Honor and Celebration | Plains Indian Culture

Diverse Cultures of the Northern Plains Indian Peoples: Honor and Celebration

Ceremonies have been important to Plains Indian life in the past and continue to be in the present. In this post, uncover more about the importance of celebration and ceremonies as you learn about activities and rituals unique to each stage of life, from childhood, through youth, into adulthood, and finally for elders.

Scroll to explore all four sections of Honor and Celebration… Or choose one in the list below to skip directly to it…

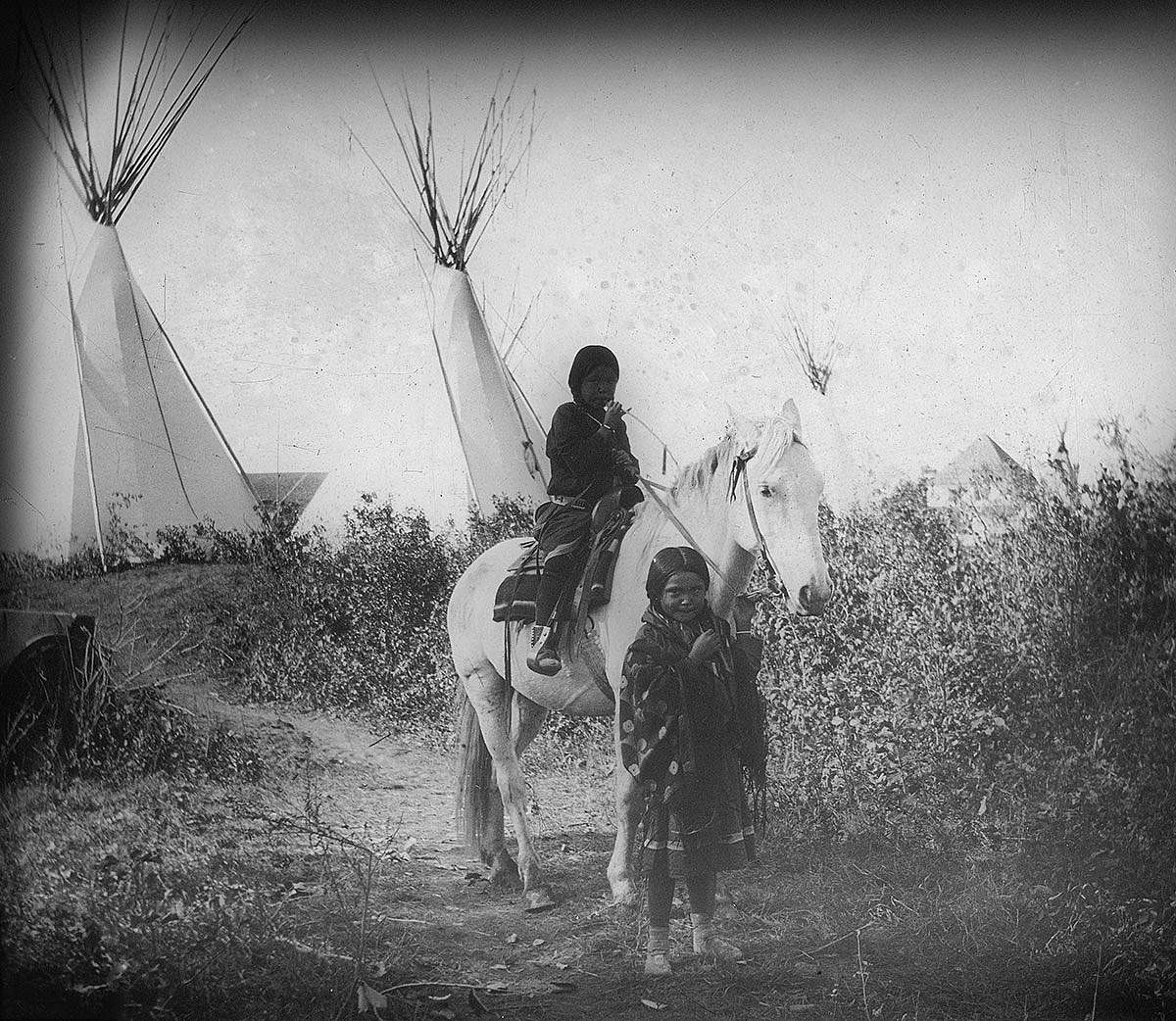

Child

Children learned their roles in life by watching, listening, and imitating adults. Girls played with miniature tipis and dolls. Boys made arrows and went on mock hunts. Many life lessons and tribal values were conveyed through storytelling.

Child: Hills of Life

A man lived in a tent that stood alone. Something came toward him from the East. It was a young buffalo bull. The man went to head it off but it went around him. The fourth time he succeeded. Then the bull said, “I have come to give you the buffalo. I give you myself. I have come to tell you of the life you will have.” —Traditional Hinono’ei (Arapaho) story, 1903

For the Hinono’ei (Arapaho), and several other Plains groups, life was organized around ceremonial lodges, or societies, each with practical and ceremonial traditions. As they aged, men and women gained knowledge, skills, and honor through their membership in these lodges.

For the Hinono’ei (Arapaho), the four “hills of life”—childhood, youth, mature adulthood, and old age—correspond to the four sacred directions and four seasons. Each stage of life is a preparation for the next.

Child: Naming

The elder walks a few steps to the east, pausing to pray for the beginning life of the child. Then he moves a few steps to the south and he prays for the teen years of the child’s life. Turning toward the west, and then facing north, he prays for a blessing on the child’s old age…. —Joan Willow, Hinono’ei (Arapaho), 1984

Names traditionally give their owners something to live up to. They usually come from brave deeds or extraordinary events, or from good omens in vision quests. Successful leaders’ or elders’ names are often taken as tributes.

Today, English and Indian names are given to children at birth. Giving an Indian name forges links with family members who have passed on, and with the larger tribal community, both contemporary and historic.

