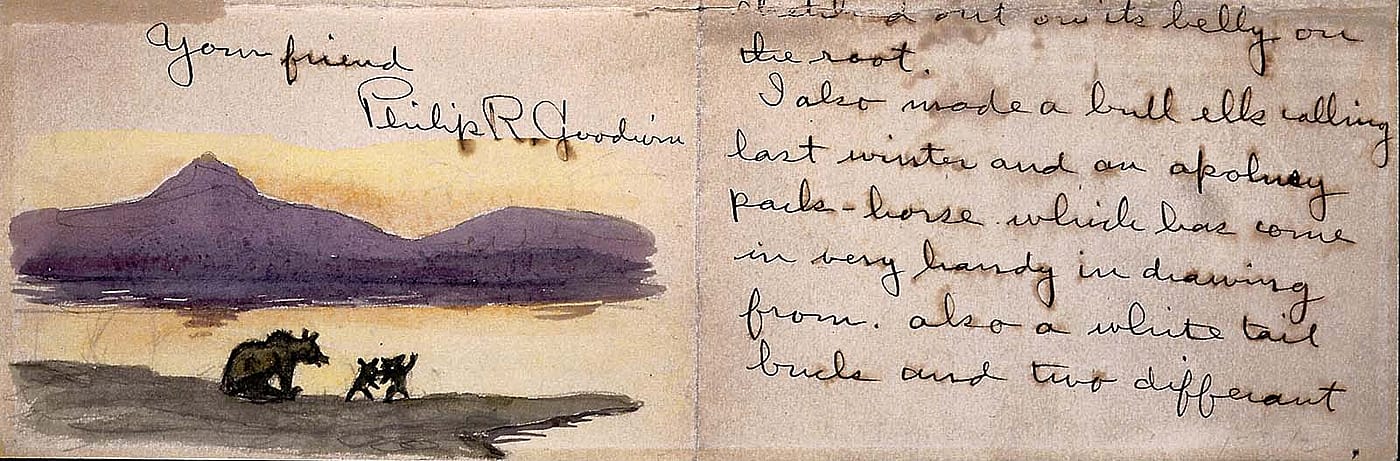

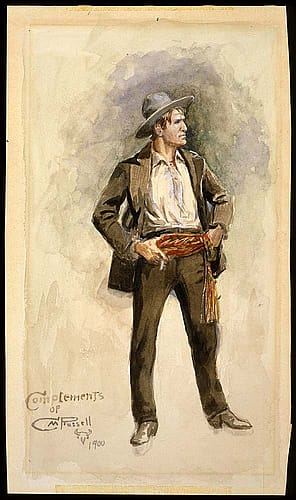

Russell clearly cherished books with pictures of exotic foreign places and peoples, and with plates showing birds and wildlife. He subscribed to National Geographic Magazine for years and saved issues that tickled his fancy. On copies featuring photographs and color plates of birds and small mammals of North America, he wrote “Good” and “Small animals.” He had books illustrated by Howard Pyle, the founder of the “Brandywine school” that trained illustrators from Russell’s friend, the wildlife and sporting artist Phillip R. Goodwin, to such stars of the “golden age of illustration” as Harvey Dunn and N.C. Wyeth—all represented in his collection.

As a Great Falls librarian, Josephine Trigg knew books, and as the Russells’ neighbor and confidante, knew Charlie’s taste. With her mother, she gave him elegant editions of Pyle’s The Story of King Arthur and His Knights and Washington Irving’s Rip Van Winkle illustrated by Arthur Rackham. Russell’s own peerless illustrations for Frank Linderman’s collections Indian Why Stories (1915) and Indian Old-Man Stories (1919) depicted animals as important characters. It is not surprising, then, that Russell owned copies of Beatrix Potter’s The Tale of Mrs. Tiggy-Winkle and The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin, both gifts from Trigg.

Naturally, western history figured prominently on Russell’s book shelves. He liked firsthand accounts that predated his personal experience in the West in the 1880s, carrying him back to the days when the buffalo roamed in seemingly limitless numbers; Indians rode proudly across a land they owned; and fur traders were making their first, tentative forays into a still unfamiliar country. He also enjoyed books that recounted the experiences of frontiersmen and cowboys who were his near contemporaries—Granville Stuart, Robert Vaughn, Luther S. “Yellowstone” Kelly, James H. Cook, Edgar Beecher Bronson, and William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody himself—as well as historical narratives describing life in a West that had vanished forever.

