Adversity and Renewal | Plains Indian Culture

Diverse Cultures of the Northern Plains Indian Peoples: Adversity and Renewal

Themes of adversity and renewal have been of great importance to Plains Indian peoples in the past and the present, and will continue to be into the future. In this post, uncover more about the importance of material and spiritual cultures of Plains peoples since being placed on reservations in the late 1800s as you explore concepts of identity, community, land, spirituality.

Scroll to explore all four sections of Adversity and Renewal… Or choose one in the list below to skip directly to it…

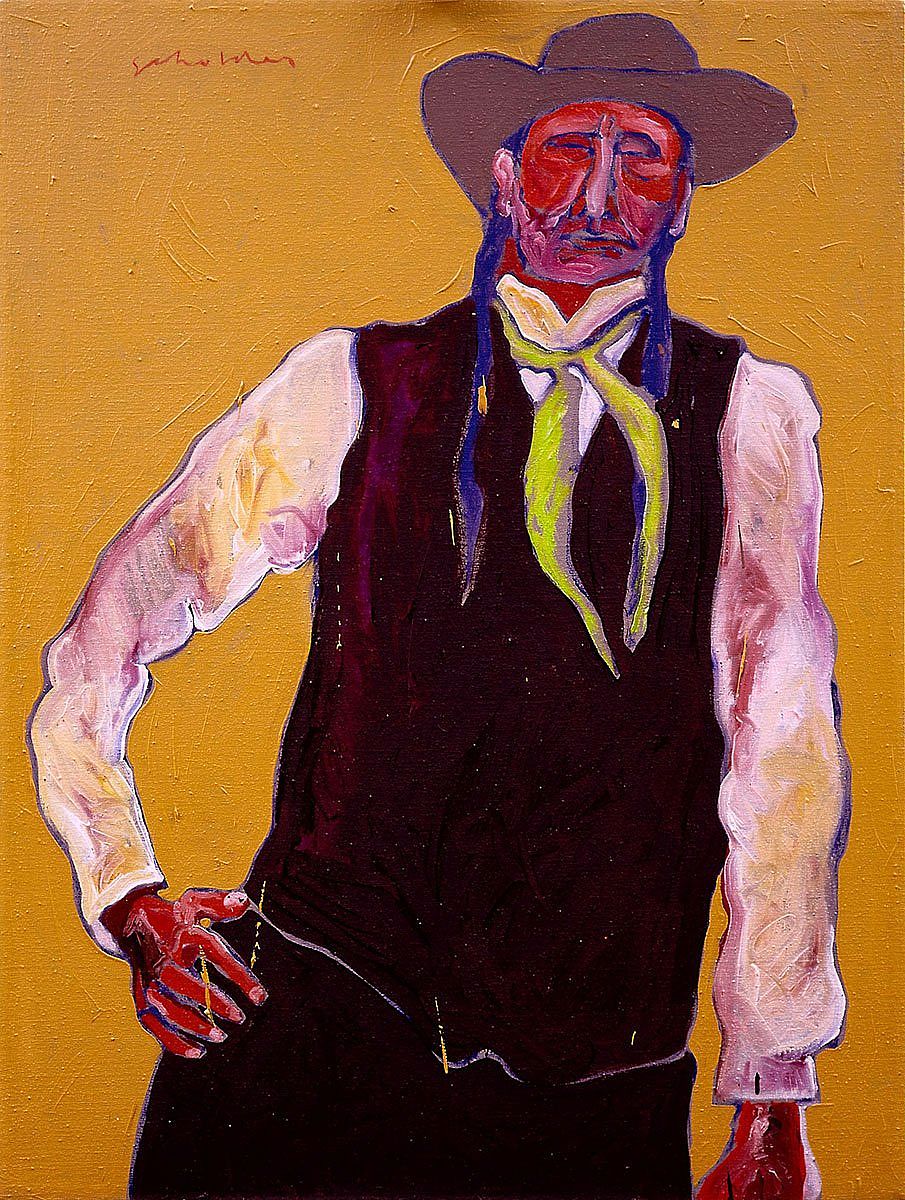

Identity

Something basic to every human being is that you have to know who you are and understand that and be proud of that and, you know, feel a sense of worth. —Calvin Grinnell, Numakiki/Nuxbaaga (Mandan/Hidatsa), 1999

