Man of the West, Man of the World, Man of Will – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Fall 2011

Man of the West, Man of the World, Man of Will

By Dr. John C. Rumm

Dr. John Rumm, Curator of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West’s flagship Buffalo Bill Museum at the time of its reinstallation in 2012, thought long and hard about what he personally hoped to portray about William F. Cody in the “new” Buffalo Bill Museum. He would tell you that there’s a marked difference between the person of William F. Cody and the persona of Buffalo Bill, and it’s possible that readers may know one but not the other. Rumm explained further in this article from the archives, first published just before the museum’s July 4, 2012, Grand Re-opening:

“I am American enough to think that we can do almost anything if we once make up our minds that it has to be done.” —William F. Cody, newspaper interview, 1899

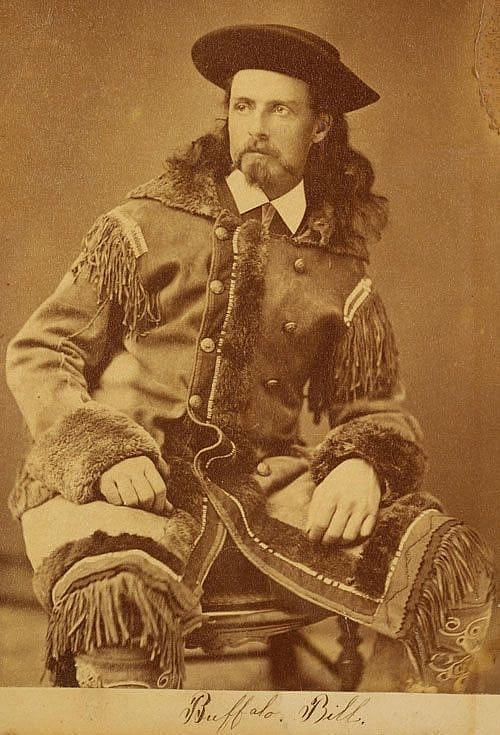

To millions, he was—and still is—known as “Buffalo Bill.” Yet William F. Cody seldom used, and never much cared for, the nickname “Bill.” To his family and close friends, he was always called “Will.”

“Will,” as in purpose. Determination. Resolve.

“Will” as in “I will.”

Cody made this his personal mantra. Asked in 1912, “if all the boys in America were in session, and you [could] telegraph a few words of advice” to them, his reply was characteristically simple and direct: “I can and I will.”

I can and I will.

For Cody, the “Man of the West” who became, almost improbably, the “Man of the World,” no other phrase more aptly summarized his life’s journey or the character that carried him through it.

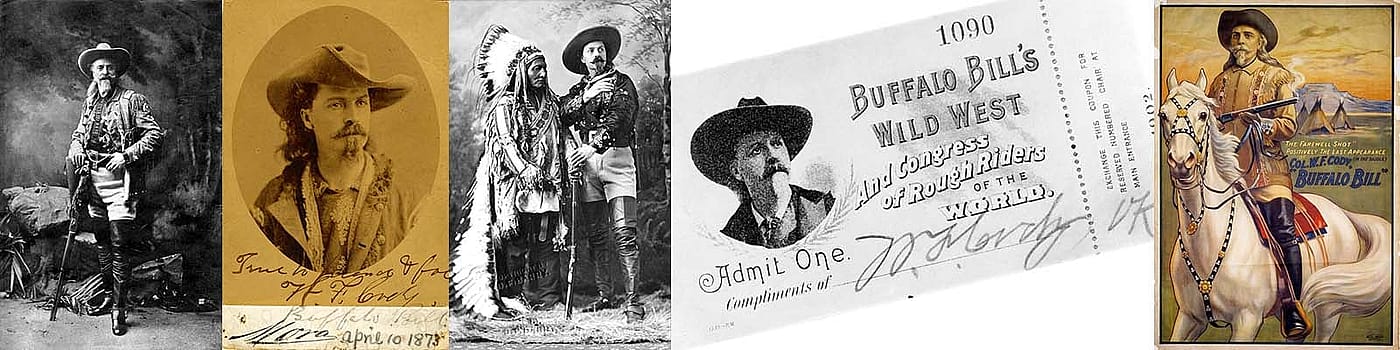

Left fatherless at age 11, Cody began working at frontier occupations to support his mother and sisters. By age 21, he was famed as a guide. Hired to furnish buffalo meat to railroad laborers, he was hailed as “Buffalo Bill” for his abilities. Respected for his in-depth knowledge of the plains and prairies, he became one of the Army’s most valued scouts. They saw him as a man of character—dependable, reliable, and worthy of their trust.

When they needed someone who could, Cody did.

I can and I will.

But the West remained the limit of Cody’s horizon…that is, until he met a writer with the pen-name Ned Buntline—a man who would turn Cody’s life upside down.

“Buffalo Bill” went from being a nickname to becoming a “character” whose exploits were celebrated and displayed, on stage and in the pages of a growing number of popular stories. Some of his exploits had a grain of truth at their core. Others, however, were invented wholesale in an effort to fashion a new icon of the American frontier—an amalgam of the likes of Daniel Boone, Davy Crockett, Natty Bumpo, Paul Bunyan, and even Johnny Appleseed.

The result was that within a few years, “Buffalo Bill” became a household name, both in this country and abroad. And, as Buffalo Bill’s fame spread, William F. Cody was vaulted from near-obscurity to become, under that persona, the first true “celebrity” of modern times.