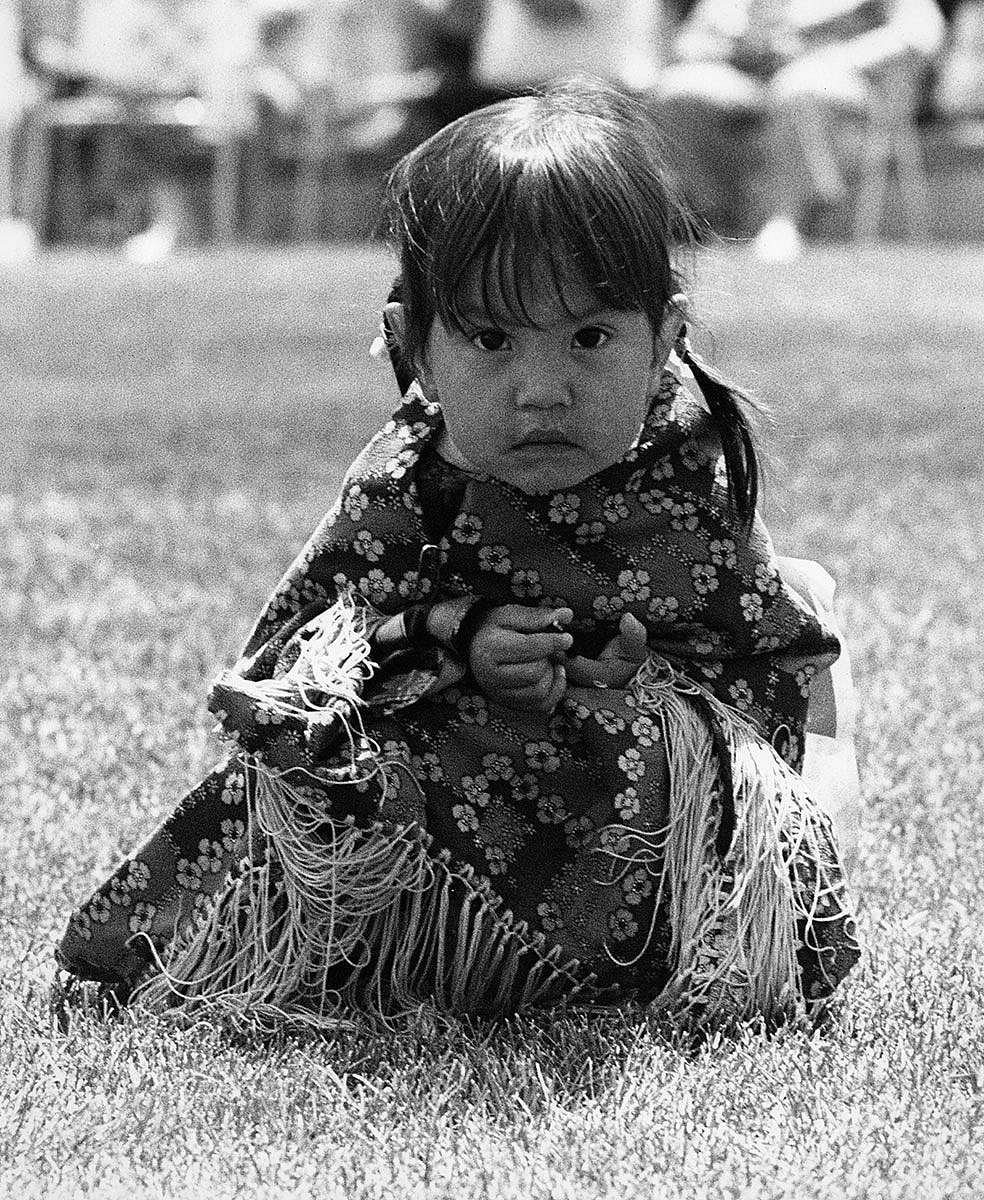

Child: First Powwow

Children participate in powwows from the time they are babies. Recently, a “tiny tots” category has been added to the dance competitions, so agile toddlers can participate along with their brothers and sisters. Some kids are shy; others can’t wait to begin.

Child: Continuity

…Sometimes we don’t know who we are…. I’d like to come back and teach the kids…. As soon as I learn to bring back my culture, come back and teach the culture back to the kids again. —Maria Lawson, Hinono’ei (Northern Arapaho), 1995

New and old skills develop side by side. In many communities, kids who play on championship basketball teams also play traditional stick and football games.

Youth

When they were about 12, boys began formal training to become hunters and warriors. Girls continued to develop skills they would need in maintaining their own households. Vision quests and special ceremonies often marked the entrance into adulthood.

Youth: Boys’ and Girls’ Lodges

Boys belonged to the Fox and then to the Stars. They joined them voluntarily…. There were no secrets attached to these two lodges. The other lodges—the men’s lodges—all had secrets. —Arnold Woolworth, (Southern Arapaho), ca. 1903

Young men went on their first vision quests, fasting and praying alone in a beautiful, often sacred, place, in search of guidance from a guardian spirit. An elder would serve as a confidant and interpreter for the spirit’s advice.

The Medicine Wheel in the Big Horn Mountains of Wyoming is an ancient stone structure. The site is held sacred by many Plains people.

At the same time, teen-aged girls joined the lower ranks of the Buffalo Woman Society. Several young women were chosen to be part of the annual Buffalo Woman Society dance.

Youth: First Hunt

I could sing a little boy song. It’s a song about sending this little boy hunting. And the song says ‘Have you seen our little boy? We sent him hunting.’ And kind of an answer, they said, ‘He’s at the crossroads—at the path where the roads cross each other. He’s sitting there cutting on the hindquarter of an animal….’ —Louella Johnson, Apsáalooke (Crow), 2000

Hunting was a man’s main economic duty, so boys began their training with bow and arrows and throwing sticks early. A first success—usually a bird, gopher, or rabbit—was celebrated with a giveaway and feast, often with the catch as the main dish.

Young Arapaho men weren’t allowed to join buffalo-hunting expeditions until their twenties. They were instructed in the ways of the hunt by several male elders, who also custom-made their arrows. The first kill was given to an elder who in turn offered prayers for good hunting and a good life.