Identity: Tribal Identity

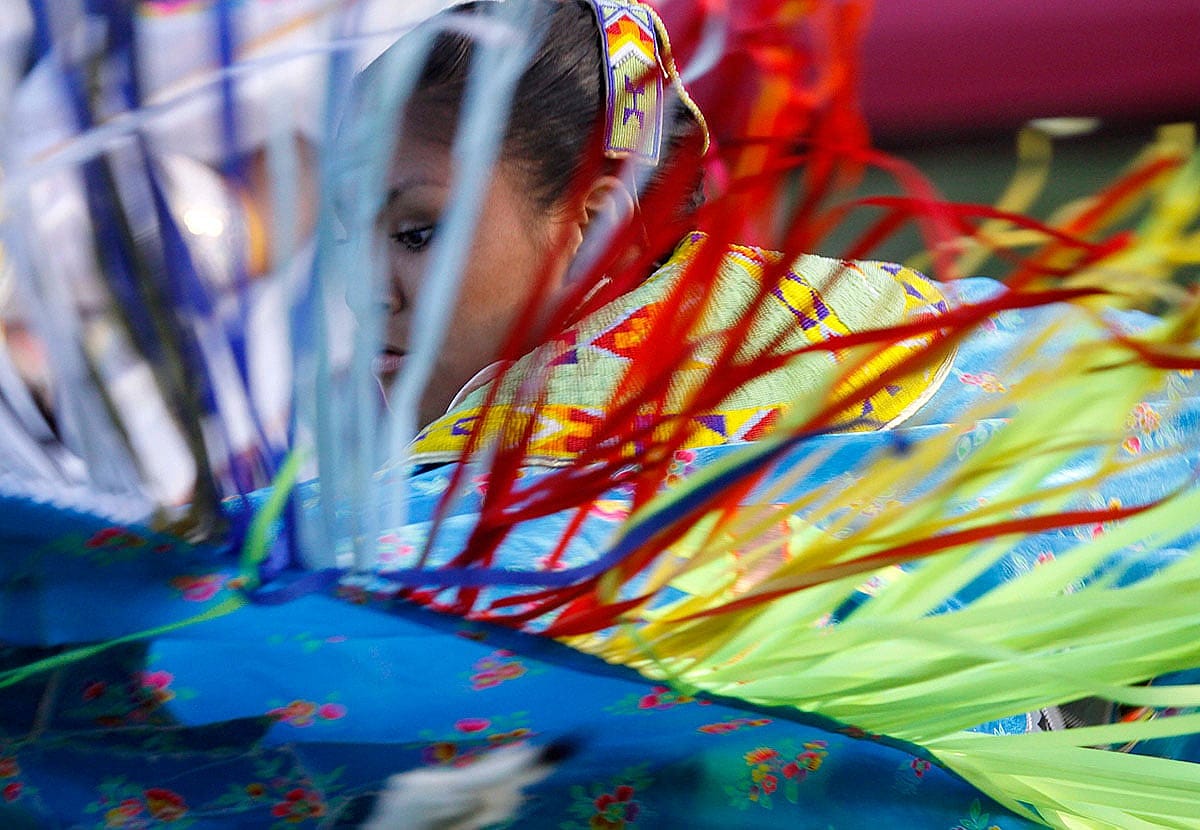

We preserve our culture, I believe, through round dances. They call them powwows now—they used to be called celebrations, they were celebrations of life. …The first powwow was, all the people got together and they started calling people, saying, “Oh, okay, let’s get together, see who is all alive still.” And pretty soon it became an annual thing. Each year they would get together so that they could see who had passed on, and how they were doing, and that was the first powwows. So they were celebrations of life; that’s how they were originally started.—Lyle Gwin, Nuxbaaga (Hidatsa), 1999

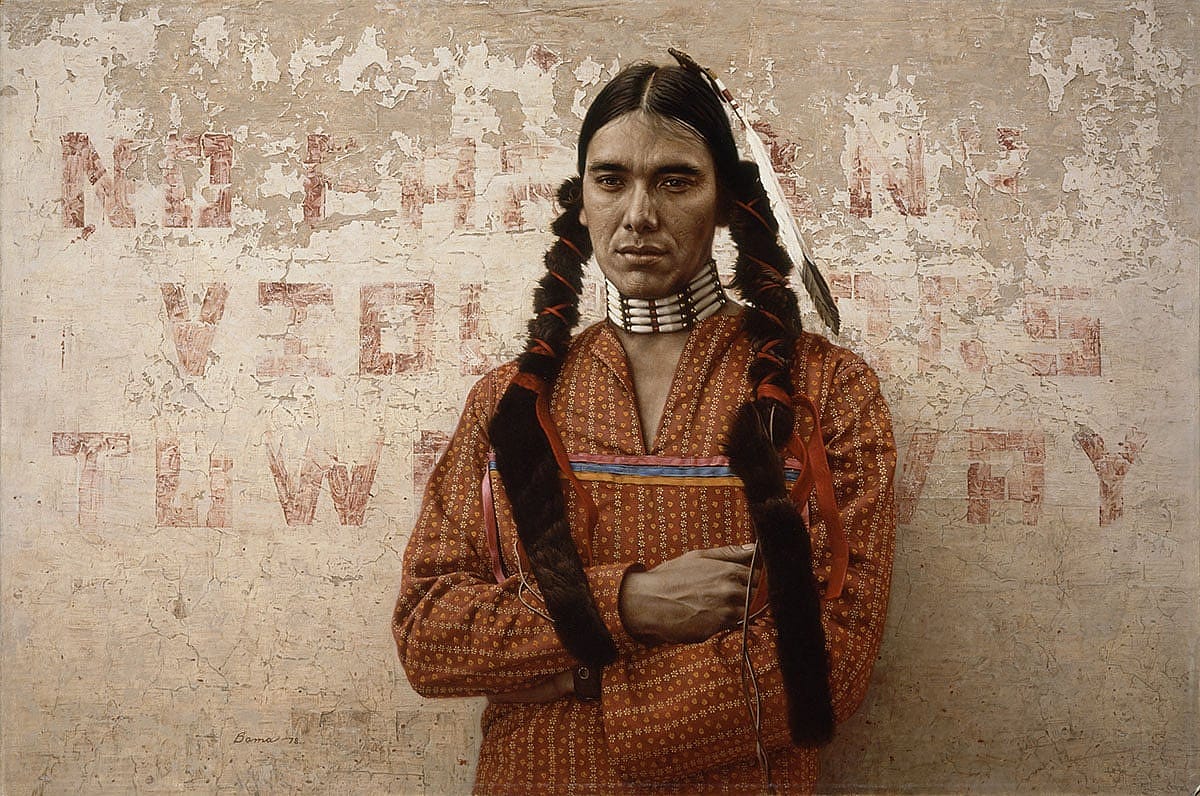

I moved to Wyoming during my fourth grade year and lived on the Wind River Indian Reservation. I was clueless about my culture. I dwelt on negative things, such as the “drunken Indian” that many of us see passed out in the city park or staggering along the sidewalk. I began to feel ashamed of who I am because I knew that part of me is common to that Indian we all see. I didn’t think it was right to take part in such things as sweat lodges and other ceremonies, for I was brought up in a strict Catholic family. For many years I held all these thoughts and feelings within me. Being Native American doesn’t mean I’m destined to be an alcoholic, or anything that is commonly associated with Native Americans that some people might look down upon. It would seem easy to come to a conclusion such as this but was truthfully hard for me to reach. I now have pride in who I am. I am slowly learning about my culture. I appreciate that I have a culture to learn about and be a part of.—Matthew Watt, Hinono’ei (Arapaho), 1999

Identity: Language

Recent years have seen a growing interest in preserving Native languages. Many are in danger of being lost, with only a handful of fluent speakers, and fewer young people learning them. In an effort to help teach young children, the Hinono’ei (Arapaho) Nation collaborated with the Walt Disney Company to produce Bambi, the classic animated movie, in the Arapaho language.

