Don’t Fence Me In: A Draper and Science Kids Adventure

The Future of Wildlife Resides in the Hands of the Youth

That was one of several take home messages that youth participants of the Don’t Fence Me In Science Kids program received over the duration of the 3-day course held in June 2021. In 2019, the Draper Natural History Museum was awarded a grant by the Wyoming Wildlife Foundation, part of the Wyoming Youth for Natural Resources program, which seeks to actively engage youth in the hands-on conservation and science-based management of Wyoming’s natural resources.

The program was originally scheduled for the summer of 2020, however complications associated with Covid-19 led us to reschedule the program for 2021. As health officials relaxed constraints surrounding group activities we carried on with our course.

Fences serve several important functions on the landscape. They delineate property boundaries, prevent domesticated animals from roaming onto highways and properties, and exclude undesired wildlife and sometimes people from entering an area. There are many different fence designs and each of them have advantages and disadvantages. Wildlife and land managers, like the Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Forest Service, and Wyoming Game and Fish Department are tasked with maintaining and evaluating existing fence lines on public lands. Advancements in technology have aided our understanding on how wildlife, and migratory ungulates in particular, navigate through the mosaic of public and private lands that characterize their migration routes. Depending on the design, (e.g., fence height, spacing, materials, and location, etc) a fence could work too well – preventing any wildlife from successfully crossing the fence and reaching their winter/summer ranges.

There is a whole field dedicated to the study and impact of fences known as Fence Ecology where scientists collect empirical data and assess whether a particular fence acts as a barrier to wildlife. Using data from wildlife collars, media from remote cameras, and boots-on-the-ground monitoring – scientists and land managers in Park County, Wyoming are taking a critical eye at the fences that surround us. But making fences wildlife friendly is more than just identifying and modifying fences. It’s also about education. And that’s where working directly with youth and putting the responsibility of managing Wyoming’s wildlife directly into their hands comes into focus.

From May 31 through June 2, 2021, 11 youth, aged 8-12 years old, worked alongside the Bureau of Land Management: Cody Field Office, Wyoming Game and Fish Department, and Draper Natural History Museum to modify a section of fence on public land. In the process, students developed a greater understanding of migration and deeper appreciation for land and resource management in Wyoming.

