Out West with Buffalo Bill – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Summer 2012

Out West with Buffalo Bill: Rosa Bonheur and Oscar Wilde

By Gregory Hinton

There were poets like Whitman and Stevenson, writers from Alcott to Twain, composers such as Verdi and Tchaikovsky, and artists from Monet to Bierstadt. Alexander Graham Bell created his telephone, and Thomas Edison developed the electric light. It was the nineteenth century, and galloping full speed into the thick of things was William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody with his Wild West show. Looking at this myriad of his contemporaries, one catches a glimpse of the life and times of the “Great Showman,” arguably one of the most famous celebrities in the world at the time.

In the story that follows, writer Gregory Hinton focuses on two of those contemporaries—artist Rosa Bonheur and writer Oscar Wilde—and how they came to know William F. Cody. Clearly, accepting the lifestyles of Bonheur and Wilde was not a problem for Buffalo Bill, a man known for his fair and non-judgmental treatment of people, both within and without his Wild West.

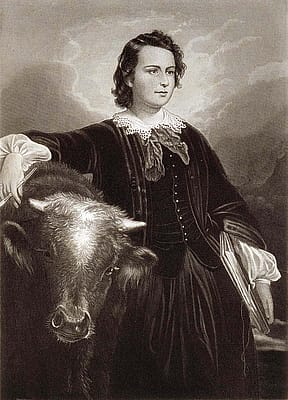

Rosa Bonheur

Rosa Bonheur came from simple but artistic roots. Her father was a painter and her mother a musician, which informed the artistic abilities of Rosa and her siblings. Whenever her father came into extra money, he would toss a few coins to the far corners of his hectic studio. When finances predictably grew tight, she scavenged under paints and old canvases to recover them.

Her beloved mother died very young, and from then on, it would be a man’s world with which Rosa had to reckon. Her talent blossomed quickly, and her reputation as an “eccentric” who dressed in men’s clothing was also well-known. She excused her need for masculine attire as necessary in order to research her chosen subject matter in slaughterhouses and stockyards.

Rosa eventually applied for and received an official permit from the French government to dress like a man—renewable every six months—as long as she didn’t appear that way in public. Her preference for masculine clothing would remain a life-long obsession of the international press.

She and Nathalie Micas were inseparable since Rosa was 14 years of age. They were so close in fact, that on his death bed, Nathalie’s father begged them to never part. As Rosa’s fortunes improved, she bought a castle at By on the edge of Fontainebleau, France, where the two women lived with a menagerie of farm animals, dogs, cats, and birds. Also in residence was a tamed lioness named Fathma.

Nathalie ran the household, managed their business affairs, and served as Rosa’s studio assistant. When visitors arrived unannounced at By, Rosa, dressed to paint, was often mistaken as a handyman when she answered the gate. Nathalie learned to keep a long skirt at the ready near the door, in case a royal carriage appeared.

On one such day, the Empress Eugenie of France arrived and awarded Rosa the Cross of the Legion of Honor—the first woman artist ever to receive such a high accolade. The progressive wife of Napoleon III (out of the country at the time) wanted to underscore her belief that “genius has no sex.”

Nathalie fancied herself an inventor. She created a railroad brake system and tested it on a miniature train with volunteer riders. It failed on a downhill run, tossing “several good ladies” off the grass and into the air. She was “naturally tragic” and gave off airs which amused the dowdy and humble Rosa. They often traveled together, and when Nathalie died in 1889, her devastated friend wrote to another:

You can very well understand how hard it is to be separated from a friend like my Nathalie, whom I loved more and more as we advanced in life; for she had borne with me the mortifications and stupidities inflicted on us by the silly, ignorant, low-minded people. She alone knew me, and I, her only friend, knew what she was worth.

Even before the notoriety of Buffalo Bill, Rosa possessed a keen interest in the American West, sparked by George Catlin’s 1845 visit to Paris with his troupe of Iowa Indians. She later owned an edition of his lithographic album of twenty-five plates called Catlin’s North American Indian Portfolio. “I have a veritable passion, you know, for this unfortunate race,” she said, “and I deplore that it is disappearing before the White usurpers.”