I went to a school where they were all Caucasian, and I was the only Indian there. And I know how it felt, you know. And today I think it’s kind of turning around, the non-Indian is trying to learn our Native American traditional way and culture. And they want to understand. Which is good. And my grandchildren here, I talk to them in our own Native language. I didn’t do that to my kids because I wanted them to learn the English language, Now, today, I think that was a mistake that we made. —Hazel Blake, Nuxbaaga (Hidatsa), 1999

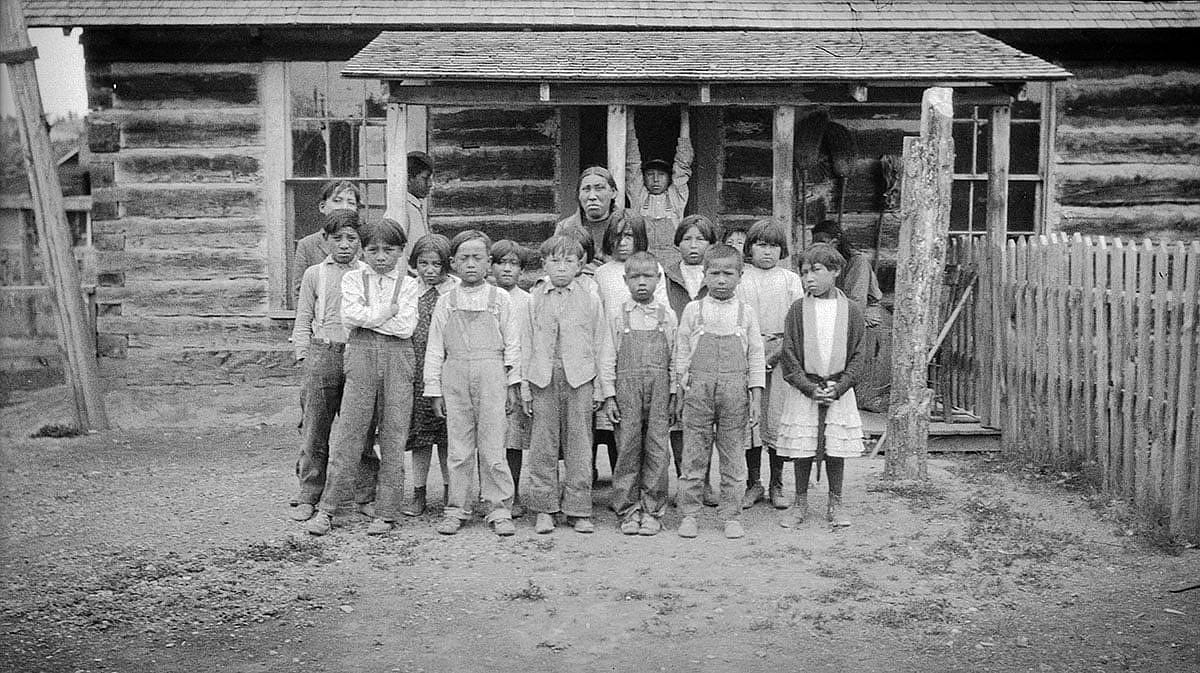

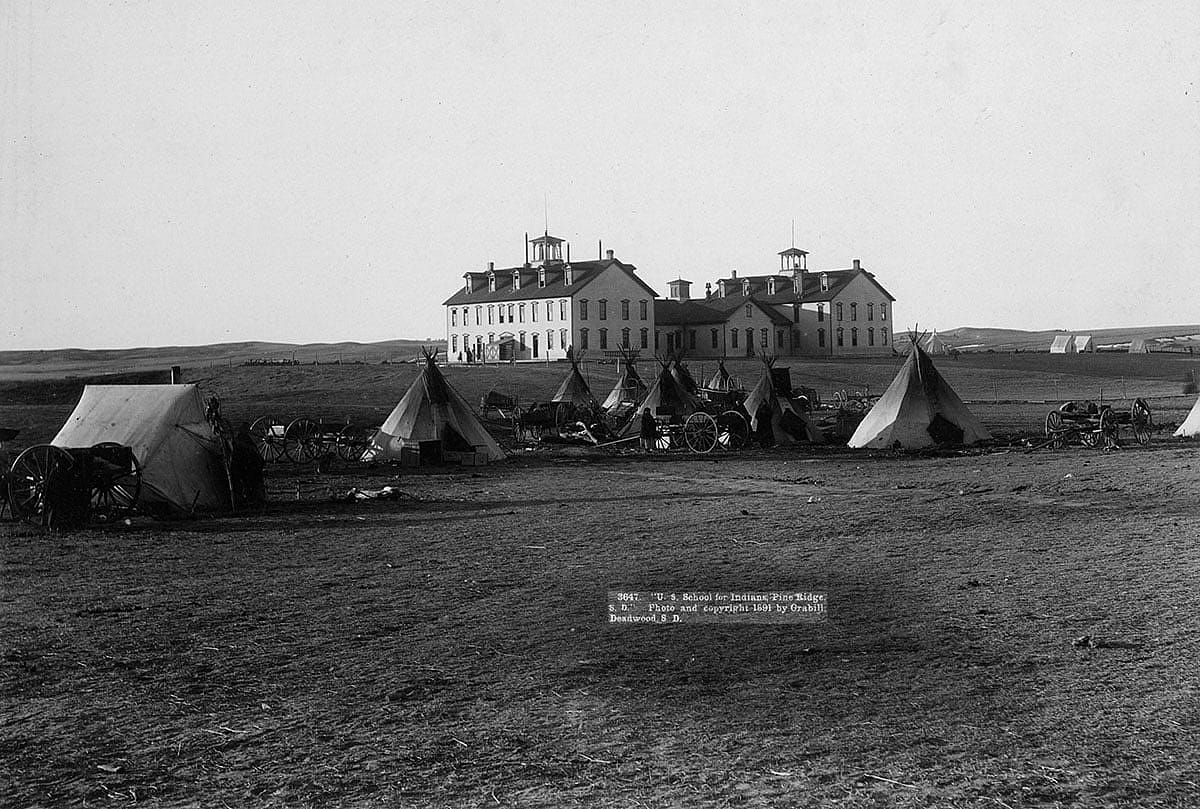

Identity: Boarding Schools

And I remember him telling me that the first word in English that he knew was the word “broom.” And I said why was that the first word you knew? He said, “Well if you got caught talking ‘Indian’—in their case Arapaho—they made you kneel on that broom for three or four hours until you wouldn’t talk your language no more.” —Patrick Goggles, Hinono’ei (Arapaho), 1998

My grandma, her and her sisters, they would go down in the basement at night after all the matrons went to sleep. And then they swore, they made a pact with themselves that they would not let the language die, they would not forget it. And they would sit there and they’d talk Hidatsa to each other, back and forth. And if they knew other languages they’d practice those too. When she come back from boarding school, with all her grandchildren and her children she would not speak English. If you spoke English to her…she wouldn’t talk to you no more, because of all the beatings she got for speaking [Hidatsa]. She could read it, write it; she knew it, but she spoke Hidatsa and we had to speak Hidatsa to her whenever we addressed her. —Lyle Gwin, Nuxbaaga (Hidatsa), 1999

Identity: Contemporary Education

Since the 1970s, many tribes have established their own schools. And in the Northern Plains there are 17 tribally controlled community colleges. The tribally controlled schools and colleges phenomenon is an extremely important step in Native communities.