Meet the Instructors

Nathan Doerr: Curator, Draper Natural History Museum

Corey Anco: Assistant Curator, Draper Natural History Museum

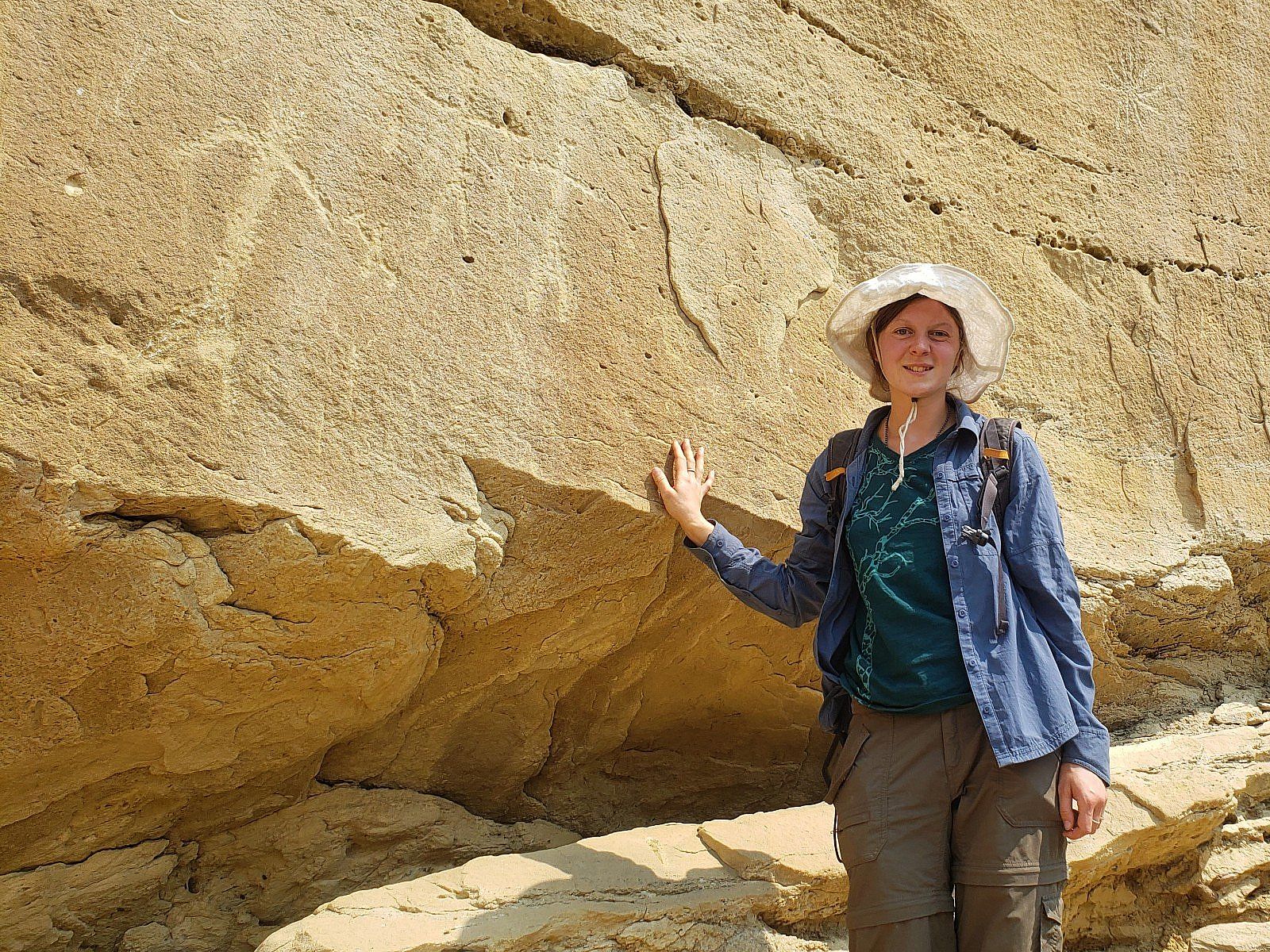

Alexandrea Farquhar: Curatorial Intern, Draper Natural History Museum

Tony Mong: Wildlife Biologist, Wyoming Game and Fish Department

Alicia Hummel: Rangeland Specialist, Bureau of Land Management, Cody Field Office

Adam Stephens: Rangeland Specialist, Bureau of Land Management, Cody Field Office

Destin Harrell: Wildlife Biologist, Bureau of Land Management, Cody Field Office

Larry Oliveria: Assistant Instructor and Driver, Science Kids

Day 1: Migration in the Absarokas

After a quick introduction and ice breaker, students and instructors loaded up in the Science Kids bus and headed 20 miles up the North Fork to the Jim Mountain access road. On the way, students were primed with the first few steps of the Scientific Method. Beginning with an observation, students asked questions about their surroundings: what activities or signs of wildlife did they notice around them? Who might live here? What kinds of habitats and vegetation are here? What is the terrain like? Students were then asked to develop hypotheses, or a possible explanation for their observations and questions.

This exercise intended to move students from purely observing the world around them to inquiring about their observations. Science is a way of thinking about the world that inspires the curious nature residing within each and every one of us. It takes us one step beyond the observation that something interests us and challenges us to ask and answer why does this observation, event, phenomenon strike our curiosity? It is the pursuit of knowledge, not for knowledge sake, but to better understand the incredible world that we live in.

