Blacks in Army Blue – Points West Online

Originally published in Points West magazine

Fall/Winter 2018

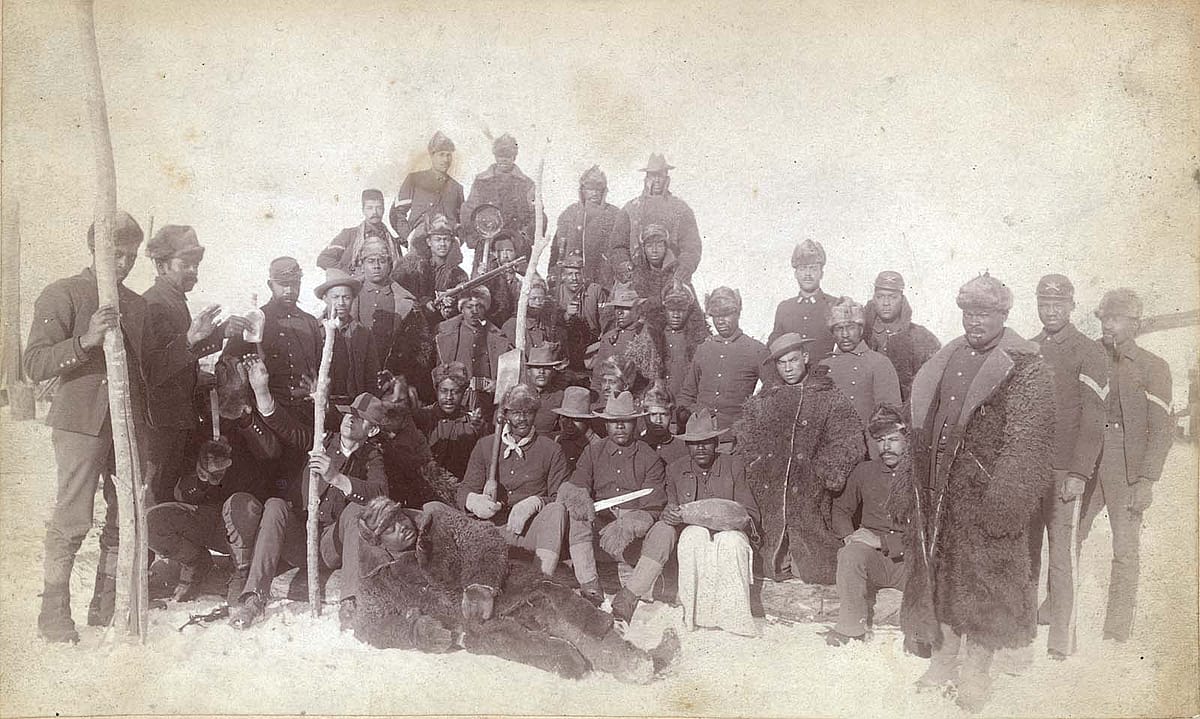

Blacks in Army Blue: Early Depictions by Frederic Remington and William F. Cody

By Dr. John Langellier

John Langellier knows a thing or two about military history: He has a doctorate in the subject and spent twelve years in the United States Army. In his research on buffalo soldiers, he discovered that contemporaries William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody and artist Frederic Remington both had specific connections to this band of soldiers…and each to his beloved American West.

Sketching the Buffalo Soldiers

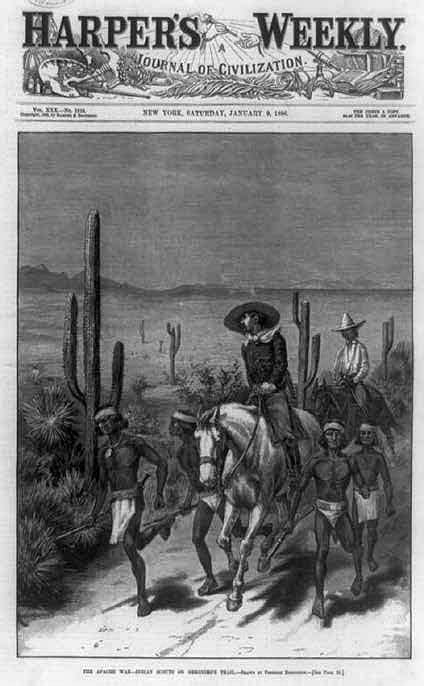

Writing as a cadet from Highland Military Academy in Worcester, Massachusetts, young Frederic Remington revealed to a pen pal that while images of “Indians, cowboys, villains, and toughs” thrilled him, his favorites were “soldiers.” Appropriately, the first published image bearing the artist’s signature appeared in the January 9, 1886, edition of the popular Harper’s Weekly over the caption “Apache War—Indian Scouts on Geronimo’s Trail.” With that modest effort, Remington commenced his rapid rise in western art. It all began during 1886 while following the bugle along Arizona’s border with Mexico.

