Specimen Preparation: Everything You Need To Know

Note: Some of the photos included in this post show specimen preparation and might be graphic to some readers.

What is a specimen?

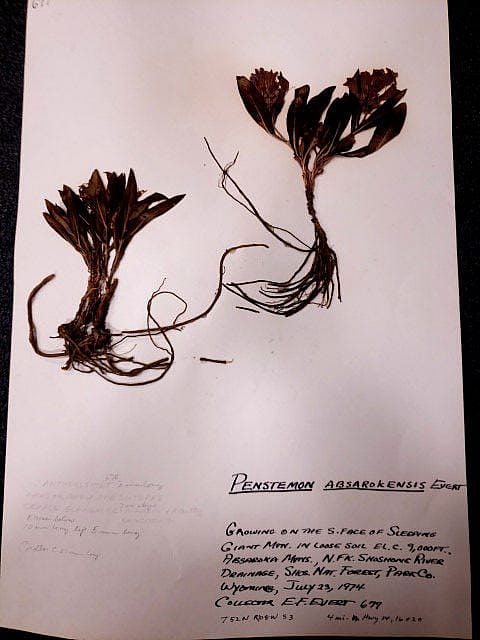

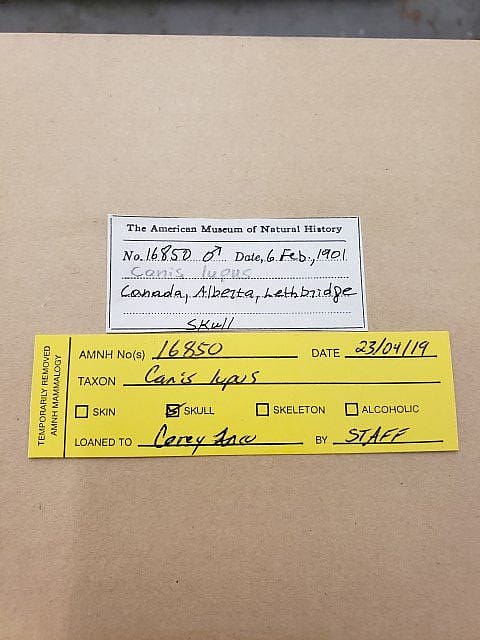

The term ‘specimen’ refers to any object (animal, plant, or non-living) that is preserved for scientific use. Specimens can include skeletons, skins, flowers, minerals, etc and can be whole or incomplete. Most specimens in the Draper Natural History Museum (Draper) have metadata associated with the object including information regarding the origin, species/type, collection date, collector, and sometimes measurements. These data help provide context to researchers studying specific species or systems.

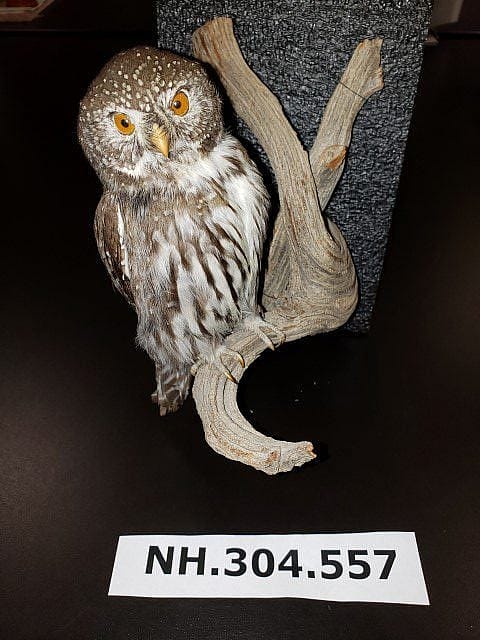

Right: Glaucidium gnoma – Northern Pygmy Owl, Draper Natural History Museum, Buffalo Bill Center of the West

How do museums acquire specimens?

Natural history collections preserve a physical record of the history of life on Earth. Traditionally, collections were developed by taking voucher specimens from nature. As you can imagine, removing large numbers of a species from a given ecosystem can have significant negative impacts on local populations and potentially, the conservation status of a species. Many natural history collections contain large donations from private collectors. Today, museums try to minimize impacting populations, species, and overall, biodiversity. However, museums can still build up significant collections by establishing partnerships with wildlife management agencies.