“I’m no scout now,” Cody declared in 1873. “I’m a first-class star!” The meteoric rise of Buffalo Bill fueled Cody’s ambitions as nothing else had. By the early 1880s, wealthier than he had ever imagined, Cody felt “stimulated to greater exertion” and desirous of “increas[ing] my ambition for public favor.”

I can and I will.

Cody looked for new horizons to conquer—and conquer he did. Premiering in 1883, Cody’s innovative traveling entertainment spectacle, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, succeeded brilliantly. For three decades, as its marquee star, impresario, and director, Cody toured with his show throughout North America and Europe, appearing before millions of people from all walks of life.

And, as he did, he was no longer a “Man of the West”: William F. Cody was now a “Man of the World.”

I can and I will.

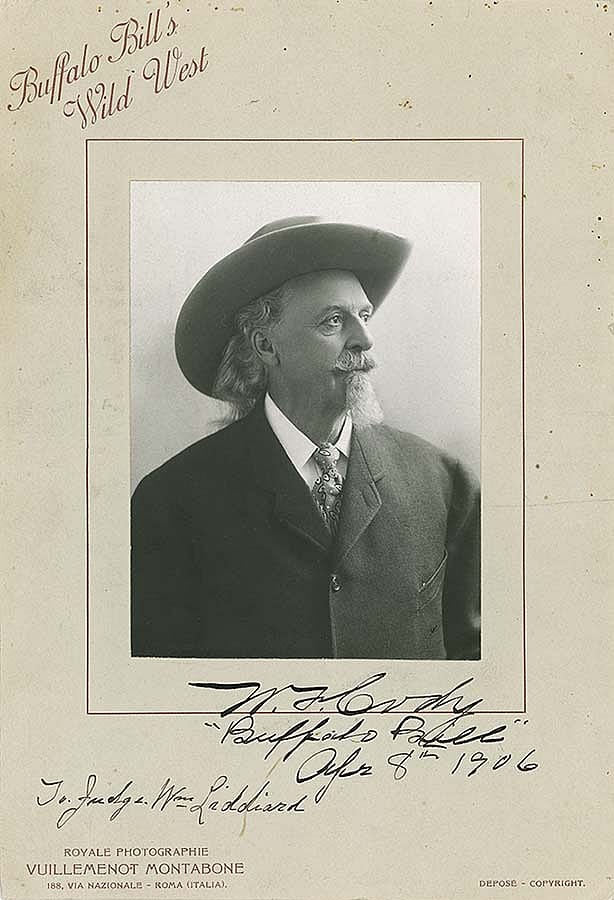

As “Buffalo Bill,” William F. Cody would forever change how people viewed the American West. Yet the more the character of “Buffalo Bill” succeeded, the more Cody worried that his own character—his very identity—was fast receding.

The Old West was vanishing, and along with it, so much of what had been meaningful to him—scouting, most of all. “Scouting in the West is a thing of the past,” he noted wistfully in 1901. “It’s a lost occupation.” His “pards”—the scouts and trackers with whom he’d been associated—were dying off, one by one.

The Old Scout knew the time was fast approaching when “Buffalo Bill” himself would become irrelevant. Even then the persona seemed less a “character” than a caricature. Take away the props, the costume, and the performances, and nothing tangible or lasting would remain of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. And once that happened, what would Cody have to show for it? What would he have to show for his life?

I can and I will.

Increasingly, too, the demands of touring, performing, being in the public arena day in and day out—day after day, year after year—were taking their toll. His personal life was a shambles. So, too, were his finances: Time and again, he’d spread his wealth around, giving away vast sums to family members and friends, and losing millions in dubious investment schemes.

Seeking to find a renewed sense of meaning and purpose in his life, the Man of the World felt the West beckoning him—the West of his youth, the West he had come to know and love. Growing up there in his formative years, Cody viewed the West as “the young man’s opportunity.”

He was no longer a young man. Yet now, in the twilight of his life, the West still held out its promises to him, “today more than ever.”

I can and I will.

To the end of his days, William F. Cody would retain that eternal sense of optimism, an optimism grounded firmly in the expansive and boundless horizons of the American West.

Cody returned to the West. To hunt. To rest. To refresh his spirits. But more than anything else, Cody went there to make a difference—to leave behind something tangible, a lasting monument that would serve generations to come. “My whole aim in life,” he asserted in 1902, “is to open this new country and settle it with happy and prosperous people, and thus leave behind a landmark of something attempted, something done.”

It all boiled down to that: Something attempted, something done.

I can and I will.

And, in the end, Cody did.

In a vast and arid region of northwest Wyoming, he sought and worked to realize a vision—to bring about “the sunrise of the New West, with its waving grass-fields, fenced flocks, and splendid cities, drawing upon the mountains for the water to make it fertile, and upon the whole world for men to make it rich.”

William F. Cody became, once again, a “Man of the West”—not of the “Old West” of his youth, but of the “Modern West,” still developing in our time. Yet it was not “Buffalo Bill” the character who did this, but William F. Cody, a man of character.

I can and I will.

A Man of Will.

About the author

John C. Rumm, PhD, was formerly Curator of the Buffalo Bill Museum, Director of the Curatorial Division, and Curator of Public History.

Post 287

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.