Consequently, in an attempt to re-engage her from the depths of her loss of Nathalie, Rosa’s art dealer arranged for her to visit Buffalo Bill’s Wild West at the 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle in the shadow of the new Eiffel Tower. Cody was no stranger to the artist and in 1896, had even positioned two hundred Percheron and Norman horses into his Wild West arena as a living “tableau” of The Horse Fair, one of Rosa Bonheur’s most famous paintings.

In addition to finding a great new friend in William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody, she also found herself as artist-in-residence behind the scenes of the Wild West. She completed seventeen paintings, including Mounted Indians Carrying Spears (Rocky Bear and Red Shirt) which now hangs in the Whitney Western Art Museum at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West.

Rosa freely roamed the premises, and, especially interested in the Indians, said, “Observing them at close range really refreshed my sad old mind. I was free to work among the redskins, drawing and painting them with their horses, weapons, camps, and animals…Buffalo Bill was extremely good to me.”

And to repay Cody, she invited him to lunch and offered to paint his portrait for free—unheard of since she rarely painted equestrian portraits, and at the time, her works sold for 300,000 francs (nearly $60,000) or more. When the painting was finished, Cody sent it to North Platte, Nebraska, where, a year later, his house caught fire. He wired his sister Julia, imploring her to save the Bonheur, and let the house go to blazes.