How does the Draper acquire specimens?

The Draper primarily maintains a salvage-based collection*. This means we do not actively go out and collect specimens from nature. The Draper works with state and federal wildlife managers as well as local non-profits to acquire the specimens in our collection. If an animal is poached or removed from the wild (e.g., for reasons pertaining to human safety), agencies like the US Fish and Wildlife Service and Wyoming Game and Fish Department will transfer the specimen to the Draper. This partnership serves two purposes: 1) it builds cross-disciplinary and inter-institutional relationships among wildlife managers, researchers, and educators; and 2) preserving the animal as a specimen provides value to that organism beyond life.

Wildlife removed from nature through an active management decision have two fates: Find a home or dispose of the carcass. Preserving the skeleton and skins of animals as specimens gives value and meaning to organisms beyond life. Specimens also enable downstream research and programmatic efforts (e.g., morphology, articulation, genetic analyses, etc.).

*Do not handle an injured or dead animal. Please refer to end of this document if you encounter an injured or dead animal and wish to contact the museum.

What kinds of specimens does the Draper prepare?

The Draper primarily prepares bird and mammal specimens from the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Having a specific geographic focus helps us to limit our collection to relevant species while maximizing the use of limited storage space. Bird specimens are typically prepared in two ways: flat and round study skins. In a flat skin preparation, the skeleton is removed with the exception of one wing and one leg, which is left with the skin. The skin is laid flat and the intact wind is spread to show the morphology and feather of the organism. In a round skin preparation, the skeleton of the bird is removed but both legs and wings are left attached to the specimen. Additionally, the beak and a small portion of the skull is left attached to the skin. The body cavity is then filled with cotton and the specimen is sutured together.

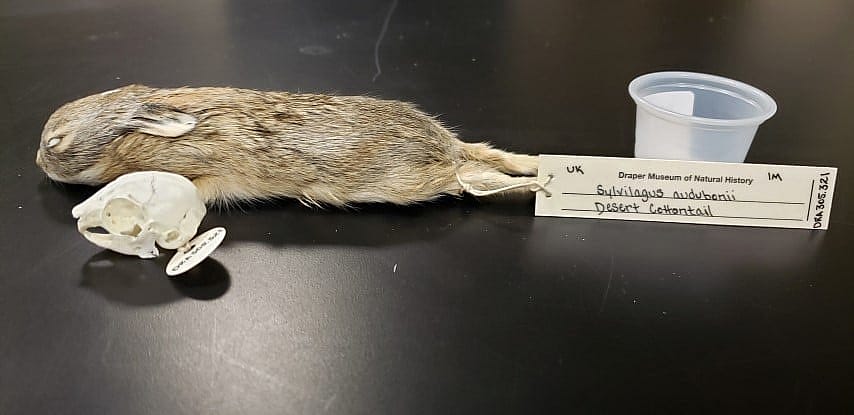

Smaller mammals are skeletonized while the skin is prepared as a body mount. With most larger mammals only the skull is prepared. Space restrictions prohibit retaining the entire skeleton of some species.

Right: Study skin and skull of an immature desert cottontail

Why do natural history museums like the Draper maintain a collection of specimens?

Museum collections are invaluable to researchers and natural history museums are increasingly becoming the only institutions to document and retain physical records of the history of life on Earth. When a species or population is no longer documented or has become extinct where it was once found, museum specimens may be the only physical record of their existence. Thus, specimens are ‘snapshots in time’.