Youth: First Hide

She’d have us girls in a circle in front of her and take that wet hide, and we’d all have the edge of it and we’d pull, one way or the other. We’d just pull and go in a circle with this skin until it stretched enough, it dried soft. —Alma Snell, Apsáalooke (Crow), 2000, talking about her grandmother, Pretty Shield

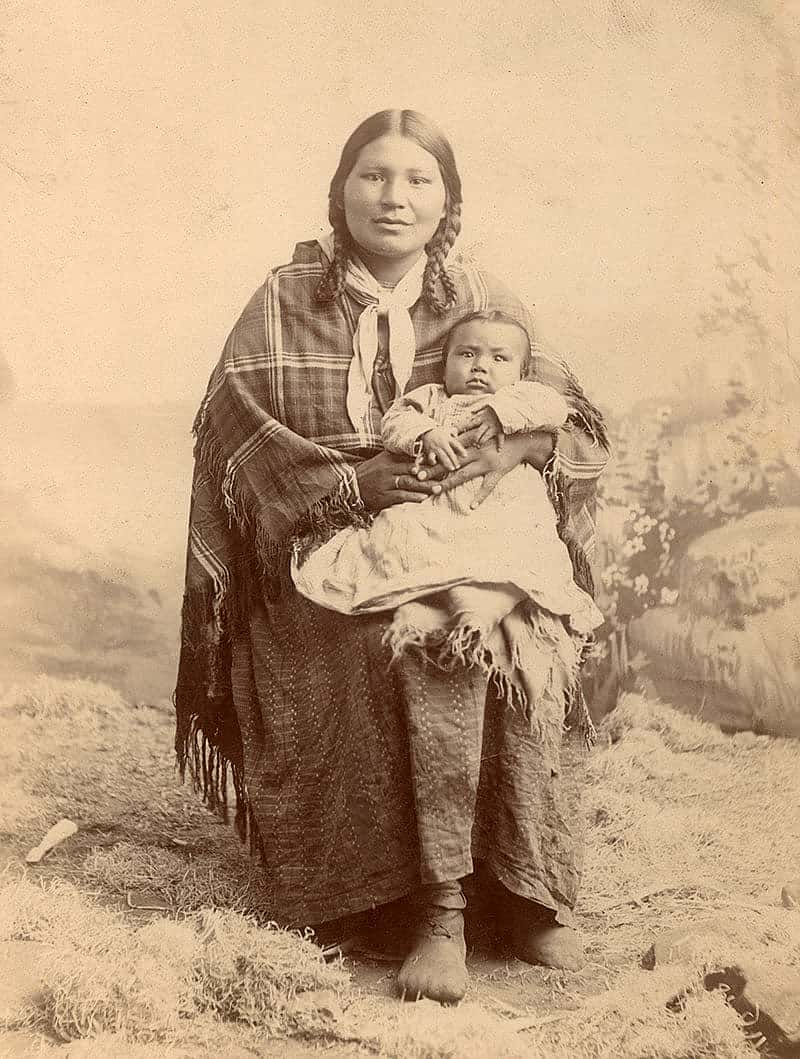

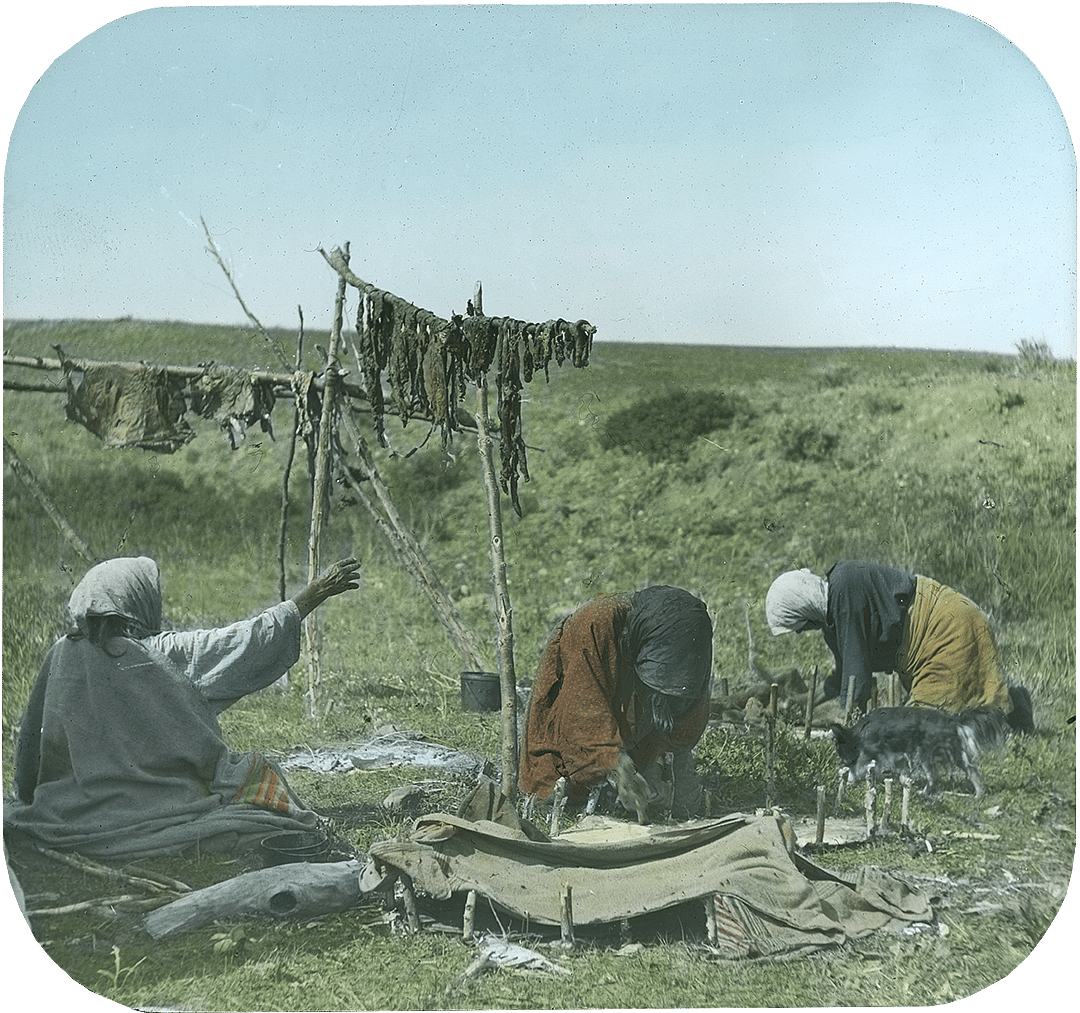

Throughout adolescence, girls continued to learn practical skills like cooking, sewing, decorating with porcupine quills, and the task of preparing hides, and sewing them together to make tipis. Her first hide was an important milestone in a girl’s passage into womanhood.

While they worked, mothers, grandmothers, and other female relatives passed on important skills and knowledge about women’s responsibilities. When they reached marriageable age, girls were often given their mother’s or grandmother’s awl case, scraper, or other useful tools.