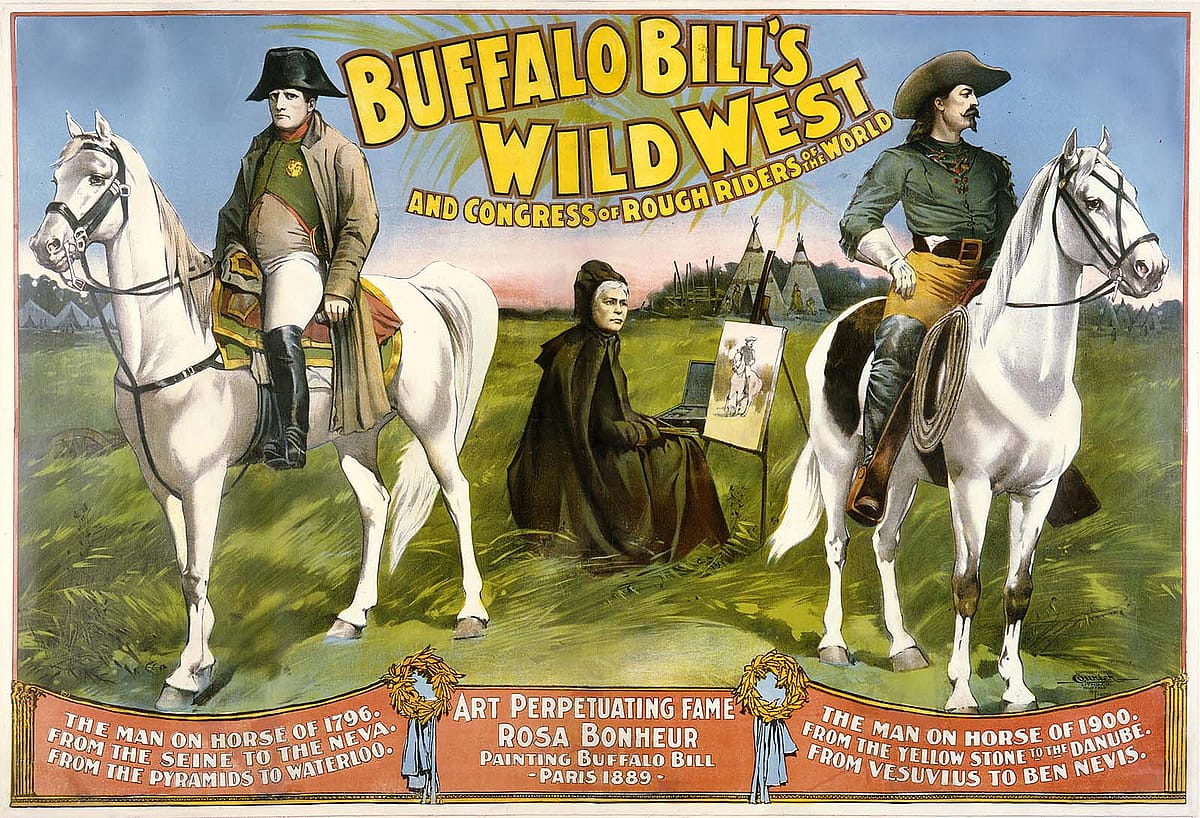

Over the years, the artist’s Col. William F. Cody, 1889, was incorporated into countless posters and programs, including the famous Napoleon, Bonheur and Buffalo Bill, 1896, depicting a seated Rosa between paintings of Cody and Napoleon, each on horseback. This image also served to elevate Cody to the status of a great general. Copies of Rosa’s painting were eventually reproduced by artist Robert Lindneux, who gracefully aged Cody by several years.

Three days after Rosa invited Cody to lunch at By, John Arbuckle, president of the Royal Horse Association, paid a visit. He arrived accompanied by the young American artist Anna Klumpke, who offered to act as translator. Several years before, Arbuckle, a devoted fan of Rosa’s work, had sent a wild mustang from his Wyoming ranch to France for the artist to paint. She was forced to admit that it was too wild to sufficiently stand still, and only days before she had given it to Buffalo Bill. As it happened, a cowboy from his team had easily broken it, and the mustang was now appearing in Cody’s Wild West!

An amused Arbuckle departed, but Anna, whose work Rosa admired, corresponded with the French painter over the years. She later found herself ensconced at By as Rosa’s new companion. When Rosa died shortly thereafter in 1899, her entire fortune was left to Anna, to the exclusion of the rest of the family who had long resented her relationship with Nathalie Micas.

Anna was drafted as Rosa’s chosen biographer, and she went on to enjoy a successful painting career of her own. Commemorating Rosa’s one-hundredth birthday, Anna donated her first portrait of Rosa Bonheur— proudly sporting her Legion of Honor medal—to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Upon her death, Anna’s ashes were entombed with the remains of Rosa Bonheur and Nathalie Micas in Pere Lachaise Cemetery in Paris—Anna having first been assured beforehand by Rosa that Nathalie wouldn’t be jealous.

Rosa Bonheur’s reputation as an internationally acclaimed animalier was well known, primarily as the result of The Horse Fair, reproduced in lithographs all over the world. Wealthy New York entrepreneur Cornelius Vanderbilt eventually purchased the painting for $55,000, donating it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1887. At the time, his daughter, sculptor Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, was only 12 years old. It would be hard to believe that the Rosa Bonheur gifts escaped her attention. And later, when awarded the commission to sculpt Buffalo Bill–The Scout (1924), Whitney reportedly studied as many images of William F. Cody as she could find. One can’t help but ask: Did she, too, contemplate Rosa’s beautiful little painting of Buffalo Bill?

Indeed, of all the artistic renderings of William F. Cody, the Rosa Bonheur painting and the Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney sculpture are among the most iconic, and deservedly so…

