Karl May, The Storyteller Old Shatterhand – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Spring 2011

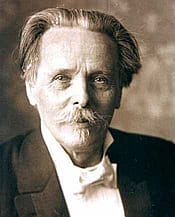

Karl May: “I Am Hakawati.” The Storyteller, Who Was Old Shatterhand

By André Kohler

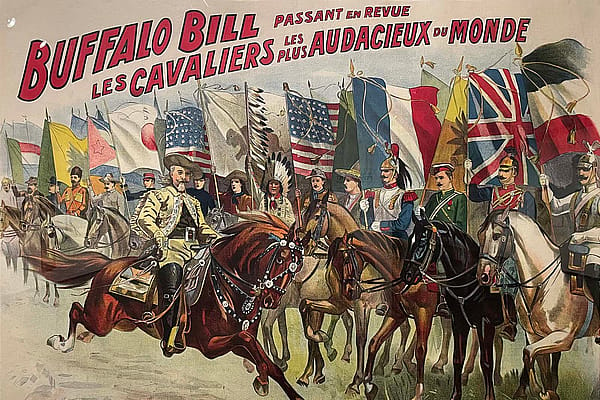

For Germans, Karl May (pronounced “my”) is as recognizable as William F. Cody is to Americans—and he’s had nearly as many adventures as his contemporary, too. Here, André Kohler of the Karl May Museum in Dresden-Radebeul, Germany, shares the story of “Old Shatterhand.”

- William F. Cody biographer Don Russell introduces Karl May in his 1960 work The Lives and Legends of Buffalo Bill, letting readers know that there is a museum dedicated to Karl May in Munich, Germany—an organization that commemorates the days of Buffalo Bill.

- Sarah J. Blackstone’s Buckskin, Bullets and Business: A History of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West (1988) tells how dime novels started to shape the imagined American West. She notes that May was a German novelist who had never been to America, whose work was translated into twenty languages, and who was deemed Germany’s [James Fenimore] Cooper.

- In Buffalo Bill’s America (2005), Louis Warren refers to Karl May in several details in his thorough research about Buffalo Bill, specifically mentioning May’s most famous literary characters: the heroic German Old Shatterhand and the Apache chief Winnetou, his Indian sidekick.

For me, these were interesting facts to discover during my research at the [then-named] Buffalo Bill Historical Center as a Cody Institute for Western American Studies (CIWAS) research fellow in fall 2010. Or, as an American might say, “This was news to me!” Coming from the Karl-May-Museum/Foundation in Germany, I knew there were errors to be amended here very quickly:

- The Karl-May-Museum is not in Munich but in Dresden-Radebeul, Germany;

- Karl May really did visit America near the end of his life in 1908 when he travelled to Niagara Falls as a tourist;

- May’s leading novels are translated into forty languages, not just twenty; and

- Winnetou in Europe is kind of an icon of the American Indian, not merely a sidekick.

Karl May is one of Germany’s most admired writers, becoming myth and part of German popular culture. He is commemorated not only in scholarly literature, but his stories and heroes fill up open air theatres with several hundred thousand visitors each summer all over Germany. Those stories provide the content for movies and documentaries, as well as the three-day long Karl-May-Festival that takes place in spring each year—an event that draws more than twenty thousand guests to Radebeul.