Little Big Horn College, where I have served as president for 16 years, is an example where the Crow scholarship from thousands of years of our national life has come into the curriculum. Tribal schools have the standard curriculum as well so that it’s a partnership curriculum.

You can’t just order up a shelf full of books and say, ‘Okay, all the knowledge we need is here.’ Our entire community is a library and a learning lab. —Janine Pease Pretty on Top, Apsáalooke (Crow), 1998

Community

As a community, we need to take a stronger stand and say, ‘Yes, this is who we are. This is where we need to go. We’re Indians; we can not only help each other but help others.’ If we take the right steps as a community we could do a lot of things. The world in general could learn a lot from us. We’ve held those traditions and customs hundreds and hundreds of years. We need to take advantage of the stuff that we know and apply it to our younger generation. —Ivan Posey, So-soreh (Eastern Shoshone), 1998

Community: Sovereignty

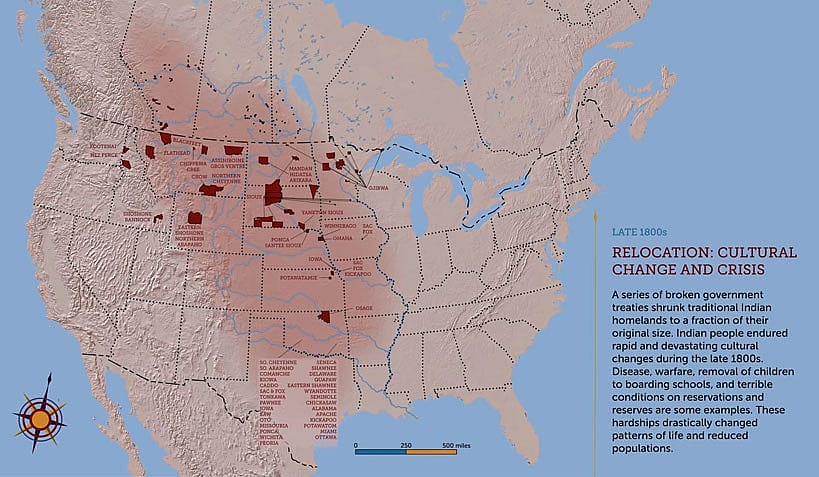

Indian peoples’ independent, sovereign status was recognized by the earliest European explorers and settlers, and eventually by the United States government itself, in treaties signed with Indian nations. Despite that centuries-old legal precedent, Indian people have had to struggle for self-determination.

I look back a hundred years ago, probably around the 1890s, where as a people I don’t think we was expected to make it. We was banned from using our tradition, our culture around the 1900s. People probably thought we wasn’t going to be here. Through the ’20s and ’30s, we start forming our own governments. We survived the Termination era. We still make our own laws for our own tribes. We gotta look back and realize what struggles our ancestors did for us. And we still have those cultures and those traditions. We’re still Indians. And we’re still here, so that really shows our resilience. —Ivan Posey, So-soreh (Eastern Shoshone), 1998

Community: Reservation Life

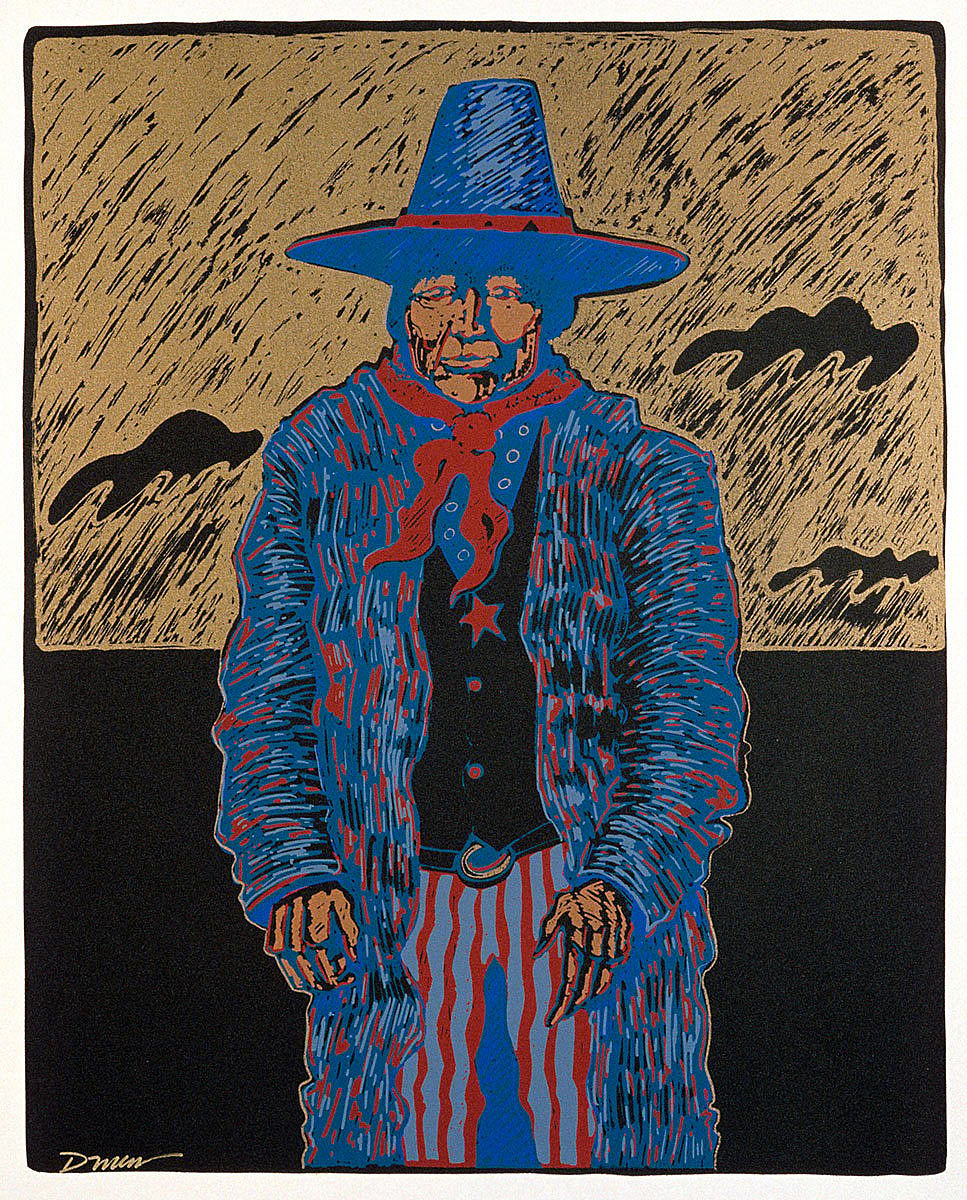

Architect Dennis Sun Rhodes, Hinono’ei (Arapaho), designs buildings to serve the needs of contemporary Native communities and resonate with their traditions. His Division of Indian Work building in Minneapolis incorporates symbolic elements reflecting different Twin cities Indian cultures—a moon, a drum-shaped skylight, animals, and a ceremonial hearth.