Youth: Graduation

My culture is more than dancing and beading. It’s something I’ll take with me forever, in whatever I do…. And when I go away to college, I’ll take everything I learned with me… —Leann Brown, Hinono’ei (Arapaho), 1998

For graduations from Wyoming Indian High School, boys wear traditional ribbon shirts and girls wear beaded dresses.

…My family and my friends always support me. My culture helps me too. My mother taught me about the sacredness of sage. When I play basketball she always taught me to put it in my sock. She said it will protect me and help me whenever I thought I needed it. —Leann Brown, Hinono’ei (Arapaho), 1998

Adult

On the Plains, people depended on one another for survival. Everyone in the group had a responsibility. Men were trained to be hunters and warriors and women ran the households. Besides cooking, sewing, and taking care of the children, women pitched the tipis, butchered the meat from hunts, and prepared hides.

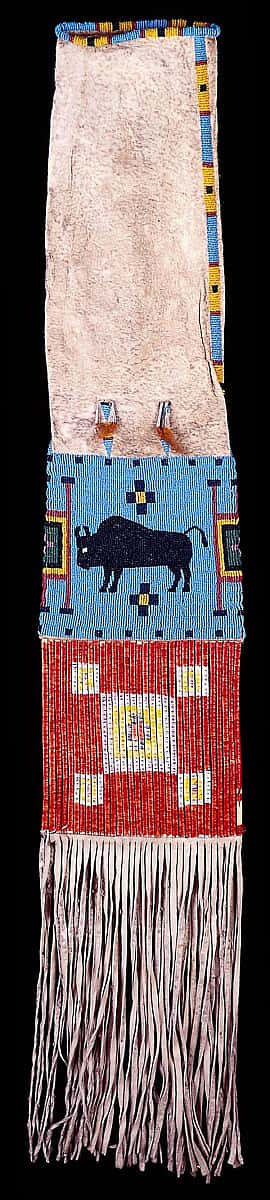

Adult: Buffalo Woman Society

Many Plains tribes had buffalo women’s societies. According to tradition, White Buffalo Woman brought the sacred buffalo calf pipe to the Lakota. She instructed women in cooking and other important skills of life and told them of their importance in Lakota society.

The Arapaho Buffalo Lodge included all the women in the tribe and was the equivalent to the men’s age-graded societies. Girls could join at age 15. As they grew older and gained skill and honor, they proceeded through degrees of rank, each with special regalia and songs.

Adult: Men’s Society

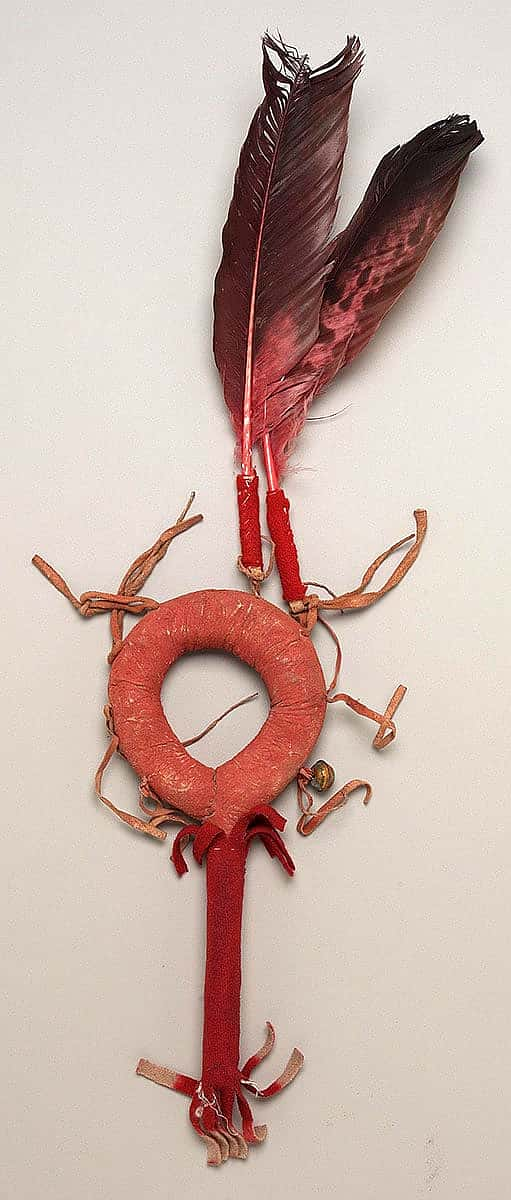

The two sides of the Tomahawk Lodge opposed each other in songs and telling war stories…. The paraphernalia needed for this lodge were the war club, white crane feathers, a calf tail, white and black paint. —Jessie Rowledge, Hinono’ei (Southern Arapaho)

Men gained respect, honor, and responsibility through membership in warrior societies. In Arapaho and other “age-graded” societies, members moved through the men’s societies in successive steps at prescribed ages.