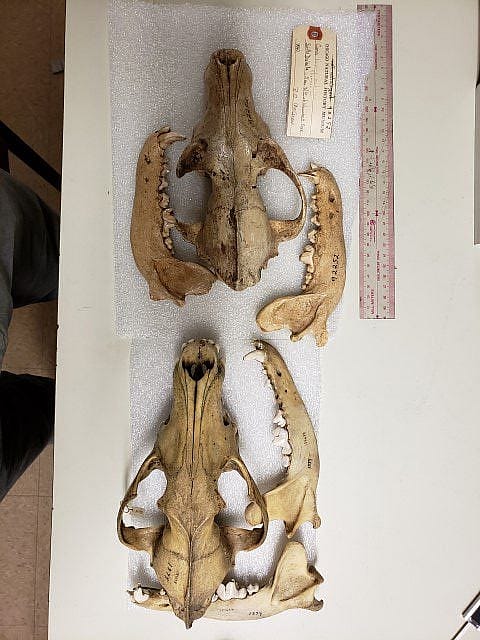

The Draper maintains specimens representing the diversity of fauna and flora (biodiversity or biological diversity) found in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE). We are the only major repository in the region dedicated to acquiring and maintaining scientific collections, especially of higher vertebrates, inhabiting the GYE. Comparative anatomy is a fundamental skill used to distinguish organisms in natural history museums. When identifying an unknown or unidentified specimen, researchers reference museums holotypes, or the individual specimen upon which a species is named or described. These specimens thus become essential reference material to aid collections-based research efforts.

Draper specimens represent a significant research and reference collection primarily of higher vertebrates. Researching natural history collections provides important contributions to science and increases our knowledge and understanding of the natural world.

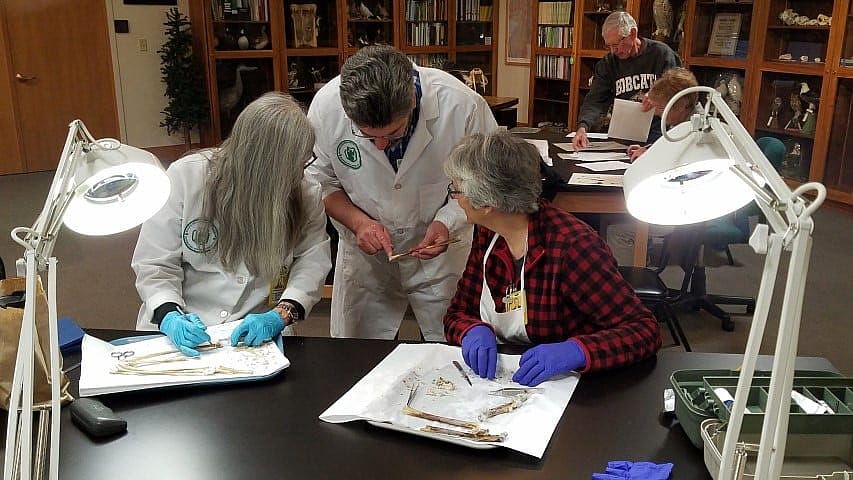

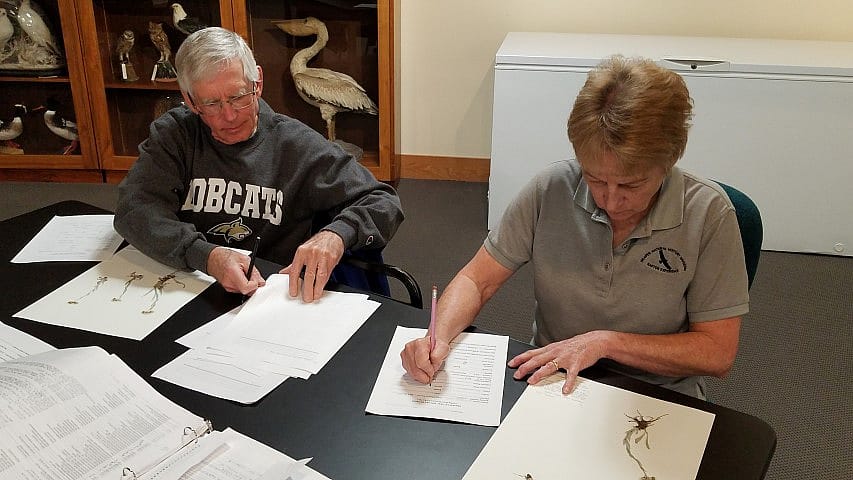

Who prepares specimens?