Although many Native people leave their reservations for education and to work, they also come home—to teach, to heal, and to carry on traditions. There is a desire and, indeed, a need to deal with social and economic problems that persist in many communities.

Community: Economic Issues

In 1948, the Three Affiliated Tribes (Arikara, Hidatsa, and Mandan) regretfully moved out of their homelands on the Missouri River to make way for the construction of the Garrison Dam. They are still struggling for compensations.

We were promised a lot of new infrastructure to…rebuild our communities, including a new hospital, which was never built; community buildings, only now being completed, partially with tribal funds; and a rural water system, using some of the water from the lake for which we had sacrificed our way of life…. We…have been waiting for more than fifty years…. —Russel D. Mason, Sr., Chairman, Tree Affiliated Tribes, 1998

Community: Tribal Government

Traditionally, Indian tribes throughout this part of the country and probably all parts of the country resolved these kinds of conflicts they had—either among themselves or between individuals—through the various military and social and religious societies that existed within the tribe. When the reservations were set aside as a permanent homeland of the tribes, the federal government, as part of the policy of assimilation, prohibited these societies from operating, and this created a vacuum. —John St. Clair, 1998

In the reservation era, Native people have adapted traditional forms of leadership and tribal organization. Elected tribal councils and, more recently, tribal courts have been at the forefront of the struggle for self-determination and recognition of tribes as sovereign nations.

I thought long and hard about it for a number of years before I actually got on a council, but it was a willingness to serve. It was willingness to try to make a difference, to contribute ….I look at it as being a public service; you’re there for other people. You make sacrifices like we all do in all of our jobs. I realize we got a long ways to go, you know, it’s a big responsibility. We’ve got the kids, we’ve got the older people and everybody in between. … We got issues, water issues, taxation issues. It’s almost overwhelming sometimes. But I think what drives me is the people aspect, the social aspect. —John Posey, So-soreh (Eastern Shoshone), 1998

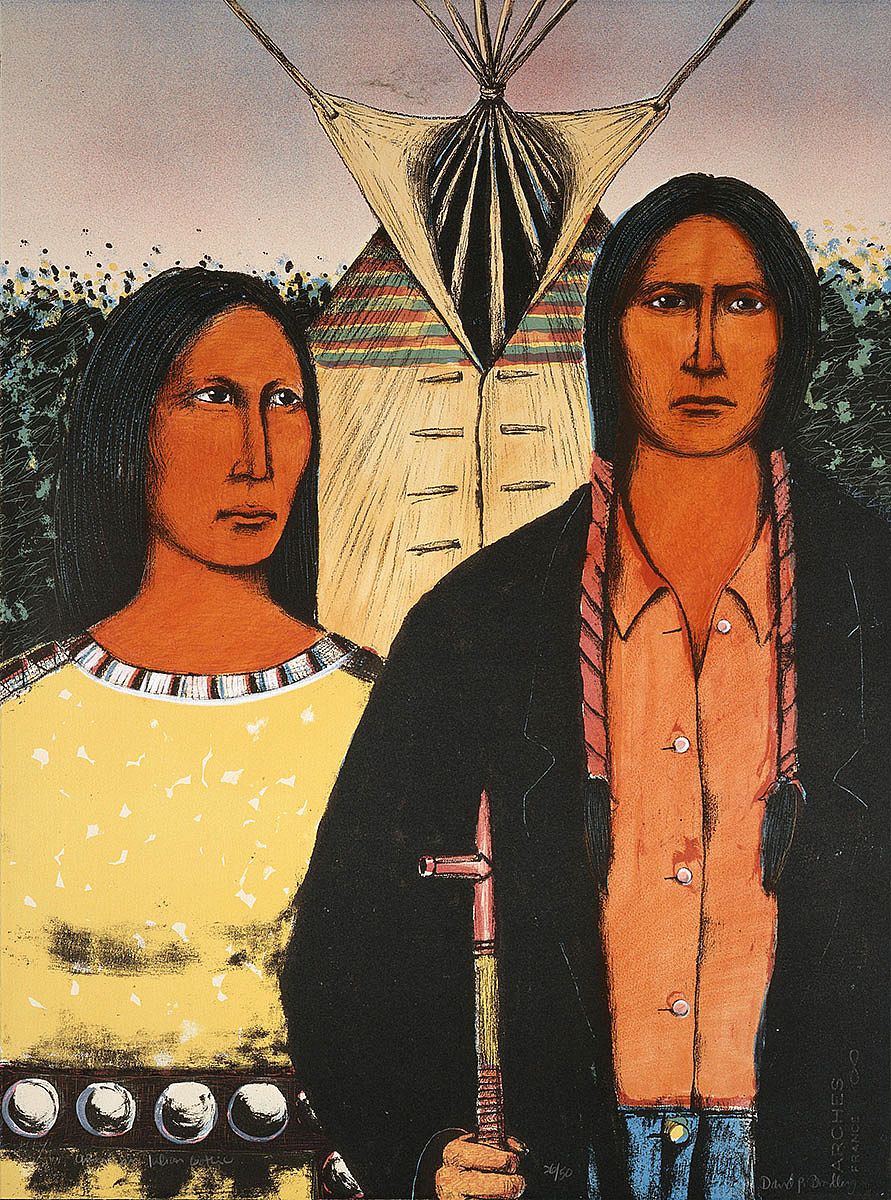

Land

My land is where I set my tipi. When I set my tipi I start with one pole. One pole rests at the western foothills of the Black Hills. One pole rests at the shores of the big lake in the mountains—Yellowstone Lake. One pole rests at the great falls of the big river. And, the fourth pole rests at the junction of Yellowstone River and Missouri River. That is my country. —Apsáalooke (Crow) leader, 1868, as told by Joe Medicine Crow, Apsáalooke (Crow)

Land: Reservations

In the nineteenth century, many tribes were forced onto reservations in the American Midwest, often far away from their own lands. Displacement was devastating to people whose spirituality and identity, as well as livelihoods, were inseparable from the land they had lived on for generations.