Remington was raised on stories of his Union cavalryman father. Then, with the death of the family’s head, Fred abandoned playing college football at Yale to try his hand at raising sheep in Kansas. This rather unorthodox endeavor did one thing: With funds from subsequently selling his spread in 1884, the transplanted Easterner set out on a path that would change his world. In the process, the artist carved out his place alongside a select cadre of others who shaped the West of legends.

Remington’s grubstake allowed him to head to the Southwest to try his hand at art. So it was that this Eastern dude packed his paints, brushes, pens, camera, and other supplies, along with a small volume of blank pages that became his journal of a trip across the continent through Arizona and Sonora Old Mexico.

The stout greenhorn had gained a golden opportunity to experience a whole new world first hand and portray it under his own name. He filled his pocket journal with brief, memory-jogging notes such as a passing reference where he simply noted a “batch of negro cavalrymen” traveling westward by train. He pronounced them “good style men.”

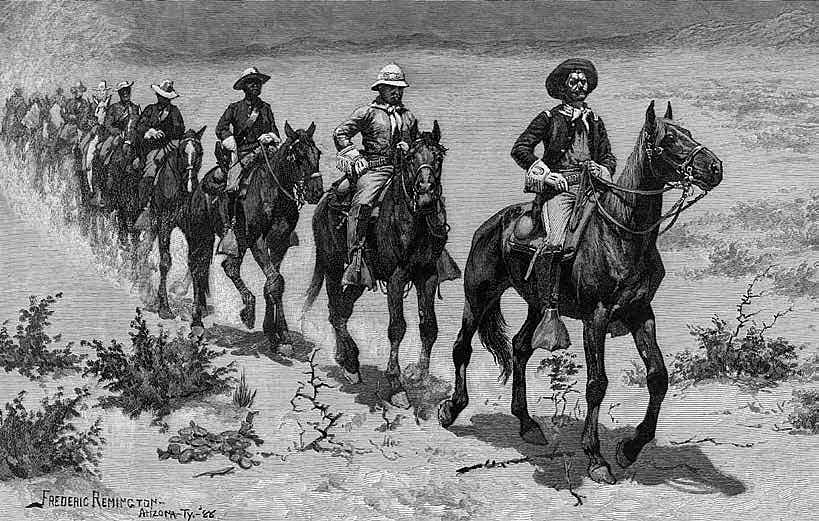

Embedding with the Tenth

By June 10, 1886, the novice roving reporter-illustrator would have the opportunity to take a closer look at these African-American horse soldiers, writing once more in his journal, “Got up late after a good night rest at Palace Hotel [Tucson], took camera went to the detachment of 10th Colored Cavalry—took a whole set of photographs.” Second Lieutenant Powhatan Clarke, the white commanding officer of the detachment, instructed Troop K’s First Sergeant William H. Givens “to do anything that Remington required.”

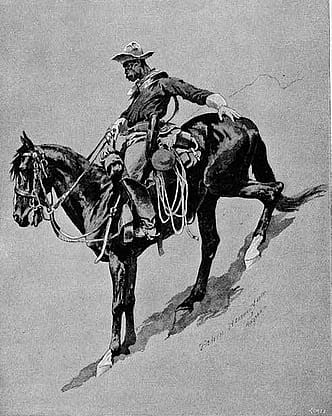

Born in Kentucky, Givens had enlisted in 1869 as a private in the Tenth. He rose through the ranks to First Sergeant, served on the border against the Apache chief Victorio, and demonstrated administrative capabilities that eventually led to his taking examinations for various non-commissioned staff positions. Remington could not have asked for a better introduction to the men of the Tenth; in Givens, he now had the top soldier at his disposal. When he asked for “a horse” to be “saddled by the dilletanters [sic] of army regulations,” Givens saw to it that one of his troopers carried out the request. This allowed Remington to produce an accurate image of the equine field pack. Accordingly, he began to sketch, surrounded by an audience of Mexican and black soldiers who looked on intently. In his journal, the artist made a note about a possible title for the picture. Would it be “saddle up”?

Some have argued that Remington’s emergence as “one of the most celebrated American-born artists can be traced to his first rough renderings of black soldiers in Arizona Territory…” As proof, between 1886 and 1897, Remington created nearly 2,300 works of art—270 of which represented the frontier army with some fifty or more portraying black soldiers. Before Remington set his sights on the subject, only two known post-Civil War depictions of African American soldiers in the West had been published. Consequently, Remington’s numerous images, coupled with his own quickly growing prominence, were influential in making the reading public aware of their presence. In the process, perhaps Remington became the father of the buffalo soldier legend as it has come down to us today.

Meanwhile

Even as these black soldiers played a part in Remington’s ascent to fame, William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody was well along in reinventing himself from a frontier scout into a famous showman. With the creation of his storied Buffalo Bill’s Wild West just a few years before Remington’s travels to the Southwest, he squarely rode in the front ranks of western legend makers. Unlike Remington, who observed history, Cody made history.