Draper collections are developed by staff and a small, but dedicated army of volunteers affectionately called the ‘Draper Lab Rats’. Volunteers do everything from specimen preparation, labeling, photographing, cataloging, and more. Put simply, the Draper collections would not exist without our incredible and energetic volunteers!

Can I watch staff and volunteers prepare specimens?

The Draper Discovery Lab is equipped with large ‘view in’ windows where you can watch staff and volunteers actively preparing specimens. Visit the Draper Lab on a Tuesday morning between 9:00 AM and 12:00 PM MDT to catch us working on specimens!

How do you prepare a skeleton?

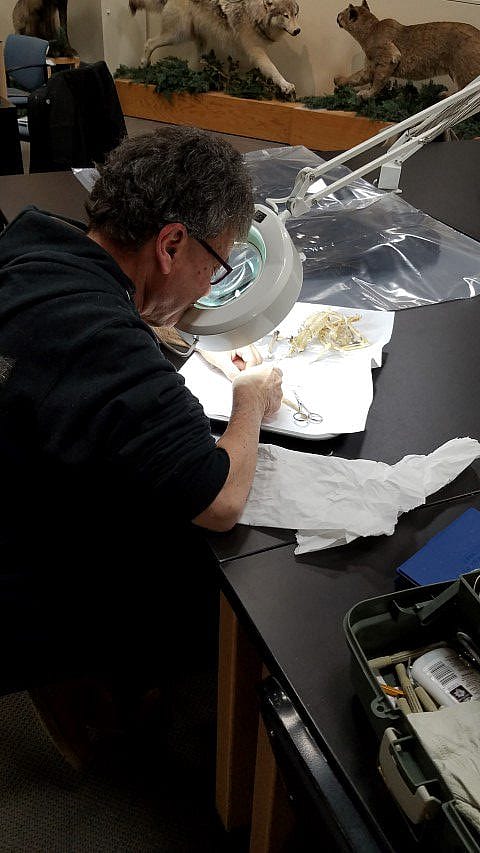

Specimen preparation is a multi-step process. When the Draper acquires an organism, it is frozen until we can assign a preparator. The organism is then thawed and the preparator makes a carefully placed incision depending on the preparation method used for that organism. The goal of the preparator is to extract the skeleton and remove as much muscle tissue as possible to aid the skeletonization process.

Once most muscle tissue has been removed, the skeleton is placed into a terrarium with dermestid beetles. The beetles consume the remaining muscle tissue and once finished, leave a completely skeletonized carcass behind.

What are dermestid beetles?

Dermestid beetles are part of a larger group of invertebrates that includes detritivores, or organisms that feed on decaying or dead remains. Dermestids are commonly found throughout the world, and the family, Dermestidae, includes approximately 700 species! These small organisms (adults are typically 2-5 mm in length) reach very tight spaces and do an excellent job at cleaning very hard to reach places within a skull or skeleton.

How long can dermestid beetles live?

Dermestid beetles typically live about 4-5 months. Dermestids develop within eggs for about 4 days before hatching as larvae. Larvae can be very tiny, comparable to the size of a pinhead, and molt approximately 7-9 times over the course of 5-6 weeks before they reach a stage where they seek shelter to pupate. After about 7-8 days, the pupae emerge as an adult beetle. Adult female beetles lay eggs after about 2 months and the cycle repeats so long as the colony has sufficient food and stable living conditions.

How long does it take to skeletonize a specimen?

The size of the skeleton, number of bugs in the colony, temperature and humidity conditions all play a factor in the amount of time it takes to clean a skeleton. Before a skeleton is placed in the beetle colony we try to remove as much soft tissue as possible. This allows the beetles to focus ‘cleaning efforts’ on more difficult to reach places. Beetles thrive between 70-80 degrees Fahrenheit and prefer fairly humid climates, usually between 50-60%. A climate stable facility increases efficiency and reproduction of the beetle colony, which expedites the time needed to effectively clean a skeleton. A thriving colony can clean a songbird skeleton in a few hours to a day (depending on conditions), whereas a larger bodied organism (e.g., a wolf or bear) could take days to weeks. For larger bodied organisms we segment the skeleton and feed the beetles smaller sections of the skeleton at a time. This reduces the likelihood of soft tissue drying out or rotting before the beetles have a chance to finish cleaning.