Draper Natural History Museum Curator, Nathan Doerr, led an activity to provide the students with a sense of place. Using colors, textures, and sounds from their environment, students made connections between themselves, physical objects, and the landscape. In doing so, they were asked to employ several senses to observe and generate inquiries of the world around them.

So much of how we experience the world comes from experiencing it through the five basic senses: sight, smell, touch, taste, and sound. By stimulating several of these senses we interact with our environment in a different way. Scientific journaling is an important part of the discovery process. When examining a plant in front of you several obvious features might stand out: flower color, shape of leaves, and height of the plant but when you record all of this information in a notebook you begin to notice the subtle details and the details tend to be where discoveries and connections are made.

Assistant Curator, Corey Anco, turned the students’ attention first to natural features of the North Fork: mountains, valleys, rivers, and cliffs and then to the highway, vehicles, fences, and buildings peppered throughout the landscape. Alterations to the landscape along with some natural features can act as barriers to migration, influencing where and how wildlife like mule deer, pronghorn, and elk move.

Human beings are incredibly adaptable. When we drive the same route everyday we tend to gloss over the nuances and details present in our daily commute. But intentionally calling attention to these details allows us to see the landscape in different ways. At first glance, a relatively large, open landscape like Wapiti Valley might seem unobstructed for migratory wildlife but once you factor in highways and the vehicles that travel up/down them, houses, fences, habitat, natural events (e.g., wildfires), livestock, and waterways then suddenly the amount of unimpacted land accessible to wildlife is drastically reduced. Drive the North Fork highway anytime during migration season and you are more likely than not to observe large herds of elk and mule deer recuperating in farmers’ fields.