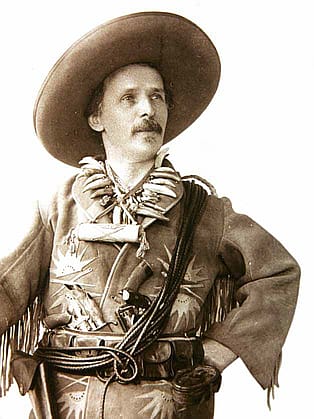

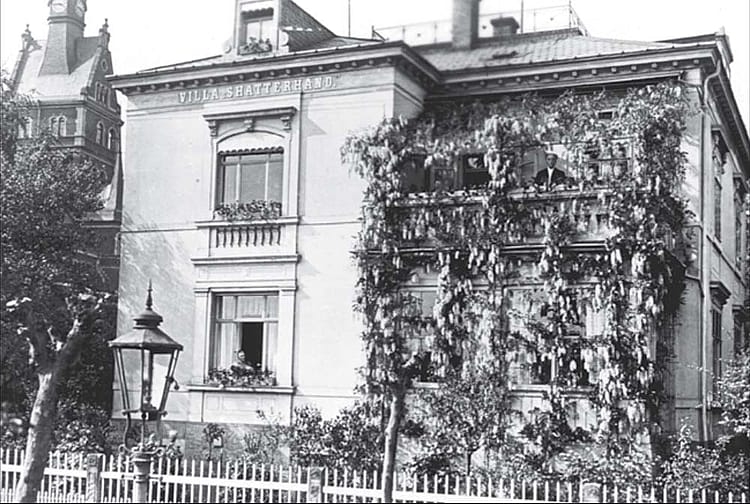

The May myth originated at the Villa Shatterhand in Radebeul. Karl Friedrich May (1842–1912) was as much Old Shatterhand himself as William Frederick Cody (1846–1917) was Buffalo Bill. What follows is an overview of Karl May’s life.

“Your imperial majesty, should I as a cowboy or as a writer conduct the conversation with you?”

Karl May asked this question at the beginning of his lecture before the royal family in Vienna, Austria, February 23, 1898. By this time, he had climbed the pinnacle of success. He was almost 56 years old, but in his mind, bright as a kid and vivid as a young man flourishing with power and self-confidence. His travel tales were bestsellers all over Germany; his stories inspired by the American West were sought throughout the country. It is little wonder that May had to ask royalty what persona they expected to meet in him.

The year before, in July 1897, the German Bayerische Kurier reported on a public lecture Karl May presented in front of his keen audience, noting that “…a crowd of several hundred people of the fast-rising celebrity, the world traveler, and writer Dr. Karl May”…assembled in the dining room of the Trefler hotel in Munich. “They wanted…to see the popular travel/novel writer face to face and pay homage to him personally.”

The account continued: “Not only were there students, there were also many mature men and numerous ladies observed at the auditorium…” High school students, as well as adults from all layers of society—publishers, journalists, physicians, workmen, chaplains, and aristocrats—were eagerly reading May’s stories and waiting for the next adventure to be told. Newspapermen and publishers were yearning for the next manuscripts to satisfy their readers.

Karl May lived in Dresden-Radebeul at his villa, Shatterhand, named after his fictional character—the very hero and first-person shooter of his narratives about the American West. Shatterhand was so named because of his ability to knock out his enemy with a fist. In a chapter titled “A Greenhorn,” in one of May’s most victorious books, Winnetou, Volume 1, we read how the young German—new to the West—works as a survey engineer at a railroad building camp and ultimately gets into some trouble with Mr. Rattler:

“Knock me down?” he [Rattler] laughed. “This greenhorn is really silly enough to believe [he can]…” He couldn’t finish, for I [Shatterhand] hit Rattler on the temple with my fist. He was knocked unconscious and crashed like a log. For a few moments, no one said a word. Then one of Rattler’s companions exclaimed, “What the devil! Are we going to look on as this no good Dutchman beats up our chief? Let’s get him!”

He jumped at me. I received him with a kick in the stomach, an infallible way of bringing down an opponent, but it is essential to stand firmly on the other foot. The attacker fell. Loosing [sic] no time, I jumped on him and knocked him unconscious as well. Then I quickly got up, pulled both my revolvers from my belt, and called out, “Anyone else? Come on!”

White [the chief survey-engineer in the story] looked on in amazement, his eyes wide open. Now he shook his head and said without a trace of insincerity, “…I wouldn’t want to get into a fight with you. They should call you Shatterhand since you can knock down a man as tall and as strong as a tree with a single blow. I’ve never seen anything like it.”

The suggestion seemed to please little Sam Hawkens [the loyal and sympathetic companion of Shatterhand]. He cackled. “Shatterhand, hee hee hee. A greenhorn, and he’s already got a warrior’s name, and what a name! Well, when Sam Hawkens takes a greenhorn in hand, you get results, if I’m not mistaken. Shatterhand. Old Shatterhand.”

Hawkens teaches the greenhorn how to hunt bison, how to rope and ride mustangs, how to read tracks, and how to operate precious guns. Shatterhand is far ahead of his teacher most of the time and surprises Hawkens with his outstanding abilities. [It is also here that] Shatterhand becomes the friend of Winnetou, the young Apache.