Drawing on his own past, Cody staged action-packed shows that took some lessons from the circus, but went far beyond with elements of rodeo, spectacle, drama, and much more. His unique blend thrilled audiences in North America and Europe who flocked by the thousands to relive those exciting “days of yesteryear”—at least according to Cody’s take on those bygone times.

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West evolved as the canny entertainer and educator strove to keep the program fresh, timely and offer a degree of authenticity. Somewhat by serendipity, as the May 13, 1894, edition of the New York World reported, the United States Army lent Cody “a double troop of United States Cavalry from the famous Ninth Regiment Fort Riley. As this was a genuine showing of regular soldiers, the interest in it was unbounded….” During that summer, both buffalo soldiers of the Ninth and white troopers from the Seventh delighted Cody’s crowds with their amazing equestrian skills.

Cody was no stranger to black cavalrymen. During 1868, he briefly hunted and scouted for Troop I, Tenth U.S. Cavalry under Captain George Armes. In his Ups and Downs of an Army Officer, this sometimes cantankerous—but always ready for action—officer recorded “Buffalo Bill,” (as he had been dubbed by this time) as “one of our scouts and one of the best shots on the plains…. He gets $60 per month and a splendid mule to ride, and is one of the most contented and happy men I ever met.”

Consequently, with many factors in play, Cody added African Americans to his Congress of Rough Riders of the World—albeit not as active duty enlisted men. Instead, the troops would be portrayed by veterans from the four black regiments. Indeed, by 1899, when Cody added a large-scale recreation of the Battle of San Juan Hill to the Wild West, the cast included representations of the Twenty-fourth U.S. Infantry along with the Ninth and Tenth U.S. Cavalry regiments. The following year, Cody continued the epic mock fight replete with Gatling guns and a make-believe Theodore Roosevelt storming the Spanish bastions. The simulated battle continued as part of the Wild West from 1902 through 1904. In fact, during several seasons, African American cast members represented buffalo soldiers as part of the heroic American and Cuban force, winning the day at a recreated San Juan assault and thereby reflecting historical fact.

Even three dime novels (among the scores of these inexpensive escapist pulps with the character of Cody as the hero) featured “The Tenth Cavalry of Colored Troops.” In one of these fanciful adventures, published in 1901 as the first known fictional portrayal of black frontier troops, “Buffalo Bill, appointed for a special purpose, Chief of Scouts of the Tenth United States Cavalry, a regiment of black troopers, was off on one of his lone and daring trails….”

To perform his mission, Cody enlists a few dozen soldiers whom he believes would “make good scouts…” The fictional stand-in for Buffalo Bill tells one of the officers, “While the Indians are as scared of the black soldiers as the latter are of them—they just don’t understand their being black and call them ‘Heap Black Paleface Braves.'”

Indeed, the trio of stories, while using some dialect, favorably depicts Cody’s African American recruits, particularly Sergeant Mobile Buck. In some ways, this positive brave black character foreshadows images of NCOs (noncommissioned officers) found in later novels, films, and television portrayals.

Regrettably, nearly three quarters of a century passed before authors, television producers, and filmmakers rediscovered frontier blacks who wore Army blue. When they finally did, they failed to realize that they only were following a trail blazed by Remington, Cody, and so many others.

Dr. Langellier’s article characterizes the nature of history where, in any given age, innumerable connections are linked by names, places, and circumstances—like Remington and Cody. And, thus is the nature of historians like Langellier—an observant lot, always on the lookout for ties that bind the past to the present.

Editor’s note: Russian short story writer Anton Chekhov wrote in his The Witch and Other Stories, “‘The past,’ he thought, ‘is linked with the present by an unbroken chain of events flowing one out of another.’ And it seemed to him that he had just seen both ends of that chain; that when he touched one end the other quivered.”

About the author

John P. Langellier, a 2018 Buffalo Bill Center of the West Resident Fellow, has written scores of articles and dozens of books including his most recent titles, Fighting for Uncle Sam: Buffalo Soldiers in the Frontier Army and The “Trapdoor” Springfield: From the Little Bighorn to San Juan Hill. Growing up in Tucson, Arizona, Langellier spent four decades in public history after graduating from the University of San Diego, and then Kansas State University, where he earned a PhD in military history. He spent a dozen years with the U.S. Army, and then served tenures at Autry Museum of the American West, Wyoming State Museum, Ronald Reagan Presidential Library, Sharlot Hall Museum, and Arizona Historical Society’s Central Division.

Now retired, Langellier spends his time writing, consulting, and producing about the West including serving as film consultant to the 2010 PBS documentary, For Love of Liberty: The Story of America’s Black Patriots, hosted by Halle Berry.

Post 298

Written By

Nancy McClure

Nancy now does Grants & Foundations Relations for the Center of the West's Development Department, but was formerly the Content Producer for the Center's Public Relations Department, where her work included writing and updating website content, publicizing events, copy editing, working with images, and producing the e-newsletter Western Wire. Her current job is seeking and applying for funding from government grants and private foundations. In her spare time, Nancy enjoys photography, reading, flower gardening, and playing the flute.