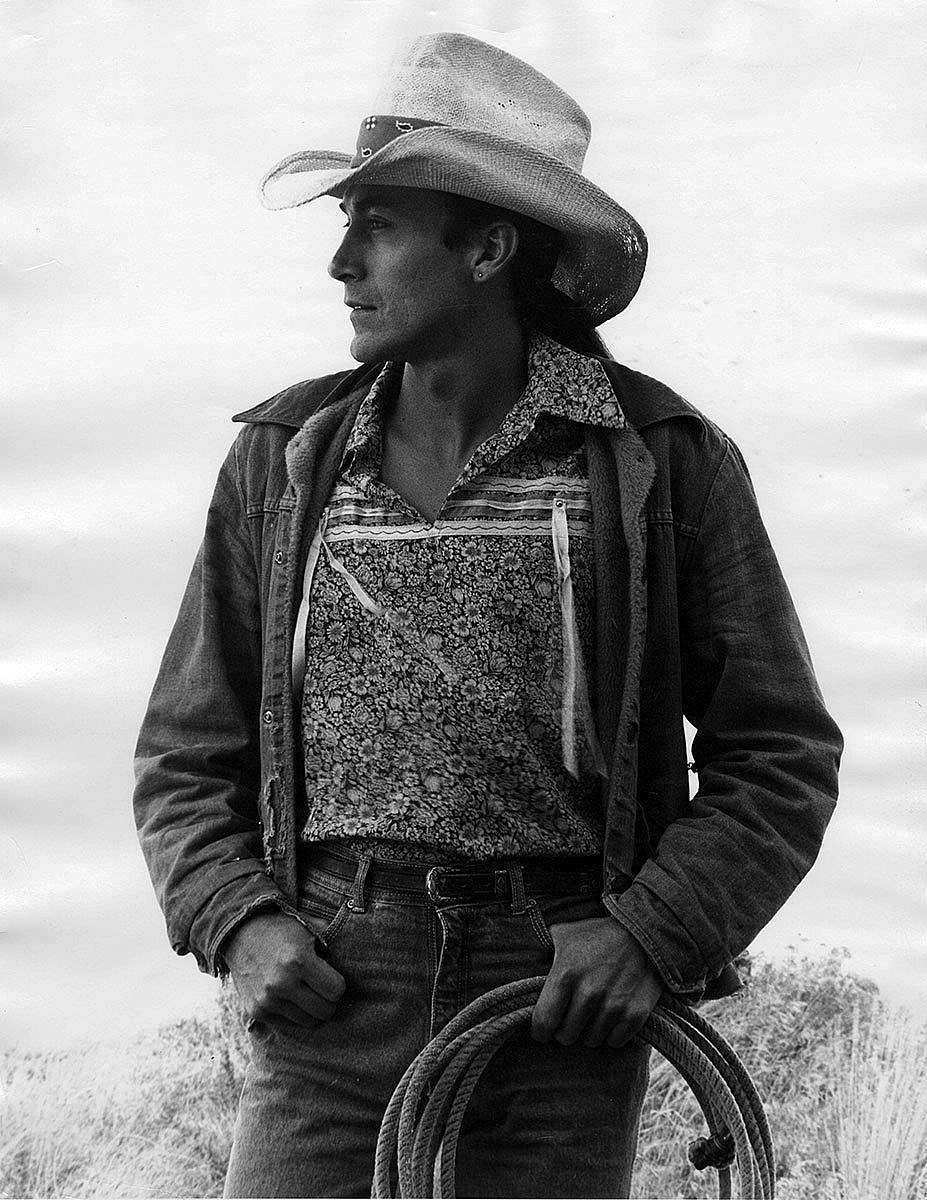

Adult: Warriors

The Northern Arapaho had a strong warrior society…. I earned my eagle feathers while I was there and I’m very proud to have served there…. I’ve come home to my people. And like I went over to fight for the United States…now I’m back home fighting for my people. —Eugene Goggles, Hinono’ei (Arapaho), 1990