For Karl May, Shatterhand was not only a literary character: Shatterhand was his alter ego—the man he wanted to be. In a letter dated April 15, 1897, he wrote to one of his readers: “I am really Old Shatterhand, Kara Ben Nemsi (Karl, son of the Germans), and have experienced everything that I tell.” For this total identification with the persona, he was celebrated by his fans. His character was supported by personal promotional photographs, newspaper accounts, personal letters, and public lectures. The interplay of exotic study, research, and very fine interwoven comments in his novels blurred the lines between imagination and reality.

But the mixture of fact and fiction in public is a dangerous cocktail. Celebrities today face this challenge, too. At the end of his life, May wanted to be understood as a “hakawati,” the Arabic word for storyteller. His real life is the outstanding story of a man who believed in his dreams and who worked hard for his mission. But, it was a long way to fame and glory.

About the author

André Koehler is the Director of Public Relations at the Karl-May-Museum in Dresden-Radebeul, Germany, and holds a degree in tourism marketing from Hochschule Harz University of Applied Science in Wernigerode, Germany. He received one of the Center’s Cody Institute for Western American Studies (CIWAS) fellowships in 2010 where he researched the life and personality of William Frederick Cody from the perspective of Cody’s marketing and public relations qualities as a public entertainer and promoter of different kinds of businesses.

Karl May’s Life, 1842–1912

1842–1855: Birth and childhood

Karl Friedrich May is born into an impoverished weaving family on February 25, 1842, in Ernstthal, a small city within the Schönburg-Hinterglauchau county in Germany. He is the fifth of fourteen children—nine of whom died because of the poor living conditions. His childhood in Hohenstein-Ernstthal in Saxony is not quite what one would call happy. Poverty, worries, financial plight, and social misery permeate the community as well as his family.

1856–1862: Teen years

May receives formal training as a teacher, but his first job assignments in Glauchau and Chemnitz end quickly amid accusations that he was having an affair with a married woman and that he stole a pocket-clock from a roommate. Finally, May ends up in prison for six weeks, losing his teacher’s license.

1863–1874: Strolling through life

Driven by desperation and unable to earn a living as a teacher, May strolls through life playing different roles. For instance, at one time he is a kind of tramp. He dresses up as “Polizeileutnat von Wolframsdorf” (police lieutenant) and secures counterfeit money—which turns out not to be counterfeit money at all. He impersonates one Dr. Heilig, a physician who writes prescriptions, which he was not allowed to do, of course. He dresses up at a store with a brand new, expensive coat, leaving the store without paying the bill. What was the result of these and other real adventures? More than seven years in prison.