Do you use chemicals?

The Draper uses two very diluted solutions to aid in the preparation of skeletons. Once a skeleton is removed from the beetle colony it is frozen to prevent any hitchhikers from exploring the museum. The skeleton is then thawed after a minimum of 72 hours, and placed in a solution of ammonia and water. The ammonia solution helps to ‘degrease’ the skeleton. The skeleton is then placed in a solution of hydrogen peroxide. This solution helps to gently whiten the bones.

I’ve heard boiling skulls is a common way to clean them, should I use this method?

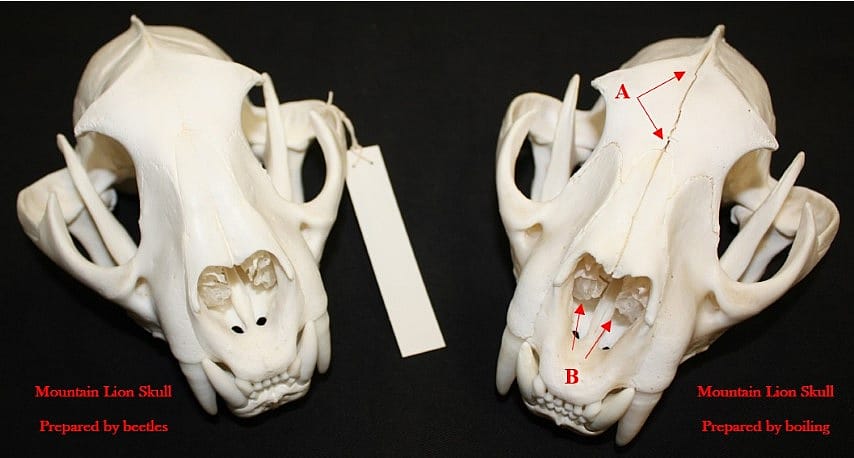

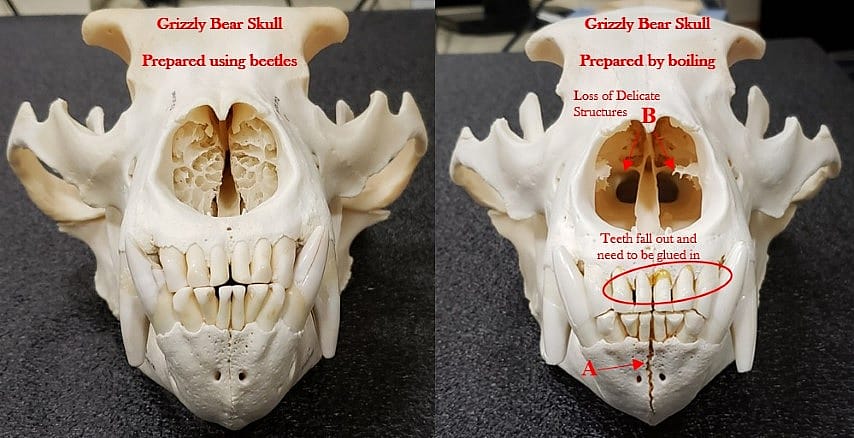

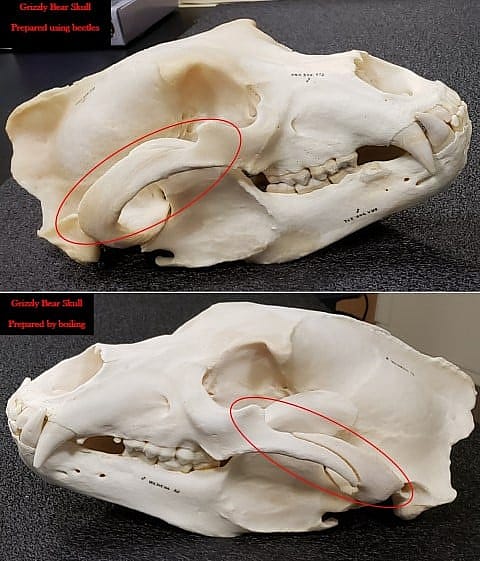

Boiling skulls is a method many places use to loosen and remove flesh and connective tissue. While cost effective, this method has several negative impacts which affect the quality of the skeleton or skull. Submerging a skull in boiling water subjects the bone structure to intense changes in temperature and pressure. This rapid change damages sensitive structures within the skull and can cause fracturing and splitting of the teeth and bone sutures. As a natural history museum, our goal is to preserve the integrity of the specimen to the best of our ability. While our preparation process is lengthier than boiling a skull, it does the best job of preserving the original integrity of the specimen.