In 1916, Paris Gibson, a pioneer with a progressive vision who founded the city of Great Falls in the mid-1880s, presented Russell with the first volume of Hiram M. Chittenden’s The American Fur Trade of the Far West (1902) “because of his interest in the early history of the Rocky Mountain Country drained by the Missouri River.” Gibson also notified a publisher of western Americana, the Arthur H. Clark Company (then located in Cleveland, Ohio) of Russell’s bookish interests. Clark responded at once, addressing Russell as “a collector of old and rare books dealing with the Pioneer History of the Rocky Mountain country.” That was something of a stretch, and the next year, the Russells returned a copy of a genuinely rare book sent by Clark, John K. Townsend’s Narrative of a Journey Across the Rocky Mountains (1839), “as we have all the material in other books contained in that one.” But they were smitten with a two-volume fictionalized history of the Pilgrims, Frank Gregg’s The Founding of a Nation (1915), the only non-western title Arthur H. Clark would ever publish. “They really are fine books,” Nancy wrote for the both of them, “and we are glad to add them to our library.”

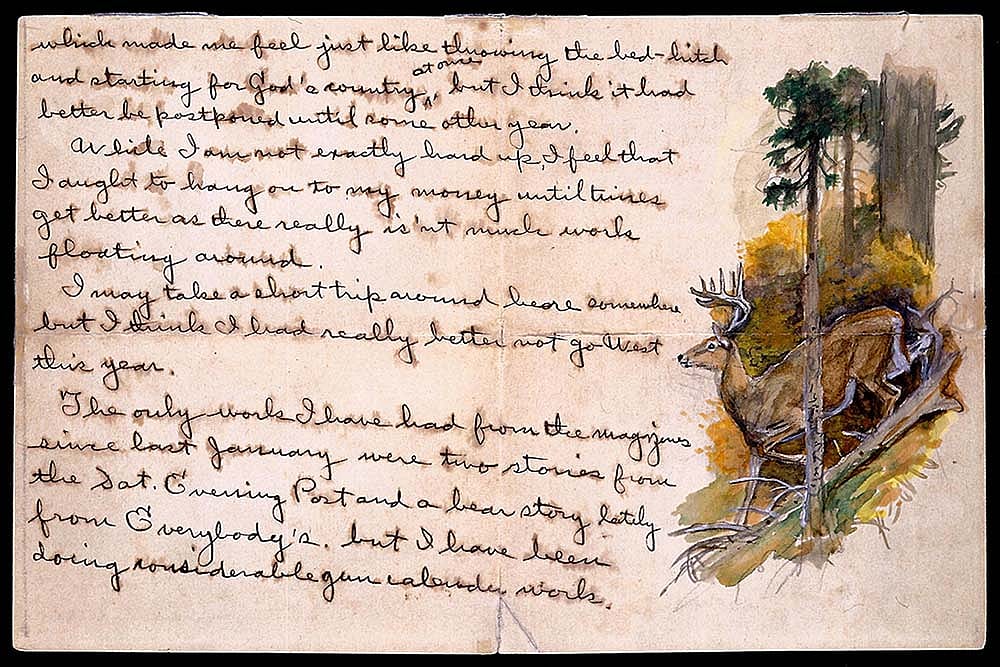