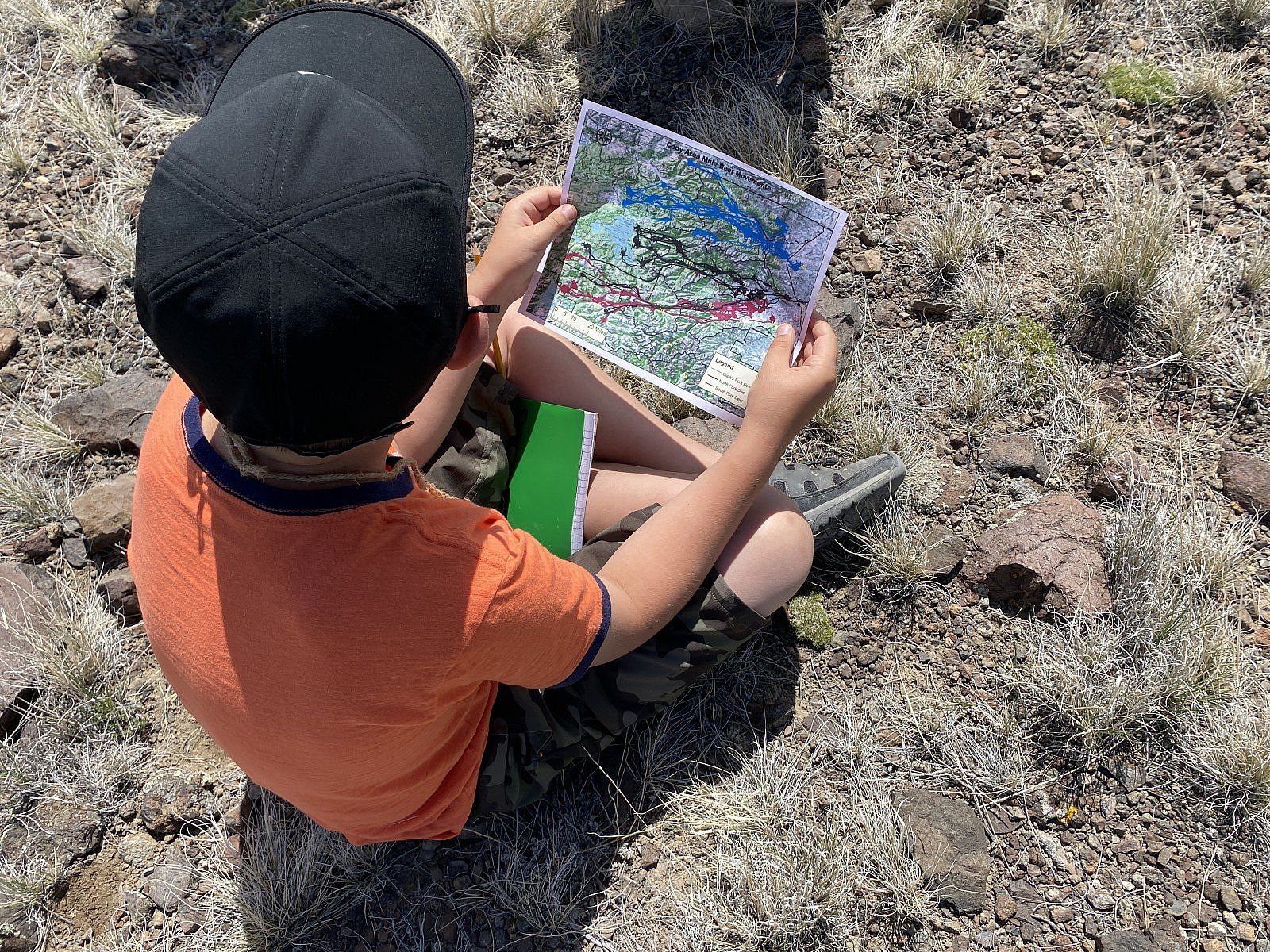

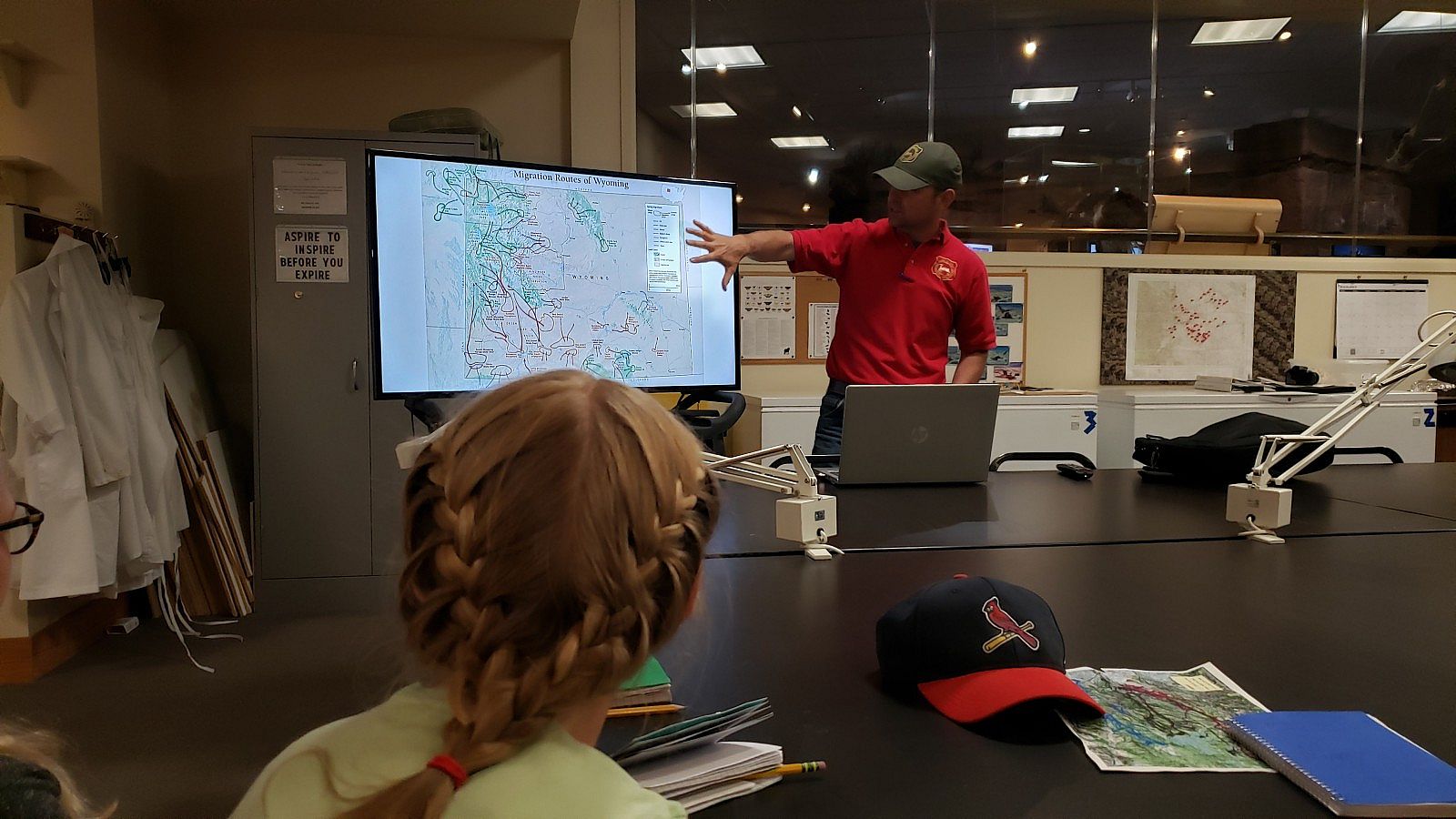

To visualize animal movements and barriers, Wyoming Game and Fish Department Wildlife Biologist, Tony Mong, distributed maps showing the migration routes of deer and elk herds along the North Fork, South Fork, and Clark Fork corridors. Students were also shown how biologists track migration routes through radio and GPS collar data.

Maps help us to visualize the landscape in ways that difficult to see from the ground. Where are wildlife constricted? Do they use the same narrow migration corridor between individuals? What about year to year? The rugged and often unforgiving landscape of the west can act as a funnel, directing wildlife to move through specific areas. Perhaps unsurprisingly, wildlife, like humans, frequently choose the path of least resistance. Migrating between summer and winter ranges can be energetically and physically taxing on an animal. Given the choice between significant and frequent elevation changes and a flat, linear path most wildlife will choose the latter. This is evident from the amount of sign (hair, tracks, scat, etc) observed on hiking trails and you guessed it, fence lines!

Putting everything together

Having visited an actual migration corridor, students returned to the Draper Natural History Museum and put all their knowledge into practice by measuring the distances of actual migration routes on the museum’s tile map. Stretching from the Teton, Absaroka, Beartooth, and Wind River Mountains students calculated the distances pronghorn, deer, and elk travel twice a year in search of habitat and mates. This exercise also helped to contextualize not only the ground covered by some of these animals but also the magnitude of migration routes.

The first day concluded with a presentation by Tony using images of actual wildlife migrations in the Eastern Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Thus, students were introduced to another method (remote cameras) and step of the scientific method – data collection.