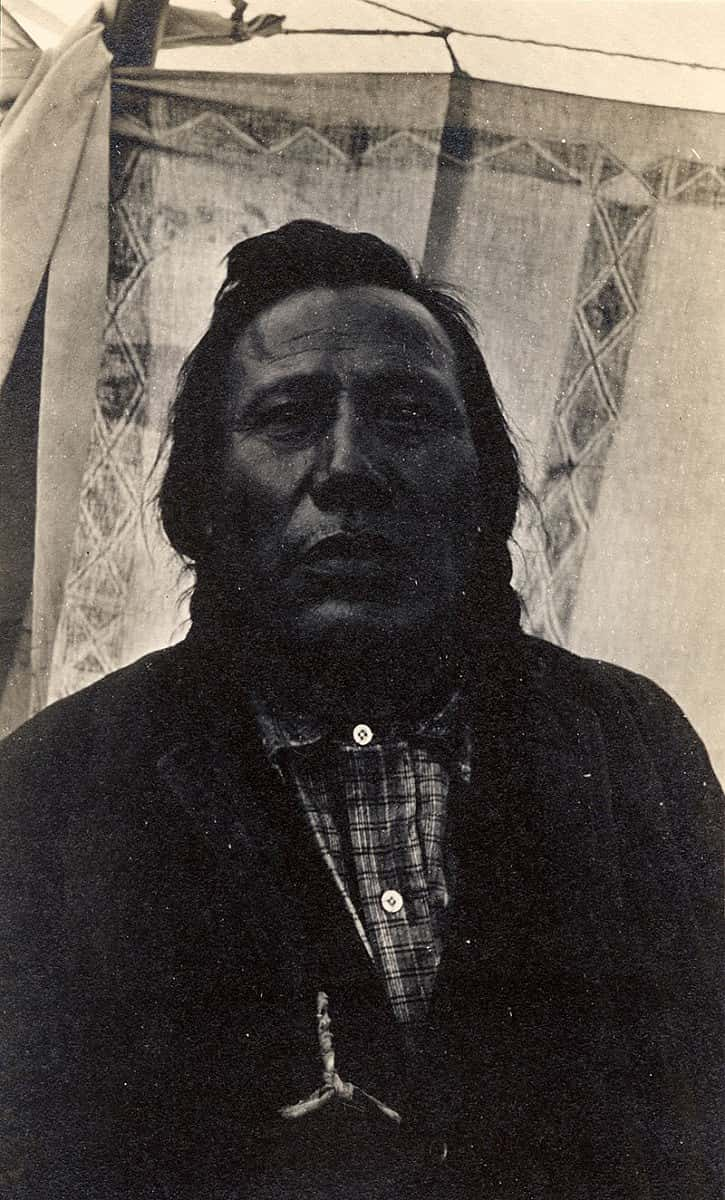

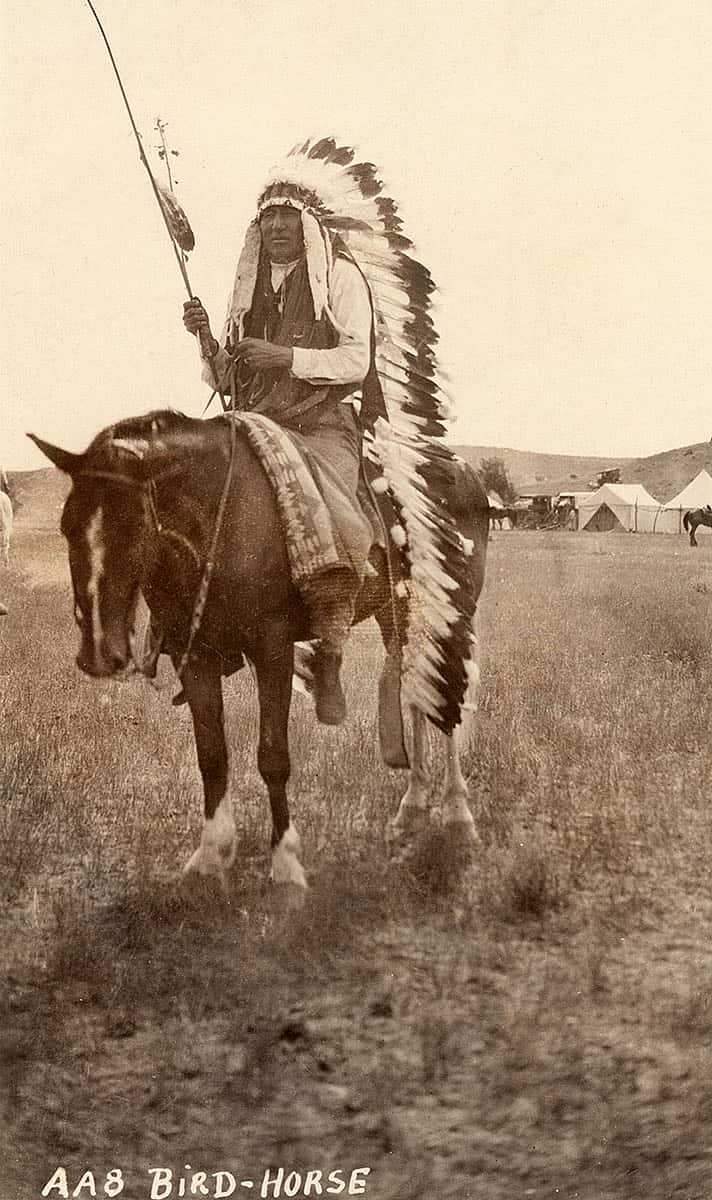

Adult: Leadership

…I told my grandchildren, I said, ‘Now one of you has to be leaders,’ I said, ‘Your grandfather was one of them…he was a leader, Chief Black Coal… So one of you have to live up to that…tradition. —Cleone Thunder, Hinono’ei (Arapaho), 1998

Black Coal, Hinono’ei (Northern Arapaho) resisted federal government attempts to remove his people to Oklahoma. In 1878, as the tribe was settled on the Wind River Reservation, he became one of the early council chiefs and a spokesman for the tribe.

I thought long and hard about it for a number of years before I got on a council. It was a willingness to serve. A willingness to try to make a difference, to contribute…. You’re there for other people. —Ivan Posey, So-soreh (Eastern Shoshone), 1998

When you want to teach tradition, values, and all this other stuff, there’s this umbrella. And I think respect is the umbrella, because all these other things will out from it. If you’ve got respect for yourself; respect for others; respect for Mother Earth; respect for tradition, culture, religion, whatever, I think you’re going to do good in life. If you just have that basic respect…the umbrella of respect.