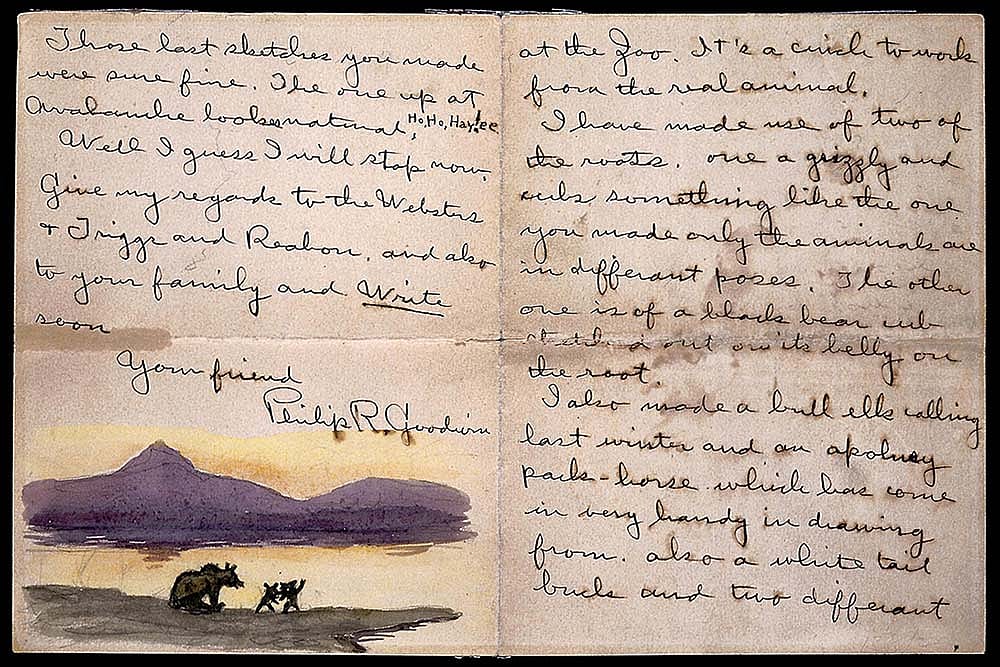

Phillip Goodwin letter page with sketch of a deer. 26.83.2

Phillip Goodwin letter page with sketch of a deer. 26.83.3

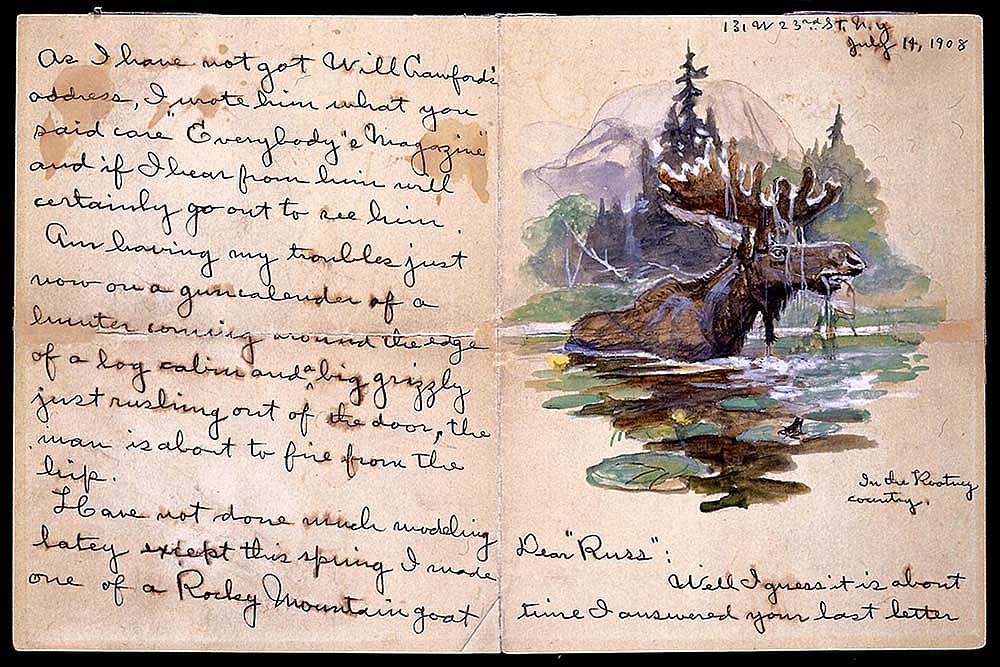

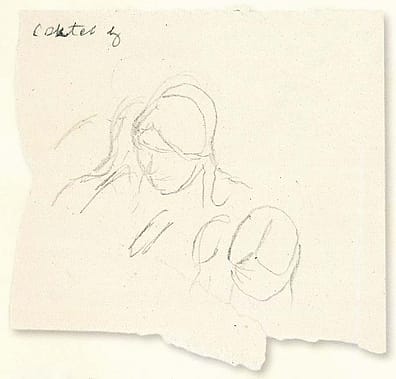

Many of Russell’s books were illustrated by friends including the artist Phillip Goodwin, who, like Russell, illustrated his correspondence as in these images from his letter to Russell, dated July 14, 1908. Phillip R. Goodwin (1881–1935). Dear “Russ.” Moose in pen, ink, and watercolor. 26.83.1

Charlie Russell’s library points to a book reader, not a book collector. When Frank Linderman began work on a mountain man novel that would be published in 1922 as Lige Mounts: Free Trapper, Russell gave him the relevant books in his collection—Washington Irving’s Captain Bonneville, Francis Parkman’s The Oregon Trail, and T.D. Bonner’s The Life and Adventures of James P. Beckwourth. He even provided a critique of Beckwourth’s claims. “Jim might not have been a liar but he crouded the edg mighty close,” Russell observed. “He dident hardly leave a nest egg for the black feet but there is still a fiew left he dident just take scalps he harvested them.”