The skulls on the left were prepared using a dermestid beetle colony. The skulls on the right were prepared by submerging the skulls in boiling water. Boiling skulls can compromise the integrity of the skull for research, destroy fragile structures, weaken sutures, and crack teeth. Note (A) the stress fractures along the skull sutures, (B) damaged turbinates or nasal conchae of the boiled skull.

The grizzly bear skull on top was prepared using a dermestid beetle colony. The grizzly bear skull on bottom was prepared by submerging the skull in boiling water. Note the separation of the zygomatic arch in the grizzly skull that was boiled.

Will the Draper clean a skull for me?

We are often asked if we will clean skulls. Our policy is to maintain a dermestid beetle colony for the purpose of preparing scientific collections and therefore do not prepare skulls or skeletons for clients. Your local taxidermist likely has or has access to beetles to prepare bones.

What does the museum do with the skins and bones?

The Draper uses specimens in our galleries and exhibits, educational programs, and for research. Skeletons are an excellent tool to teach function and morphology, while examining skeletons and skulls teach us about the life history of the organism – what does it eat? how might it have hunted or gathered food? how did it live? what kinds of unique adaptations does it have? Additionally, bones can be measured, skins studied, and DNA extracted from specimens which helps us ask and answer additional questions about population and species-level diversity of organisms in the Eastern Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

What is in the Draper collections?

The Draper has over 400 mammals, 600 birds, 6000 plant specimens in the natural history collection. This includes more than 150 wolf skulls with a growing inventory of greater Yellowstone carnivores thanks to partnerships with state and federal wildlife managers. Our bird collection includes large numbers of songbirds and raptors thanks to partnerships with local non-profit Ironside Bird Rescue.

I’m a researcher and interested in studying the collections. How can I gain access to the natural history collection?

The Draper and the Buffalo Bill Center of the West is actively working on uploading our collections to global databases. For now, these collections are housed on our internal database, ARGUS. If you are interested in working with our collections please submit an inquiry to [email protected] to obtain an application.

Can I sample the collections?

Yes! The Draper does permit sampling of our collections. For invasive sampling we developed a Destructive Sampling Guideline, which requires researchers to submit an application to [email protected] detailing the extent of the sampling request and expected products of your research.

What should I do if I find a dead or injured animal and want to reach the museum?

Do not handle wildlife. Wildlife can carry disease and handling an injured animal can cause harm to you or further worsen the injury or condition of the wounded animal. If you encounter an animal that appears wounded, contact the appropriate authorities first.

For mammals contact the Wyoming Game and Fish Department – Cody Regional Office 307-527-7125

For birds contact Susan Ahalt of Ironside Bird Rescue 307-527-7027

If the animal is dead and in good condition* (e.g., intact / not mangled) please contact the Draper Natural History Museum Lab at 307-578-4064 and leave a message with the following information:

- Your name

- Contact information

- Description of animal

- Date and Time

- Physical location/coordinates

- Cause of death if known

You can also email [email protected] or [email protected] with photos and the same information.

*As soon as an animal dies the organism begins to decay. Freezing an organism slows this process, however possession of native wildlife without a permit is illegal and prohibited by state and federal laws. Please see Wyoming Game and Fish Department Regulations and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Regulations for more information.

Written By

Corey Anco

Corey Anco is the Willis McDonald, IV Curator of the Draper Natural History Museum. Corey leverages his background and training to advance the role of natural history museums in elevating the public’s understanding and appreciation of science through collections and field-based research and hands-on, inquiry-based programming. In his spare time, Corey can be found cooking, beside a fire with guitar in hand, or backpacking in the mountains.