Day 2: Boots on the Ground

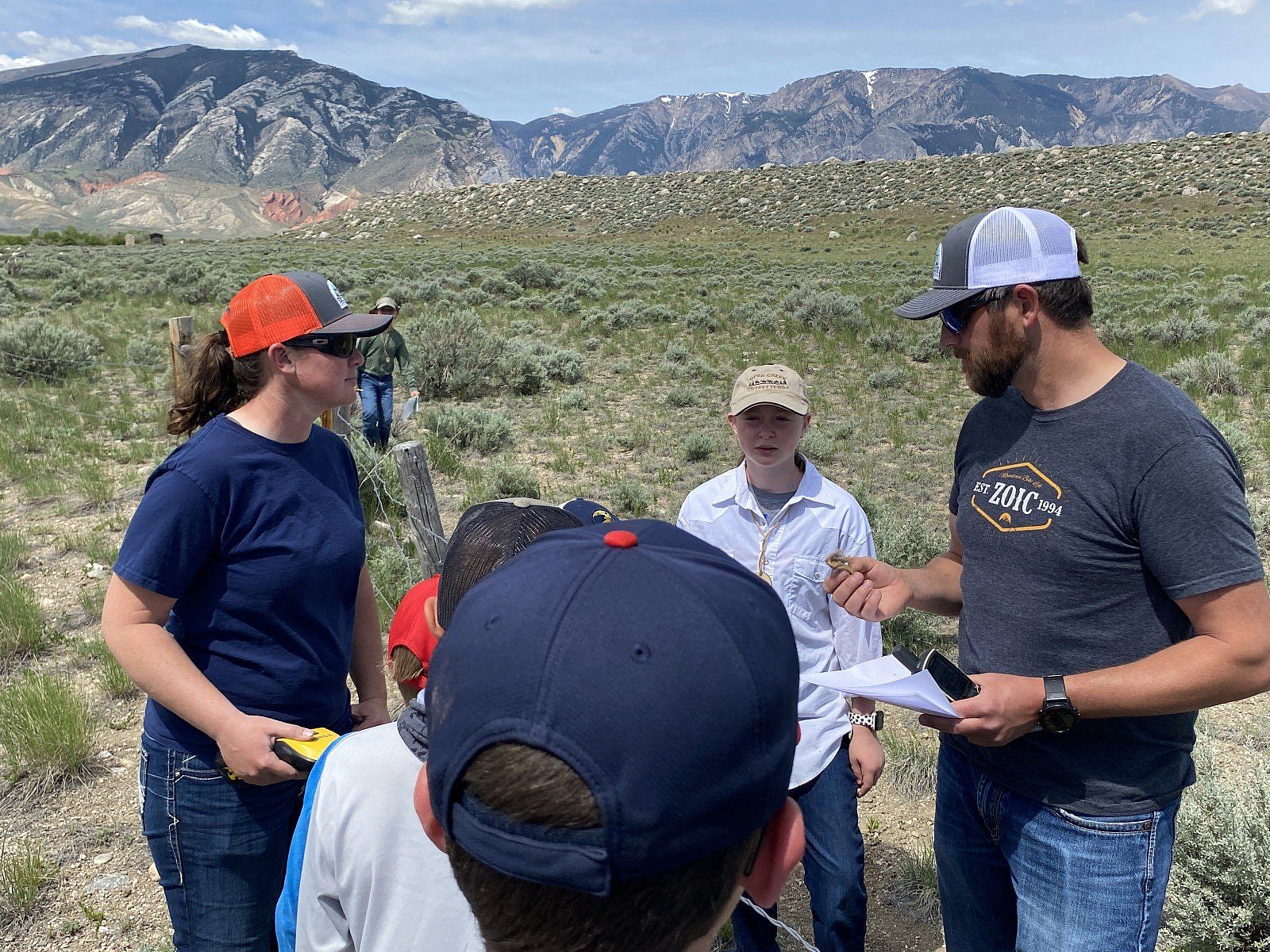

The next day, we took the classroom back into the field driving ~40 miles north of Cody to the Beartooth Ranch. The students were joined by Range Specialists Alicia Hummel and Adam Stephens with the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). Alicia and Adam discussed how the BLM manages multiple use landscapes for wildlife and livestock and played an interactive game with the students to demonstrate fence design (barbed and smooth wire, buck and rail, etc) and allotment systems.