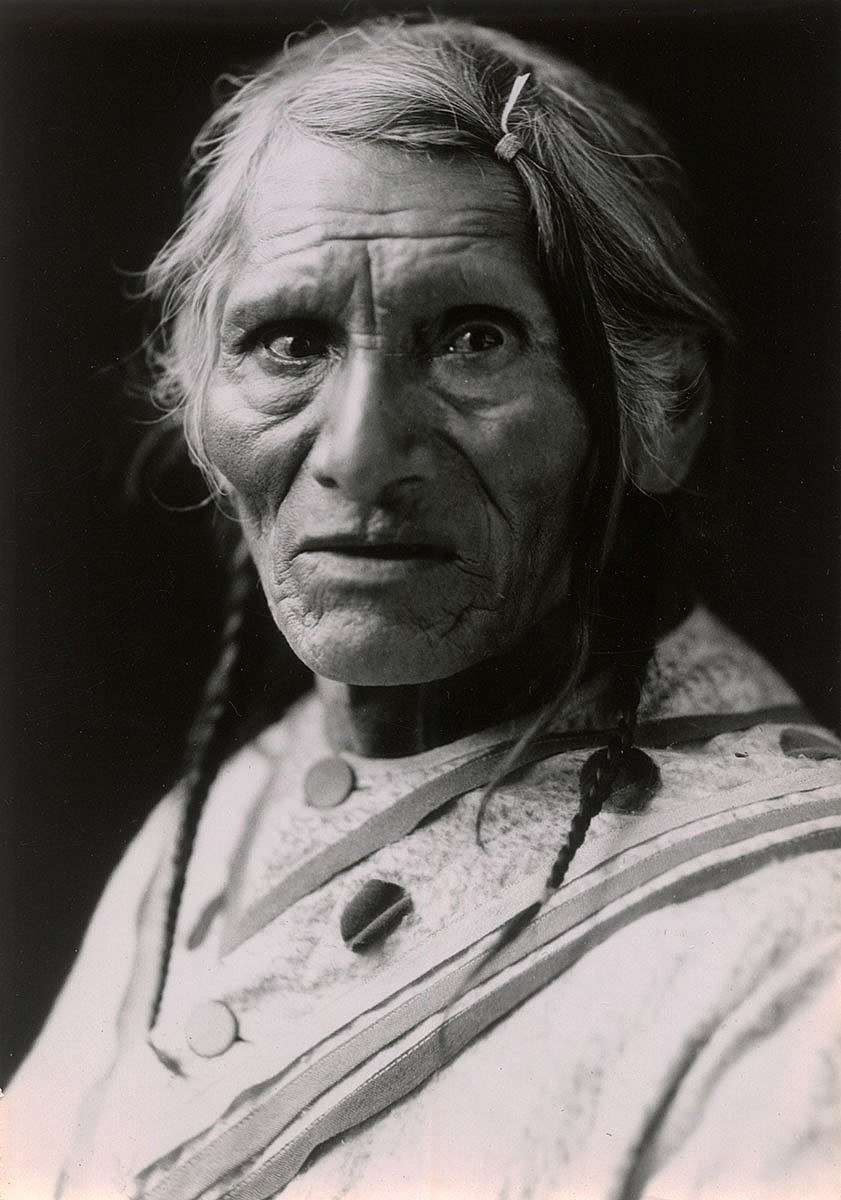

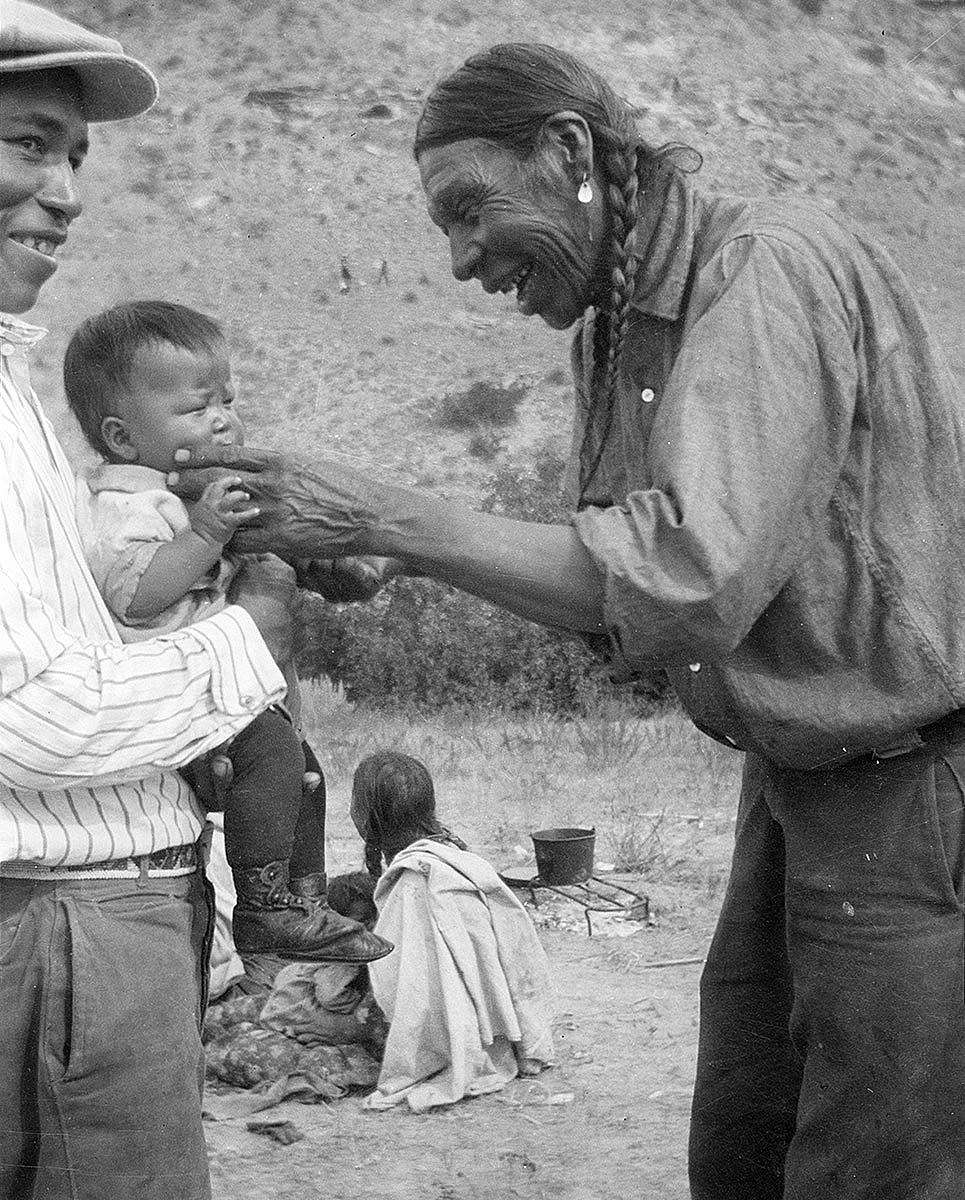

Elder

Plains people consider age a blessing. Elders provide a vital link with the past. They pass on knowledge to the next generations. They are the authorities in religion, culture, and social values.

Elder: Sacred Knowledge

The buffalo sang to us so that we would grow strong. And the Old People would gather together many words to make prayers to the creator. They would gather words as they walked the sacred path across the Earth, leaving nothing behind but prayers and offerings. —Debra Calling Thunder, Hinono’ei (Northern Arapaho), 1993

Elders are guardians of sacred knowledge, objects, and ceremonial traditions, serving as intermediaries between the Creator and the people.

Among the Arapaho, seven old men, known as the Water Pourers, protected the sacred bundles. They fasted and prayed together in a sweat lodge, pouring water over the hot rocks to make steam.

Women elders also were keepers of sacred knowledge and objects. They supervised arts that women undertook—tipi ornaments, buffalo robes, and cradles. Today, men and women elders continue to advise in sacred and other matters and are respected in their roles.

Elder: Age is a Blessing

For most people of the Plains, aging is seen as a supernatural blessing and a sign of social accomplishment, to be welcomed, not feared. Special ceremonies and celebrations mark milestones along the path of life from birth to death, and into the afterlife.

Generosity is a way to gain honor. Giveaways accompany important rituals throughout life, from a baby’s first steps to a loved one’s memorial. During giveaways, family members publicly distribute property—a horse, food, blankets, or handmade quilts—in honor of a relative, to express appreciation, or to acknowledge acceptance of a responsibility.

Honor dances are held during powwows and other public gatherings. Memorials honor the memory and celebrate the life of a respected tribal member.