At the same time Native people were being confined to reservations, they were discouraged or forbidden to practice many traditional ceremonies and celebrations integral to their community life. Rather than letting these traditions die, they adapted them.

Land: Urbanization and Relocation

We didn’t have no money so we had to find a job. Where can you find a job in Van Hook? There was no jobs there so a lot of people went away to Chicago or California. They called it the Relocation. They sent them out, the families. They had a heck of a time when they went in the big city. They just didn’t make it. They all came back. —Hazel Blake, Nuxbaaga (Hidatsa), 1999

From the 1930s to the 1960s, thousands of Plains Indian people were relocated from reservations to big cities. The federal government promised a better life. But having left their families, friends, and traditional way of life, many suffered poverty and loneliness.

To fill the gap left by overwhelmed and under-equipped Relocation offices, local organizations and “friendship centers” evolved to bring Indian people from different tribes together. New support networks were formed.

Not all Indian people who come to cities want to simply blend into the “mainstream.” Many have struggled for visibility in the urban landscape, and to define their identities as modern urban Indians.

Land: Water Rights

Western water law discourages conservation and efficient use of water; use it or lose it, right? So you’ve got these non-Indians out there taking as much as they can, and they’re destroying land, they’re destroying water quality, they’re altering the hydrologic cycle of our areas, and they’re mismanaging water, they’re wasting water every day. And according to the constitution of Wyoming, which came in after the 1868 treaty, they claim all the water in the state. Well, how can you come in after somebody else is already in place—by treaty of 1868—and then come in 1890 and say you claim all the water, you own all the water? —Wes Martel, So-soreh (Shoshone), tribal water consultant, 2000

In the arid West, state governments allocate rights to the water in rivers. Much of it goes to irrigation. Sometimes little is left for anything else.

My mother would cut us a willow pole and we’d put a short fishing line on the end of it and a hook and worms. And we would dangle that in the river and catch mostly flathead chub. But at that time there were lots and lots of them, and that fish has essentially disappeared from the Wind River in this area. What we’re trying to do with ‘instream flows’ and maintain a decent flow in the Wind River benefits all people. It benefits the irrigators. It benefits the tribes. It benefits the fishermen…. It benefits people that just want to take pictures. It benefits all the people that live along the river. Well, wouldn’t it be a hell of a lot better if there was water in the river, rather than a dry stream bed? —Richard Baldes, So-soreh (Shoshone), 2000

The Arapaho and Shoshone people have fought legal battles to establish instream flow claims, keeping enough water flowing in the Wind River to maintain the ecosystem.

Land: Sacred Lands

Throughout these past decades this Medicine Wheel, Medicine Mountain, has been frequented by tourists, and other people that did not really understand what this place was all about. —Steve Brady, Tsistsistas (Cheyenne), Medicine Wheel Coalition for Sacred Sites, 1996

In May 1996, President Bill Clinton issued an executive order that federal land managers are to: (1) Accommodate access to and ceremonial use of Indian sacred sites by Indian religious practitioners; and (2) Avoid adversely affecting the physical integrity of such sacred sites.

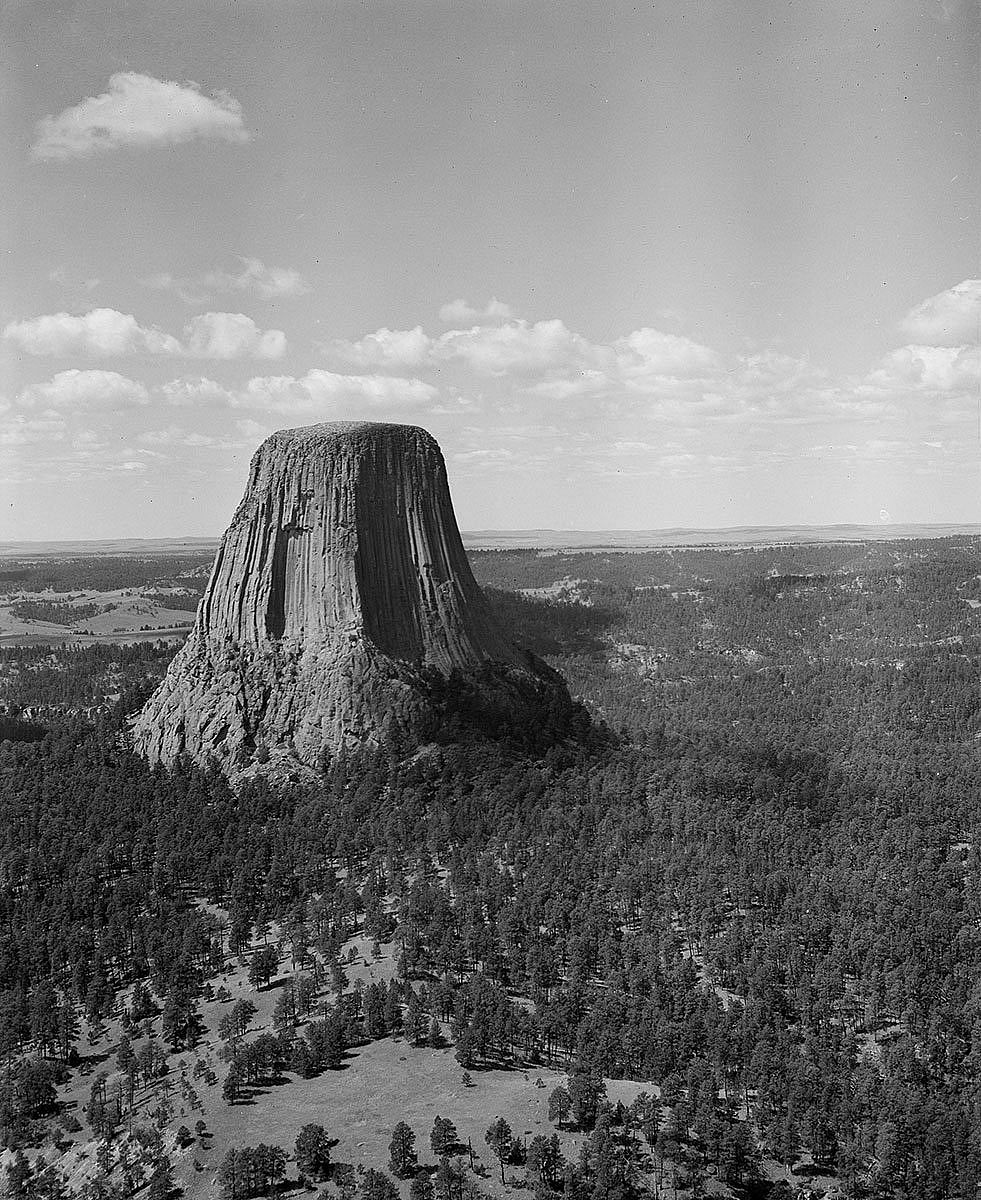

The ceremonial use of sacred sites like Devil’s Tower has sometimes come in conflict with development, mining, mainstream environmentalism, and recreational uses.