Some species, like pronghorn prefer to go under the bottom strand of a wire fence. This means modifications to the bottom wire of a fence that is barbed and/or too close to the ground will have a positive effect on migrating pronghorn. Other species like mule deer and elk tend to jump over fences. Data has shown that a top wire that does not exceed 42” is permeable for most deer and elk, whereas 16” is the minimum height recommended for the bottom wire. Evaluating whether a fence meets the spacing requirements of a ‘wildlife friendly’ fence is just one component of the job. Alicia and Adam spend countless hours developing relationships with landowners and lessees, monitoring the health of grazed landscapes, and ensuring fences serve their intended purpose without restricting the movement of native wildlife.

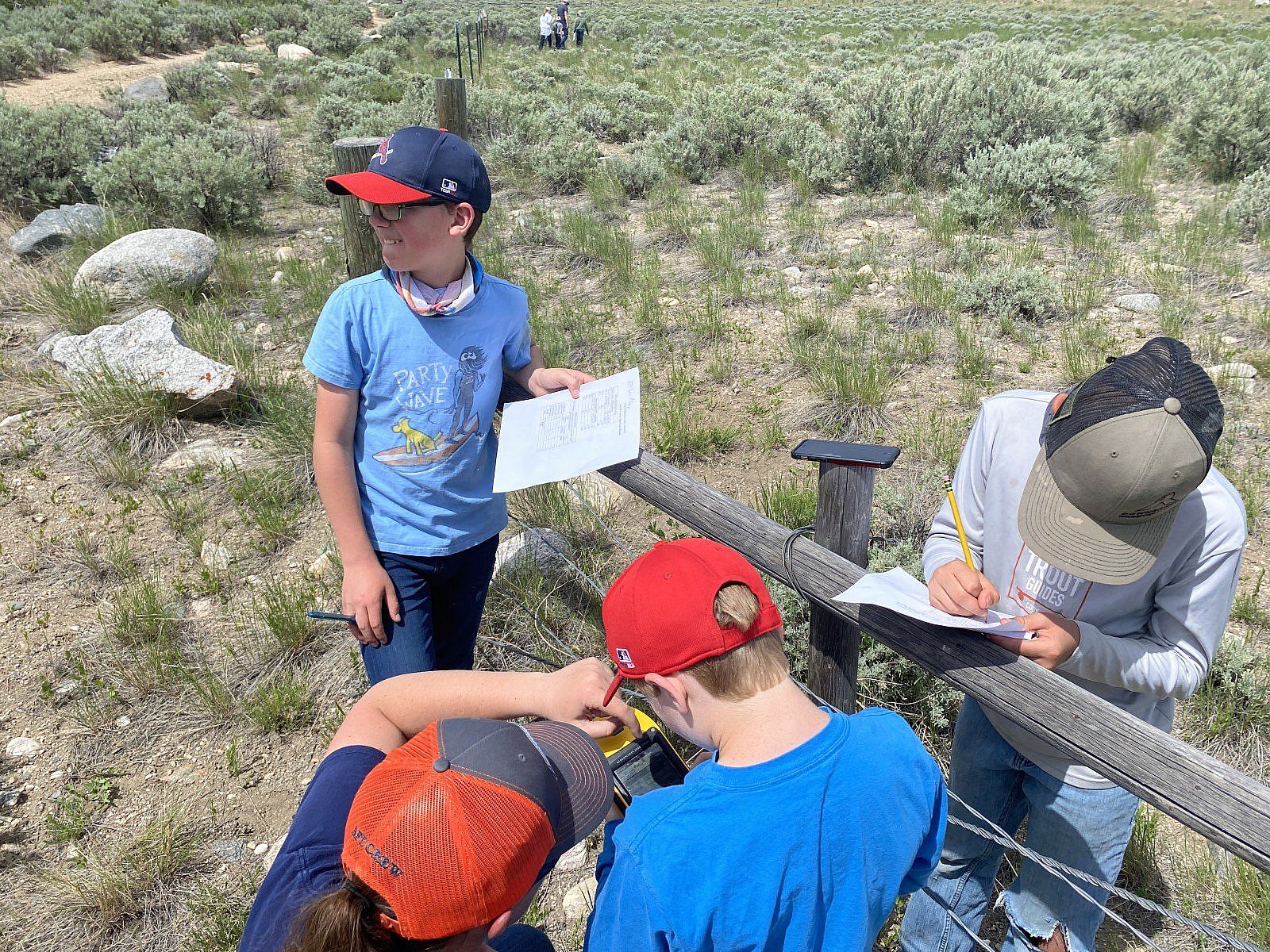

After lunch, the students broke into groups and learned how to document fence lines. Armed with datasheets and GPS units, students recorded the type of fence (buck and rail, barbed, electric, etc), fence corners, and recorded any signs that wildlife may be traveling alongside or crossing the fence. Students observed the tracks of pronghorn running parallel to the fence in search of an opening, the hair of several animals caught fence’s barbs, and plenty of scat. Each of these signs indicate this fence line is frequently visited by migratory ungulates. Not only did the students collect fence line data, they connected the dots as to when a fence modification or removal may be recommended or necessary. Fenced areas that show heavy use by wildlife (tracks, hair, scat, etc) may be important areas for crossing and warrant modification.

Day 3: A Fence to be Reckoned With

On the final day, the students returned to the Beartooth Ranch and worked alongside instructors to remove a section of fence that no longer served a functional purpose. As we turned off the main highway and onto a local road, students witnessed two pronghorn dash in front of the Science Kids bus and beneath a nearby fence separating a pasture from the highway. Once on site, Destin Harrel, Wildlife Biologist with the BLM, led a discussion on safety and use of fencing pliers, before students broke into groups and spread out along the fence line. Working alongside instructors, students removed chicken wire, fence staples and clips, and pulled the downed barbed wire away from the posts for easier retrieval. Destin demonstrated how to use a wire stretcher and students began splicing in a smooth bottom wire. Throughout the day students were kept engaged with themes of migration, fence ecology, and land management.