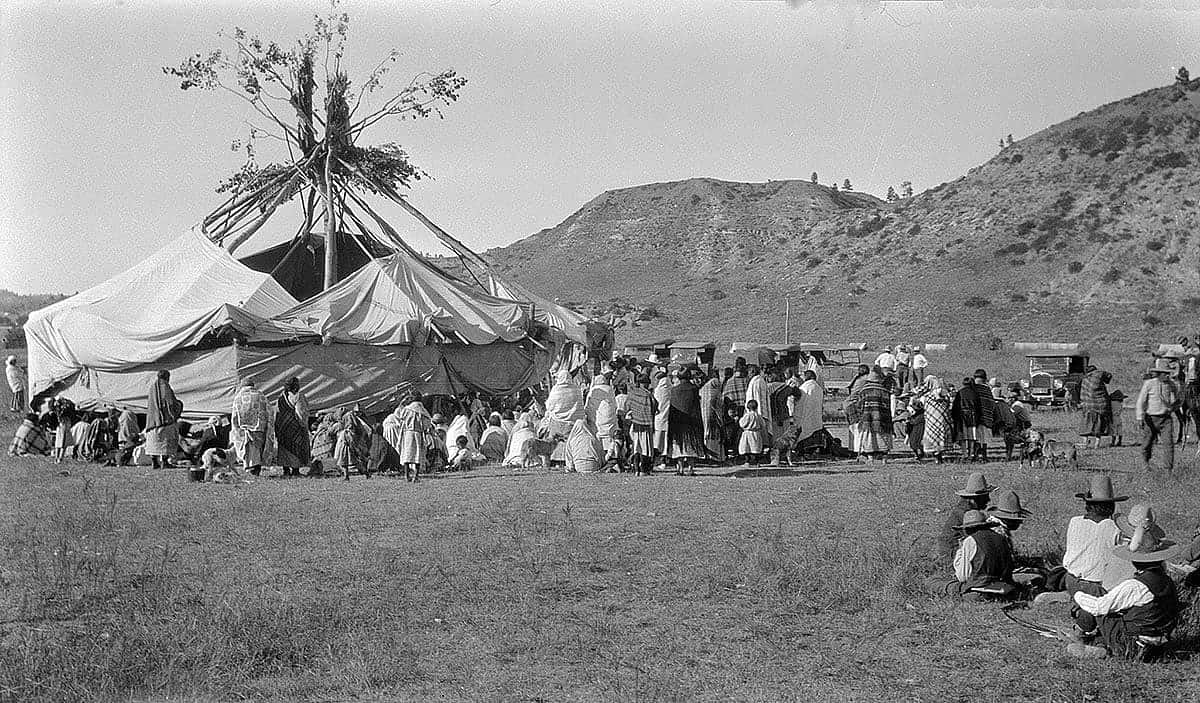

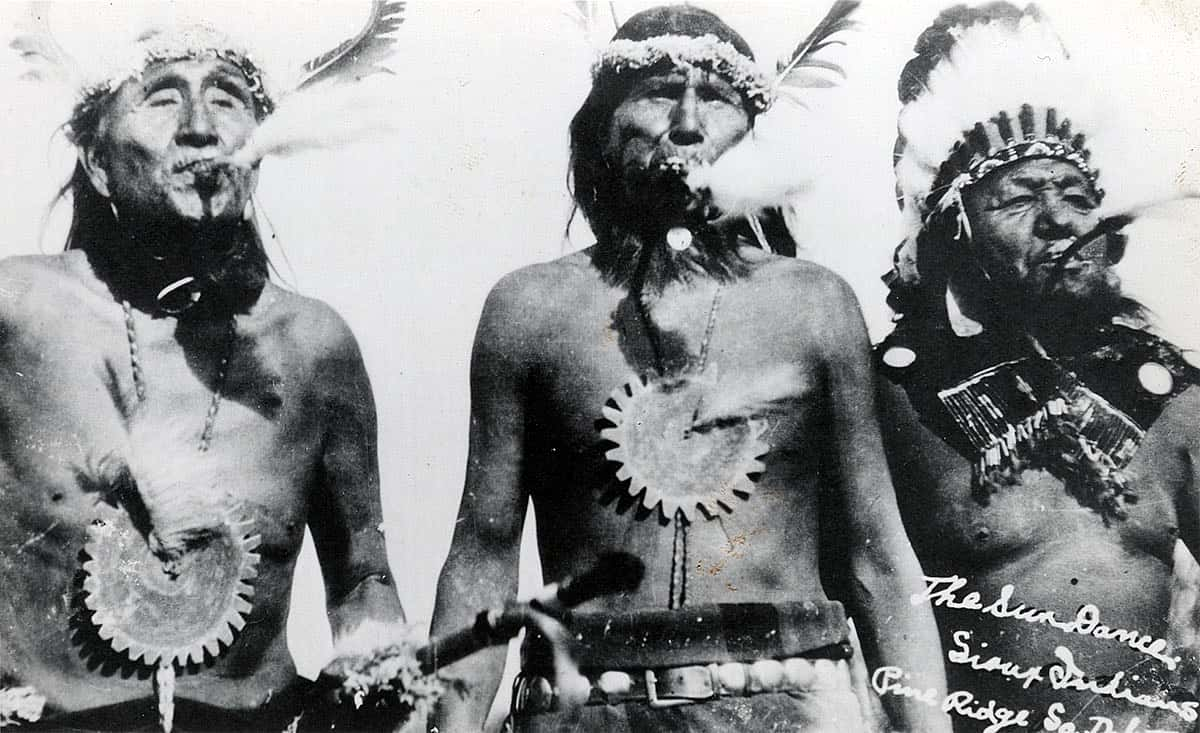

Elder: Sun Dance

He was sitting on a hill when he saw a buffalo coming up way down from the bottom of that hill. That buffalo seemed strange to him because he had yellow paint on…. And he’d walk so far and he’d take up dirt and he’d throw it up like this, like he’s mad. Throw it on himself and he’d walk, and he knew where that man was too; probably sent by the Great Spirit…. So the buffalo talked to him and told him about the Sun Dance—and told him about everything, how to put up the dance hollow, and songs, and all that, told him all about it…. He told him to go back and put up a Sun Dance for the people. So he did. —Starr Weed, So-soreh (Shoshone), 1998

The annual Sun Dance, the most important ceremony in the religious life of many Plains tribes, brings together “all the lodges” or ceremonial divisions of society. Elders serve as guardians of objects and ceremonies which are so sacred that no one speaks of them outside the specially-built Sun Dance lodge.

Today, the Sun Dance is observed by many Plains tribes—the Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, Arapaho, Crow, and Shoshone. The three or four day gathering, traditionally about purification and renewal, also serves as a reunion for tribal and family members.

Elder: Grandparents

Sometimes I get up in the morning and sing to my great grandson, he’s just a little baby, about six months old. I sing these warrior songs to him, and round dance, powwow dance songs. And some family songs I sing to him…. That’s how I want that little boy to maybe bank it up in his mind, maybe some day that he’s going to sing it, maybe he’s going to sing it to some younger people too as he’s growing up. That’s where I learned those songs. So anyway, I’d like for my great grandson to learn all these old songs. —Tony Engavo, So-soreh (Shoshone), 1998

If a young person wants to know something, go up to ask some elder a question. There’s no shame of asking, because if this person knows, they’re going to tell them how it is. And if he don’t, why, he’s going to send him to another one. That’s how they learn. They go to elders like that and find out things, and that’s how they learn. —Tony Engavo, So-soreh (Shoshone), 1998

More than just grandparents, the elderly are the strength and foundation of Indian cultures. They are our password to a meaningful life and to the wisdom and beauty of old age. —Abraham Spotted Elk, Tsistsistas (Northern Cheyenne), 1994

Continue to Adversity and Renewal…

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.