There’s going to have to be a considerable amount of educational effort by Native Americans to continue to have their sacred sites protected. And there has to be a common understanding that these are indeed places of worship. —Steve Brady, Tsistsistas (Cheyenne), Medicine Wheel Coalition for Sacred Sites, 1996

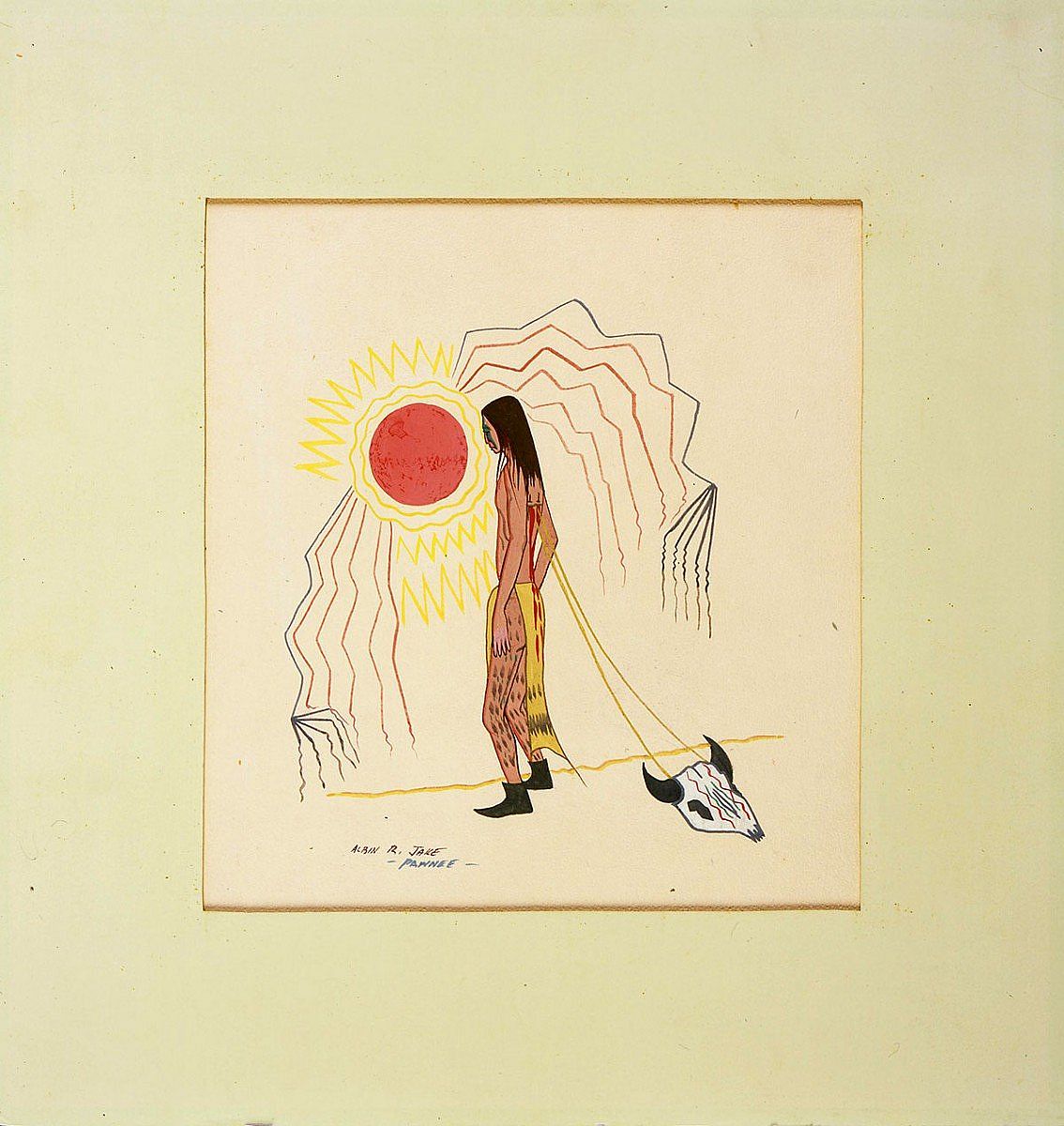

Spirituality

We respect everything that the Creator has given to us. We respect it because everything out there is living—the sun, the moon, the stars, the clouds, the sky, the mountains, the trees, the rocks, the grass, the water—all those things are living, and they’re all related. We’re part of that relationship. The Creator gave us these things for our survival. So, therefore, we respect these things, what he’s given to us. We honor these things. So that’s what we call our way of life, what they call a religion. —Curly Bear Wagner, Amskapi Piikani (Blackfeet), 1999