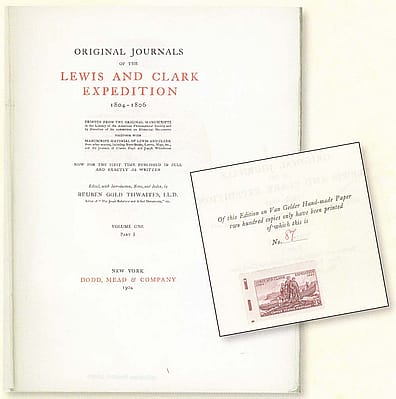

In short, Russell shared books more than he collected them. What had misled Paris Gibson was probably the one bibliographical treasure Russell did own—a set of the Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition published in an edition of two hundred copies in 1904–1905. That very set today resides in the McCracken Research Library at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming, the gift of the Charles G. Clarke family.

Given the artist’s long-standing interest in Lewis and Clark, it makes sense that Russell would own a complete edition of the original journals. According to a note by Clarke, when he acquired the set from Dawson’s early in 1941, only the first three volumes (or parts) of the fifteen-volume set were “cut.” In books at that time, pages were often joined and had to be slit open to be read. Russell had opened only the first three volumes in his set of the Lewis and Clark journals, which took the expedition up the Missouri River as far as Great Falls.

“In those,” Clarke noted, “were found a few sketches made by Mr. Russell, probably placed there as page markers.” Clarke opened the rest of the volumes in researching his own book, The Men of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (1972). He extensively annotated and extra-illustrated each volume as he went along, effectively eliminating almost every trace of Russell’s prior ownership.

Yet Russell’s presence lingers on. The fine plates by Karl Bodmer were always visible whether the text was readable or not. While the little scraps of paper that Russell used as book marks have not been found, and their place in the relevant volumes not recorded, Clarke took the trouble to paste one of them at the front of the first volume. It shows an Indian’s head seen from above and lays a lasting claim to this set of books as Charlie Russell’s own.

Exactly when Russell acquired the Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition is unknown. Paris Gibson’s impression that he was a book collector was formed by the beginning of 1916. However, the first mention of Russell’s set of the journals dates to 1917 when Joe De Yong, staying with the Russells at the time, told his parents that he was reading them. The Clarke book collection provides another clue. In his copy of Russell’s illustrated letters, Good Medicine, Clarke inserted a postcard that was sent to Russell by a friend in Park City, Montana, on March 2, 1917. Presumably it, like the little scraps of paper with sketches, had also served Russell as a book mark. Most, though not all, of Russell’s paintings of the Lewis and Clark Expedition were behind him by then, including his masterful mural Lewis and Clark Meeting Indians at Ross’ Hole (1912) in the Montana State Capitol in Helena.

Paging through Russell’s own copies of the Lewis and Clark journals brings a story to mind:

In 1913, Frank Linderman, with Russell and two others, took a float trip down the Missouri River in Montana from Fort Benton to the mouth of the Judith River, retracing in reverse Lewis and Clark’s journey up the Missouri in 1805. Linderman recalled that Russell brought with him a copy of the expedition’s journals, and we can picture him reading aloud from one of these very volumes in his halting, schoolboy manner, stopping frequently to spell out words “for our pronunciation” as the current carried the four men along and the river bank streamed by, erasing 108 years as they joined Lewis and Clark on their epic adventure.

And that’s what books can do. Charlie Russell’s books allow us to sit behind him in his log cabin studio, observing, as he conjured up visions in paint of the West that has passed.

About the author

Dr. Brian Dippie taught history at the University of Victoria in British Columbia, Canada, from 1970 until his retirement last year. He earned a bachelor’s degree from Canada’s University of Alberta in Edmonton, a master’s degree in American Studies from the University of Wyoming, and a doctorate in American Civilization from the University of Texas-Austin.

A prolific writer and lecturer, Dippie focuses on western American history and art; the mythic West; American Indian policy and the Indian wars; and the history of racial stereotyping in America. He is an expert on artists George Catlin, Frederic Remington, and Charles M. Russell, explaining that, “Artists played a key role in the perpetuation of western myths.” Dippie served on the Buffalo Bill Center of the West’s McCracken Research Library Advisory Board from 1996–2003.

Post 247

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.