Len Fortunato, a member of the Beartooth Ranch Advisory Committee, provided historical context for how the Beartooth Ranch came into public hands before rolling up sleeves and diving into fence work. Len also pointed out an active nest of ospreys that called the Clark Fork River home. While our focus may have been on fence ecology these 3-days were more about instilling a scientific curiosity about the world around them.

And connections among wildlife, fences, and the landscape were made. Destin remarked, “the students really demonstrated their ability to develop their own thoughts and assessments of fences and their possible impacts on wildlife after learning the issues.” The instructors helped students detach wire and piled it into the back of BLM trucks. With a long couple days in direct sun under their belts, the students enjoyed a relaxing lunch in the shade and a discussion on careers in wildlife and wildlands management. After lunch, we headed back to Cody. Upon leaving the Beartooth Ranch the students also left behind a positive, tangible impact by removing fence from an important migratory corridor.

Nearly everywhere you look you can see evidence of human impact on the landscape. “These are are the future landowners, policy makers, and wildlife managers” said Anco. Youth programs like this one instill a foundation and understanding of wildlife and resource management in Wyoming. Indeed, the land, the wildlife, and the people that live here are intricately linked to one another. “Understanding what role we play in facilitating the movement of migratory wildlife through fenced landscapes helps us ensure that these resources stay on the landscape to be appreciated and enjoyed by future generations.”

Keep up with the Draper Natural History Museum on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter! Feeling inspired to learn more about fences or want to get involved in local efforts to modify and remove problematic fences in Park County? Check out the Absaroka Fence Initiative’s website and signup for the newsletter to be notified of future public workday events!

Written By

Corey Anco

Corey Anco is the Willis McDonald, IV Curator of the Draper Natural History Museum. Corey leverages his background and training to advance the role of natural history museums in elevating the public’s understanding and appreciation of science through collections and field-based research and hands-on, inquiry-based programming. In his spare time, Corey can be found cooking, beside a fire with guitar in hand, or backpacking in the mountains.