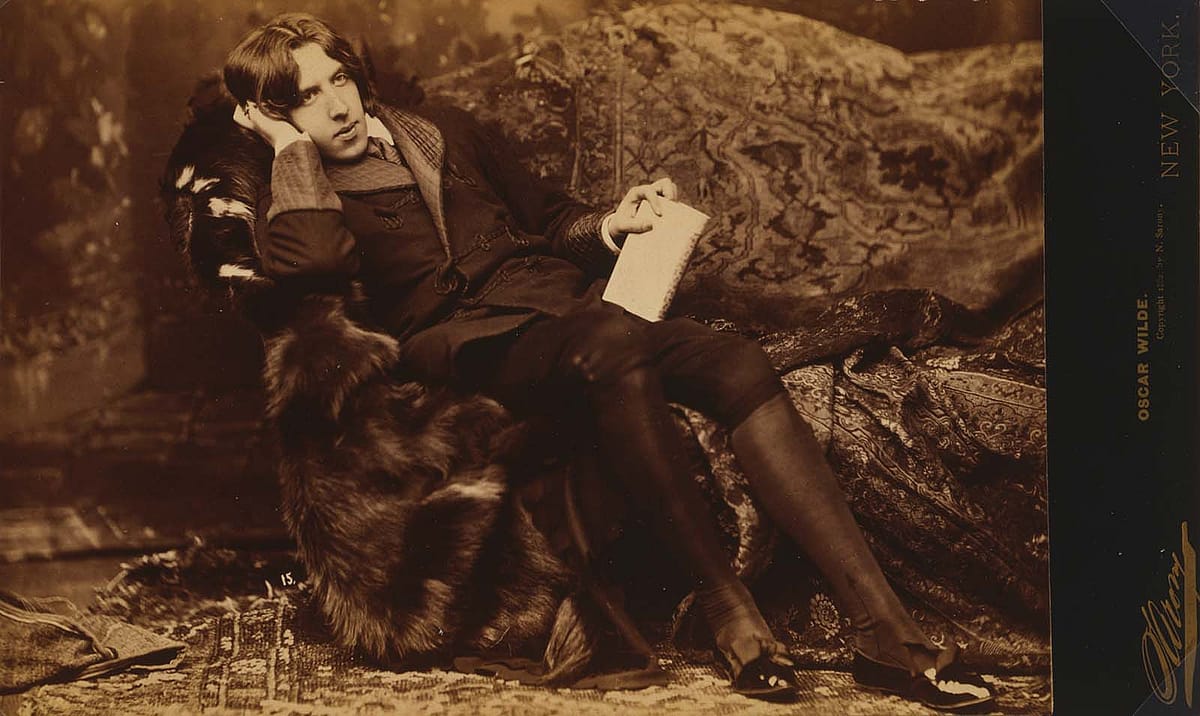

Oscar Wilde

On April 10, 1882, the following missive was sent to the Denver Daily Times from a dusty train car in Cheyenne:

I am told that Denver is a bad place and that some mischievous boys may make it hot for me. If this be true, I will bid farewell to my vow of peace. I am resolved to no longer tamely submit to being made a target for rude youngsters to shy things at. Having shown Americans what gentleness is, I am now determined to defend myself should circumstances so demand it of me. I am practicing with my new revolver by shooting at sparrows on telegraph wires from my car. My aim is as lethal as lightning. – O. Wilde