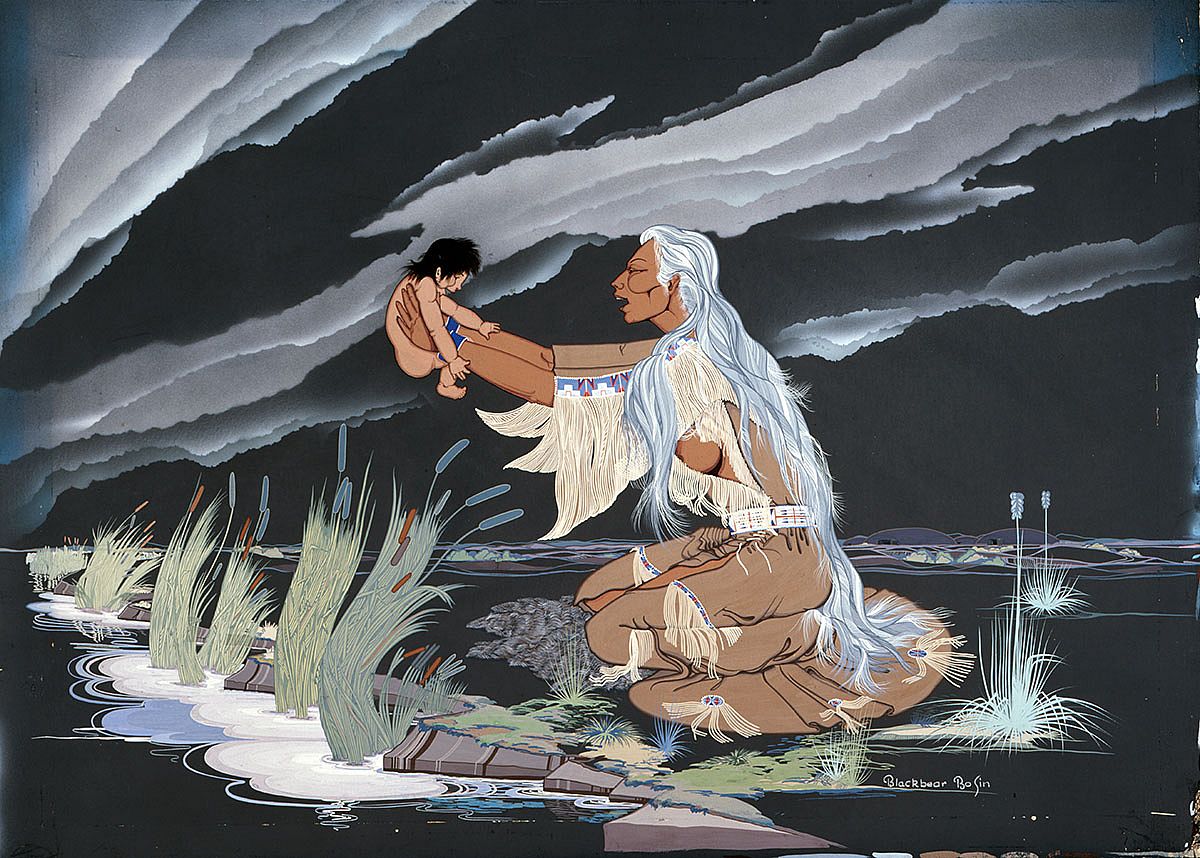

Spirituality: Passing on Traditions

If a young child didn’t listen they could actually bring danger to the whole camp, and so at a very young age, young children were taught to listen. And a part of their education was through storytelling, and through storytelling they learned about respect toward their environment, respect toward the earth, the trees, the land, the water. Not only that, they learned about respecting wildlife, the animals. They shared the world with the animals, and so it was important to know, to understand how they fit into the whole picture. —Merle Haas, Hinono’ei (Arapaho), educator and storyteller

Contrary to popular belief, education, the transmission and acquisition of knowledge and skills, did not come to the North American continent on the Nina, Pinta, and Santa Maria. Education is as native to this continent as its Native people. —Henrietta Whitman, Tsistsistas (Cheyenne), 2000

I think the first step is to start teaching the way my grandma taught us. The faith and then the language, those things have to be re-instituted. It made a great comeback here in the mid-80s and early 90s, our ceremonies, and then now the young people are starting to practice them again. Which is a good thing, when they bring back the sacredness of our beliefs, then they’ll start to move forward. —Lyle Gwin, Nuxbaaga (Hidatsa), 1999

Spirituality: Search for Hope

Turned away from their homelands, faced with the destruction of their way of life, and forbidden to observe their sacred and ceremonial traditions, many Native people looked to new sources of faith and hope.

People like my parents thought, “Now here are some people that are going to help us learn their ways. We are stepping into a world that is not our own, but we have to adhere to it. These people are showing us the way, but the main thing is that they want to save our souls, through that Pierced One, the son of the Creator. —Alma Snell, Apsáalooke (Crow), 2000

Increasing religious freedom has encouraged a resurgence of spiritual and ritual traditions. The Native American Church, which first emerged in the late 1870s, combines elements of Christianity with traditional practices.

Spirituality: Reclaiming Sacred Objects

In the reservation era, many sacred artifacts, and even human remains, found their way out of Native communities and into private and museum collections, where their spiritual significance was not properly respected. Reclaiming them has been an uphill battle.

Those things are sacred to our people…. This bundle may be handed down through generation to generation, songs may go with it, a certain way of smudging may go with it; there’s certain functions that relate to that bundle. These are our national treasures today that protected our people and helped us survive the great difficulties that we had to go through—starvation, winter, being attacked by enemies, coming of the white man. These things were our helpers, and so…you talk to any traditional Indian, he won’t talk too much about those things. We make it clear that they are sacred and certain things we can talk about or we can’t talk about, those bundles. —Curly Bear Wagner, Amskapi Piikani (Blackfeet), 1999

In 1990, President George Bush signed the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) into law, protecting human remains and funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony. It was an important, if partial, victory for the Indian community. “Whoever knowingly sells, purchases, uses for profit, or transports for sale or profit, the human remains of a Native American without the rights of possession to those remains…shall be fined…or imprisoned not more than 12 months, or both, and in the case of a second or subsequent violation, be fined in accordance with this title, or imprisoned more than 5 years, or both.—[H.R. 5237] Sec. 4. Illegal Trafficking

Spirituality: Recovery

We still face that issue of drugs and alcohol, and violence…. I think we have the tools here to better deal with it. I think if you go back to some of the cultural aspects of who we are as Indians, I think personally drugs and alcohol has a lot to do with the breakdown of the family. I really work really close, and I have a really good relationship with my son; I think he’s at a real crucial point now, he’s a seventh grader. I ask him what’s going on about every day. I realize the pressures that are on him now; it’s just being able to spend time with him, and talk to him, and have that relationship. —Ivan Posey, So-soreh (Eastern Shoshone), 1998

I’ll do anything that I need to in order to keep my sobriety and I’m open to a lot of different ways. My sobriety means a lot to me and I’d like to see more of the people that I grew up with in a program like this. There were so many of us when I was growing up and we’d all go to dances around here and it was great. And we all took a little pact and said we’re not going to end up like our parents and there’s probably just one or two of us that didn’t have a problem with alcoholism.

I’d forgotten my culture, I’d forgotten the language, I’d forgotten the customs and practices. When I came to the Ini’pi [sweat lodge] and I tried to put into perspective how I felt while I was inside, something spiritual happened to me inside. There wasn’t any bolts of lightning, but I felt some strength, I felt some real power, something I’d never felt before. And for that whole week, I spent that week thinking about what had happened to me inside, I didn’t think that much about drinking. And it was the spirits replacing that alcohol, and I held that. I’ve never felt comfortable with sobriety; I’ve never felt comfortable with not drinking because I started drinking when I was 13 years old and it had stayed with me all my life. But from the strength of the Ini’pi, I’m not just comfortable with it anymore, I’m at home with it.

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.