1875–1891: A writer emerges

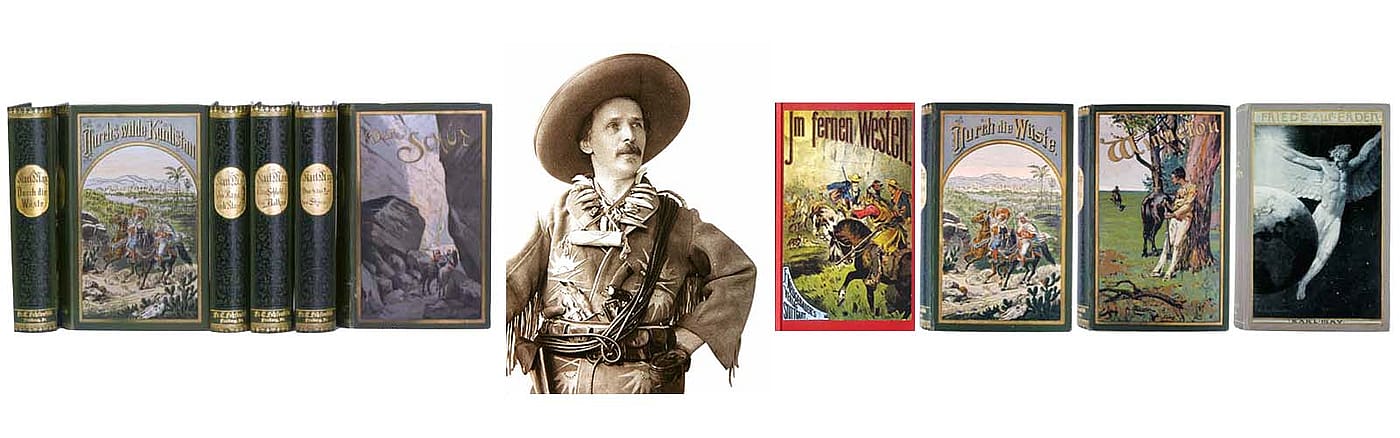

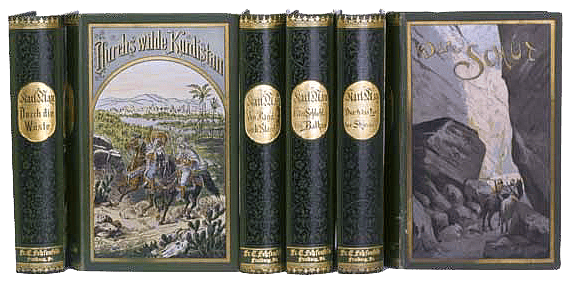

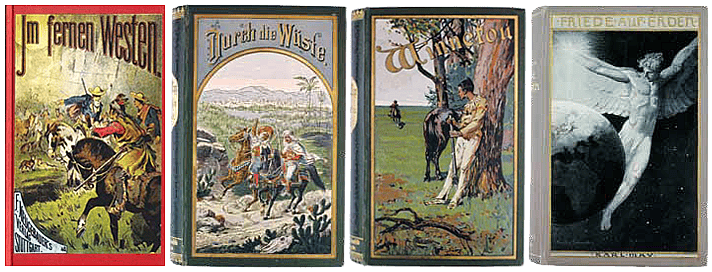

May moves to the city of Dresden were he works as an editor for the Münchmeyer publishing house. Eager to work hard for a new life, he discovers his ability to write fantastic, exotic stories, and in 1879, his first book, Im Fernen Westen (In the Far West), appears. After that, he is able to freelance for well-known German magazines such as Deutscher Hausschatz (German Treasure House) and Der Gute Kamerad (The Good Comrade).

1892–1898: Travel with May

The first volume of Karl May’s “Collected Travel Novels,” Durch Wüste und Harem (In the Desert and Harem), appears in 1892. Five more volumes, the so-called “Orient-Zyklus,” mark the beginning of a phenomenon in German literature. May writes elaborate travel-adventure narratives about the Ottoman Empire, where his main character is Kara Ben Nemsi (“Karl, son of the Germans”). In 1893, three volumes of Winnetou–The Red Gentleman continue the Karl May series, which will be renamed in travel accounts in 1896. May starts proclaiming to be Old Shatterhand himself and rises in public awareness, gaining fame as a celebrity. He not only writes, but travels to give public lectures—all of which make him a wealthy man. Now he has the resources to travel abroad, see the world, and easily pay for Shatterhand’s new villa.

1899–1912: Travel ends

For more than sixteen months, May travels throughout the Middle East, visiting the pyramids of Egypt, as well as Lebanon, Palestine, and Syria. The city of Istanbul and the Acropolis in Athens are on his itinerary, as are Ceylon and Sumatra. However, seeing the real world causes deep depression in May, what can be described as a turnaround of his personality. From that point, he never again plays Ben Nemsi or Shatterhand, and he starts all over with new writing intentions.

May’s later works are deeply symbolic and pacifistic tales. Und Frieden auf Erden! (And Peace on Earth!) is not only the title of volume number 30, but part of his vision, too. In 1908, he crosses the Atlantic for his only journey to America and visits New York, Albany, Buffalo, Lawrence, and Boston—stops on his itinerary that are pulled straight from the Baedeker Travel Guide. He doesn’t see the pueblos of the Southwest or the prairies of the Far West that he had described so vividly before, based on literature of his library and his own fantasy. Copyright disputes and accusations of his opponents regarding his early life are topics at the court and run through the last decade of May’s life.

May dies March 30, 1912, in Radebeul at his Villa Shatterhand. He is buried in a monument at the cemetery Radebeul-East—to this day, a destination for pilgrimages still.

Post 262

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.