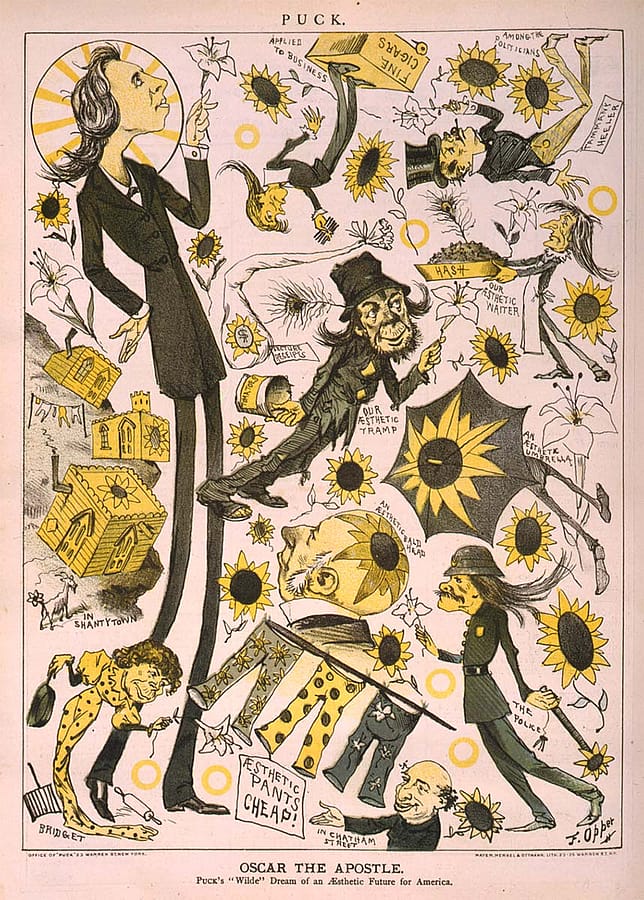

Denver would be the fiftieth among the 150 scheduled cities of the 1882 American tour of poet, playwright, and Oxford scholar Oscar Wilde, lecturing on decorative arts and aestheticism.

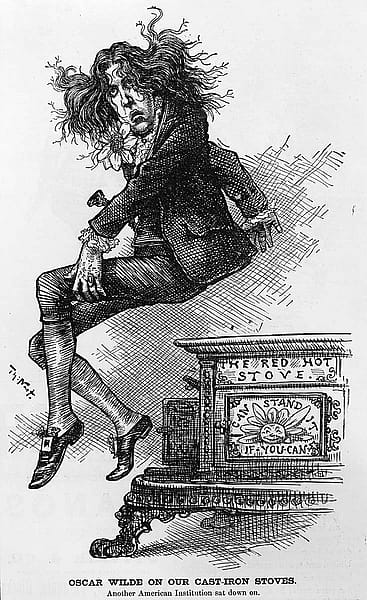

Attired in knee breeches, velvet cloaks, silk stockings, and low boots with buckles, with long flowing hair and a single lily in a vase, this oversized, calculatedly effete Irishman crisscrossed America thousands of miles by train. Oscar twice traversed Wyoming three years before the arrival of The Virginian‘s Owen Wister.

Oscar arrived in America preceded by the publication of his acclaimed edition, Poems, and the Gilbert and Sullivan play, Patience, a direct parody of Oscar and aestheticism (i.e. pursuit of beauty). The heavy scrutiny of the American press took him by surprise, commencing with his off-hand observation that the Atlantic Ocean was a “disappointment” with a similar gaffe about Niagara Falls “flowing the wrong way” to follow. For most of the American tour, Wildean commentary was national front-page news.

Packed audiences met Oscar with suspicion, derision, or reluctant respect. Rowdies in Boston and Rochester disrupted his talks, provoking Julia Ward Howe, author of the Battle Hymn of the Republic, to issue a backhanded apologia for having entertained him in her home. “To cut off an offending member of society from its best influence and most humanizing resources is scarcely Christian…” she wrote.

While in America, Oscar made a pilgrimage to Walt Whitman. According to distinguished biographer Richard Ellmann, Whitman openly discussed his homosexuality and kissed Oscar on the mouth.

And if Oscar greeted the prospect of his Denver constituency with concern, imagine his surprise to find the mining town of Leadville among the most welcoming of his stops. Mining king Horace Tabor named a mineshaft “The Oscar” in his honor and dropped him by bucket deep into the pit. Oscar wryly suggested they might include shares in the mine with the honor. To the miners’ great surprise and delight, Oscar lit a cigar, drank all their whisky, and was pronounced a “bully-boy with no glass eye.”

Oscar stressed the importance of supporting local craftsmen and their handicrafts as an application of aesthetic doctrine. He advocated community arts and crafts museums, saying that “the most graceful thing I ever beheld was a miner in a Colorado silver mine driving a new shaft with a hammer; at any moment he might have been transformed into marble or bronze and become noble in art forever.”

In San Francisco, Oscar witnessed a hulking Chinese “navvie” drinking his tea from a delicate painted porcelain cup instead of from the heavy coarse crockery Oscar abhorred. Of American garb, Oscar felt that its wom¬en might emulate the drapery of Greek statuary. America’s most well-dressed men were his beloved Colorado min¬ers with their wide-brimmed hats and flowing cloaks. He said if he “were a young man in this country, the West would have great charms for him.” These firsthand observations docu¬ment Oscar’s true love of the American West.

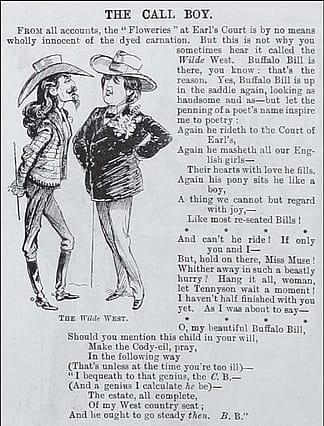

So when Buffalo’s Bill’s Wild West came to London for the Queen’s Golden Jubilee, in his prestigious position as editor of Women’s World, Oscar wrote of “The American Invasion,” saying:

English people are far more interested in American Barbarism than they are in American Civilization…The cities of America are inexpressibly tedious…Better the far west with its grizzly bears and its untamed cowboys, its free open-air and its free open-air manners; its boundless prairie and its boundless mendacity! This is what Buffalo Bill is going to bring to London; and we have no doubt that London will fully appreciate the show!

In 1887, when the Wild West hit London, Oscar had been married for three years and had two young sons. His wife, Constance, was attractive, intelligent, and unprepared for life as Mrs. Oscar Wilde. Her husband spared no expense with his friends, many of whom were single, attractive young men such as Henry James and James Whistler. While Oscar socialized in London, Constance was left to tend to childcare.

Constance was not Oscar’s original choice as a wife. His first proposal went to actress Frances Balcombe, who instead married Bram Stoker, the manager of the Lyceum Theatre at the time. Frances didn’t have it much better than Constance Wilde. Stoker, who ultimately wrote Count Dracula, was deeply obsessed with his boss, Henry Irving, the eminent Victorian actor. Irving saw the Wild West on New York’s Staten Island and befriended William F. Cody before he came to London.

It was on Henry Irving’s arm that Buffalo Bill came to know the British Royals. If Cody enhanced the underwhelming physicality of the actor, Irving, in turn, raised Cody’s credibility mightily above mere circus-master. Some suggest that Bram Stoker may have been jealous of Cody, though it was clear that they had direct dealings.

Invitations by British nobility and upper echelons of the art and theatre world avalanched onto William F. Cody, so much so, that this personal note from Constance implies that Oscar Wilde, too, had to compete for an audience:

Even Lady Wilde, Oscar’s fantastically flamboyant mother[,] sent Cody a standing invitation to her Saturday salon. At the time she was struggling financially, and could not afford help, Speranza [Lady Wilde’s pen name] kept her drapes drawn during the daylight and lit her rooms in red candlelight so no one could see the dust.

When Buffalo Bill took London by storm, Oscar was yet to write his plays, Lady Windermere’s Fan and The Importance of Being Ernest, and his only novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray. His downfall would begin in 1892, when he became seriously involved with Lord Alfred Douglas, the son of the Marquess of Queensbury [of “The Queensbury Rules” of boxing fame]. When Queensbury publicly accused Oscar of sodomy, the writer foolishly sued for libel and lost.

In 1895, Oscar, the toast of London and Leadville, was sentenced to two years hard labor in London’s Pentonville Prison for “extensive corruption of the most hideous kind.” Five years later, he would die penniless in Paris— mostly friendless; not knowing the whereabouts of his sons; preceded in death by his parents, his brother, and poor Constance, too. Oscar Wilde was only 46.

In a review which followed Oscar’s first Colorado lecture, the one warning of Denver’s “mischievous boys,” a Times editor, obsessed with Oscar’s awkward girth and mode of dress, presciently forebode that “…Oscar Wilde was intended for manual hard labor instead of the impractical search for the beautiful.”

About the author

A 2011–2012 Resident Fellow of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Gregory Hinton is the creator of Out West, a historic educational program series dedicated to telling all the complex stories of the American West. Believing western art museums to be safe places to have related complex conversations, Hinton also partners with the Autry National Center in Los Angeles and the Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art in Indianapolis.

Post 271

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.